1 John Constable Is One of the Most Famous English Landscape Painters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Constable (1776-1837)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN John Constable (1776-1837) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Hadleigh Farm and Country Park Green Infrastructure Case Study the Olympic Mountain Biking Venue for London 2012

Hadleigh Farm and Country Park Green Infrastructure Case Study The Olympic mountain biking venue for London 2012 The creation of an elite mountain biking venue at Hadleigh Farm in Key facts: Essex for the London 2012 Olympic Games provided an opportunity to expand investment in the long-term sporting and recreational Size of the Olympic Mountain facilities within the area. A partnership between landowners, councils Biking Venue: 220 ha (550 acres) and Natural England has capitalised on this opportunity to enhance Combined size of Hadleigh green infrastructure and improve the quality and accessibility of the Farm (Salvation Army) and Country Park (Essex County natural environment for the benefit of local communities and visitors. Council): 512 ha (1,287 acres) The Country Park is one of the largest in Essex and used by Snapshot around 125,000 visitors per year Selection as an Olympic venue provided the catalyst for short The site includes areas and long-term investment designated as a Site of Special Elite and general mountain biking facilities integrated with Scientific Interest, a Special nature conservation objectives Protection Area and Ramsar site (Wetlands of International Legacy facilities for sport and recreation are projected to Importance, especially as increase the number and mix of visitors waterfowl habitat) and a Local Improved accessibility to local green infrastructure has Wildlife Site, and contains promoted healthy and active communities several Scheduled Monuments Construction work on the Olympic course began in July -

Hadleigh Castle & Chalkwell Oaze

1 Hadleigh Castle & Chalkwell Oaze Benfleet station - Hadleigh Castle - Leigh-on-Sea - Chalkwell station An easy stroll through Thames-side marshes, climbing to the spectacular ruins of Hadleigh Castle, before a wander through the lovely fishing village of Old Leigh and along the promenade to Chalkwell. Length: 5 ½ miles (8.9km) Useful websites: The route passes through Hadleigh Castle Country Park and Underfoot: Some of the first section past the castle itself. It also passes through through the marshes and meadows can be the centre of the fishing village of Old muddy after rain. Other sections are well Leigh. drained or surfaced paths. Getting home: Chalkwell has 6 trains an Terrain: Almost entirely flat, except for hour (4 on Sundays) to London Fenchurch the short, steep ascent to Hadleigh Castle Street (50-69 mins) via Barking (33-52 and a very gentle descent from it. mins) for London Underground and London Overground connections and West Maps: 1:50,000 Landranger 178 Thames Ham (39-58 mins) for London Estuary; 1:25,000 Explorer 175 Southend- Underground and DLR connections. Four on-Sea & Basildon. trains per hour call at Limehouse (47-54 mins) for DLR connections. Getting there: Benfleet is served by 6 c2c services per hour (4 per hour on Sundays) Fares: The cheapest option is to purchase from London Fenchurch Street (38-59 a super off-peak day return to Chalkwell, mins). All trains call at West Ham (30-50 which will cover both journeys, for £10.90 mins) for London Underground and DLR (£5.45 child, £7.20 railcard). -

Hadleigh Park Priority Species Habitat Assessment 2015

Hadleigh Park priority species habitat assessment 2015 Hadleigh Park priority species habitat assessment 2015 Authors: Connop, S. and Clough, J. Corresponding author: Stuart Connop ([email protected]) Published by the University of East London 4-6 University Way Docklands London E16 2RD Cover photo: White-letter hairstreak on bramble © Stuart Connop © University of East London 2016 Printed in Great Britain at the University of East London, Docklands, London. Connop, S. and Clough, J. 2016. Hadleigh Park priority species habitat assessment. London: University of East London. 1 | P a g e Contents 1. Background ........................................................................................................................6 2. White-letter hairstreak butterfly survey ...............................................................................8 3. Green haying forage creation experiment ..........................................................................18 4. Bumblebee survey ............................................................................................................45 5. Habitat management recommendations ............................................................................66 6. References .......................................................................................................................68 Appendix 1 ...........................................................................................................................70 2 | P a g e Figures Figure 1. Hadleigh Park Compartment -

British Art Studies June 2018 British Art Studies Issue 8, Published 8 June 2018

British Art Studies June 2018 British Art Studies Issue 8, published 8 June 2018 Cover image: Unidentified photographer, possibly Elsie Knocker, “Selfand Jean- Batiste”, Mairi Chisholm with Jean Batiste, a Belgian Congolese soldier, undated. Digital image courtesy of National Library of Scotland. PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents “As if every particle was alive”: The Charged Canvas of Constable’s Hadleigh Castle, Damian Taylor “As if every particle was alive”: The Charged Canvas of Constable’s Hadleigh Castle Damian Taylor Abstract John Constable painted Hadleigh Castle in the months that followed the death of his wife, Maria, in late 1828. -

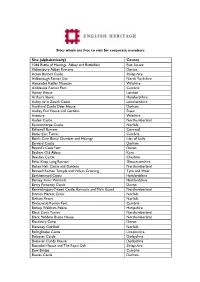

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Greater Thames Research Framework 2010

THE GREATER THAMES ESTUARY HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 2010 Update and Revision of the Archaeological Research Framework for the Greater Thames Estuary (1999) THE GREATER THAMES ESTUARY HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Update and Revision of the Archaeological Research Framework for the Greater Thames Estuary (1999) June 2010 Prepared by Essex County Council, Historic Environment Branch On the behalf of Greater Thames Estuary Archaeological Steering Committee THE GREATER THAMES ESTUARY HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Update and Revision of the Archaeological Research Framework for the Greater Thames Estuary’ (1999) Project Title: Greater Thames Estuary Research Framework Review English Heritage Proj. Ref: 5084 ECC Proj. Ref: 1592 Prepared by: E M Heppell (EMH) Project Officer, Essex County Council Field Archaeology Unit Fairfield Court Fairfield Road Braintree CM7 3YQ e-mail: [email protected] Tel: 01376 331431 Derivation: 1592GTRF_draft_feb10 Origination Date: July 2009 Date of document: Nov 2010 Version: 6 Status: Final document Summary of changes: Final report Circulation: General circulation Filename and location: ECC FAU, Braintree H:/fieldag/project/1592/text/1592GRRF_Final_Nov10.doc CONTENTS PART 1 FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 THE DEVELOPMENT AND PALAEOENVIRONMENT OF THE THAMES ESTUARY 2.1 The Thames through Time 2.2 Palaeolithic and Mesolithic 2.3 Relative Sea-level 2.4 Recent Projects Lower Palaeolithic (pre-425 kBP; MIS 12 and earlier) Lower to Middle Palaeolithic (415–125 -

CURRICULUM VITAE Paul H

CURRICULUM VITAE Paul H. Fry William Lampson Professor of English, Emeritus Yale University Office: Henry Koerner Center, Rm. 118 Yale University New Haven, CT 06520 203-824-3761 [email protected] EDUCATION AND DEGREES Harvard University. May 1974 Ph. D. Dissertation: “Byron’s Myth of the Self” University of California, Berkeley. 1966 B. A. GRANTS AND AWARDS 2018. Juror, Brock International Teaching Prize 2011. Winner, Stephen Sondheim Inspirational Teaching Award, Kennedy Center for the Arts 2008- Appointed Associate Member, Department of Comparative Literature, Yale 2008- Awarded Provostial Research Fund. Fall 2008-Spring 2009. Residency, Yale Center for British Art, to develop an interdisciplinary course syllabus. Fall 2002-Spring 2003. Full-year Leave of Absence 1999. Reappointed: Master, Ezra Stiles College, Yale 1995. Named: Master, Ezra Stiles College, Yale 1993. Named: The William Lampson Professor of English 1989. A. Whitney Griswold Research Grant 1988. Named Instructor, NEH Faculty Seminar, Summer 1989 1987. Honorable Mention, the John H. McGinnis Award, Southwest Review 1986. Promoted to Full Professor, Yale University. 1985. Appointed Fellow, Whitney Humanities Center (1985-88) 1982. Granted Tenure, Yale University 1981. The Melville Cane Award (Poetry Society of America) for The Poet’s Calling in the English Ode 1979. Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund 1978. A. Whitney Griswold Research Grant 1976-77. Morse Fellowship 1971. Charles William Eliot Medal, Eliot House, Harvard University 1971. Assistant Senior Tutor, Eliot House, Harvard University 1970. Dexter Summer Grant, Harvard University 1966-67. Woodrow Wilson Fellowship 1966. Outstanding Undergraduate English Major, University of California, Berkeley 1965. Phi Beta Kappa TEACHING EXPERIENCE Spring 2020, emeritus graduate seminar, “Byron, Shelley and Keats” Spring 2019, emeritus seminar, “Romantic Literature and Painting” Phased Retirement 2016-18. -

ENGLISH LANDSCAPE ARTISTS Drawings and Prints Prints and Drawings Galleries/June 26-September 6,1971

ENGLISH LANDSCAPE ARTISTS Drawings and Prints Prints and Drawings Galleries/June 26-September 6,1971 r,«> V ' ^JKtA^fmrf .^r*^{. v! •,\ ^ ^fc-^i I- 0 It has long been recognised that there is a special affinity between the English people and landscape. As painters and sketchers of landscape, as lyrical nature poets, and as landscape gardeners (of the Nature-Arranged school as distinct from the formal continental embroidery-parterre style) the XVIIIth and early XlXth century English outstripped everyone else. Moved by more than just the romantic spirit of the times, the English, although fascinated by impassioned anthropomor phic renderings of storms, also enjoyed serene pictures of the familiar out-of-doors. Starting at least as far back as the XVIIth century with a topographical interest, portraits of their own homes and countryside have always appealed to the English, the way color snapshots of favorite places still do. The people who could afford to have painters and engravers make bird's-eye views of their house and grounds in the XVIIth century were also travelling on the continent, looking at the Roman campagna and collecting both paintings and drawings of it to take home. By the XVIIIth century, having trained their eyes to accept and even enjoy drawings, English gentlemen hired drawing masters to teach their children how to "take a landskip". Many a drawing master and even well-known painters, finding that they needed to supplement meagre incomes, wrote and illustrated books of instruction. While a few drawing books were produced elsewhere, they were mainly devoted to figure drawing, but the English (and also the American) ones were extremely nu merous, and almost entirely devoted to landscape. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 508 6 April 2010 No. 67 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 6 April 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 797 6 APRIL 2010 798 David Miliband: I am sorry that this will be the last House of Commons occasion on which my hon. Friend asks a question in this House; she has raised a very important point. On education, one can point to a qualitative shift. There are Tuesday 6 April 2010 now, after all, about 6 million to 7 million children in school in Afghanistan, nearly half of them girls, which is The House met at half-past Two o’clock a complete revolution in comparison with a decade ago. In other areas, however, as we heard from the civil society representatives at the London conference, progress PRAYERS has been much slower, including in areas such as political representation and health care, which my hon. Friend mentioned. [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr. William Hague (Richmond, Yorks) (Con): Amidst all the debates that we will have in the coming election campaign, should we not all remember that throughout Oral Answers to Questions every hour of it we have 10,000 British servicemen and women in real battles in Afghanistan and that their role must be a paramount concern for whoever is elected on FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE 6 May? Is it not true that the military advances made on the ground will be of long-term benefit only if the The Secretary of State was asked— Afghan political processes also succeed and are seen to be legitimate? When the Prime Minister announced Afghanistan UK strategy for Afghanistan in November last year, he pledged that President Karzai would ensure that all 1. -

Castles – East

Castles – East ‘Build Date’ refers to the oldest surviving significant elements In column 1; CM ≡ Cambridgeshire, E ≡ Essex, L ≡ Lincolnshire, NF ≡ Norfolk, SF ≡ Suffolk Build Occupation CM Castle Location Configuration Current Remains Date Status 1 Buckden Towers TL 193 677 Fortified house 15th C Occupied Tower, gatehouse, entire 2 Burwell TL 587 661 Enclosure? 1144 Empty, never completed Earthworks 3 Cambridge TL 446 593 Motte & bailey 1068 Empty, 17th C then 19th C Motte earthwork 4 Kirtling Towers TL 685 575 Fortified house 15/16th C Demolished, 1801 Gatehouse now a house 5 Longthorpe TL 163 984 Tower & hall 13th C Occupied Tower, hall entire E 1 Colchester TL 999 253 Keep & bailey c1075 Museum Keep, restored 2 Great Canfield TL 594 179 Motte & bailey 11th C Empty, wooden only Earthworks 3 Hadleigh TQ 810 861 Enclosure Early-13th C Empty, late-16th C Fragmentary ruins 4 Hedingham TL 787 358 Keep & bailey Mid-12th C Empty, 17th C Keep entire, bridge 5 Pleshey TL 665 145 Motte & bailey Late-11th C Empty, 15th C Earthworks, bridge 6 Saffron Walden TL 540 397 Motte & bailey 1140 Empty, never completed Ruined keep L 1 Bolingbroke TF 349 650 Enclosure Early-12th C Empty, 17th C Low ruins 2 Bytham SK 991 185 Enclosure + keep Early 13th C Empty, 16th C Earthworks only 3 Grimsthorpe TF 044 227 Quadrangular 14th C Occupied, remodelled One original tower 4 Hussey TF 333 436 Tower Mid-15th C Empty, sleighted 16th C Roofless but near full height 5 Lincoln SK 975 719 Enclosure + keep 11th C Occupied Older parts ruined 6 Rochfort TF 351 444 Tower -

Metrotidal Tunnel Text

METROTIDAL TUNNEL JULY 2013 TUNNEL AGENDA CONTENTS 1 Introduction and Executive Summary 2 The Tunnel Agenda 2.1 Agglomeration Benefits 2.2 Integration Benefits 2.3 Multi-Modal Tunnel vs Road-Only Bridge 2.4 Lower Thames Tunnel 2.5 Tunnel construction 2.6 Tunnel connections 2.7 Flood defence 2.8 Tidal power 2.9 Data storage and Utilities 2.10 Ancillary Development 2.11 Passengers and freight 2.12 Leigh-on-Sea Option 4 Summary of the Agglomeration and Integration benefits 4.1 Metrotidal Tunnel benefits copyright (c) 2013 Metrotidal Ltd., London 1 1 INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Metrotidal Tunnel and Thames Reach Airport are independent private sector initiatives, the first a solution to providing a new Lower Thames Tunnel, the second a new hub airport in the Thames Estuary. While the initiatives are independent they can be fully co-ordinated, with the tunnel providing surface access for a hub airport developed in phases. Metrotidal Tunnel integrates a multi-modal Lower Thames Tunnel with new flood defences for London, tidal power and data storage. The integrated tunnel infrastructure provides economic growth without an associated increase in carbon audit. This green-growth is achieved through improved transport connectivity, with emphasis on rail, integrated with a flood defence system and tidal power plant that generates and stores renewable energy for supply on demand. The tidal plant includes energy-efficient data storage and distribution. These green-growth agglomeration benefits extend beyond the Thames Estuary region across London and the Greater Southeast. Thames Reach Airport is the phased construction of a new, 24-hour, hub airport on the Isle of Grain purpose-designed to be time and energy efficient, providing the shortest times for transfer and transit and the lowest carbon audit per passenger; air-side, land-side and for the surface access.