Beauty, Το Καλον, and Its Relation to the Good in the Works of Plato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing Oursel Es in the Xenoi – Plato's Warning to the Greeks

Akropolis 3 (2019) 129-149 Marina Marren* Seeing Ourseles in the Xenoi – Plato’s Warning to the Greeks Abstract: In this essay about the story of Atlantis in Plato’s Timaeus, we focus on the crucial political message that the Atlantis tale contains. More precisely, we seek to respond to a question that may evade a completely satisfactory answer. The question is: Could Plato’s story of the rise and fall of Atlantis, in the Timaeus, be a warning tale to the Greeks of his own time? In order to root the inves- tigation prompted by this question in solid textual ground, we pay close attention to the framing of the Atlantis tale. In what follows, we analyze the series of substitutions (between mythical, ancient, and historical cities, i.e., Atlantis, Athens, and Sais) that Plato uses as he seeks to bring his readers to a point from which we can assess the politics of ancient Athens – a city that in Plato’s time stands on the brink of repeating the political blunders of the formerly glorious empire of the East. Introduction In the spirit of the tradition that takes Plato’s dialogues to be both works of literary genius and of philosophy, we pay careful attention to Plato’s narrative frames and to his choice of interlocutors in order to tease out the philosoph- ical and political recommendations that Plato has for his ancient readers and that his dialogues offer to us. To that end, in Section II, we focus on providing philosophically pertinent details related to the identity and ambitions of Critias IV who, on our interpretation, is the narrator of the Atlantis story. -

Rethinking Athenian Democracy.Pdf

Rethinking Athenian Democracy A dissertation presented by Daniela Louise Cammack to The Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2013 © 2013 Daniela Cammack All rights reserved. Professor Richard Tuck Daniela Cammack Abstract Conventional accounts of classical Athenian democracy represent the assembly as the primary democratic institution in the Athenian political system. This looks reasonable in the light of modern democracy, which has typically developed through the democratization of legislative assemblies. Yet it conflicts with the evidence at our disposal. Our ancient sources suggest that the most significant and distinctively democratic institution in Athens was the courts, where decisions were made by large panels of randomly selected ordinary citizens with no possibility of appeal. This dissertation reinterprets Athenian democracy as “dikastic democracy” (from the Greek dikastēs, “judge”), defined as a mode of government in which ordinary citizens rule principally through their control of the administration of justice. It begins by casting doubt on two major planks in the modern interpretation of Athenian democracy: first, that it rested on a conception of the “wisdom of the multitude” akin to that advanced by epistemic democrats today, and second that it was “deliberative,” meaning that mass discussion of political matters played a defining role. The first plank rests largely on an argument made by Aristotle in support of mass political participation, which I show has been comprehensively misunderstood. The second rests on the interpretation of the verb “bouleuomai” as indicating speech, but I suggest that it meant internal reflection in both the courts and the assembly. -

Buch: Platonische Mythen

Platonische Mythen Was sie sind und was sie nicht sind Von A wie Atlantis bis Z wie Zamolxis Thorwald C. Franke Verlag Books on Demand Norderstedt 2021 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Vom selben Autor: Mit Herodot auf den Spuren von Atlantis. Aristoteles und Atlantis. Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis. Als Herausgeber: Gunnar Rudberg: Atlantis and Syracuse. Addenda & Corrigenda werden auf der Internetseite www.atlantis-scout.de gesammelt. Erste Auflage. © 2021 by Thorwald C. Franke. Alle Rechte liegen beim Autor. Dieses Werk ist einschließlich aller seiner Teile urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Autors unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigung, Übersetzung, Mikroverfilmung, Ver- filmung und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Konzeption, Text, Layout und Umschlaggestaltung: Thorwald C. Franke. Herstellung und Verlag: Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt. Printed in Germany. ISBN 978-3-7534-9212-4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort............................................................................................................15 Einführung.......................................................................................................19 Ein neuer Ansatz -

November 21,1895

ME 07. 0U BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 1895. NUMBER 47. Fish and Game. Capt. Benjamin At- Obituary. North port Mews. COUNTY CORRESPONDENCE. East Searsmont. Mrs. Journal. wood of Emily Arnold Personal. iifpuMuau Winterport, State game warden, has returned was in from a two weeks’ visit in Bangor Friday, on his return from Mr. Leonard Brooks Cobbett died in Bel- M. I. Stevens is teaching school at Beech- Belmont. Mr. Willis Sanborn of Morrill Franklin, S. H. Mathews went to Boston on EH V THURSDAY MORNING BY THE a the hill. Mass.Charles Mahoney of Monday trip along Canadian Pacific railway. fast Sunday, Nov. 17th, at the advanced age visited friends in town Sunday_The is business. Capt. Atwood that the recent snows Northport visiting his brother Arad_ says of 95 years and 16 He was born in Mess Bessie Patterson is friends North Belmont Association will have days. visiting Cemetery Oscar Hills and helped the hunters considerably. in wife of East Northport H. C. Pitcher was in Portland last week Lowell, Mass., but came to Belfast when Camden. have a sociable at Mystic Hall Tues- Last week he one Grange were in town Joiimal Co. arrested of the promi- last week, the guests of her on business. FibMlui about 10 years of age, which has been his Now don’t forget that the heavy rain of day evening, Nov. 26th, for the purpose of Ullicai nent citizens of Jackman for illegal fish- brother, Edgar P. Wm. Friday, Nov. 15, was accompanied by Mahoney_Mrs. S. Samuel Morse went to ing. The man a fine of £100. -

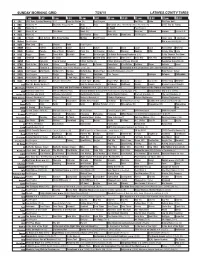

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Mcgilchrist and the Axial Age

Article In Search of the Origins of the Western Mind: McGilchrist and the Axial Age Susanna Rizzo 1 and Greg Melleuish 2,* 1 School of Arts & Sciences, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Cnr Broadway and Abercrombie St, P.O. Box 944, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] 2 School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2525, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 November 2020; Accepted: 12 January 2021; Published: 25 January 2021 Abstract: This paper considers and analyses the idea propounded by Iain McGilchrist that the foundation of Western rationalism is the dominance of the left side of the brain and that this occurred first in ancient Greece. It argues that the transformation that occurred in Greece, as part of a more widespread transformation that is sometimes termed the Axial Age, was, at least in part, connected to the emergence of literacy which transformed the workings of the human brain. This transformation was not uniform and took different forms in different civilisations, including China and India. The emergence of what Donald terms a “theoretic” culture or what can also be called “rationalism” is best understood in terms of transformations in language, including the transition from poetry to prose and the separation of word and thing. Hence, the development of theoretic culture in Greece is best understood in terms of the particularity of Greek cultural development. This transition both created aporias, as exemplified by the opposition between the ontologies of “being” and “becoming”, and led to the eventual victory of theoretic culture that established the hegemony of the left side of the brain. -

An Investigation Into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 10 Issue 10 Spring 2016 Article 5 Spring 2016 Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor University of Arkansas at Little Rock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Taylor, Reed. 2018. "Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 10 (Spring): 48-60. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol10/ iss10/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taylor: Bodies and Contexts Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor, University of Arkansas at Little Rock Abstract: In this article, I contribute to the wider discourse of theorizing feminism in predominantly Muslim societies by analyzing the role of women’s political agency within the writings of the twelfth-century Islamic philosopher Averroës (Ibn Rushd, 1126–1198). I critically analyze Catarina Belo’s (2009) liberal feminist approach to political agency in Averroës by adopting a postmodern reading of Averroës’s commentary on Plato’s Republic. A postmodern feminist reading of Averroes’s political thought emphasizes contingencies and contextualization rather than employing a literal reading of the historical works. -

Representation of American Dreams in the Good Lie (2014) Film

REPRESENTATION OF AMERICAN DREAMS IN THE GOOD LIE (2014) FILM A Thesis Submitted to Faculty of Adab and Humanities In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for The Degree of Strata One (S1) LUTHFI FADLAN 1112026000106 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE FACULTY OF ADAB AND HUMANITIES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2017 ABSTRACT Luthfi Fadlan, Representation of America Dreams in The Good Lie Film. A Thesis: English Language and Literature, Faculty of Adab and Humanities, State Islamic University of Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, 2017 The Good Lie is a 2014 American drama film written by Margaret Nagle, and directed by Philippe Falardeau. This thesis aims to observe the manifest of American Dreams value through representation of each Sudanese and American character construction. Using the Descriptive analysis and qualitative method to reveal the findings thus, this research describes the character construction of each Sudanese and American Characters through Stuart Hall Representation concept with constructionist approach and using the result as reflection of American Dreams from James Truslow Adams. All the data collected from the dialogues and the pictures of the film. The findings of this research explains the construction of Sudanese immigrant and American characters is in line with the value of American Dreams concept. It is seen with the achievement of Sudanese and American characters by looking; the success of Sudanese characters in achieving freedom, the success of Sudanese characters in realizing their own dreams, as well as the success of Sudanese and American characters in solving their own problems. The writer also find that the depiction of Sudanese and American character with their attainment in America can be seen as a film that reflects America as a capable place of giving freedom, equality of opportunity, to every Sudanese immigrant, and portrays America as a place that can accommodate individual or collective motive. -

SUDANESE REFUGEES' IDENTITY in the GOOD LIE FILM a Thesis

SUDANESE REFUGEES’ IDENTITY IN THE GOOD LIE FILM A Thesis Submitted to the Letters and Humanities Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Strata One (S1) By: MUHAMAD ADHI KURNIA 1111026000057 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT LETTERS AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2015 ABSTRACT Muhamad Adhi Kurnia, NIM: 1111026000057, Sudanese Refugees‟ Identity in The Good Lie Film. Thesis: English Letters Department, Letters and Humanities Faculty of Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta 2015. The Good Lie is a 2014 American drama film written by Margaret Nagle, and directed by Philippe Falardeau. The aim of this research is to see the identity construction of Sudanese refugees in The Good Lie film. Using the Descriptive analysis and qualitative method to reveal the findings, thus, this research describes the identity dynamics of three main characters and their identity constructions through Stuart Hall‘s basic identity concept and three very different conceptions, and supported by Kathryn Woodward‘s identity concept. All the data collected from the script dialogues and the cropped pictures of the film. The findings of this research explains the identity of someone or a group, in this case the Sudanese refugees affected by two things; life in the past and the future life (the recent life). After the identity construction, this research states that the Sudanese refugees‘ identities divided into the sociological subject. This happens due to the life of the Sudanese refugees experiencing the collision of culture and the identity negotiation, those interaction formed and modified the Sudanese refugees‘ identity but the subject still has an inner core or essence that is ―the real me‖ based on Hall‘s identity concept. -

INFLUENTIAL TIME for MONTRÉAL in BARCELONA for More Than a Century, the Mercè De Barcelone Has Been One of Europe’S Greatest Events

“At the top of all the charts, Montréal has acquired an enviable reputation on the world stage—and culture plays an important role in this.” Mélanie Joly Minister of Canadian Heritage Martin Coiteux Minister of Municipal Affairs and Land Occupancy, Minister of Public Security, Minister responsible for Montréal region INFLUENTIAL TIME FOR MONTRÉAL IN BARCELONA For more than a century, the Mercè de Barcelone has been one of Europe’s greatest events. This late-summer festival attracts more than two million participants and tourists. Montréal was the guest of honour in 2013. The program developed by Montréal featured the city’s digital creativity and artistic invent- iveness. Without a doubt, the highlight was provided by Moment Factory, based on an idea of Renaud – Architecture d’événe- ments: a multimedia spectacle projected on the facade of the Sagrada Família, Gaudí’s celebrated, if still unfinished, basilica. Titled Ode à la vie, it was a homage to the work of the Barcelona architect who, through the play of light and optics, emphasized lines and sculptures, while bringing poetic images to life, as if rising up from a dream. For three even- ings the show was acclaimed by thousands of enchanted spectators. A creation by Cirque Éloize, an electronic music performance presented by Piknic Électronik, a concert performed by traditional music group Le Vent du Nord and a festival of Québec films filled out this rich and varied programming—all in the image of the city they represent! Photo: Moment Factory @ Pep Daude Photo: © Ulysse Lemerise / OSA Images SWINGS IN THE SPRINGTIME Better than the swallows, 21 Balançoires are a and Radwan Ghazi Moumneh (for music swings sets off sounds and lights. -

The Good Lie Refugee Week Movie Night Evaluation

Greater Shepparton Women’s Charter Alliance Advisory Committee Refugee Week event: The Good Lie Movie Night Wednesday 17 June 2015 – Shepparton Evaluation M15/38121 Page | 1 Contents Greater Shepparton Women’s Charter Alliance Advisory Committee ........................................................................... 3 Refugee Week event – The Good Lie movie night .......................................................................................................... 3 Date ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Venue .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Movie – The Good Lie ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Speaker: ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sponsors/Partners ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 Audience.......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Autochthonie, Zugehörigkeit und Exklusion: Die widersprüchlichen Verflechtungen des Lokalen und Globalen in Afrika und Europa Geschiere, P.L. DOI 10.7788/ha.2013.21.1.85 Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Published in Historische Antropologie. Kultur, Gesellschaft, Altag Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Geschiere, P. L. (2013). Autochthonie, Zugehörigkeit und Exklusion: Die widersprüchlichen Verflechtungen des Lokalen und Globalen in Afrika und Europa. Historische Antropologie. Kultur, Gesellschaft, Altag, 21(1), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.7788/ha.2013.21.1.85 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 Autochthonie, Zugehörigkeit und Exklusion Die widersprüchlichen Verflechtungen des Lokalen und Globalen in Afrika und Europa1 von Peter Geschiere Einer der Widersprüche unserer Zeit ist die zunehmende Sorge um lokale Zugehö- rigkeit2 in einer Welt, die vorgibt, globalisiert zu sein.