Response New Trees, New Medicines, New Wars: the Chickasaw Removal* Linda Hogan Chickasaw Nation Writer in Residence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trailword.Pdf

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. _X___ New Submission ____ Amended Submission ======================================================================================================= A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ======================================================================================================= Historic and Historical Archaeological Resources of the Cherokee Trail of Tears ======================================================================================================= B. Associated Historic Contexts ======================================================================================================= (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) See Continuation Sheet ======================================================================================================= C. Form Prepared by ======================================================================================================= -

Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1939 Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Seale, Lea Leslie, "Indian Place-Names in Mississippi." (1939). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7812. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the master^ and doctorfs degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection* Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author* Bibliographical references may be noted3 but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work# A library which borrows this thesis for vise by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions, LOUISIANA. STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 119-a INDIAN PLACE-NAMES IN MISSISSIPPI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisian© State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Lea L # Seale M* A*, Louisiana State University* 1933 1 9 3 9 UMi Number: DP69190 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Destination Oklahoma Rewards Entry Form Destination Oklahoma

2 2011 DESTINATION OKLAHOMA GREEN COUNTRY Play Your Heart Out a letter to TOUR OPERATORS: There’s more to do and see in Oklahoma than you can imagine. And you’ll be greeted TABLEof by some of the friendliest people in the country! Come on, “Play Your Heart Out.” Enjoy Oklahoma hospitality and experience sights and events you won’t find anywhere CONTENTS else! Oklahoma Tourism 2 New to Destination Oklahoma this year: Oklahoma Map 4–5 • Itineraries for your ease in planning, special events listings and a new Rewards Program. Travel across Oklahoma, enter our drawing and win up to $1,000. Details Mileage Charts 5 on page 38. Green Country 6–15 • Enhance your tours by including some exciting events in your planning (see page 36–37) and check out the included websites for even more events (page 36–37). Frontier Country 16–17 We welcome you and your groups…Come on…Play your heart out with us! Great Plains Country 18–20 Kiamichi Country 21 Kaw Lake 22–24 Association GreatPlainsCountry.com Red Carpet Country 25–27 GreenCountryOK.com Arbuckle Country 28–29 Itineraries 30–35 Special Events 36–37 Produced in cooperation with the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. Produced in cooperation with the Oklahoma Tourism KiamichiCountry.com Rewards Program 38 KawLake.com RedCarpetCountry.com Arbuckles.com GREEN COUNTRY Play Your Heart Out 2011 DESTINATION OKLAHOMA 3 OKLAHOMA: Great Destinations 22 4 9 23 1 25 12 26 3 7 24 13 8 27 5 2 28 10 GreenCountryOK.com 11 17 19 21 15 14 6 39 16 PUBLISHER Green Country Marketing Association 34 29 2805 E. -

The People V. Andrew Jackson

The People v. Andrew Jackson Evidence & witness information compiled and organized by Karen Rouse, West Sylvan Middle School, Portland Public Schools, 7 May, 2005. Revised July 2006 Conceptual framework comes from Georgia Vlagos, Naperville Community Unit School District, http://www.ncusd203.org/north/depts/socstudies/vlagos/jackson/jackson.htm. 0 The People v. Jackson Table of Contents Introduction and Procedural Matters.........................................................................................2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................2 Procedural Matters.......................................................................................................................................2 A. Charges................................................................................................................................................................... 2 B. Physical Evidence (list) ......................................................................................................................................... 2 C. Witnesses (list)....................................................................................................................................................... 2 D. Statute..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Witness Statements.....................................................................................................................5 -

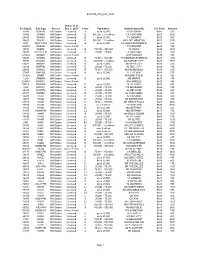

Postcard Data Web Clean Status As of Facility ID. Call Sign Service Oct. 1, 2005 Class Population State/Community Fee Code Amoun

postcard_data_web_clean Status as of Facility ID. Call Sign Service Oct. 1, 2005 Class Population State/Community Fee Code Amount 33080 DDKVIK FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 IA DECORAH 0641 575 13550 DKABN AM Station Licensed B 500,001 - 1.2 million CA CONCORD 0627 3100 60843 DKHOS AM Station Licensed B up to 25,000 TX SONORA 0623 500 35480 DKKSL AM Station Licensed B 500,001 - 1.2 million OR LAKE OSWEGO 0627 3100 2891 DKLPL-FM FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 LA LAKE PROVIDENCE 0641 575 128875 DKPOE AM Station Const. Permit TX MIDLAND 0615 395 35580 DKQRL AM Station Licensed B 150,001 - 500,000 TX WACO 0626 2025 30308 DKTRY-FM FM Station Licensed A 25,001 - 75,000 LA BASTROP 0642 1150 129602 DKUUX AM Station Const. Permit WA PULLMAN 0615 395 50028 DKZRA AM Station Licensed B 75,001 - 150,000 TX DENISON-SHERMAN 0625 1200 70700 DWAGY AM Station Licensed B 1,200,001 - 3 million NC FOREST CITY 0628 4750 63423 DWDEE AM Station Licensed D up to 25,000 MI REED CITY 0635 475 62109 DWFHK AM Station Licensed D 25,001 - 75,000 AL PELL CITY 0636 725 20452 DWKLZ AM Station Licensed B 75,001 - 150,000 MI KALAMAZOO 0625 1200 37060 DWLVO FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 FL LIVE OAK 0641 575 135829 DWMII AM Station Const. Permit MI MANISTIQUE 0615 395 1219 DWQMA AM Station Licensed D up to 25,000 MS MARKS 0635 475 129615 DWQSY AM Station Const. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE CHIKASHSHA POYA TINGBA’ COPING WITH THE DEVALUING OF DIVERSITY IN AMERICA: A STUDY OF THE PERSPECTIVES OF THE CHICKASAW TRIBE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By KAREN GOODNIGHT Norman, Oklahoma 2012 CHIKASHSHA POYA TINGBA’ COPING WITH THE DEVALUING OF DIVERSITY IN AMERICA: A STUDY OF THE PERSPECTIVES OF THE CHICKASAW TRIBE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF INSTRUCTIONAL LEADERSHIP AND ACADEMIC CURRICULUM BY _________________________ Dr. Neil Houser, Chair _________________________ Dr. Frank McQuarrie _________________________ Dr. Stacy Reeder _________________________ Dr. Rockey Robbins _________________________ Dr. Joan Smith © Copyright by KAREN GOODNIGHT 2012 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the endless support, patience, and motivation of my loving husband, Stan, and beautiful children, Kyle, Madie, and Katie. They unselfishly sacrificed our time together as a family so that I could devote many hours to studying, researching, traveling, and writing. Many thanks are due to my in-laws Chris and Molly Goodnight, for their encouragement, prayers, and eagerness to assist with any family needs throughout the years. Chiholloli. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, chair, mentor, and friend, Dr. Neil Houser. His expertise, devotion, and commitment to helping me achieve success with the dissertation was inspirational-“An Kana Chiya’”. This experience will forever be a highlight in my life. I would also like to thank my doctoral committee from the University of Oklahoma, they are each truly genuine and amazing individuals. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Letter from the Acting Secretary of the Interior, Inclosing a Protest of the Governor of the Chickasaw Nation Against Certain Me

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 1-25-1873 Letter from the Acting Secretary of the Interior, inclosing a protest of the Governor of the Chickasaw Nation against certain measures providing for the opening of the Indian Territory to white settlement Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Exec. Doc. No. 141, 42nd Congress, 3rd Sess. (1873) This House Executive Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42n CoNGREss, } ROUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Ex. Doe. 3d Session. { No.141. P ROTEST OF OHIOKASA'l{ N ATIO~. LE':rTER FROM TI-ll!: ACTING SECRETARY OF TilE INTERIOR,, INCLOSING A protest of the governor of the Chickasaw Nation against certain meas ures pro'IJid'i,ng for the opening of the I ndian 'Territory to white settle ment. J ANUARY 25, 1873.-Referreu t o the Committee on I udiau Affairs :wd ordered to be printed. DEP AR'l'MENT OF THE lNTElUOR. lVashington, D. C., January 20, 1873. SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith a copy of a letter, dated the 16th instant, from the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in dosing a communication addressed to the President of the United States by G. -

The Chickasaws and the Mississippi River, 1735-1795

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A RIVER OF CONTINUITY, TRIBUTARIES OF CHANGE: THE CHICKASAWS AND THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER, 1735-1795 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By DUSTIN J. MACK Norman, Oklahoma 2015 A RIVER OF CONTINUITY, TRIBUTARIES OF CHANGE: THE CHICKASAWS AND THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER, 1735-1795 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY __________________________ Dr. Joshua Piker, Chair __________________________ Dr. David Wrobel __________________________ Dr. Catherine E. Kelly __________________________ Dr. Miriam Gross __________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood © Copyright by DUSTIN J. MACK 2015 All Rights Reserved. For Chelsey ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not have been completed without the help of several individuals and institutions. I want to thank my advisor Josh Piker and my entire committee David Wrobel, Catherine Kelly, Miriam Gross, and Patrick Livingood for the time and effort they have invested. The OU History Department has molded me into a historian and made much of this research possible in the form of a Morgan Dissertation Fellowship. For both I am grateful. A grant from the Phillips Fund for Native American Research of the American Philosophical Society facilitated this endeavor, as did a Newberry Consortium in American Indian Studies Graduate Student Fellowship. A Bullard Dissertation Completion Award from the OU Graduate College provided financial support to see this project to fruition. A special thank you goes out to Laurie Scrivener and Jacquelyn Reese Slater at the OU Libraries, Clinton Bagley at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Christina Smith at the Natchez Trace Parkway, and Charles Nelson at the Tennessee State Library and Archives. -

Attachment J FY 2001 AM and FM Radio Regulatory Fees 1

Attachment J FY 2001 AM and FM Radio Regulatory Fees Call Sign Service Class City State City Pop Fee Fee Call Sign Service Class City State City Pop Fee Fee Code Code KAAA AM C Kingman AZ 29,242 $350 0130 KAFF AM D Flagstaff AZ 65,742 $700 0137 KAAB AM D Batesville AR 28,518 $475 0136 KAFF-FM FM C Flagstaff AZ 98,032 $1,375 0149 KAAK FM C1 Great Falls MT 76,022 $1,375 0149 KAFN FM A Gould AR 10,060 $350 0141 KAAM AM B Garland TX 3,451,853 $3,750 0128 KAFX-FM FM C1 Diboll TX 122,604 $1,375 0149 KAAN AM D Bethany MO 17,564 $300 0135 KAFY AM B Bakersfield CA 376,447 $1,450 0126 KAAN-FM FM C2 Bethany MO 11,313 $450 0147 KAGB FM C Waimea HI 47,724 $850 0148 KAAP FM A Rock Island WA 54,425 $900 0143 KAGC AM D Bryan TX 6,293 $300 0135 KAAQ FM C1 Alliance NE 20,015 $850 0148 KAGE AM D Winona MN 45,064 $475 0136 KAAR FM C1 Butte MT 39,768 $850 0148 KAGE-FM FM C3 Winona MN 50,021 $900 0143 KAAT FM B1 Oakhurst CA 26,167 $675 0142 KAGG FM C2 Madisonville TX 127,536 $2,050 0150 KAAY AM A Little Rock AR 500,316 $2,850 0121 KAGH AM D Crossett AR 14,817 $300 0135 KABC AM B Los Angeles CA 10,596,964 $3,750 0128 KAGH-FM FM A Crossett AR 14,106 $350 0141 KABG FM C Los Alamos NM 232,726 $2,050 0150 KAGI AM D Grants Pass OR 69,381 $700 0137 KABI AM D Abilene KS 12,466 $300 0135 KAGL FM C3 El Dorado AR 39,855 $675 0142 KABK-FM FM C2 Augusta AR 53,142 $1,375 0149 KAGM FM A Strasburg CO 3,310 $350 0141 KABL AM B Oakland CA 3,534,188 $3,750 0128 KAGO AM B Klamath Falls OR 48,888 $675 0124 KABN AM A Long Island AK 59,852 $1,375 0119 KAGO-FM FM C1 Klamath Falls -

013 Chickasaw Times January 2007.Pdf

ChickasawOfficial Timespublication of the Chickasaw Nation Vol. XXXXI1 No. 1 January 2007 Ada, Oklahoma Mel Gibson movie featuring Native actors premieres in Chickasaw Nation Tribe hosts Apocalypto special benefit at Riverwind GOLDSBY, Okla. - Proceeds Proceeds from the special to cast the film with only indig- from a benefit event and preview benefit event will go to the enous actors. screening of the new Mel Gib- Mayan People of Mexico, the “It is very important to note son film Apocalypto hosted by Oklahoma Chapter of the Lupus that Mr. Gibson has gone to the Chickasaw Nation will be Foundation of America Inc., great lengths to cast indigenous donated to the Mayan people of Indian Health Care Resource people in this film,” said Gov. Mexico and several Oklahoma Center of Tulsa and Oklahoma Anoatubby. “This not only helps organizations. City Indian Clinic. make the film more realistic, it The December 1 screening “This event provides an op- serves as an inspiration to Native at the tribe’s Riverwind Casino portunity to support a number American actors who aspire to south of Norman prior to the of organizations that are doing perform relevant roles in the film film’s Dec. 8 general release great work,” said Gov. Bill industry.” attracted a number of corporate Anoatubby. “We are enjoying Rudy Youngblood, who plays sponsors who donated a total of success in our business ventures the lead role of Jaguar Paw, is $150,000. and we feel it is very important of Comanche, Cree and Yaqui More than $50,000 in addi- to express our appreciation to heritage. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “PEOPLE TO OUR SELVES”: CHICKASAW DIPLOMACY AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By DANIEL FLAHERTY Norman, Oklahoma 2012 “PEOPLE TO OUR SELVES”: CHICKASAW DIPLOMACY AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY Dr. Joshua Piker, Chair Dr. Fay A. Yarbrough Dr. Terry Rugeley Dr. R. Warren Metcalf Dr. Robert Rundstrom © Copyright by DANIEL FLAHERTY 2012 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any scholarly endeavor, I certainly could not have accomplished this effort alone. Two early influences in my academic career, Ed Crapol and James Axtell, provided me with a love and foundation in the unique methodologies I combine in this dissertation. The idea for this dissertation was born in Robert Shalhope’s seminar in Fall 2006. Dr. Shalhope’s avuncular disposition provided an early litmus test in which to investigate the significance of Native Americans’ understanding of and interaction with the republican experiment that is the United States. His early encouragement gave me the confidence to investigate further. The choice of the Chickasaws as a subject of study is due thanks to a friendly suggestion from Matt Despain. To the members of my committee—during both the exam and dissertation phases—I owe a great deal. Fay Yarbrough has offered thoughtful criticism and consistent encouragement since she first became involved with my work five years ago.