The Lesser Nobility and the French Reformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

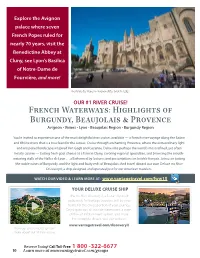

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

Burgundy Beaujolais

The University of Kentucky Alumni Association Springtime in Provence Burgundy ◆ Beaujolais Cruising the Rhône and Saône Rivers aboard the Deluxe Small River Ship Amadeus Provence May 15 to 23, 2019 RESERVE BY SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 SAVE $2000 PER COUPLE Dear Alumni & Friends: We welcome all alumni, friends and family on this nine-day French sojourn. Visit Provence and the wine regions of Burgundy and Beaujolais en printemps (in springtime), a radiant time of year, when woodland hillsides are awash with the delicately mottled hues of an impressionist’s palette and the region’s famous flora is vibrant throughout the enchanting French countryside. Cruise for seven nights from Provençal Arles to historic Lyon along the fabled Rivers Rhône and Saône aboard the deluxe Amadeus Provence. During your intimate small ship cruise, dock in the heart of each port town and visit six UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the Roman city of Orange, the medieval papal palace of Avignon and the wonderfully preserved Roman amphitheater in Arles. Tour the legendary 15th- century Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, famous for its intricate and colorful tiled roof, and picturesque Lyon, France’s gastronomique gateway. Enjoy an excursion to the Beaujolais vineyards for a private tour, world-class piano concert and wine tasting at the Château Montmelas, guided by the châtelaine, and visit the Burgundy region for an exclusive tour of Château de Rully, a medieval fortress that has belonged to the family of your guide, Count de Ternay, since the 12th century. A perennial favorite, this exclusive travel program is the quintessential Provençal experience and an excellent value featuring a comprehensive itinerary through the south of France in full bloom with springtime splendor. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

Relatives and Miles a Regional Approach to the Social Relations of the Lesser Nobility in the County of Somogy in the Eighteenth Century

IS TVAN M. SZIJART6 Relatives and Miles A Regional Approach to the Social Relations of the Lesser Nobility in the County of Somogy in the Eighteenth Century ABSTRACT Through seven socio-economic criteria the author establishes three characteristic Ievels of the lesser nobility of Co. Somogy in the eighteenth century, than takes samples consisting of three families from them. The analysis is based on the assumption that the geographical extent of social relations is rejlected by the network of places where these families brought their wivesfrom or married offtheir daughters to. Theconclusion of this regional approach to the social relations ofthe lesser nobility is that the typical geographical sphere of life was the narrow neighbourhood of their village for the petty nobility, while for the well-to-dogentry it was approximately the county and for the wealthy andinjluential leading families it was a larger geographical unit. While at the time of its foundation in the early eleventh century the system of counties (comitatus, wirmegye) in the kingdom of Hungary was a bulwark of royal power, from the end of the thirteenth century it had been gradually transformed into the organ of the local self-government of the nobility. In the eighteenth century the nobility exercised the bul.k of administration, certain judicial and local legislative power througb the organization of the county. The head of the county was thefoispdn (supremus comes) appointed by the king, usually a lay or ecclesiastical lord absent from the county, while the actual self-go vernment of the county was directcd by the elected alispdn (vicecomes). -

Eurostar, the High-Speed Passenger Rail Service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels And, Today, Uniquely, to Cannes

YOU R JOU RN EY LONDON TO CANNES . THE DAVINCI ONLYCODEIN cinemas . LONDON WATERLOO INTERNATIONAL Welcome to Eurostar, the high-speed passenger rail service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels and, today, uniquely, to Cannes . Eurostar first began services in 1994 and has since become the air/rail market leader on the London-Paris and London-Brussels routes, offering a fast and seamless travel experience. A Eurostar train is around a quarter of a mile long, and carries up to 750 passengers, the equivalent of twojumbojets. 09 :40 Departure from London Waterloo station. The first part of ourjourney runs through South-East London following the classic domestic line out of the capital. 10:00 KENT REGION Kent is the region running from South-East London to the white cliffs of Dover on the south-eastern coast, where the Channel Tunnel begins. The beautiful rolling countryside and fertile lands of the region have been the backdrop for many historical moments. It was here in 55BC that Julius Caesar landed and uttered the famous words "Veni, vidi, vici" (1 came, l saw, 1 conquered). King Henry VIII first met wife number one, Anne of Cleaves, here, and his chieffruiterer planted the first apple and cherry trees, giving Kent the title of the 'Garden ofEngland'. Kent has also served as the setting for many films such as A Room with a View, The Secret Garden, Young Sherlock Holmes and Hamlet. 10:09 Fawkham Junction . This is the moment we change over to the high-speed line. From now on Eurostar can travel at a top speed of 186mph (300km/h). -

Investigative Leads for Use in the Ensuing Cold War

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 24, June 22, 1982 were made to preserve strains of the Nazi experiment Investigative Leads for use in the ensuing Cold War. Major branches of the Order There are four primary branches of the original crusading Hospitaler Order in existence today: The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM) was rechartered by the Papacy in 1815. When Napoleon conquered the Hospitaler's island base of Malta in 1798, Hospitaler knights Czar Paul I of Russia assumed protectorship of the Order. After his assassination, his son, Alexander I, of a new dark age relinquished this office to the Papacy. The SMOM remains affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, though it has been condemned by Popes John XXIII by Scott Thompson and Paul VI. It is the only branch with true sovereignty, and has diplomatic immunity for its emissaries and Investigation into the networks responsible for the May offices on the Via Condotti in Rome. Under the current 12, 1982 attempt to assassinate Pope John Paul II has Grand Master, Prince Angelo de Mojana di Colonna, now uncovered the fact that Secretary of State Alexander the SMOM is controlled by the leading families of the Haig is a witting participant in a secret-cult network that Italian "black nobility," including the House of Savoy, poses the principal assassination-threat potential against Pallavicinis, Orsinis, Borgheses, and Spadaforas. both President Ronald Reagan and the Pope. The SMOM represents the higher-level control over This network centers upon the transnational branch the Propaganda-2 Masonic Lodge of former Mussolini es of the Hospitaler Order (a.k.a. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

About Fanjeaux, France Perched on the Crest of a Hill in Southwestern

About Fanjeaux, France Perched on the crest of a hill in Southwestern France, Fanjeaux is a peaceful agricultural community that traces its origins back to the Romans. According to local legend, a Roman temple to Jupiter was located where the parish church now stands. Thus the name of the town proudly reflects its Roman heritage– Fanum (temple) Jovis (Jupiter). It is hard to imagine that this sleepy little town with only 900 inhabitants was a busy commercial and social center of 3,000 people during the time of Saint Dominic. When he arrived on foot with the Bishop of Osma in 1206, Fanjeaux’s narrow streets must have been filled with peddlers, pilgrims, farmers and even soldiers. The women would gather to wash their clothes on the stones at the edge of a spring where a washing place still stands today. The church we see today had not yet been built. According to the inscription on a stone on the south facing outer wall, the church was constructed between 1278 and 1281, after Saint Dominic’s death. You should take a walk to see the church after dark when its octagonal bell tower and stone spire, crowned with an orb, are illuminated by warm orange lights. This thick-walled, rectangular stone church is an example of the local Romanesque style and has an early Gothic front portal or door (the rounded Romanesque arch is slightly pointed at the top). The interior of the church was modernized in the 18th century and is Baroque in style, but the church still houses unusual reliquaries and statues from the 13th through 16th centuries. -

The Development of Irrigation in Provence, 1700-1860: the French

Economic History Association The Development of Irrigation in Provence, 1700-1860: The French Revolution and Economic Growth Author(s): Jean-Laurent Rosenthal Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Sep., 1990), pp. 615-638 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2122820 . Accessed: 01/03/2012 07:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and Economic History Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History. http://www.jstor.org The Development of Irrigation in Provence, 1 700-1860: The French Revolution and Economic Growth JEAN-LAURENT ROSENTHAL Quantitative and qualitative evidence suggest that the returns to irrigationin France were similar during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Old Regime failed to develop irrigationbecause of fragmentedpolitical authority over rights of eminent domain. Since many groups could hold projectsup, transaction costs increased dramatically.Reforms enacted during the French Revolution reduced the costs of securingrights of eminent domain. Historians and economic historians hotly debate the issue of the French Revolution's contributionto economic growth. -

Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants from Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1934 Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish. Anna Theresa Daigle Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Daigle, Anna Theresa, "Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish." (1934). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8182. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOLKLORE AND ETYMOLOGICAL GLOSSARY OF THE VARIANTS FROM STANDARD FRENCH XK JEFFERSON DAVIS PARISH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SHE LOUISIANA STATS UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND MECHANICAL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES BY ANNA THERESA DAIGLE LAFAYETTE LOUISIANA AUGUST, 1984 UMI Number: EP69917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI EP69917 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). -

A Study of Louisiana French in Lafayette Parish. Lorene Marie Bernard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1933 A Study of Louisiana French in Lafayette Parish. Lorene Marie Bernard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Lorene Marie, "A Study of Louisiana French in Lafayette Parish." (1933). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8175. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the masterTs and doctorfs degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection* Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted* but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 1 1 9 -a A STUDY OF .LOUISIANA FRENCH IN LAF/lYETTE PARISH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE LOUISIANA STa TE UNITORS TY AND AGRICULTURAL AND MEDICAL COLLET IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OB1 THE REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH BY LOREBE MARIE BERNARD LAFAYETTE, LOUISIANA JUNE 19S3. -

Nobility in Middle English Romance

Nobility in Middle English Romance Marianne A. Fisher A dissertation submitted for the degree of PhD Cardiff University 2013 Summary of Thesis: Postgraduate Research Degrees Student ID Number: 0542351 Title: Miss Surname: Fisher First Names: Marianne Alice School: ENCAP Title of Degree: PhD (English Literature) Full Title of Thesis Nobility in Middle English Romance Student ID Number: 0542351 Summary of Thesis Medieval nobility was a compound and fluid concept, the complexity of which is clearly reflected in the Middle English romances. This dissertation examines fourteen short verse romances, grouped by story-type into three categories. They are: type 1: romances of lost heirs (Degaré, Chevelere Assigne, Sir Perceval of Galles, Lybeaus Desconus, and Octavian); type 2: romances about winning a bride (Floris and Blancheflour, The Erle of Tolous, Sir Eglamour of Artois, Sir Degrevant, and the Amis– Belisaunt plot from Amis and Amiloun); type 3: romances of impoverished knights (Amiloun’s story from Amis and Amiloun, Sir Isumbras, Sir Amadace, Sir Cleges, and Sir Launfal). The analysis is based on contextualized close reading, drawing on the theories of Pierre Bourdieu. The results show that Middle English romance has no standard criteria for defining nobility, but draws on the full range on contemporary opinion; understandings of nobility conflict both between and within texts. Ideological consistency is seldom a priority, and the genre apparently serves neither a single socio-political agenda, nor a single socio-political group. The dominant conception of nobility in each romance is determined by the story-type. Romance type 1 presents nobility as inherent in the blood, type 2 emphasizes prowess and force of will, and type 3 concentrates on virtue.