The Annexation of Awadh and Its Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Regional Directorate of NSS, Lucknow State - Uttar Pradesh

Name of Regional Directorate of NSS, Lucknow State - Uttar Pradesh Regional Director Name Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Number Dr. A.K. Shroti, Regional [email protected] 0522-2337066, 4079533, Regional Directorate of NSS [email protected] 09425166093 Director, NSS 8th Floor, Hall No. [email protected] Lucknow 1, Sector – H, Kendriya Bhawan, Aliganj Lucknow – 226024 Minister Looking after NSS Name Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Number Dr. Dinesh 99-100, Mukhya 0522-2213278, 2238088 Sharma, Dy. Bhawan, Vidhan C.M. and Bhawan, Lucknow Minister, Higher Education Smt. Nilima 1/4, B, Fifth Floor, Katiyar, State Bapu Bhawan, Minister, Lucknow 0522-2235292 Higher Education PS/Secretary Dealing with NSS Name of the Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Secretary with Number State Smt. Monika Garg 64, Naveen [email protected] 0522-2237065 Bhawan,Lucknow Sh. R. Ramesh Bahukhandi First Floor, [email protected] 0522-2238106 Kumar Vidhan Bhawan, Lucknow State NSS Officers Name of the Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline SNO Number Dr. (Higher Education) [email protected] 0522-2213350, 2213089 Anshuma Room No. 38, 2nd [email protected] m 9415408590 li Sharma Floor, Bahukhandiya anshumali.sharma108@g Bhawan, Vidhan mail Bhawan, Lucknow - .com 226001 Programme Coordinator , NSS at University Level Name of the University Name Email ID Telephone/Mobi Programme le/Landline Coordinator Number Dr. Ramveer S. Dr.B.R.A.University,Agra [email protected] 09412167566 Chauhan Dr. Rajesh Kumar Garg Allahabad University, [email protected] 9415613194 Allahabad Shri Umanath Dr.R.M.L. Awadh [email protected] 9415364853 (Registrar) University, Faizabad Dr. -

Ancient Site Sravasti

MANOJ KUMAR SAXENA ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA LUCKNOW CIRCLE The Site The site is located (N27⁰ 31’. 150”; E82⁰ 02’. 504”) on the alluvium flood plains of River Achiravati (Rapti), about 195 km east of Lucknow and 15km district headquarter Sravasti (at Bhinga) of Uttar Pradesh. Historical Background of the Site Sravasti was the capital of the ancient kingdom of Kosala. The earliest references of the city are available in Ramayana and Mahabharata as a prosperous city in the kingdom of Kosala. It is said to have derived its name from a legendary king Sarvasta of solar race who is stated to have founded the city. Therefore, it became ‘Savatthi’ or Sravasti. In the 6th century BC, during the reign of Presenajit, the place rose to fame due to its association with Buddha and Mahavira and became one of the eight holy places of Buddhist pilgrimage. During the days of Buddha its prosperity reached the peak under the powerful ruler of Prasenaji. In the Mahaparinibnana-Sutta Sravasti is mentioned as one of the six important cities where Buddha had a large followers. Buddha is said to have spent 24 or 25 rainy seasons (varshavas) here after his disciple Sudatta Anathapindika built a monastery for him at Jetavana. Historical Background of Excavations The ruins of Sravasti remained forgotten until they were brought to light and identified by Sir Alexander Cunningham in 1863. Subsequently, the site was excavated by several scholars, Marshal (1909-14), K.K. Sinha (1959), Lal Chand Singh (1991-98), Kansai University, Japan and Later by the Excavation Branch Patna in the first decade of this century. -

Research Article

Available Online at http://www.recentscientific.com International Journal of CODEN: IJRSFP (USA) Recent Scientific International Journal of Recent Scientific Research Research Vol. 10, Issue, 11(A), pp. 35764-35767, November, 2019 ISSN: 0976-3031 DOI: 10.24327/IJRSR Research Article SOME MEDICINAL PLANTS TO CURE JAUNDICE AND DIABETES DISEASES AMONG THE RURAL COMMUNITIES OF SHRAVASTI DISTRICT (U.P.) , INDIA Singh, N.K1 and Tripathi, R.B2 1Department of Botany, M.L.K.P.G. College Balrampur (U.P.), India 2Department of Zoology, M.L.K.P.G. College Balrampur (U.P.), India DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24327/ijrsr.2019.1011.4166 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT An ethnobotanical survey was undertaken to collect information from traditional healers on the use Article History: of medicinal plants in rural communities of district Shravasti Uttar Pradesh. The important th Received 4 August, 2019 information on the medicinal plants was obtained from the traditional medicinal people. Present th Received in revised form 25 investigation was carried out for the evaluation on the current status and survey on these medicinal September, 2019 plants. In the study we present 14 species of medicinal plants which are commonly used among the th Accepted 18 October, 2019 rural communities of Shravasti district (U.P.) to cure jaundice and diabetes diseases. This study is th Published online 28 November, 2019 important to preserve the knowledge of medicinal plants used by the rural communities of Shravasti district (U.P.), the survey of the psychopharmacological and literatures of these medicinal plants Key Words: have great pharmacological and ethnomedicinal significance. Medicinal plants, jaundice and diabetes diseases, rural communities of Shravasti. -

Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªrobes of Honourº in India

Folklore 112 (2001):23± 45 RESEARCH ARTICLE Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªRobes of Honourº in India Michelle Maskiell and Adrienne Mayor Abstract This article presents seven historical legends of death by Poison Dress that arose in early modern India. The tales revolve around fears of symbolic harm and real contamination aroused by the ancient Iranian-in¯ uenced customs of presenting robes of honour (khilats) to friends and enemies. From 1600 to the early twentieth century, Rajputs, Mughals, British, and other groups in India participated in the development of tales of deadly clothing. Many of the motifs and themes are analogous to Poison Dress legends found in the Bible, Greek myth and Arthurian legend, and to modern versions, but all seven tales display distinc- tively Indian characteristics. The historical settings reveal the cultural assump- tions of the various groups who performed poison khilat legends in India and display the ambiguities embedded in the khilat system for all who performed these tales. Introduction We have gathered seven ª Poison Dressº legends set in early modern India, which feature a poison khilat (Arabic, ª robe of honourº ). These ª Killer Khilatº tales share plots, themes and motifs with the ª Poison Dressº family of folklore, in which victims are killed by contaminated clothing. Because historical legends often crystallise around actual people and events, and re¯ ect contemporary anxieties and the moral dilemmas of the tellers and their audiences, these stories have much to tell historians as well as folklorists. The poison khilat tales are intriguing examples of how recurrent narrative patterns emerge under cultural pressure to reveal fault lines within a given society’s accepted values and social practices. -

Basic Data Report of Kaliandi- Vihar Exploratory Tube

GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF SHRAVASTI DISTRICT, UTTAR PRADESH By S. MARWAHA Superintending. Hydrogeologist CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 I. INTRODUCTION ..................5 II. CLIMATE & RAINFALL ..................5 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOILS ..................6 IV. HYDROGEOLOGY ..................7 V. GROUND WATER RESOURCES & ESTIMATION ..................11 VI. GROUND WATER QUALITY ..................13 VII. GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT ..................16 VIII. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................17 IX. AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................18 X. AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWA/SGWA ..................18 XI. RECOMMENDATIONS ..................18 TABLES : 1. Land Utilisation of Shravasti district (2008-09) 2. Source-wise area under irrigation (Ha), Shravasti, UP 3. Block-wise population covered by hand pumps, Shravasti, UP 4. Depth to water levels - Shravasti district 5. Water Level Trend Of Hydrograph Stations Of Shravasti District, U.P. 6. Block Wise Ground Water Resources As On 31.3.2009, Shravasti 7. Constituent, Desirable Limit, Permissible Limit Number Of Samples Beyond Permissible Limit & Undesirable Effect Beyond Permissible Limit 8. Chemical Analysis Result Of Water Samples, 2011, Shravasti District, U.P 9. Irrigation Water Class & Number of Samples, Shravasti District, U.P 10. Block wise Ground water Extraction structures, 2009, Shravasti, U.P PLATES : (I) Hydrogeological Map Of Shravasti District, U.P. (II) Depth To Water Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (III) Depth To Water Map (Post-Monsoon, 2012) , Shravasti District, U.P. (IV) Water Level Fluctuation Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012—Post-Monsoon,2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (V) Ground Water Resources, as on 31.3.2009, Shravasti District, U.P. 2 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 1858 ii. -

Statistical Diary, Uttar Pradesh-2020 (English)

ST A TISTICAL DIAR STATISTICAL DIARY UTTAR PRADESH 2020 Y UTT AR PR ADESH 2020 Economic & Statistics Division Economic & Statistics Division State Planning Institute State Planning Institute Planning Department, Uttar Pradesh Planning Department, Uttar Pradesh website-http://updes.up.nic.in website-http://updes.up.nic.in STATISTICAL DIARY UTTAR PRADESH 2020 ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS DIVISION STATE PLANNING INSTITUTE PLANNING DEPARTMENT, UTTAR PRADESH http://updes.up.nic.in OFFICERS & STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION 1. SHRI VIVEK Director Guidance and Supervision 1. SHRI VIKRAMADITYA PANDEY Jt. Director 2. DR(SMT) DIVYA SARIN MEHROTRA Jt. Director 3. SHRI JITENDRA YADAV Dy. Director 3. SMT POONAM Eco. & Stat. Officer 4. SHRI RAJBALI Addl. Stat. Officer (In-charge) Manuscript work 1. Dr. MANJU DIKSHIT Addl. Stat. Officer Scrutiny work 1. SHRI KAUSHLESH KR SHUKLA Addl. Stat. Officer Collection of Data from Local Departments 1. SMT REETA SHRIVASTAVA Addl. Stat. Officer 2. SHRI AWADESH BHARTI Addl. Stat. Officer 3. SHRI SATYENDRA PRASAD TIWARI Addl. Stat. Officer 4. SMT GEETANJALI Addl. Stat. Officer 5. SHRI KAUSHLESH KR SHUKLA Addl. Stat. Officer 6. SMT KIRAN KUMARI Addl. Stat. Officer 7. MS GAYTRI BALA GAUTAM Addl. Stat. Officer 8. SMT KIRAN GUPTA P. V. Operator Graph/Chart, Map & Cover Page Work 1. SHRI SHIV SHANKAR YADAV Chief Artist 2. SHRI RAJENDRA PRASAD MISHRA Senior Artist 3. SHRI SANJAY KUMAR Senior Artist Typing & Other Work 1. SMT NEELIMA TRIPATHI Junior Assistant 2. SMT MALTI Fourth Class CONTENTS S.No. Items Page 1. List of Chapters i 2. List of Tables ii-ix 3. Conversion Factors x 4. Map, Graph/Charts xi-xxiii 5. -

Not No 86 Dt 10 01 2020.Pdf

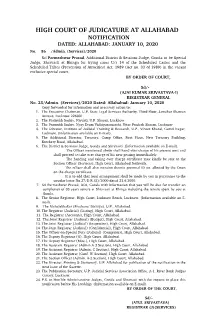

HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT ALLAHABAD NOTIFICATION DATED: ALLAHABAD: JANUARY 10, 2020 No. 86 /Admin. (Services)/2020 Sri Parmeshwar Prasad, Additional District & Sessions Judge, Gonda to be Special Judge, Shravasti at Bhinga for trying cases U/s 14 of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (Act no. 33 of 1989) in the vacant exclusive special court. BY ORDER OF COURT, Sd/- (AJAI KUMAR SRIVASTAVA-I) REGISTRAR GENERAL No. 23/Admin. (Services)/2020 Dated: Allahabad: January 10, 2020 Copy forwarded for information and necessary action to: 1. The Executive Chairman, U.P. State Legal Services Authority, Third Floor, Jawahar Bhawan Annexe, Lucknow-226001. 2. The Pramukh Sachiv, Niyukti, U.P. Shasan, Lucknow 3. The Pramukh Sachiv, Nyay Evam Vidhiparamarshi, Uttar Pradesh Shasan, Lucknow 4. The Director, Institute of Judicial Training & Research, U.P., Vineet Khand, Gomti Nagar, Lucknow. (Information available on E-mail). 5. The Additional Director, Treasury, Camp Office, First Floor, New Treasury Building, Kutchery Road, Allahabad. 6. The District & Sessions Judge, Gonda and Shravasti .(Information available on E-mail). The Officer mentioned above shall hand over charge of his present post and shall proceed to take over charge of his new posting immediatlely. The handing and taking over charge certificate may kindly be sent to the Section Officer (Services), High Court, Allahabad forthwith. The officer shall also mention therein personal ID no. allotted by the Court on the charge certificate. It is to add that local arrangement shall be made by you in pursuance to the circular letter No.27/D.R.(S)/2000 dated 21.6.2000. -

Indian National Congress and Eka Movement in Awadh*

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2018): 7.426 Indian National Congress and Eka Movement in Awadh* Amit Kumar Tiwari Research Scholar, Center For Gandhian Thought and Peace Studies, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, Sector- 29, 382029 Abstract: Awadh region has glorious historical background. In ancient India, Awadh region came under KaushalJanapada. According to Hindu mythology, Rama was the king of KaushalJanapada whose capital was Ayodhya which is now in Faizabad district of Utter Pradesh. This area was the heartland of Saltanat kings as well as Mughal kings because of its agriculture production. In later Mughal period, Awadhbecame independent state.Dalhousie conquered Awadh in 1856. And, after British control, a series of peasant’s movement started in different parts of Awadh. After the establishment of Indian National Congress, peasant movements got new dimension. The discourse on peasant movements have been discussed by mainly three school of thoughts in India such as Marxist perspective, nationalist perspective and subaltern perspective. Therefore, this paper is an attempt to understand Eka movement under the umbrella of Indian national Congress. Keywords: Peasant‟s movements, Indian National Congress, KisanSabha, Eka movement *The present paper is a chapter of my M.Phil.dissertation ‘Indian National Congress and Peasant Movements; A Study of Eka Movement in Awadh’ Central University of Gujarat, 2016. I am grateful to the Centre for Gandhian Thought and Peace Studies at Central University of Gujarat. I am also grateful to my supervisor, Mr.SmrutiRanjan Dhal under whom supervision, I conducted my M.Phil. work. I am also thankful to my new supervisor, Dr. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

Flood Study in Shrawasti District of Uttar Pradesh

International Journal of Scientific & Innovative Research Studies ISSN : 2347-7660 (Print) | ISSN : 2454-1818 (Online) FLOOD STUDY IN SHRAWASTI DISTRICT OF UTTAR PRADESH Dr Prashant Singh] Assistant Professor, Department Of Geography, FAA Government PG College Mahmudabad Sitapur. ABSTRACT Floods are regular phenomena in India. Almost every year floods of varying magnitude affect some or other parts of the country. In 2017 around thousands of people were affected in more than 100 villages of Jamunaha and Hariharpur blocks of Shrawasti district due to flooding in Rapti river. Flood maps can be used when drawing up flood-risk management plans, for preventing flood damages, in land use planning, for providing information on floods, in rescue operations, how frequently do floods happen? And how huge floods can be? It is an important measure for minimising loss of lives and properties and helps the concerned authorities, in prompt and effective response during and after floods. Key words: Floods, Jamunaha, Hariharpur, Shrawasti, Rapti river, Flood Maps. STUDY AREA famous district of eastern Uttar Pradesh. As per 2011 census, total population of the district is 1,117,361 persons out of which 593,897 are males Shrawasti district ( Fig. 1 ) is in the north western and 523,464 are females. The district has having 3 part of Uttar Pradesh covering an area of 1858.20 tehsils, 5 blocks and 536 inhabited villages. Sq. Km. Shrawasti, Uttar Pradesh, India is with According to 2001 census, the district accounted coordinates of 27° 30' 19.3644'' N and 82° 2' 9.5568'' 0.56 % of the State’s population. -

91 Chapter-I the AWADH REGION Growth and Development Of

91 Chapter-I THE AWADH REGION Growth and Development of Tourism As discussed in the foregoing, the Awadh Region has been attracting pilgrims and devotees from time immemorial (Al Ichin,'70; Younger,'70). The legend of Rama and the Buddha has been a major pull factor, particularly to the holy centres associated with these personalities. Ayodhya stands out boldly on the religious map of India. Classed as one of the seven sacred cities of the Hindus (Saptpuri) it spontaneously acquires a national importance, and hence people have been travelling to this land from far off places to pay their homage to Lord Rama. The sojourn of the Buddha for the major part remained confined to the forest groves of the Tarai in eastern U.P. and some sequestered areas (Dutta and Bajpai,'56). However, none of these places could develop as a regular centre of visitation except Sravasti, in the study area, which was no better than a subdued wilderpess until the late 1960's when it began to be groomed as a Buddhist resort. Pilgrimages are marked by the concept of austerity and simplicity which often come as an antithesis to the concept of modern tourism. The Hindu scheme of Tirthas (pilgrimages) encompasses travel as an essential ingredient but it also discourages developed travel comforts in accommodation and transport and the like, which are an essential part of modern tourism. Thus, it is easy to discover that only the basic and minimum travel facilities were organised by the Hindu missionaries, both enroute and at the pilgrim destination. 92 The dharamshalas, panda homestays, th. -

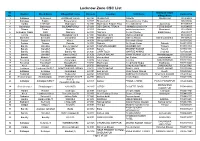

Lucknow Zone CSC List.Xlsx

Lucknow Zone CSC List Sl. Grampanchayat District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No No. Village Name 1 Sultanpur Sultanpur4 JAISINGHPUR(R) 228125 ISHAQPUR DINESH ISHAQPUR 730906408 2 Sultanpur Baldirai Bhawanighar 227815 Bhawanighar Sarvesh Kumar Yadav 896097886 3 Hardoi HARDOI1 Madhoganj 241301 Madhoganj Bilgram Road Devendra Singh Jujuvamau 912559307 4 Balrampur Balrampur BALRAMPUR(U) 271201 DEVI DAYAL TIRAHA HIMANSHU MISHRA TERHI BAZAR 912594555 5 Sitapur Sitapur Hargaon 261121 Hargaon ashok kumar singh Mumtazpur 919283496 6 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 7 Gonda Nawabganj Nawabganj gird 271303 Nawabganj gird Mahmood ahmad 983850691 8 Shravasti Shravasti Jamunaha 271803 MaharooMurtiha Nafees Ahmad MaharooMurtiha 991941625 9 Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 10 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 11 Bareilly Bareilly2 Bareilly Npp(U) 243201 TALPURA BAHERI JASVEER GIR Talpura 7037003700 12 Bareilly Bareilly3 Kyara(R) 243001 Kareilly BRIJESH KUMAR Kareilly 7037081113 13 Bareilly Bareilly5 Bareilly Nn 243003 CHIPI TOLA MAHFUZ AHMAD Chipi tola 7037260356 14 Bareilly Bareilly1 Bareilly Nn(U) 243006 DURGA NAGAR VINAY KUMAR GUPTA Nawada jogiyan 7037769541 15 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 16 Faizabad Faizabad5 Askaranpur 224204 Askaranpur Kanchan ASKARANPUR 7052115061 17 Faizabad Faizabad2 Mosodha(R) 224201 Madhavpur Deepchand Gupta Madhavpur