'The Art of Seeing Nature' Ten Drawings by John Constable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articled to John Varley

N E W S William Blake & His Followers Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Winter 1982/1983, p. 184 PAGE 184 BLAKE AN I.D QlJARThRl.) WINTER 1982-83 NEWSLETTER WILLIAM BLAKE & HIS FOLLOWERS In conjunction with the exhibition William Blake and His Followers at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Morton D. Paley (Univ. of California, Berkeley) delivered a lecture, "How Far Did They Follow?" on 16 January BLAKE AT CORNELL 1983. Cornell University will host Blake: Ancient & Modern, a symposium 8-9 April 1983, exploring the ways in which the traditions and techniques of printmaking and painting JOHN LINNELL: A CENTENNIAL EXHIBITION affected Blake's poetry, art, and art theory. The sym- posium will also discuss Blake's late prints and the prints We have received the following news release from the of his followers, and examine the problems of teaching Yale Center for British Art: in college an interdisciplinary artist like William Blake. The first retrospective exhibition in America of the Panelists and speakers include M. H. Abrams, Esther work of John Linnell will open at the Yale Center for Dotson, Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, Peter Kahn, British Art on Wednesday, 26 January. Karl Kroeber, Reeve Parker, Albert Roe, Jon Stallworthy, John Linnell was born in London on 16 June 1792. He and Joseph Viscomi. died ninety years later, after a long and successful career The symposium is being held in conjunction with two ex- which spanned a century of unprecedented change in hibitions: The Prints of Blake and his Followers, Johnson Britain. -

The Controversial Treatments of the Wallace Collection

HOME ABOUT US THE JOURNAL MEMBERSHIP ARCHIVE LINKS 8 September 2011 The Controversial Treatments of the Wallace Collection Watteaus Restorers who blunder often present their dramatically altered works as miraculous “recoveries” or “discoveries”. Sometimes they (or their curators) park their handiwork in dark corners pending re-restorations (see the Phillips Collection restoration of Renoir’s “The Luncheon of the Boating Party” and the Louvre’s multi- restoration of Veronese’s “The Pilgrims of Emmaüs”). Here, Dr Selby Whittingham, the Secretary-General of the Watteau Society (and the 2011 winner of ArtWatch International’s Frank Mason Prize – see below), discusses the controversial restorations of Watteau paintings at the Wallace Collection and calls for greater transparency and accountability in the treatment of old masters. Above, Fig. 1: “Les charmes de la vie”, (reversed) engraving by Pierre Aveline, after Antoine Watteau, the British Museum, London. Selby Whittingham writes: The Watteau exhibitions held in London 12 March – 5 June 2011 prompted much comment, but little about the condition of the oils at the Wallace Collection [- see endnote 1]. Exceptionally Brian Sewell mentioned their poor state: “both overcleaned and undercleaned, victims of cleaners with Brillo pads and restorers with a taste for gravy.” [2] This was a bit sweeping, but had some justification. In the Watteau Society Bulletin 1985 Sarah Walden contrasted the recent restorations at the Wallace Collection with those at the Louvre and the Above, Fig. 2: Watteau’s “Les charmes de la vie” as reproduced in the Wallace Collection’s 1960 volume of different philosophies behind them [3]. The report illustrations of pictures and drawings to accompany the on the cleaning of “Les Charmes de la vie” at the Catalogue of Pictures and Drawings. -

Book of Abstracts: Studying Old Master Paintings

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS STUDYING OLD MASTER PAINTINGS TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE THE NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN 30TH ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE 1618 September 2009, Sainsbury Wing Theatre, National Gallery, London Supported by The Elizabeth Cayzer Charitable Trust STUDYING OLD MASTER PAINTINGS TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE THE NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN 30TH ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1618 September 2009 Sainsbury Wing Theatre, National Gallery, London The Proceedings of this Conference will be published by Archetype Publications, London in 2010 Contents Presentations Page Presentations (cont’d) Page The Paliotto by Guido da Siena from the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Siena 3 The rediscovery of sublimated arsenic sulphide pigments in painting 25 Marco Ciatti, Roberto Bellucci, Cecilia Frosinini, Linda Lucarelli, Luciano Sostegni, and polychromy: Applications of Raman microspectroscopy Camilla Fracassi, Carlo Lalli Günter Grundmann, Natalia Ivleva, Mark Richter, Heike Stege, Christoph Haisch Painting on parchment and panels: An exploration of Pacino di 5 The use of blue and green verditer in green colours in seventeenthcentury 27 Bonaguida’s technique Netherlandish painting practice Carole Namowicz, Catherine M. Schmidt, Christine Sciacca, Yvonne Szafran, Annelies van Loon, Lidwein Speleers Karen Trentelman, Nancy Turner Alterations in paintings: From noninvasive insitu assessment to 29 Technical similarities between mural painting and panel painting in 7 laboratory research the works of Giovanni da Milano: The Rinuccini -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

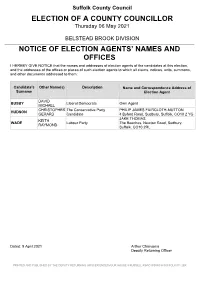

Notice of Election Agents Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent DAVID BUSBY Liberal Democrats Own Agent MICHAEL CHRISTOPHER The Conservative Party PHILIP JAMES FAIRCLOTH-MUTTON HUDSON GERARD Candidate 4 Byford Road, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 2 YG JAKE THOMAS KEITH WADE Labour Party The Beeches, Newton Road, Sudbury, RAYMOND Suffolk, CO10 2RL Dated: 9 April 2021 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE DEPUTY RETURNING OFFICER ENDEAVOUR HOUSE 8 RUSSELL ROAD IPSWICH SUFFOLK IP1 2BX Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 COSFORD DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent GORDON MEHRTENS ROBERT LINDSAY Green Party Bildeston House, High Street, Bildeston, JAMES Suffolk, IP7 7EX JAKE THOMAS CHRISTOPHER -

Constable Free

FREE CONSTABLE PDF John Sunderland | 128 pages | 12 Aug 1998 | Phaidon Press Ltd | 9780714827544 | English | London, United Kingdom Constable | Definition of Constable by Merriam-Webster John Constableborn June 11, Constable, East Bergholt, SuffolkEngland—died March 31,Constablemajor figure in English landscape painting in the early 19th century. The son of a wealthy miller and merchant who owned a substantial house and small farm, Constable was reared in a small Suffolk village. The environs of his childhood and his understanding of its rural economy would later figure prominently in his work. In February he made himself known to the influential academician Joseph Farington, and in March he entered the prestigious Royal Academy schools, with the grudging approval of his father. Constable the Constable, art academies stressed Constable painting as the most appropriate subject Constable for their students, but from the beginning Constable showed a particular interest in landscape. In Constable refused the stability of a post as drawing master at a military academy so that he could instead dedicate himself to landscape painting and to studying nature Constable in the English countryside. That same year he exhibited his work at the Royal Academy for the first time. Despite some early explorations in oil, in the first part of this Constable he preferred using watercolour and graphic media in Constable studies of nature. He produced fine studies in these media during a trip to Constable famously picturesque Lake District in autumnbut his exhibitions of these works in both and were unsuccessful in attracting public notice. Although based in London during this period, Constable would frequently make extended visits to his native East Bergholt to sketch. -

Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable

return to list of Publications and Lectures Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable Charles S. Rhyne Professor, Art History Reed College published in Appearance, Opinion, Change: Evaluating the Look of Paintings Papers given at a conference held jointly by the United Kingdom institute for Conservation and the Association of Art Historians, June 1990. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 1990, p.72-84. Abstract This paper reviews the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by one artist, John Constable. The intention is not simply to describe changes in the work of Constable but to suggest a framework for the study of changes in the work of any artist and to facilitate discussion among conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and art historians. The paper considers, first, examples of physical changes in the paintings themselves; second, changes in the physical conditions under which Constable's paintings have been viewed. These same examples serve to consider changes in the cultural and psychological contexts in which Constable's paintings have been understood and interpreted Introduction The purpose of this paper is to review the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by a single artist to see what questions these raise and how the varying answers we give to them might affect our work as conservators, scientists, curators, and historians. [1] My intention is not simply to describe changes in the appearance of paintings by John Constable but to suggest a framework that I hope will be helpful in considering changes in the paintings of any artist and to facilitate comparisons among artists. -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Tate Papers - Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance

Tate Papers - Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance ... http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/08spring/congd... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance of Constable's Glebe Farm Sketch c.1830 Douglas Congdon-Martin At the death of Sir Edwin Manton, the great benefactor of the Tate Britain, on 1 October 2005, one of the mysteries he left behind was the provenance of the sketch for John Constable’s The Glebe Farm , c.1830 ( Tate T12293 ), on loan to Tate from 1998, before being transferred to the gallery as a gift in 2006 The Glebe Farm canon When it was rediscovered in the mid 1990s, Sir Edwin’s picture joined the canon of Constable’s Glebe Farm paintings. The subject, a cottage and lane scene with the tower of the Langham church, Essex, was a favourite of the artist. In December 1836 he wrote to C.R. Leslie: ‘Sheepshanks means to have my Glebe Farm, or Green Lane, of which you have a sketch. This is one of the pictures on which I rest my little pretensions of futurity.’ 1 There are five versions currently known. The earliest is an oil sketch in the Victoria and Albert Museum (No.161–1888, fig.2), given by the artist’s children in 1888. Undated, it is generally thought to have been painted between 1810 and 1815 .2 The sketch is almost certainly the basis for the later pictures, but lacks the church tower. Fig.2 John Constable Church Farm, Langham c.1810–15 Isabel Constable; given by her in 1888 © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London 1 of 18 25/01/2012 11:13 Tate Papers - Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance .. -

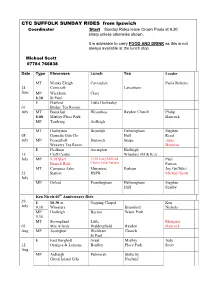

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides Leave Crown Pools at 9.30 Sharp Unless Otherwise Shown

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides leave Crown Pools at 9.30 sharp unless otherwise shown. It is advisable to carry FOOD AND DRINK as this is not always available at the lunch stop Michael Scott 07784 766838 Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea Leader MT Monks Eleigh Cavendish Paula Roberts 24 Corncraft Lavenham June MP Wickham Clare 8.30 St Paul E Flatford Little Horkesley 01 Bridge Tea Rooms July MT Breakfast Wivenhoe Raydon Church Philip 8.00 Mistley Place Park Hancock MP Tendring Ardleigh MT Hacheston Brundish Helmingham Stephen 08 Garnetts Gdn Ctr Hall Read July MP Peasenhall Dunwich Snape Anna Weavers Tea Room Brennan E Dedham Assington Hadleigh 15 Craft Centre Wheelers (M & K’s) July MP 9.30 Start 11.30 Long Melford Paul Brunch Ride Cherry Lane Nursery Fenton MT Campsea Ashe Minsmere Parham Joy Griffiths/ 22 Station RSPB Michael Scott July MP Orford Framlingham Helmingham Stephen Hall Searby Ken Nicols 60th Anniversary Ride 29 E 10.30 at Gipping Chapel Ken July 9.30 Wheelers Bramford Nichols MP Hadleigh Bacton Water Park 9.30 MT Stowupland Little Margaret 05 Mrs Allards Waldingfield Raydon Hancock Aug MP Assington Wickham Church St Paul E East Bergholt Great Mistley Judy 12 Oranges & Lemons Bentley Place Park Scott Aug MP Ardleigh Pebmarsh Stoke by Green Island Gdn Nayland Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea MT Breakfast South Stowmarket Michael 19 7.30 Stoke Ash Lopham Scott Aug MP Breakfast Surlingham Train Home Colin 7.30 Tivetshall Clarke E Debenham Thornham Needham Mkt River Green Alder Carr E Hollesley -

John Constable (1776-1837)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN John Constable (1776-1837) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1.