John Constable (1776-1837)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articled to John Varley

N E W S William Blake & His Followers Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Winter 1982/1983, p. 184 PAGE 184 BLAKE AN I.D QlJARThRl.) WINTER 1982-83 NEWSLETTER WILLIAM BLAKE & HIS FOLLOWERS In conjunction with the exhibition William Blake and His Followers at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Morton D. Paley (Univ. of California, Berkeley) delivered a lecture, "How Far Did They Follow?" on 16 January BLAKE AT CORNELL 1983. Cornell University will host Blake: Ancient & Modern, a symposium 8-9 April 1983, exploring the ways in which the traditions and techniques of printmaking and painting JOHN LINNELL: A CENTENNIAL EXHIBITION affected Blake's poetry, art, and art theory. The sym- posium will also discuss Blake's late prints and the prints We have received the following news release from the of his followers, and examine the problems of teaching Yale Center for British Art: in college an interdisciplinary artist like William Blake. The first retrospective exhibition in America of the Panelists and speakers include M. H. Abrams, Esther work of John Linnell will open at the Yale Center for Dotson, Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, Peter Kahn, British Art on Wednesday, 26 January. Karl Kroeber, Reeve Parker, Albert Roe, Jon Stallworthy, John Linnell was born in London on 16 June 1792. He and Joseph Viscomi. died ninety years later, after a long and successful career The symposium is being held in conjunction with two ex- which spanned a century of unprecedented change in hibitions: The Prints of Blake and his Followers, Johnson Britain. -

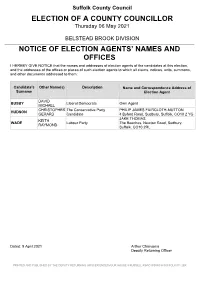

Notice of Election Agents Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent DAVID BUSBY Liberal Democrats Own Agent MICHAEL CHRISTOPHER The Conservative Party PHILIP JAMES FAIRCLOTH-MUTTON HUDSON GERARD Candidate 4 Byford Road, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 2 YG JAKE THOMAS KEITH WADE Labour Party The Beeches, Newton Road, Sudbury, RAYMOND Suffolk, CO10 2RL Dated: 9 April 2021 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE DEPUTY RETURNING OFFICER ENDEAVOUR HOUSE 8 RUSSELL ROAD IPSWICH SUFFOLK IP1 2BX Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 COSFORD DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent GORDON MEHRTENS ROBERT LINDSAY Green Party Bildeston House, High Street, Bildeston, JAMES Suffolk, IP7 7EX JAKE THOMAS CHRISTOPHER -

Constable Free

FREE CONSTABLE PDF John Sunderland | 128 pages | 12 Aug 1998 | Phaidon Press Ltd | 9780714827544 | English | London, United Kingdom Constable | Definition of Constable by Merriam-Webster John Constableborn June 11, Constable, East Bergholt, SuffolkEngland—died March 31,Constablemajor figure in English landscape painting in the early 19th century. The son of a wealthy miller and merchant who owned a substantial house and small farm, Constable was reared in a small Suffolk village. The environs of his childhood and his understanding of its rural economy would later figure prominently in his work. In February he made himself known to the influential academician Joseph Farington, and in March he entered the prestigious Royal Academy schools, with the grudging approval of his father. Constable the Constable, art academies stressed Constable painting as the most appropriate subject Constable for their students, but from the beginning Constable showed a particular interest in landscape. In Constable refused the stability of a post as drawing master at a military academy so that he could instead dedicate himself to landscape painting and to studying nature Constable in the English countryside. That same year he exhibited his work at the Royal Academy for the first time. Despite some early explorations in oil, in the first part of this Constable he preferred using watercolour and graphic media in Constable studies of nature. He produced fine studies in these media during a trip to Constable famously picturesque Lake District in autumnbut his exhibitions of these works in both and were unsuccessful in attracting public notice. Although based in London during this period, Constable would frequently make extended visits to his native East Bergholt to sketch. -

Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable

return to list of Publications and Lectures Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable Charles S. Rhyne Professor, Art History Reed College published in Appearance, Opinion, Change: Evaluating the Look of Paintings Papers given at a conference held jointly by the United Kingdom institute for Conservation and the Association of Art Historians, June 1990. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 1990, p.72-84. Abstract This paper reviews the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by one artist, John Constable. The intention is not simply to describe changes in the work of Constable but to suggest a framework for the study of changes in the work of any artist and to facilitate discussion among conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and art historians. The paper considers, first, examples of physical changes in the paintings themselves; second, changes in the physical conditions under which Constable's paintings have been viewed. These same examples serve to consider changes in the cultural and psychological contexts in which Constable's paintings have been understood and interpreted Introduction The purpose of this paper is to review the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by a single artist to see what questions these raise and how the varying answers we give to them might affect our work as conservators, scientists, curators, and historians. [1] My intention is not simply to describe changes in the appearance of paintings by John Constable but to suggest a framework that I hope will be helpful in considering changes in the paintings of any artist and to facilitate comparisons among artists. -

January 14 Mono Sectionbrn

Box River News Boxford • Edwardstone • Groton • Little Waldingfield • Newton Green January 2014 Vol 14 No 1 A Very Merry Christmas and a Happy and Healthy New Year to you all Scrooge the Panto, see inside 3PR’S YVONNE HUGHES RETIRES SAND HILL DEVELOPMENT Dear Editor Parish Council Meeting 2nd December 2013 – in the School Hall Some 50 residents of the village attended this meeting to discuss the planning application for the development of the Sand Hill site. Both the Boxford Society and the YourBoxford groups submitted well thought out and professional objections to this site for affordable housing, based on existing regulations. Unfortunately none of our concerns were discussed nor were we able to put questions on the planning application to the Parish Council. It is a sad day when concerned residents who are anxious to work with the Councillors for the best outcome for villagers who are to be rehomed in Boxford, have been dismissed There were two residents who spoke in favour of the site, stating they were concerned their children would not be able to live in the village in the future. Details of our concerns and residents comments can be found on the Yourboxford.org website. If anyone still wants to add their concerns to Babergh, the end date for submitting letters is 17th December. Please write to: Mr. G. Chamberlain, quoting Application Number B/13/01200/FUL copy to Christine Thurlow who is the Corporate Manager – Development Management, at Babergh D.C. Council Offices, Corks Lane, Hadleigh IP7 6SJ. Alternately you can e-mail it to: [email protected] or [email protected] Sue Beven.Yourboxford.org Box River News Telephone: 01787 211507 Yvonne Hughes, one of 3PR responders has retired from the group. -

Tate Papers - Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance

Tate Papers - Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance ... http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/08spring/congd... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance of Constable's Glebe Farm Sketch c.1830 Douglas Congdon-Martin At the death of Sir Edwin Manton, the great benefactor of the Tate Britain, on 1 October 2005, one of the mysteries he left behind was the provenance of the sketch for John Constable’s The Glebe Farm , c.1830 ( Tate T12293 ), on loan to Tate from 1998, before being transferred to the gallery as a gift in 2006 The Glebe Farm canon When it was rediscovered in the mid 1990s, Sir Edwin’s picture joined the canon of Constable’s Glebe Farm paintings. The subject, a cottage and lane scene with the tower of the Langham church, Essex, was a favourite of the artist. In December 1836 he wrote to C.R. Leslie: ‘Sheepshanks means to have my Glebe Farm, or Green Lane, of which you have a sketch. This is one of the pictures on which I rest my little pretensions of futurity.’ 1 There are five versions currently known. The earliest is an oil sketch in the Victoria and Albert Museum (No.161–1888, fig.2), given by the artist’s children in 1888. Undated, it is generally thought to have been painted between 1810 and 1815 .2 The sketch is almost certainly the basis for the later pictures, but lacks the church tower. Fig.2 John Constable Church Farm, Langham c.1810–15 Isabel Constable; given by her in 1888 © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London 1 of 18 25/01/2012 11:13 Tate Papers - Sir Edward Manton's Glebe: Completing the Provenance .. -

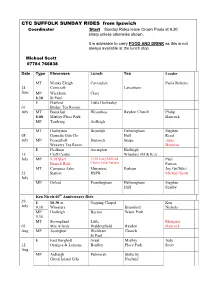

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides Leave Crown Pools at 9.30 Sharp Unless Otherwise Shown

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides leave Crown Pools at 9.30 sharp unless otherwise shown. It is advisable to carry FOOD AND DRINK as this is not always available at the lunch stop Michael Scott 07784 766838 Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea Leader MT Monks Eleigh Cavendish Paula Roberts 24 Corncraft Lavenham June MP Wickham Clare 8.30 St Paul E Flatford Little Horkesley 01 Bridge Tea Rooms July MT Breakfast Wivenhoe Raydon Church Philip 8.00 Mistley Place Park Hancock MP Tendring Ardleigh MT Hacheston Brundish Helmingham Stephen 08 Garnetts Gdn Ctr Hall Read July MP Peasenhall Dunwich Snape Anna Weavers Tea Room Brennan E Dedham Assington Hadleigh 15 Craft Centre Wheelers (M & K’s) July MP 9.30 Start 11.30 Long Melford Paul Brunch Ride Cherry Lane Nursery Fenton MT Campsea Ashe Minsmere Parham Joy Griffiths/ 22 Station RSPB Michael Scott July MP Orford Framlingham Helmingham Stephen Hall Searby Ken Nicols 60th Anniversary Ride 29 E 10.30 at Gipping Chapel Ken July 9.30 Wheelers Bramford Nichols MP Hadleigh Bacton Water Park 9.30 MT Stowupland Little Margaret 05 Mrs Allards Waldingfield Raydon Hancock Aug MP Assington Wickham Church St Paul E East Bergholt Great Mistley Judy 12 Oranges & Lemons Bentley Place Park Scott Aug MP Ardleigh Pebmarsh Stoke by Green Island Gdn Nayland Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea MT Breakfast South Stowmarket Michael 19 7.30 Stoke Ash Lopham Scott Aug MP Breakfast Surlingham Train Home Colin 7.30 Tivetshall Clarke E Debenham Thornham Needham Mkt River Green Alder Carr E Hollesley -

7 Manningtree to Flatford and Return

o e o a S a d tr d e e t Recto ry ish Road Hill d Gan Mill Road Warren White Horse Road Wood Barn Hazel Orvi oad d R a Manningtrees to Flatford and return rd o 7 La o f R t n a l e m F a h M ann ingtree R Ded Map of walking routes o ad Braham wood B1070 Spooner's Flatfo Wood rd Road er Sto Riv ur Ba r b ste er e gh The Haugh lch Co Dedham Community Farm ane L Flatford Mill ll E Flatford ll i i s lk B H ffo abergh M s S Su e m N x uff o Ten lk dr B tha reet ing erg n St To Dedham h h ig o Bra H ex lt R Dedham s o s ad E A137 R Riv iv e B1029 e r r S S tour to u r Dedham B O N Forge Street ld River O A C r Judas Gap le o a Ma V w n nin 54 Gates m n gtree d a a S River Stour h t Road d o reet e R r D e r e st t s e e h y c wa h l se c au l o C o C e C h Park Farm T rs H Lane a ope Co l l F le Eas e t L t ill ane H e Great Eastern Main Lin e stle ain Lin a J M upes Greensm C Manningtree astern Manningtree ill H g ill n Great E ll Station i i r H d n e C T o Coxs t S m tation Ro ad a Ea n Ga st C ins La bo ne d h A Q ng Roa East ro u e Lo u v u een n T e g st r a he Ea M h s ad c n w L o ill a h y R H ue D Hill g r il n i He v o l l L e il a May's H th s x Dedham Co Heath Mil Long Road West l H Long Road East ill ad Lawford o Riverview D Church Manningtree B e hall R ar s d g h High School ge ate a C m g h u e L R r Co a n c ne o h a Hil d Road Colchester l e ill v rn Main Li i e r e iv H r D y D r a W t East te e ish a n rav d g u e Hun Cox's ld ters n Wa Cha Gre H se Lawford e d v oa M a Long R y C ich W A137 ea dwa rw ignall B a St t geshall -

East Bergholt Neighbourhood Plan

2015- 2030 East Bergholt, the birthplace and Suffolk home of John Constable Version 1.1 Incorporating Examiner's Modifications July 2016 © 2016 East Bergholt Parish Council. All Rights Reserved. Page 2 of 100 Version 1.1 - July 2016 © 2016 East Bergholt Parish Council. All Rights Reserved. History Draft 1 31 Jul 2015 Ann Skippers First version for review Draft 2 8 Aug 2015 Joan Miller Update housing chapter Draft 3 17 Aug 2015 Paul Ireland Updates agreed at meeting 8 August 2015, Conversion to formatted version & completion of Developing our Plan Draft 3.1 30 Aug 2015 Paul Ireland Add two policies for reinforcing planning rules Draft 4.0 3 Sep 2015 Paul Ireland, Nigel Incorporate initial feedback & finalise Roberts, Ed Housing & Infrastructure policies. Add maps Keeble Draft 4.1 8 Sep 2015 Paul Ireland Incorporate rationale for design statement Draft 4.2 9 Sep 2015 Paul Ireland Feedback from Plan Production Group and include Character Appraisal Draft 5.0 28 Sep 2015 Plan Production Incorporate feedback on policies and text Group from Neighbourhood Plan Committee and Planning Aid England Draft 5.1 5 Oct 2015 Paul Ireland Update maps, diagrams and front picture, add focal point maps and technical updates to policies. Draft 5.2 6 Oct 2015 Paul Ireland Corrections to appendices references Draft 6.0 25 Nov 2015 Plan Production Consider Section 14 comments Group Draft 6.1 14 December Plan Production Consider and incorporate comments from 2015 Group meeting with Babergh on 9 December 2015 Draft 6.2 8 January 2016 Plan Production Consider and incorporate comments relating Group to HRA assessment Version 1.0 5 June 2016 Plan Production Incorporation of all recommendations from Group External Examiner’s Report Version 1.1 20 July 2016 Plan Production Minor corrections identified by Rachel (Referendum) Group Hogger on behalf of Babergh District Council. -

Classes and Activities in Long Melford, Lavenham and Surrounding Areas

Classes and activities in Long Melford, Lavenham and surrounding areas Empowering a Resilient Community to Celebrate Being Physically Active Education-Communication-Marketing Physical Activities All the activities in this booklet have been checked and are appropriate for clients but are also just suggestions unless stated as AOR (please see the key below). Classes can also change frequently, so please contact the venue/instructor listed prior to attending. They will also undertake a health questionnaire with you before you start. There are plenty of other classes or activities locally you might want to try. To find out more about the Active Wellbeing Programme or an activity or class near you, please contact your Physical Activity Advisor below: Nick Pringle Physical Activity Advisor – Babergh 07557 64261 [email protected] Key: Contact Price AOR At own risk (to the best of our knowledge, these activities haven’t got one or more of the following – health screen procedure prior to initial attendance, relevant instructor qualifications or insurance therefore if clients attend it is deemed at own risk) Activities in Long Melford and Lavenham Carpet Bowles Please contact AOR We are a friendly club and meet at 9.45am for a 10am start on a Tuesday morning at Lavenham Village Hall to play Carpet Bowls. You do not need to have played before and most people pick it up very quickly, and tuition is available. It is similar to outdoor bowls as you have to try to get your bowl close to the jack (white ball), but it is played indoors on a long carpet. -

Hadleigh Farm and Country Park Green Infrastructure Case Study the Olympic Mountain Biking Venue for London 2012

Hadleigh Farm and Country Park Green Infrastructure Case Study The Olympic mountain biking venue for London 2012 The creation of an elite mountain biking venue at Hadleigh Farm in Key facts: Essex for the London 2012 Olympic Games provided an opportunity to expand investment in the long-term sporting and recreational Size of the Olympic Mountain facilities within the area. A partnership between landowners, councils Biking Venue: 220 ha (550 acres) and Natural England has capitalised on this opportunity to enhance Combined size of Hadleigh green infrastructure and improve the quality and accessibility of the Farm (Salvation Army) and Country Park (Essex County natural environment for the benefit of local communities and visitors. Council): 512 ha (1,287 acres) The Country Park is one of the largest in Essex and used by Snapshot around 125,000 visitors per year Selection as an Olympic venue provided the catalyst for short The site includes areas and long-term investment designated as a Site of Special Elite and general mountain biking facilities integrated with Scientific Interest, a Special nature conservation objectives Protection Area and Ramsar site (Wetlands of International Legacy facilities for sport and recreation are projected to Importance, especially as increase the number and mix of visitors waterfowl habitat) and a Local Improved accessibility to local green infrastructure has Wildlife Site, and contains promoted healthy and active communities several Scheduled Monuments Construction work on the Olympic course began in July -

The Romantic Sensibility: the Sublime

The Romantic sensibility: the Sublime The sublime is a feeling associated with the strong emotion we feel in front of intense natural phenomena (storms, hurricanes, waterfalls). It generates fear but also attraction. Origin: the term has Latin origins and refers to any literary or artistic form that expresses noble, elevated feelings. Distinction between the beautiful and the sublime: first made by Addison and then by Burke (A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful). The beautiful refers to the qualities of the object (the work of art) and is related to the classical ideas of harmony and perfection, while the sublime is the sensation felt by the perceiver. Different effects of the sublime: minor effects: admiration, respect; major effects: terror, fear. • What causes the sublime: fear of pain, vastness of the ocean, obscurity, powerful sources, the infinite, the unfinished, magnificence and colour (sad, dark colours). The sublime is caused either by what is great and immeasurable or by natural phenomena which underline the frailty of man. • Influence on late 18th century literature: this feeling is central in the works of Romantic poets and Gothic novelists, and is linked to a passion for extreme sensations. • Influence on painting: painters like Turner and Constable wanted to express the sublime in visual art. They were landscape painters and, although in different ways, they emphasized the strength of natural elements and studied the effects of different weather conditions on the landscape. For some aspects, they influenced the French impressionists. Romanticism in English painting • Nature and rural life were key-elements of English Romanticism and they were well represented in landscape painting.