Thailand's Urbanized Villagers and Political Polarization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of AQ in Other Provinces Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | for More Information, Please Visit Note : 1

List of AQ Provinces As of 5 July 2021 List of AQ in other Provinces Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | For more information, please visit www.hsscovid.com Note : 1. Passengers arrived at Suvarnabhumi Airport/ Don Mueang International Airport can be quarantined in AQ located in Chonburi and Prachinburi. 2. Passengers arrived at Phuket International Airport can be quarantined in AQ located in Phuket and Phang-nga. 3. For travellers entering Thailand via Ban Klong Luek (Aranyaprathet) Border Checkpoint can be quarantined in AQ located in Prachinburi. 4. For travellers entering Thailand via 2nd Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge can be quarantined in AQ located in Mukdahan. How to make a reservation? - Contact a hotel directly for reservation - Make a reservation on authorized online platforms (1) https://entrythailand.go.th/ (2) https://asqthailand.com/ (3) https://asq.locanation.com/ (4) https://asq.ascendtravel.com/ (5) https://www.agoda.com/quarantineth Starting Price (per person) for Thais Price range (Baht) No. Hotel Name Partnered Hospital Total Room (with discount on RT-PCR-test) per person Chonburi 1 Best Bella Pattaya Hotel Banglamung Hospital 39,000 – 45,000 90 Family Packages are available. 2 Avani Pattaya Resort Bangkok Hospital Pattaya 71,000 – 105,000 232 Family Packages are available. 3 Hotel J Residence Vibharam Laemchabang 39,000 – 60,000 75 Hospital Family Packages are available. 4 Tropicana Pattaya Memorial Hospital 37,000 - 56,000 170 5 Grand Bella Hotel Banglamung Hospital 27,000 - 44,000 344 6 Bella Express Hotel Banglamung Hospital 26,000 166 7 Sunshine Garden Resort Vibharam Laemchabang 37,500 - 48,750 65 Hospital 8 The Green Park Resort Vibharam Laemchabang 39,750 - 48,750 113 Hospital 9 Ravindra Beach Resort and Spa Bangkok Hospital Pattaya 69,000 - 72,000 100 Family Packages are available. -

List of ASQ (Alternative State Quarantine) Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | for More Information, Please Visit Note : 1

As of 23 February 2021 List of ASQ (Alternative State Quarantine) Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | For more information, please visit www.hsscovid.com Note : 1. Passengers arrived at Suvarnabhumi Airport/ Don Mueang International Airport can be quarantined in ASQ and ALQ located in Chonburi and Prachinburi. 2. Passengers arrived at Phuket International Airport can be quarantined in ALQ located in Phuket and Phang-nga. 3. For travellers entering Thailand via Ban Klong Luek (Aranyaprathet) Border Checkpoint can be quarantined in ALQ located in Prachinburi. 4. For travellers entering Thailand via 2nd Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge can be quarantined in ALQ located in Mukdahan. How to make a reservation? - Contact a hotel directly for reservation - Make a reservation on authorized online platforms (1) https://www.agoda.com/quarantineth (2) https://asq.locanation.com/ (3) https://asq.ascendtravel.com/ Price range (Baht) Total No Name Partnered Hospital /person per 14-16 days Room 1 Movenpick BDMS Wellness Resort Bangkok Hospital 64,000 – 220,000 280 2 Qiu Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 32,000 – 35,000 105 3 The Idle Residence Samitivej Hospital 50,000 – 60,000 125 4 Grand Richmond Hotel World Medical Hospital (WMC) 45,000 - 90,000 300 5 Royal Benja Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 37,000 - 39,000 247 6 Anantara Siam Bangkok BPK 9 International Hospital 75,000 – 309,000 218 7 Grande Centerpoint Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 62,000 – 73,000 364 Sukhumvit 55 Family Packages are available. 8 AMARA Hotel Sukumvit Hospital 48,000 – 105,000 117 9 The Kinn Bangkok hotel Vibharam Hospital 30,000 – 50,000 61 Family Packages are available. -

Disaster Management Partners in Thailand

Cover image: “Thailand-3570B - Money flows like water..” by Dennis Jarvis is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/archer10/3696750357/in/set-72157620096094807 2 Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance Table of Contents Welcome - Note from the Director 8 About the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance 9 Disaster Management Reference Handbook Series Overview 10 Executive Summary 11 Country Overview 14 Culture 14 Demographics 15 Ethnic Makeup 15 Key Population Centers 17 Vulnerable Groups 18 Economics 20 Environment 21 Borders 21 Geography 21 Climate 23 Disaster Overview 28 Hazards 28 Natural 29 Infectious Disease 33 Endemic Conditions 33 Thailand Disaster Management Reference Handbook | 2015 3 Government Structure for Disaster Management 36 National 36 Laws, Policies, and Plans on Disaster Management 43 Government Capacity and Capability 51 Education Programs 52 Disaster Management Communications 54 Early Warning System 55 Military Role in Disaster Relief 57 Foreign Military Assistance 60 Foreign Assistance and International Partners 60 Foreign Assistance Logistics 61 Infrastructure 68 Airports 68 Seaports 71 Land Routes 72 Roads 72 Bridges 74 Railways 75 Schools 77 Communications 77 Utilities 77 Power 77 Water and Sanitation 80 4 Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance Health 84 Overview 84 Structure 85 Legal 86 Health system 86 Public Healthcare 87 Private Healthcare 87 Disaster Preparedness and Response 87 Hospitals 88 Challenges -

Gambling, the State and Society in Siam, C. 1880-1945

Gambling, the State and Society in Siam, c. 1880-1945 James Alastair Warren School of Oriental and African Studies A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of London 2007 ’ i ^ L’A 1 A ProQuest Number: 10672983 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672983 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 3 Abstract This study charts the evolution of government attitudes and policies towards gambling in Siam between the 1880s and 1945. Based on the assertion that gambling was a social evil that impoverished the population, encouraged crime, and retarded economic development, successive regimes sought to reduce and regulate the scope for legal gambling. This was expressed most concretely through a series of increasingly restrictive and punitive laws, which prohibited many popular forms of gambling and subjected others to strict licensing. Consequently, there was an increase in illegal gambling. In essence, gambling went from being a state acceptable activity to one that was criminal unless conducted within certain strict parameters. -

Integrated Solid Waste Management Plan: Buriram

TA-8566 REG: Mainstreaming Integrated Solid Waste Management in Asia Integrated Solid Waste Management Plan Buriram NovemberOctob 2015er 2016 Integrated SWM Plan Disclaimers This Integrated Solid Waste Management Plan shall not constitute the basis of any contract which may be concluded for the exchange of notes. The recipient must rely on its own enquiries and on the terms and conditions contained in any agreement, when and if finally executed, subject to such limitations or restrictions as may be specified therein. AECOM will devote normal professional efforts compatible with the time and budget available in performing the Services. AECOM's findings represent its reasonable judgments within the time and budget context of its commission and utilising the information available to it at the time of performing the Services. AECOM are making projections/recommendations based upon limited information that has been made available to them; such projections/recommendations are subject to many factors that are beyond the control of AECOM; and AECOM thus make no representations or warranties with respect to such projections/recommendations and disclaim any responsibility for the accuracy of any estimates, projections and recommendations. Any opinion expressed by AECOM concerning the revenue, capex and opex is based on the generally accepted engineering practice in effect at the time of the assignment and information that has been supplied to AECOM by the Client and others in connection with the assignment. Any indication of cost would be in the form of an ‘order of magnitude estimate’, which should only be considered as an early indication of cost and in no case be considered as the actual costs. -

Thailand's Inequality: Myths & Reality of Isan

1 THAILAND’S INEQUALITY: MYTHS & REALITY OF ISAN 2 3 THAILAND’S INEQUALITY: MYTHS & REALITY OF ISAN AUTHORS Rattana Lao omas I. Parks Charn Sangvirojkul Aram Lek-Uthai Atipong Pathanasethpong Pii Arporniem annaporn Takkhin Kroekkiat Tiamsai May 2019 Copyright © 2019 e Asia Foundation 4 5I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS is report on contemporary life in Isan, ailand’s Northeast Region, was produced with the support of a great many people. e study was co-funded by the United Kingdom and the Asia Foundation. e research team wishes to thank omas Parks, the Foundation’s Country Representative in ailand, for providing vision and encouragement through all stages of the study, including formulation of the methodology, analysis of the ndings, and drawing conclusions for this report. Important contributors during the early stages of the study were Sasiwan Chingchit, Patrick Barron, and Adrian Morel; and throughout the process, the Foundation’s sta in ailand provided crucial administrative and moral support. Most grateful thanks go to the farmers, students, and academics in Isan who participated in the survey, focus groups, and interviews, and generously provid- ed their time and valuable insights. We beneted too from the intellectual support of faculty at Khon Kaen University, Mahasarakam University, and Ubonratchathani University, and especially thank Dr. Rina Patramanon, Dr. Orathai Piayura, Dr. John Draper, Dr. Nattakarn Akarapongpisak, Dr. Titipol Phakdeewanich, and Dr. Preuk Taotawin. Dr. Atipong Pathanasethpong contributed his insight on the health section and oered critical understanding on Isan. Invaluable assistance was provided too by: William Klausner helped us to under- stand what Isan used to be and how it has changed; Sukit Sivanunsakul and Suphannada Lowhachai from the National Economic and Social Development Council and Dr. -

Bangkok & Phuket: Road to Recovery

Singapore: Hotel Market Market Report - March 2019 MARKET REPORT Bangkok & Phuket: Road to Recovery MAY 2021 Bangkok & Phuket: Road to Recovery Market Report - May 2021 Road to Recovery for Bangkok & Phuket Message to Readers The COVID-19 pandemic caught everyone by surprise. Nonetheless, as more and more destinations reopen for Without much preparation, the world succumbs to the business, competition will be intense and a price war seems highly contagious virus and its impact has been far-reaching inevitable. New projects postponed/mooted will gradually and long-lasting than any of the previous disasters. While make their way back to the market, adding more pressure. frontrunners like the United States and the United Kingdom Revenue per Available Room (RevPAR) measures of both have made advance progress on mass vaccination programs Bangkok and Phuket hotel markets are not anticipated to to curb the spread, uncertainties loom over subsequent fully return to the pre-COVID level by 2025. outbreaks as long as the majority of the world population is not immune to the disease. However, in every market, there are always winners and losers. Winners will by far outperform the market rebound. In a hard time like this, we feel the travel and tourism Meanwhile, losers will take much longer time to recover industry needs to stay current on the situation, make a fair and some may not survive the pandemic. assessment on positive and negative factors, and form an objective opinion on the market outlook. It is a crucial time to thoroughly diagnose your property’s health: What are unique selling points/competitive We hope our comprehensive study clearly presents advantages? How have they enabled the property to a market direction and recovery pace setting realistic compete? How is the property performing relative to the expectations and guiding business planning. -

Khmer Temples of Northeast Thailand: a Proposed Plan for Tourism Development

KHMER TEMPLES OF NORTHEAST THAILAND: A PROPOSED PLAN FOR TOURISM DEVELOPMENT Assist.Prof.Dr.Thirachaya Maneenetr Head of Tourism Department Faculty of Management Science, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand. [email protected] Abstract. This research is aimed at studing the Khmer temples of Northeast Thailand in order to propose a plan for tourism development. Seven Khmer temple sites were chosen, located in four provinces in the northeastern area of Thailand. These include Nakhon Ratchasima, Buriram, Surin and Si Sa Ket Provinces; and the temple sites of Prasat Phimai, Prasat Phanom Rung, Prasat Mueang Tam, Prasat Ta Muean Group, Prasat Si Khoraphum, Prasat Sa Kamphaeng Yai and Prasat Phra Wihan. From this study, the researcher attempted to use the concept of cultural tourism as a key in the conservation of the value and significance of the architectural heritage and cultural landscape of Khmer sites. The cultural tourism approach also attempts to take into account both tangible and intangible values surrounding the sites for sustainable tourism. The objective of the study is to promote the significance of Thailand’s Khmer sites with a view to improving accessibility for visitors. The aim is to provide the local community a well managed interpretation and conservation program for each important site and highlight their unique characteristics in a way that will help preserve them for future generations. A further aim of this study is to better present the Khmer sites of Northeast Thailand as part of a cultural panorama and to create a management plan for cultural tourism and sustainable tourism development. -

List of ALQ (Alternative Local Quarantine) Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | for More Information, Please Visit Note : 1

As of 6 November 2020 List of ALQ (Alternative Local Quarantine) Compiled by Department of Consular Affairs | For more information, please visit www.hsscovid.com Note : 1. Passengers arrived at Suvarnabhumi Airport/ Don Mueang International Airport can be quarantined in ASQ and ALQ located in Chonburi and Prachinburi. 2. Passengers arrived at Phuket International Airport can be quarantined in ALQ located in Phuket. 3. For travellers entering Thailand via Ban Klong Luek (Aranyaprathet) Border Checkpoint can be quarantined in ALQ located in Prachinburi. Price range (Baht) No. Hotel Name Partnered Hospital Total Room /person per 14-16 days Chonburi 1 Chonburi Best Bella Pattaya Hotel Banglamung Hospital 39,000 – 45,000 75 Family Packages are available. 2 Avani Pattaya Resort Bangkok Hospital Pattaya 65,000 – 127,000 92 Family Packages are available. 3 Hotel J Residence Bangkok Hospital Pattaya 44,000 – 60,000 75 Prachinburi 1 Tawa Ravadee Resort Chularat 304 International 57,000 96 Hospital Phuket 1 Anantara Mai Khao Phuket Bangkok Hospital Phuket 220,000 36 Family Packages are available. 2 Anantara Phuket Suites & Villas Bangkok Hospital Phuket 99,500 – 295,000 100 Family Packages are available. 3 Phuket GRACELAND Resort & Spa Bangkok Hospital Siriroj 82,000 – 95,000 343 Family Packages are available. 4 Metadee Resort & Villas Bangkok Hospital Siriroj 84,800 – 158,250 71 5 Banyan Tree Phuket Brochures are not available. Brochures are not available. 40 6 JW Mariott Hotels&Resort Bangkok Hospital Phuket 85,000 – 165,000 90 Family Packages are available. 7 Laguna Holiday Club Phuket Resort Brochures are not available. Brochures are not available. -

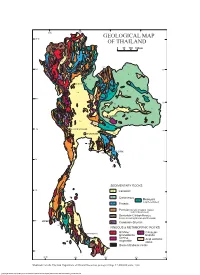

Geological Map of Thailand

° 98°E 100 ° g g GEOLOGICAL MAP 20 N V OF THAILAND g D-C D-C P g Mz 0 50 100 150km V Cz g Mz CHIANGMAI TR TR m P Cz g Cz g P D-C 18° 18° P C-S TR V P D-C g K D-C V Cz g C-S LOEI Mz K Mz P g g V TR m SUKHOTHAI D-C TR Mz P K Cz Mz Mz V g P 16° Mz TR Mz Mz P m V 16° V K g K g P Cz V V C-S P D-C KHORAT C-S C-S K P g g Cz V Mz g V V V g Mz 14° P KANCHANABURI 14° Cz P BANGKOK V TR g V TR C-S g m P P g g Cz m V D-C TR V P m CHANTHABURI m Mz Cz P TR 12° V ° Cz Mz 12 g K P Mz SEDIMENTARY ROCKS g 10° Cz g Mz Cenozoic g g P g K Cretaceous P Mz Mesozoic (undifferentiated) m TR P Triassic Mz g P Permian (locally including Triassic and Carboniferous) g P D-C Devonian-Carboniferous (locally including Silurian and Permian) ° KRABI Cz 8 PHUKET Mz Mz C-S Cambrian-Silurian D-C g IGNEOUS & METAMORPHIC ROCKS Mz g Granite/ V SONGKHLA Cenozoic C-S Granodiorite basalts m Gneiss, Cz V Acid volcanic C-S migmatite TR rocks g D-C Basic/ultrabasic rocks Cz g 6° ° 98 E 100° 102° 104° 106° Modified from the Thailand Department of Mineral Resources geological map, 1:2,000,000 scale, 1999. -

Whether Loyalty to a Football Club Can Translate Into a Political Support for the Club Owner: an Empirical Evidence from Thai League

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 11, No. 3; 2018 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Whether Loyalty to a Football Club Can Translate into a Political Support for the Club Owner: An Empirical Evidence from Thai League Thanaporn Sriyakul1, Anurak Fangmanee2 & Kittisak Jermsittiparsert3, 4 1 Faculty of Business Administration, Mahanakorn University of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand 2 Khon Kaen United F.C., Khon Kaen, Thailand 3 Department for Management of Science and Technology Development, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam 4 Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Correspondence: Kittisak Jermsittiparsert, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 13, 2018 Accepted: May 20, 2018 Online Published: August 30, 2018 doi:10.5539/jpl.v11n3p47 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v11n3p47 Abstract The participation of politicians and their kin in the sport of football, as presidents of football clubs, in the past many years has been widely criticized as a use of the football clubs as tools to gain popularity and, possibly, a political base or a voting bloc for these politicians. This research is conducted in order to (1) study the loyalty level towards football clubs and the corresponding political supports expressed towards the football club executives and (2) examine the relationship between such demographic factors as gender, age, educational level, occupation, income, duration of being a fan, as well as loyalty to the football club and the aforementioned political supports, by collecting data from fans of five football clubs competing in the Thai League during the 2016 season. -

Phanom Rung Festival

SPONSORED SECTION BURIRAM and Beyond Home to uncrowded ancient sites, spellbinding cultural festivals, and one of Thailand’s best-loved regional cuisines, Isan is ripe for discovery. SPONSORED SECTION Phimai Dan Kwiam Pottery Village Bangkok Surin Phanom City Rung PHANOM RUNG FESTIVAL reveler praised the e-tan, or farmers’ My first stop in Isan is Buriram, a trucks, used during the MotoGP as a province whose namesake capital has shuttle service to and from the venue. emerged in recent years as a sporting But now, in early April, all is quiet destination. The town is home to one of at Chang International Circuit and the AmericanAs who has livedan on-and-off the best-performing football teams in grandstands are devoid of spectators. in Bangkok the past three years, I’m the country, and its five-year-old Chang I’ve come to Buriram for something sometimes struck by how much of International Circuit will play host to quite different: the Phanom Rung Thailand I haven’t yet seen. So when I Thailand’s second MotoGP event this Festival, an extravaganza that takes recently got the chance to embark on October. Phil Ramsey, a visitor who place at an 800-year-old Khmer temple. a nine-day trip through Isan, that vast attended the inaugural races last year, Phanom Rung may not have the northeastern region overlooked by most recalled a “fun crowd” and touted it as global fame of Angkor Wat, but it foreign visitors, there was no way I could a “brilliant first GP for the kingdom, with should.