The Translation of Board Games' Rules of Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

THUNDERBIRDS Written by Peter Hewitt, William Osborne & Michael

THUNDERBIRDS Written by Peter Hewitt, William Osborne & Michael McCullers Animated scenes of the Thunderbirds on various rescues begin to play as some of the cast and crew names show up. NARRATOR From a secret island in the South Pacific, the courageous Tracy family run an organization called International Rescue. When disaster strikes, anywhere in the world, they are always first on the scene. They go by the name they gave their incredible machines, the Thunderbirds. (Counts down numbers and shows corresponding Thunderbirds) Five, four, three, two, one. Thunderbirds are go! Cuts to live action, Alan Tracy is looking out a school window. But in this family of heroes, there is one son left behind. TEACHER So, gentlemen, we all know that A2 plus B2 equals... C2, that's right. But what happens when we bring in Leonardo Da Vinci's E, F and... (Teacher notices Alan looking out window and not paying attention to the lesson) Mr. Tracy! FERMAT Alan. Alan! Alan's head jerks back from the window and to the teacher who is now standing in front of him. TEACHER How kind of you to come back from outer space, Alan. I trust re-entry wasn't too rough? (Chuckles sarcastically and continues sounding even more annoyed) Here on Earth we've been discussing the Pythagorean theorem. Did any of that happen to sink in? ALAN TRACY I was just... TEACHER Apparently not (she picks up his notebook which he has been doodling in) "Thunderbirds are go." Well, I hope you aren't going anywhere special over spring break, Alan. -

Download the Digital Booklet

ORIGINAL TELEVISION SOUNDTRACK A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION MUSIC BY BARRY GRAY Calling International Rescue... Palm Treesflutterandthesoundofdistantcrashingwaves echoaroundaluxuriouslookinghouse.Suddenlyalow gravellyhumemergesfromaswimmingpoolasitslides aside,revealingancavernoushangerbelow.Muffled automatedsoundsecho,beforeanalmightyroarfollowedby thelightning-fastblurofarocketasitshootsskyward.Thisis Thunderbird1,high-speedreconnaissance craft,pilotedbyScottTracy. Momentsago,Scott’sbrotherJohn radioed-inadistresscallfromThunderbird5, amannedorbitalsatellite.Alifeis indangerwithallhopelost,except foronepossibility:International Rescue.JeffTracy,theboys’father assessesthesituationandduly deployshissonsintoaction. AsThunderbird1propelsitself towardsthedangerzone(now inhorizontalflight),itsfellowcraft Thunderbird2isreadiedforlaunch.This giantgreentransporterstandsontop ofaconveyer-beltofsixPods,each containingadifferentarrayoffantastic rescueequipment.WiththenecessaryPod selected,VirgilTracy(joinedbybrothers AlanandGordon)taxisthehugevehicleto thelaunchramp,whichraisesthecraftto40 degreesbeforeittooblastsskywards.International Rescueareontheirway,Thunderbirdsarego! Inspiredbythisdramaticevent,forhisnexttelevisionseriesGerry Approaching Danger Zone... Andersonenvisionedanorganisationpreparedforsucheventualities IntheAutumnof1963,writerandproducer -

2006 November Family Room Schedule

NOVEMBER 2006 PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE FAMILY ROOM Time 10/30/06 - Mon 10/31/06 - Tue 11/01/06 - Wed 11/02/06 - Thu 11/03/06 - Fri 11/04/06 - Sat 11/05/06 - Sun Time THE LIVING FOREST FLIPPER 6:00 AM CONT'D (4:50 AM) DARK HORSE KAYLA CONT'D (5:45 AM) RADIO FLYER 6:00 AM TV-PG CONT'D (5:40 AM) CONT'D (5:40 AM) TV-G CONT'D (5:30 AM) FLIPPER UFO A DOLPHIN IN TIME 6:30 AM A QUESTION OF PRIORITIES 6:15 AM 6:30 AM 6:15 AM G 7:00 AM PG MAGIC OF THE GOLDEN BEAR: GOLDY III 7:00 AM TRADING MOM TV-PG TV-PG 6:40 AM TV-PG THE THUNDERBIRDS THE THUNDERBIRDS THE THUNDERBIRDS 7:30 AM 7:05 AM TRAPPED IN THE SKY PIT OR PERIL SUN PROBE 7:30 AM 7:20 AM 7:20 AM 7:25 AM 8:00 AM 8:00 AM TV-G PG TV-PG TV-PG TV-PG FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE FUGITIVE (1) UFO THE THUNDERBIRDS UFO 8:30 AM 8:30 AM STOLEN SUMMER THE RESPONSIBILITY SEAT CITY OF FIRE COURT MARTIAL 8:30 AM TV-G 8:15 AM 8:15 AM 8:25 AM 8:15 AM FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE FUGITIVE (2) 9:00 AM 8:55 AM TV-PG TV-Y7-FV 9:00 AM TV-G OLD SETTLERTV-PG HAMMERBOY UFO 9:30 AM THE LIVING FOREST TV-G 9:05 AM THE SQUARE TRIANGLE 9:05 AM 9:30 AM FLIPPER MOST EXPENSIVE SARDINE IN THE WORLD 9:20 AM 9:50 AM 9:20 AM 10:00 AM TV-G TV-G 10:00 AM FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE SEAL 10:15 AM TV-G LIL ABNER TV-G FLIPPER FLIPPER DOLPHINS DON'T SLEEP THE FIRING LINE (1) 10:30 AM PG 10:30 AM 10:10 AM 10:20 AM 10:30 AM TV-PG DARK HORSE TV-G TV-G FLIPPER FLIPPER THE THUNDERBIRDS AUNT MARTHA THE FIRING LINE (2) 11:00 AM OPERATION CRASH DIVE 10:40 AM 11:00 AM 10:50 AM 11:00 AM 10:45 AM TV-PG-V TV-PG THE THUNDERBIRDS 11:30 AM TV-PG KAYLA SUN PROBE 11:30 -

Thunderbirds ™ and © ITC Entertainment Group Limited 1964, 1999 and 2017

THE COMIC COLLECTION A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION TM CREATED ESPECIALLY FOR ROBIN Happy Christmas Bro. Hope this brings back some memories! Thunderbirds ™ and © ITC Entertainment Group Limited 1964, 1999 and 2017. Licensed by ITV Ventures Limited. All rights reserved. This edition is produced under license by Signature Gifts Ltd, Signature House, 23 Vaughan Road, Harpenden, AL5 4EL. Printed and bound in the UK. GDTEST0123456789 THE COMIC COLLECTION A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION TM CMYK: Black=10c10m10y100k, Yellow=100y or Pantone: Pantone Black, PantoneYellow Use outline logo on dark backgronds CONTENTS THUNDERBIRD 2 TECHNICAL DATA . P68 Artist: Graham Bleathman INTRODUCTION . P4 THE SPACE CANNON . P70 Artist: Frank Bellamy THE EARTHQUAKE MAKER . P6 THE OLYMPIC PLOT . P76 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy VISITOR FROM SPACE . P18 DEVIL’S CRAG . P88 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy THE ANTARCTIC MENACE . P34 THE EIFFEL TOWER DEMOLITION . P96 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy BRAINS IS DEAD . P48 SPECIFICATIONS OF THUNDERBIRD 3 . P104 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Graham Bleathman THUNDERBIRD 1 TECHNICAL DATA . P64 LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 3 . P106 Artist: Graham Bleathman Artist: Graham Bleathman LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 1 . P66 LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 4 . P107 Artist: Graham Bleathman Artist: Graham Bleathman LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 2 . P67 SPECIFICATIONS OF THUNDERBIRD 4 . P108 Artist: Graham Bleathman Artist: Graham Bleathman THE NUCLEAR THREAT . P110 CHAIN REACTION . P186 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy HAWAIIAN LOBSTER MENACE . .P120 THE BIG BANG . P202 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: John Cooper THE TIME MACHINE . P132 THE MINI MOON . P210 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: John Cooper THE ZOO SHIP . P144 THE SECRETS OF FAB 1 . -

THUNDERBIRDS VF - KIT 18 THUNDERBIRDS Thunderbirds Est Un Jeu Coopératif Pour 2 À 4 Joueurs À Partir De 10 Ans

THUNDERBIRDS VF - KIT 18 THUNDERBIRDS Thunderbirds est un jeu coopératif pour 2 à 4 joueurs à partir de 10 ans. INTRODUCTION Dans Thunderbirds, vous et vos compagnons de jeu prenez les rênes de la Sécurité Internationale, une organisation secrête dont l’objet est d’opérer des missions de secours à travers le globe, quand tous les autres moyens ont failli. Cependant, votre adversaire, le terrible criminel connu sous le nom de «the Hood», tente de provoquer de terribles désastres afin de d’essayer de découvrir vos secrets. Si vous pouvez rassembler assez de courage, de volonté, d’ingéniosité, d’intelligence et de compétences techniques, vous pourrez déjouer les plans du Hood et gagner la partie. Mais si le Hood parvient à déclencher l’une de ses catastrophes, ou bien si vous échouez à remplir une mission dans le temps impartis, la sécurité internationale aura échouée et vous perdrez la partie. MATÉRIEL • Un plateau de jeu, • 103 cartes, • 4 cartes Aides de jeu • 6 cartes Personnage • 18 cartes F.A.B. • 28 cartes Plan du Hood (20 catastrophes et 8 évène- ments) • 47 cartes Mission • 30 pions Bonus (6 de chaque qui représente le courage, la volonté, l’intelligence, l’ingéniosité et la compétence tech- nique) • 6 figurines (Thunderbirds 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 et FAB 1) • 10 mini-véhicules (embarqués) • 6 figurines Personnage, Scott (bleu), Virgil (vert), Alan (orange), Gordon (jaune), John (gris) et Lady Penelope (rose) • 1 figurine Hood, • 2 dés de sauvetage OBJECTIF DU JEU L’objectif du jeu est de contrecarrer les plans du Hood (et ses catastrophes) tout en réussissant des missions de secours tout autour du globe (avant que le temps ne manque). -

Los Charlatanes

España vuelve a ir bien… regresan los gestores culturales MÚSICA, HUMOR, PICANTE Teatro del Astillero cumple en 2020 el vigésimo quinto aniversario de su nacimiento como la única compañía formada únicamente por autores, así como espacio acotado para la reflexión, incitación, ensayo y búsqueda de nuevos recursos para la textualidad dramática. A partir de 1995 Teatro del Astillero inició un camino en el que el compromiso se asumió como artístico y la libertad formal en la escritura teatral se buscó desterrando el estilo individual para encontrar la forma propia de cada obra. Para Teatro del Astillero escribir textos es como construir artefactos hechos de materiales tan pesados como el hierro pero que pueden flotar como barcos y arribar a puertos lejanos. Y un artefacto, como reconoce la RAE, es una obra mecánica hecha con arte. España vuelve a ir bien… regresan los gestores culturales Los charlatanes La colonia de pioneros humanos en Marte sufre la cruel dictadura de los gemelos Hynkel y Napaloni, quienes desean imponer una nueva religión: el Capislamismo, así como obligan a sus hermanos a realizar trabajos en prácticas eternas y a convertirse en emprendedores por decreto. El caos en Marte ha desembocado en el colectivismo por pillaje, la recolección errante y los siete pecados capitales como diaria costumbre. Por este motivo, dos valientes marcianos, el capitán Scarlett y Lady Penélope, huyen del planeta rojo con el encargo de entregar un mensaje de socorro a sus hermanos terrestres camuflándose en la Tierra como gestores culturales. Los THUNDERBIRDS es una serie de televisión inglesa basada en supermarionetas de ciencia ficción y aventura para niños creada por AP Films de Gerry Anderson. -

Thunderbirds Are Go Sticker Activity Free

FREE THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO STICKER ACTIVITY PDF Simon & Schuster Uk | 16 pages | 27 Aug 2015 | Simon & Schuster Ltd | 9781471124983 | English | London, United Kingdom Thunderbirds Are Go Sticker Activity 2 by Simon & Schuster UK | Waterstones No fee was accepted by KIWIreviews or the reviewers themselves - these are genuine, unpaid consumer reviews. Available: April Thunderbirds Are Go! From a hidden island base in the South Pacific, the five Tracy brothers pilot remarkable, cutting-edge Thunderbird vehicles from the depths of the oceans to the highest reaches of space, all for one purpose: to help those in need. This official Thunderbirds Are Go bumper sticker and activity book is filled with puzzles, stickers and activities to entertain any budding International Rescue recruit. Check out Hachette online. Everyone is welcome to post a review. You will need to Join up or log in to post yours. We went through all the pages from start to finish so he and I could get an idea of the contents and I could also be sure that he knew how to approach the puzzles, but I need not have been concerned. He is already a capable reader and was able to work out the preliminary instructions for each one; in fact, he assured me that he could not wait to get started. The book has a mixture of activities: stickers to complete puzzles or stories; stickers to just have fun with while decorating full page illustrations; word find, Sudoku, code cracking, line drawings Thunderbirds are Go Sticker Activity colour, and quizzes. Some are quite easy. He chose to Thunderbirds are Go Sticker Activity with one of the Thunderbirds are Go Sticker Activity and completed it in under a minute. -

1 the Barry Gray Centenary Concert

The Barry Gray Centenary Concert 8th November 2008 The Royal Festival Hall Barry Gray Centenary Concert By Theo de Klerk Sunday 9th I flew back home after attending the Barry Gray Centenary Concert in the Royal Festival Hall on the south bank of the Thames in London the evening before. I had had a fantastic night – the first performance where Thunderbirds roared from the orchestra live since the unbeatable “Filmharmonic ‘78” concert by Barry Gray himself. It was so long overdue! I got goose bumps hearing the Thunderbirds incidentals and Zero-X taking off. So why did I mark the concert with a 7 out of 10 instead of a 9 out of 10 I wondered. And then it occurred to me: I was there both as an admirer of Barry Gray’s work but also as a seasoned concert audience member. A fan’s verdict So let’s start with the 9 out of 10. The concert event was long overdue and may not be repeated for many years given the problems to organize such a big happening. The Philharmonia Orchestra and a group of soloists and vocalists had to be booked, the Hall secured. Sound, light, publicity – it was all done by a few people, partly as labour of love, and they pulled it off. It all happened because Katie Ford noticed that 2008 was Barry’s 100th birthday and it should not go by unnoticed. Together with her friend Ralph Titterton they were in an ideal position to provide the Barry Gray scores and François Evans eagerly wanted to conduct the orchestra and Crispin Merrell to play the piano. -

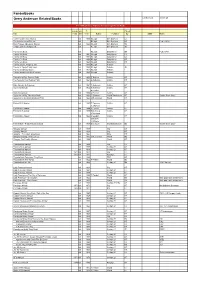

Fanderbooks Gerry Anderson Related Books List Revised: 27-Oct-08

FanderBooks Gerry Anderson Related Books List Revised: 27-Oct-08 Pre-1990 UK Gerry Anderson Annuals/Large Format Books Annual p/b © Check Title Year† h/b Year Author Publisher By ISBN ** Notes Twizzle's Adventure Stories h/b 1958 R.Leigh Birn Brothers AT The Adventures of Twizzle h/b R.Leigh Birn Brothers AT Publ. 1959? More Twizzle Adventure Stories h/b 1960 R.Leigh Birn Brothers TN Twizzle and the Hungry Cat p/b R.leigh Birn Brothers JB Torchy Gift Book h/b R.Leigh Daily Mirror SB Publ. 1960 Torchy Gift Book h/b 1961 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1962 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1963 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1964 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy and the Magic Beam h/b 1960 R.Leigh Pelham - Torchy in Topsy-Turvy Land h/b 1960 R.Leigh Pelham JB Torchy and Bossy Boots h/b 1961 R.Leigh Pelham - Torchy and his Two Best Friends h/b 1962 R.Leigh Pelham - Television's Four Feather Falls h/b 1960 S.Thamm Collins AT Tex Tucker's Four Feather Falls h/b 1961 S.Anderson Collins AT Mike Mercury in Supercar h/b 1961 S.Anderson Collins AT Supercar Annual h/b 1962 S.Anderson Collins AT & E.Eden Supercar Annual h/b 1963 A.Fennell Collins AT Supercar - A Big Television Book h/b 1962 G.Sherman World Distributors AT Golden Book Story Supercar on the Black Diamond Trail h/b 1965 J.W.Jennison World AT Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1963 D.Spooner Collins AT & J.Hynam Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1964 A.Fennell Collins AT Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1965 D.Motton & Collins AT J.Dennison Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1966 S.Goodall, -

Entertainment Memorabilia, 3 July 2013, Knightsbridge, London

Bonhams Montpelier Street Knightsbridge London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax 20771 Entertainment Memorabilia, Entertainment 3 July 2013, 2013, 3 July Knightsbridge, London Knightsbridge, Entertainment Memorabilia Wednesday 3 July 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London International Auctioneers and Valuers – bonhams.com © 1967 Danjaq, LLC. and United Artists Corporation. All Rights reserved courtesy of Rex Features. Entertainment Memorabilia Wednesday 3 July 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services The following symbol is used Montpelier Street Director Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm to denote that VAT is due on the hammer price and buyer’s Knightsbridge Stephanie Connell +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 premium London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see back of catalogue † VAT 20% on hammer price for important notice to bidders and buyer’s premium Viewing Senior Specialist Sunday 30 June Katherine Williams Illustrations * VAT on imported items at 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 Front cover: Lot 236 a preferential rate of 5% on Monday 1 July [email protected] Back cover: Lot 109 hammer price and the prevailing 9am to 4.30pm Inside front cover: Lot 97 rate on buyer’s premium Consultant Specialist Inside back cover: Lot 179 Tuesday 2 July W These lots will be removed to Stephen Maycock 9am to 4.30pm Bonhams Park Royal Warehouse Wednesday 3 July +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 after the sale. Please read the 9am to 11am [email protected] sale information page for more details. -

Beam Aboard the Star Trektm Set Tour!

Let’s roll, Kato! Spring 2019 No. 4 $8.95 The Green Hornet in Hollywood Thunderbirds Are GO! Creature Creator RAY HARRYHAUSEN SAM J. JONES Brings The Spirit to Life Saturday Morning’s 8 4 5 TM 3 0 0 8 5 Beam Aboard the Star Trek Set Tour! 6 2 Martin Pasko • Andy Mangels • Scott Saavedra • and the Oddball World of Scott Shaw! 8 1 Shazam! TM & © DC Comics, a division of Warner Bros. Green Hornet © The Green Hornet, Inc. Thunderbirds © ITV Studios. The Spirit © Will Eisner Studios, Inc. All Rights Reserved. The crazy cool culture we grew up with Columns and Special Departments Features 3 2 CONTENTS Martin Pasko’s Retrotorial Issue #4 | Spring 2019 Pesky Perspective The Green Hornet in 11 3 Hollywood RetroFad 49 King Tut 12 Retro Interview 29 Jan and Dean’s Dean Torrence Retro Collectibles Shazam! Seventies 15 Merchandise Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Mornings 36 Shazam! Too Much TV Quiz 15 38 65 Retro Interview Retro Travel 41 The Spirit’s Sam Jones Star Trek Set Tour – Ticonderoga, New York 41 Retro Television 71 Thunderbirds Are Still Go! Super Collector The Road to Harveyana, by 49 Jonathan Sternfeld Ernest Farino’s Retro Fantasmagoria 78 Ray Harryhausen: The Man RetroFanmail Behind the Monsters 38 80 59 59 ReJECTED The Oddball World of RetroFan fantasy cover by Scott Shaw! Scott Saavedra Pacific Ocean Park RetroFan™ #4, Spring 2019. Published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. Editorial Office: RetroFan, c/o Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief, 112 Fairmount Way, New Bern, NC 28562.