Managing Northern Forests for Black Bears1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Forage Availability on Diet Choice and Body Condition in American Beavers (Castor Canadensis)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 2013 The oler of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud Northern Michigan University Steve K. Windels National Park Service Jerrold L. Belant Mississippi State University John G. Bruggink Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Severud, William J.; Windels, Steve K.; Belant, Jerrold L.; and Bruggink, John G., "The or le of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis)" (2013). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 124. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mammalian Biology 78 (2013) 87–93 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Mammalian Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mambio Original Investigation The role of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud a,∗, Steve K. Windels b, Jerrold L. Belant c, John G. Bruggink a a Northern Michigan University, Department of Biology, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette, MI 49855, USA b National Park Service, Voyageurs National Park, 360 Highway 11 East, International Falls, MN 56649, USA c Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA article info abstract Article history: Forage availability can affect body condition and reproduction in wildlife. -

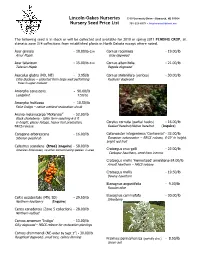

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

A Forever Green Agriculture Initiative

Developing High-efficiency Agricultural Systems: A Forever Green Agriculture Initiative Donald Wyse, University of Minnesota How did agricultural landscapes lose their diversity? Hansen, MN Exp Sta Protein efficiency 14% 1lb Pork 1,630 gal water 1lb Potatoes 24 gal water ETHANOL FROM CORN Dry Milling Process Grain Grind, Enzyme Digestion Distillers Grains Sugars Yeast, Distillation ETHANOL Conceptual framework for comparing land use and trade-offs of ecosystem services J. A. Foley et al., Science 309, 570 -574 (2005) Published by AAAS What are some of the consequences resulting from the loss of landscape diversity and continuous living soil covers? GGasper, USDA, NRCS Hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico 30.0 L. Calcasieu Atchafalaya R. Sabine L. Mississippi R. 29.5 Terrebonne Bay 29.0 latitude (deg.) 28.5 50 km 93.5 92.5 91.5 90.5 89.5 longitude (deg.) bottom dissolved oxygen less than 2.0 mg/L, July 1999 Rabalais et al. 2000 Satellite images of vegetative activity. Areas of annual row cropping April 20 – May 3 Areas of perennial vegetation May 4 – 17 Satellite images of vegetative activity. May 18 - 31 June 15 - 28 Satellite images of vegetative activity. July 13 - 26 October 5 - 18 Annual Tile Drainage Loss in Corn-Soybean Rotation Waseca, 1987-2001 July-March April, May, 29% June 71% Gyles Randall, 2003 Nitrogen Loads long-term average million lbs per year Statewide nitrogen sources to surface waters Urban Septic Feedlot runoff Stormwater 2% <1% 1% Forests 7% Atmospheric Cropland 9% groundwater Point 30% sources 9% Cropland runoff Cropland tile 5% drainage 37% Long Term Nitrogen Reductions 40% Veg. -

Native Trees of Massachusetts

Native Trees of Massachusetts Common Name Latin Name Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus Common Name Latin Name Mountain Pine Pinus mugo Pin Oak Quercus palustris Pitch Pine Pinus rigida White Oak Quercus alba Red Pine Pinus resinosa Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris Chestnut Oak Quercus montana Jack Pine Pinus banksiana Eastern Cottonwood Populus deltoides Eastern Hemlock Tsuga canadensis https://plants.usda.gov/ Tamarack Larix laricina core/profile?symbol=P Black Spruce Picea mariana ODE3 White Spruce Picea glauca black willow Salix nigra Red Spruce Picea rubens Red Mulberry Morus rubra Norway Spruce Picea abies American Plum Prunus americana Northern White cedar Thuja occidentalis Canada Plum Prunus nigra Eastern Juniper Juniperus virginiana Black Cherry Prunus serotina Balsam Fir Abies balsamea Canadian Amelanchier canadensis American Sycamore Platanus occidentalis Serviceberry or Witchhazel Hamamelis virginiana Shadbush Honey Locust Gleditsia triacanthos American Mountain Sorbus americana Eastern Redbud Cercis canadensis Ash Yellow-Wood Cladrastis kentukea American Elm Ulmus americana Gray Birch Betula populifolia Slippery Elm Ulmus rubra Grey Alder Alnus incana Basswood Tilia americana Sweet Birch Betula lenta Smooth Sumac Rhus glabra Yellow Birch Betula alleghaniensis Red Maple Acer rubrum Heartleaf Paper Birch Betula cordifolia Horse-Chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum River Birch Betula nigra Staghorn Sumac Rhus typhina Smooth Alder Alnus serrulata Silver Maple Acer saccharinum American Ostrya virginiana Sugar Maple Acer saccharum Hophornbeam Boxelder Acer negundo American Hornbeam Carpinus caroliniana Black Tupelo Nyssa sylvatica Green Alder Alnus viridis Flowering Dogwood Cornus florida Beaked Hazelnut Corylus cornuta Northern Catalpa Catalpa speciosa American Beech Fagus grandifolia Black Ash Fraxinus nigra Black Oak Quercus velutina Devil's Walkingstick Aralia spinosa Downy Hawthorn Crataegus mollis. -

Short-Term Fate of Rehabilitated Orphan Black Bears Released in New Hampshire

Human–Wildlife Interactions 10(2): 258–267, Fall 2016 Short-term fate of rehabilitated orphan black bears released in New Hampshire Wˎ˜˕ˎˢ E. S˖˒˝ˑ1, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, 56 College Road, Durham, NH 03824, USA [email protected] Pˎ˝ˎ˛ J. Pˎ˔˒˗˜, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, 56 College Road, Durham, NH 03824, USA A˗ˍ˛ˎˠ A. T˒˖˖˒˗˜, New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, 629B Main Street, Lancaster, NH 03584, USA Bˎ˗˓ˊ˖˒˗ K˒˕ˑˊ˖, P.O. Box 37, Lyme, NH 03768, USA Abstract: We evaluated the release of rehabilitated, orphan black bears (Ursus americanus) in northern New Hampshire. Eleven bears (9 males, 2 females; 40–45 kg) were outfi tted with GPS radio-collars and released during May and June of 2011 and 2012. Bears released in 2011 had higher apparent survival and were not observed or reported in any nuisance behavior, whereas no bears released in 2012 survived, and all were involved in minor nuisance behavior. Analysis of GPS locations indicated that bears in 2011 had access to and used abundant natural forages or habitat. Conversely, abundance of soft and hard mast was lower in 2012, suggesting that nuisance behavior, and consequently survival, was inversely related to availability of natural forage. Dispersal from the release site ranged from 3.4–73 km across both years, and no bear returned to the rehabilitation facility (117 km distance). Rehabilitation appears to be a valid method for addressing certain orphan bear issues in New Hampshire. -

We Hope You Find This Field Guide a Useful Tool in Identifying Native Shrubs in Southwestern Oregon

We hope you find this field guide a useful tool in identifying native shrubs in southwestern Oregon. 2 This guide was conceived by the “Shrub Club:” Jan Walker, Jack Walker, Kathie Miller, Howard Wagner and Don Billings, Josephine County Small Woodlands Association, Max Bennett, OSU Extension Service, and Brad Carlson, Middle Rogue Watershed Council. Photos: Text: Jan Walker Max Bennett Max Bennett Jan Walker Financial support for this guide was contributed by: • Josephine County Small • Silver Springs Nursery Woodlands Association • Illinois Valley Soil & Water • Middle Rogue Watershed Council Conservation District • Althouse Nursery • OSU Extension Service • Plant Oregon • Forest Farm Nursery Acknowledgements Helpful technical reviews were provided by Chris Pearce and Molly Sullivan, The Nature Conservancy; Bev Moore, Middle Rogue Watershed Council; Kristi Mergenthaler and Rachel Showalter, Bureau of Land Management. The format of the guide was inspired by the OSU Extension Service publication Trees to Know in Oregon by E.C. Jensen and C.R. Ross. Illustrations of plant parts on pages 6-7 are from Trees to Know in Oregon (used by permission). All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Book formatted & designed by: Flying Toad Graphics, Grants Pass, Oregon, 2007 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 4 Plant parts ................................................................................... 6 How to use the dichotomous keys ........................................... -

Oberlin's Experimental Hazelnut Orchard: Exploring Woody Agriculture’S Potential for Climate Change Mitigation and Food System Resilience

Oberlin's Experimental Hazelnut Orchard: Exploring Woody Agriculture’s Potential for Climate Change Mitigation and Food System Resilience By: Naomi Fireman Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 3 1.1 Contextualizing the issue 3 1.2 Woody agriculture as a solution 5 1.3 Hazelnuts, Hybrid Hazelnuts, and Neohybrid Hazelnuts 9 Chapter 2: Biological Background, Fertilization, and Soils 11 Chapter 3: Methods 17 3.1 System Description 17 Management 18 3.2 Initial site conditions, preparation, and planting of trees 18 3.3 Current conditions 19 3.4 Independent and dependent variables 20 3.5 General tree care 20 Data Collection 21 3.6a Harvesting nut/husk clusters 21 3.6b Determining nut and husk biomass 22 3.7a Estimating biomass of woody stems 22 3.7c Developing allometric equations 25 3.8a Estimating leaf biomass 26 3.9 Measuring soil organic matter (SOM) 26 3.10 Statistical analysis 27 Chapter 4: Results 28 4.1 Analysis of covariance: effects of time and fertilizer treatment 28 4.1a Effects of time 28 4.1b Effects of fertilizer 29 4.1c Time and fertilizer treatment interaction 30 4.2 Correlations among variables 32 Chapter 5: Analysis & Discussion 33 5.1 Has the annual allocation of carbon to leaves, woody tissue, and nuts changed over time as the trees have matured? 33 5.2 How much carbon is being stored in the hazelnut system, where is it being stored, and how has this changed over time? 34 5.3 Is fertilization affecting patterns of carbon allocation and long-term storage? 35 5.4 Are these genetically diverse trees capable of producing -

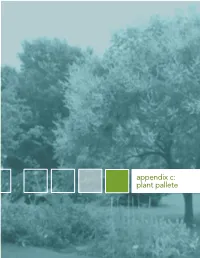

Appendix C: Plant Palette

appendix c: plant pallete plant palette The Plant Palette identifies shade, understory and small trees, shrubs, groundover, perennials and ornamental grasses appropriate for the projects identified within the Urban Greening Plan and consistent with the policy direction defined by the Urban Greening objectives. The Plants defined as part of this plant palette do not represent an exhaustive list of appropriate or approved plants; they were developed to identify context- sensitive plant recommendations for El Cerrito’s streets, parks, and open spaces. This palette may be used to provide plant guidance to private projects interested in achieving the benefits identified by this Plan. This Palette is a living document and may be updated over time to better reflect changing environmental conditions. If the Plant Palette and the City’s current Master Tree List are in conflict, the current Master Tree List will take precedence. SHADE TREES Edible Native Evergreen Evergreen Water Use Water Litter Type Pollinators Deciduous/ Root Damage Landscape Use Creek Interpret Creek Drought Tolerant Drought Desirable Wildlife Biofiltration Planter Scientific Name Common Name Biogenic Emissions Acer macrophyllum Big Leaf Maple ü ü ü ü D M Riparian M High Dry Alnus rhombifolia White Alder ü ü D H Riparian ü High Dry Alnus rubra* Red Alder ü D H Riparian - ü High Dry Betula jaquemontii Birch D H Riparian - ü Mod Dry Screen, Carpinus betulus 'Fastigiata' Fastigiate Hornbeam D M Hedged Low Dry Castanea sativa European Chestnut ü D - - Low Dry Screen, Geijera parvifolia -

G/SPS/N/KOR/98/Add.16 8 October 2007 ORGANIZATION (07-4279) Committee on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Original: English

WORLD TRADE G/SPS/N/KOR/98/Add.16 8 October 2007 ORGANIZATION (07-4279) Committee on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Original: English NOTIFICATION Addendum The following communication, received on 2 October 2007, is being circulated at the request of the Delegation of the Republic of Korea. _______________ Phytosanitary Measures to Prevent the Introduction of Sudden Oak Death Disease The National Plant Quarantine Service (NPQS), Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry in the Republic of Korea, has modified the "Tentative phytosanitary measures to prevent the introduction of Sudden Oak Death (SOD) Disease". This measure is applied to any propagative materials such as nursery stocks (including roots stock), cuttings and scions (except seeds and fruits), and woods (including logs) with bark of host or associated plants. Add the following plants to the associated plants: Garry elliptica Mahonia aquifolium For the importation of these new associated plants from the prohibited areas and these new associated plants from the regulated areas, phytosanitary certificates with the following additional declaration will be required for consignments shipped on or after 1 November 2007: "The shipment was inspected and found free of Phytophthora ramorum". In case of the United States, the name of the State and County are required on the Phytosanitary Certificate as additional information. G/SPS/N/KOR/98/Add.16 Page 2 Attachment List of Plants and Areas Related with Sudden Oak Death 1. Plants Any propagative materials such as nursery stocks (including -

List of Crop Plants Pollinated by Bees 1 List of Crop Plants Pollinated by Bees

List of crop plants pollinated by bees 1 List of crop plants pollinated by bees Pollination by insects is called entomophily. Entomophily is a form of pollination whereby pollen is distributed by insects, particularly bees, Lepidoptera (e.g. butterflies and moths), flies and beetles. Note that honey bees will pollinate many plant species that are not native to areas where honey bees occur, and are often inefficient pollinators of such plants. Please note that plants that require insect pollination to produce seeds do not necessarily require pollination to grow from seed into food. The carrot is an example. Common name Latin name Pollinator Commercial Pollinator number Geography product impact of of of pollination honey cultivation bee hives per acre Okra Abelmoschus Honey bees (incl. Apis cerana), fruit 2-modest temperate esculentus Solitary bees (Halictus spp.) Kiwifruit Actinidia deliciosa Honey bees, Bumblebees, Solitary fruit 4-essential bees Bucket orchid Coryanthes Male Euglossini bees (Orchid bees) Onion Allium cepa Honey bees, Solitary bees seed temperate Cashew Anacardium Honey bees, Stingless bees, nut 3-great tropical occidentale bumblebees, Solitary bees (Centris tarsata), Butterflies, flies, hummingbirds Atemoya, Annona squamosa Nitidulid beetles fruit 4-essential tropical Cherimoya, Custard apple Celery Apium graveolens Honey bees, Solitary bees, flies seed temperate Strawberry tree Arbutus unedo Honey bees, bumblebees fruit 2-modest American Pawpaw Asimina triloba Carrion flies, Dung flies fruit 4-essential temperate Carambola, -

Corylus Americana, American Hazelnut

Of interest this week at Beal... American Hazelnut Corylus americana Family: the Birch family, Betulaceae Also called American filbert W. J. Beal This nut-bearing member of the birch family is not as well known as its commercial Botanical Garden European counterpart, Corylus avellana. Ours are located on the hill overlooking the north side of the pond. Just as the European filbert has a long history of use in Europe, the American hazelnut has a long history of being harvested for food by the Indigenous First Nations peoples of Eastern North America. The fruit of the American hazelnut is comparable to the fruit of the cultivated European hazelnut, except significantly smaller. American hazelnut ranges from Maine west to Saskatchewan, south to eastern Oklahoma, east to northern Florida. In Michigan, American hazelnut is common throughout the southerly counties of the Lower Peninsula, but at the approximate latitude of the town of Clare, it is replaced by the more northerly distribution of beaked hazelnut, Corylus cornuta. American hazelnut flowers a few days after temperatures are consistently above 40 degrees. Male flowers are catkins that expand upon opening to release massive quantities of pollen. The unexpanded male catkins comprise one of its most recognizable winter features. Female flowers are striking but tiny sprays of bright red stigmata up to three millimeters in length. Flowers of both sexes are born on the same stems. American hazelnut forms thickets some 6-10 feet (2-3.3 m) in height especially along forest trails and edges. After pollination, the female flowers expand and wrap themselves in large frilly bracts that are the hallmark of their presence.