Historians and the Great Revolt, 1857-59* Jitendra Kumar, M.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Regional Directorate of NSS, Lucknow State - Uttar Pradesh

Name of Regional Directorate of NSS, Lucknow State - Uttar Pradesh Regional Director Name Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Number Dr. A.K. Shroti, Regional [email protected] 0522-2337066, 4079533, Regional Directorate of NSS [email protected] 09425166093 Director, NSS 8th Floor, Hall No. [email protected] Lucknow 1, Sector – H, Kendriya Bhawan, Aliganj Lucknow – 226024 Minister Looking after NSS Name Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Number Dr. Dinesh 99-100, Mukhya 0522-2213278, 2238088 Sharma, Dy. Bhawan, Vidhan C.M. and Bhawan, Lucknow Minister, Higher Education Smt. Nilima 1/4, B, Fifth Floor, Katiyar, State Bapu Bhawan, Minister, Lucknow 0522-2235292 Higher Education PS/Secretary Dealing with NSS Name of the Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Secretary with Number State Smt. Monika Garg 64, Naveen [email protected] 0522-2237065 Bhawan,Lucknow Sh. R. Ramesh Bahukhandi First Floor, [email protected] 0522-2238106 Kumar Vidhan Bhawan, Lucknow State NSS Officers Name of the Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline SNO Number Dr. (Higher Education) [email protected] 0522-2213350, 2213089 Anshuma Room No. 38, 2nd [email protected] m 9415408590 li Sharma Floor, Bahukhandiya anshumali.sharma108@g Bhawan, Vidhan mail Bhawan, Lucknow - .com 226001 Programme Coordinator , NSS at University Level Name of the University Name Email ID Telephone/Mobi Programme le/Landline Coordinator Number Dr. Ramveer S. Dr.B.R.A.University,Agra [email protected] 09412167566 Chauhan Dr. Rajesh Kumar Garg Allahabad University, [email protected] 9415613194 Allahabad Shri Umanath Dr.R.M.L. Awadh [email protected] 9415364853 (Registrar) University, Faizabad Dr. -

Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªrobes of Honourº in India

Folklore 112 (2001):23± 45 RESEARCH ARTICLE Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªRobes of Honourº in India Michelle Maskiell and Adrienne Mayor Abstract This article presents seven historical legends of death by Poison Dress that arose in early modern India. The tales revolve around fears of symbolic harm and real contamination aroused by the ancient Iranian-in¯ uenced customs of presenting robes of honour (khilats) to friends and enemies. From 1600 to the early twentieth century, Rajputs, Mughals, British, and other groups in India participated in the development of tales of deadly clothing. Many of the motifs and themes are analogous to Poison Dress legends found in the Bible, Greek myth and Arthurian legend, and to modern versions, but all seven tales display distinc- tively Indian characteristics. The historical settings reveal the cultural assump- tions of the various groups who performed poison khilat legends in India and display the ambiguities embedded in the khilat system for all who performed these tales. Introduction We have gathered seven ª Poison Dressº legends set in early modern India, which feature a poison khilat (Arabic, ª robe of honourº ). These ª Killer Khilatº tales share plots, themes and motifs with the ª Poison Dressº family of folklore, in which victims are killed by contaminated clothing. Because historical legends often crystallise around actual people and events, and re¯ ect contemporary anxieties and the moral dilemmas of the tellers and their audiences, these stories have much to tell historians as well as folklorists. The poison khilat tales are intriguing examples of how recurrent narrative patterns emerge under cultural pressure to reveal fault lines within a given society’s accepted values and social practices. -

Indian National Congress and Eka Movement in Awadh*

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2018): 7.426 Indian National Congress and Eka Movement in Awadh* Amit Kumar Tiwari Research Scholar, Center For Gandhian Thought and Peace Studies, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, Sector- 29, 382029 Abstract: Awadh region has glorious historical background. In ancient India, Awadh region came under KaushalJanapada. According to Hindu mythology, Rama was the king of KaushalJanapada whose capital was Ayodhya which is now in Faizabad district of Utter Pradesh. This area was the heartland of Saltanat kings as well as Mughal kings because of its agriculture production. In later Mughal period, Awadhbecame independent state.Dalhousie conquered Awadh in 1856. And, after British control, a series of peasant’s movement started in different parts of Awadh. After the establishment of Indian National Congress, peasant movements got new dimension. The discourse on peasant movements have been discussed by mainly three school of thoughts in India such as Marxist perspective, nationalist perspective and subaltern perspective. Therefore, this paper is an attempt to understand Eka movement under the umbrella of Indian national Congress. Keywords: Peasant‟s movements, Indian National Congress, KisanSabha, Eka movement *The present paper is a chapter of my M.Phil.dissertation ‘Indian National Congress and Peasant Movements; A Study of Eka Movement in Awadh’ Central University of Gujarat, 2016. I am grateful to the Centre for Gandhian Thought and Peace Studies at Central University of Gujarat. I am also grateful to my supervisor, Mr.SmrutiRanjan Dhal under whom supervision, I conducted my M.Phil. work. I am also thankful to my new supervisor, Dr. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

91 Chapter-I the AWADH REGION Growth and Development Of

91 Chapter-I THE AWADH REGION Growth and Development of Tourism As discussed in the foregoing, the Awadh Region has been attracting pilgrims and devotees from time immemorial (Al Ichin,'70; Younger,'70). The legend of Rama and the Buddha has been a major pull factor, particularly to the holy centres associated with these personalities. Ayodhya stands out boldly on the religious map of India. Classed as one of the seven sacred cities of the Hindus (Saptpuri) it spontaneously acquires a national importance, and hence people have been travelling to this land from far off places to pay their homage to Lord Rama. The sojourn of the Buddha for the major part remained confined to the forest groves of the Tarai in eastern U.P. and some sequestered areas (Dutta and Bajpai,'56). However, none of these places could develop as a regular centre of visitation except Sravasti, in the study area, which was no better than a subdued wilderpess until the late 1960's when it began to be groomed as a Buddhist resort. Pilgrimages are marked by the concept of austerity and simplicity which often come as an antithesis to the concept of modern tourism. The Hindu scheme of Tirthas (pilgrimages) encompasses travel as an essential ingredient but it also discourages developed travel comforts in accommodation and transport and the like, which are an essential part of modern tourism. Thus, it is easy to discover that only the basic and minimum travel facilities were organised by the Hindu missionaries, both enroute and at the pilgrim destination. 92 The dharamshalas, panda homestays, th. -

Stratification and Role of the Elite Muslim Women in the State of Awadh, 1742-1857

Athens Journal of History - Volume 7, Issue 4, October 2021 – Pages 269-294 Stratification and Role of the Elite Muslim Women in the State of Awadh, 1742-1857 By Naumana Kiran This paper focuses on stratification and role of the elite Muslim women in the State of Awadh during the second-half of the eighteenth, and first-half of nineteenth century India. It evaluates the categorization of women associated with the court and the division of political and domestic power among them. It also seeks their economic resources and their contribution in fields of art and architecture. The study finds that the first category of royal women of Awadh, including queen mothers and chief wives, enjoyed a powerful position in the state-matters unlike many other states of the time in India. Besides a high cadre of royal ladies, three more cadres of royal women existed in Awadh’s court with multiple ratios of power and economic resources. Elite women’s input and backing to various genres of art, language and culture resulted in growth of Urdu poetry, prose, drama and music in addition to religious architecture. The paper has been produced on the basis of primary and secondary sources. It includes the historical accounts, written by contemporary historians as well as cultural writings, produced by poets and literary figures of the time, besides letters and other writings of the rulers of Awadh. The writings produced by the British travelers, used in this paper, have further provided an insightful picture and a distinctive perspective. Introduction The study of Muslim women of Awadh, like women of all other areas of India during the 18th and 19th centuries, is a marginalized theme of study in historiography of India. -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh District Majistrate Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) Ganga Vichar Manch Nehru Yuva Kendra Sangathan (NYKS) Name of District Youth Coordinator Mobile Number Landline number of Name of Districts Name of Districts District DM name and Address Telephone District DFO name and Address Mobile no. Name Region Location Mobile no. (DYC) of DYC Kendra 1 Bijnor 9454417570 Bijnor DFO Bijnor(SF) 9453006738 - 01342-262259 Mr. Chandraprakash Chauhan Coordinator-West UP Region Vidurkuti (Bijnore) 9310186745 Director General (over all) Major General Dilawar Singh 011-22446078 [email protected] 2 Muzaffarnagar 9454417574 Muzaffarnagar DFO Muzaffarnagar 9453006658; 0131-2621740 Mr. Raghavendra Singh Coordinator-Kanpur Region,U.P Kanpur,Bithpoor 7007887446 Joint Director (over all) Mr. M.P. Gupta 9811464258 3 Badaun 9415908422 Badaun DFO - Badaun 9453005543; 05832-266098 Ms. Anamika Chaudhary Coordinator-Kashi Region,U.P Allahabad 9415214619 Assistant director (over all) Mr. A.K. Verma 9818796097 Uttar Pradesh State sdnyksuttarpradesh@gm Shahjahanpur 9454417527 Shahjahanpur 4 Mr. Sanjeev Chaurasia Joint Coordinator-Kashi Region,U.P Varanasi 9334028085, 9721280988 Coordinator Shri JPS Negi 8005496699 ail.com 5 Aligarh 9454415313 Aligarh DFO Aligarh 9453006593; 0571-2720076 Mr. Rambahadur Singh Ganga Volunteer- Awadh Region UttarRajghat-Chibramau Pradesh Hardoi 9415175587 Bijnor Sh Sanjeev Kumar 9354980434 01342-255123 6 Hardoi 9454417556 Hardoi DFO Hardoi - Mr. Ashok Sharma Joint Coordinator-West U.P. Region Garhmukteshwar 9634755249;8979328472 Meerut Sh. Ashu Gupta 9027816253 0121-2771352 7 Unnao 9454417561 Unnao DFO-Unnao 9453008179;0515-2829274 Mr. Ashish Sharma Joint Coordinator-West U.P. Region Anupshahr, Narora, RoobhiBhagwanpur 9891971708 Bulandshahar Sh. Shiv Dev Sharma 9968030443 05732-282845 Kanpur Dehat Kanpur Dehat DFO Kanpur Dehat 9453006402; 05111-271553 Hapur (Gaziabad) Sh. -

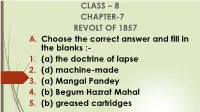

CLASS – 8 CHAPTER-7 REVOLT of 1857 A. Choose the Correct Answer and Fill in the Blanks :- 1

CLASS – 8 CHAPTER-7 REVOLT OF 1857 A. Choose the correct answer and fill in the blanks :- 1. (a) the doctrine of lapse 2. (d) machine-made 3. (a) Mangal Pandey 4. (b) Begum Hazrat Mahal 5. (b) greased cartridges B. Match the columns :- 1. Kanpur — Nana Saheb 2. Bareilly — Khan bahadur khan 3. Delhi — Bhakt Khan 4. Lucknow — Begum Hazrat Mahal 5. Bihar — Kunwar Singh C. Fill in the blanks :- 1. Doctrine of lapse 2. Soldiers 3. Meerut 4. Bahadur Shah 5. Territorial annexation D. State whether true or false. If false, correct the statement. 1. True 2. False – the social reforms introduced by the British were considered as unnecessary interferences by the British in the social customs of Indian society 3. true 4. True 5. True E. Answer the following questions in 10 5.20 words :- 1. What profession did the artisans and craft men turn to when they could no longer make profit from their products ? ANS : the artisans and craftmen were forced to work according to the desire of the servants of the company and in return, received very little remuneration. 2 . Why did the soldiers not want to use the greased cartridges ? ANS : At that time it was believed that the grease used in the cartridges was made from the fat of cows and pigs. Both Hindu and Muslim soldiers refused to use the greased cartridges as it hurt their religious sentiments. 3. Who led the revolt against the British in awadh? Ans: Begum Hazrat Mahal led the revolt against the British in Awadh. 4. -

Federalism & State Reorganization Dr.Shalini Sharma the Idea Of

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Federalism & State Reorganization Dr.Shalini Sharma* The idea of federalism as an organizing principle between different levels of a state is quite old. Greek city states had it. Lichchavi kingdom of northern India in the 6th century BC isa celebrated example of a republican system. In the modern world, this continues to be themost popular system in larger countries like US, Brazil, Mexico and India. In fact, the EuropeanUnion is a recent example of the idea of federalism being implemented at a trans-national levelto leverage its various advantages in the economic sphere. The concept was celebrated by political philosphers like Montesquie as “confederate republic constituted by sovereign city states”. The architect of Indian Constitution, Baba Saheb Ambedkar believed that fora culturally, ethnically and linguistically diverse and heterogeneous country like India, federalism was the „chief mark‟,though with a strong unitary bias. This understanding differed from what Mahatma Gandhi put forward in his speeches which advocated “Village Decentralization”. Hopefully through the establishment of Panchayati System and after 73rd& 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts, this thought of Bapu was also incorporated in our federal system. But with Globalization & Rise of Regional Political Leadership, the face of federal system has constantly changed with time. -

An Historical Re-Reading of Evolving Land-Man Relationship in The

An historical re-reading of evolving land-man relationship in the Princely State Cooch Behar ( 1772-1949): Contextualizing political economy of regional history in perspective A Thesis submitted for the Degtee of Doctor of Philosophy (Arts) of the University ofNorth Bengal Submitted By Smt. Prajnaparamita Sarkar Assistant Professor of History Darjeeling Govt. College Darjeeling Supervisor Dr. Ananda Gopal Ghosh Professor of History Department of History University ofNorth Bengal tttt92 Contents Page Preface 1-11 Glossary lll-Vl Map Vll-Vlll List of Tables IX Introduction 1-41 Chapter -1 An Historical Outline of the Princely State Cooch Behar 42-63 1.1. Cooch Behar State under the Independent Koch Rulers 1.2. Cooch Behar State under the Feudatory Chiefs 1.3. The People ofthe State ofCooch Behar 1.4. The Pre-colonial Social, Economic and Political Structure of the State of Cooch Behar Chapter-2 History of Land Settlements in India: A Regional Perspective 64-105 2.1. Pre- Colonial Land Management System in India 2.2. Land Management System of India under Colonial Rule 2.3 The Land- man relationship oflndia under Colonial Rule Chapter-3 Land Settlements in Cooch Behar: An Overview 106-148 3 .1. Pre-Colonial Land Management System of the Cooch Behar State 3.2. The Colonial Land Management System ofthe Cooch Behar State Chapter-4 Regional Historiography: Political Economy of the Princely State Cooch Behar 149-174 4.1 Regional Historiography, Regional History and (or) Local History 4.2. A Synoptic View on Political Economy 4.3. Political Economy of Cooch Behar State in Pre-colonial and Colonial Period Chapter-S Impact Study of Land Settlements in the Princely State Cooch Behar 175-195 Conclusion I 96-208 Bibliography 209-217 Appendices 218-243 Preface At the out set, let me submit my compulsions and convenience in undertaking this academic exercise what I have attempted to make for nearly a decade. -

The Annexation of Awadh and Its Consequences

THE ANNEXATION OF AWADH AND ITS CONSEQUENCES THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By ARSHAD ALI AZM! Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR DR. S. NURUL HASAN CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITYALIGARH 1973 "^Ou THESIS SECTION ss^r^^^'^'^'^^^^p,^^ Cr^l ^-IC ^ 7 T3028 CONTENTS Preface i I. The Natrabi Administration 1 II. The Annexation 75 III. Establishiaent of the Coiapany's Rule 1856-57 124 IV. Revenue Administration 222 V. Establishment of British Rule 1858-61 286 VI. The Consequences of the Establlshaent of the British Rule 35 o Some Conclusions 400 Api^endix 405 Bibliography 418 £ £ t. X a. s. s. Thtxn is an assumption that before the establishment of British rule, the overwhelming majority of the Indian people depended for their livelihood exclusively on agriculture. This a8sumptl(m has been based mainly on the fact that no direct taxes were Imposed by the Ckyvemment on any branch of Industry or trade and the source of Income of the state was derived almost exclusively from the tax on land. On the other hand the rulers have been accused of not evincing much Interest In protecting the local Industries and markets fjrom foreign competition* The question of landed rights has been engaging the attention of the students of history and a great deal of material has already been published^ but few attempts have been made to scrutlnlss the local records to arrive at a definite conclusion. Similarly, few attempts have been made to study the Impact of the fiscal and Judicial system of the British Oovemmen on the Indian Society.