Corruption and Reform in Democratic South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Zuma: the Man of the Moment Or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu

Research & Assessment Branch African Series Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu Key Findings • Zuma is a pragmatist, forging alliances based on necessity rather than ideology. His enlarged but inclusive cabinet, rewards key allies with significant positions, giving minor roles to the leftist SACP and COSATU. • Long-term ANC allies now hold key Justice, Police and State Security ministerial positions, reducing the likelihood of legal charges against him resurfacing. • The blurring of party and state to the detriment of public institutions, which began under Mbeki, looks set to continue under Zuma. • Zuma realises that South Africa relies too heavily on foreign investment, but no real change in economic policy could well alienate much of his populist support base and be decisive in the longer term. 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu INTRODUCTION Jacob Zuma, the new President of the Republic of South Africa and the African National Congress (ANC), is a man who divides opinion. He has been described by different groups as the next Mandela and the next Mugabe. He is a former goatherd from what is now called KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) with no formal education and a long career in the ANC, which included a 10 year spell at Robben Island and 14 years of exile in Mozambique, Swaziland and Zambia. Like most ANC leaders, his record is not a clean one and his role in identifying and eliminating government spies within the ranks of the ANC is well documented. -

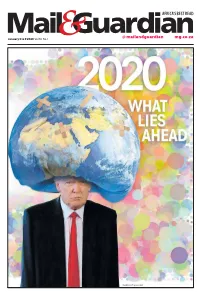

Africa's Best Read

AFRICA’S BEST READ January 3 to 9 2020 Vol 36 No 1 @ mailandguardian mg.co.za Illustration: Francois Smit 2 Mail & Guardian January 3 to 9 2020 Act or witness IN BRIEF – THE NEWS YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED Time called on Zulu king’s trust civilisation’s fall The end appears to be nigh for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls more than three million A decade ago, it seemed that the climate hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf crisis was something to be talked about of King Goodwill Zwelithini, after the govern- in the future tense: a problem for the next ment announced it will accept the recommen- generation. dations of the presidential high-level panel on The science was settled on what was land reform to review the trust’s operations or causing the world to heat — human emis- repeal the legislation. sions of greenhouse gases. That impact Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and had also been largely sketched out. More Rural Development Thoko Didiza announced heat, less predictable rain and a collapse the decision to accept the recommendations in the ecosystems that support life and and deal with barriers to land ownership human activities such as agriculture. on land controlled by amakhosi as part of a But politicians had failed to join the dots package of reforms concerned with rural land and take action. In 2009, international cli- tenure. mate negotiations in Copenhagen failed. She said rural land tenure was an “immedi- Other events regarded as more important ate” challenge which “must be addressed.” were happening. -

12-Politcsweb-Going-Off-The-Rails

http://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/going-off-the-rails--irr Going off the rails - IRR John Kane-Berman - IRR | 02 November 2016 John Kane-Berman on the slide towards the lawless South African state GOING OFF THE RAILS: THE SLIDE TOWARDS THE LAWLESS SOUTH AFRICAN STATE SETTING THE SCENE South Africa is widely recognised as a lawless country. It is also a country run by a government which has itself become increasingly lawless. This is so despite all the commitments to legality set out in the Constitution. Not only is the post–apartheid South Africa founded upon the principle of legality, but courts whose independence is guaranteed are vested with the power to ensure that these principles are upheld. Prosecuting authorities are enjoined to exercise their functions “without fear, favour, or prejudice”. The same duty is laid upon other institutions established by the Constitution, among them the public protector and the auditor general. Everyone is endowed with the right to “equal protection and benefit of the law”. We are all also entitled to “administrative action that is lawful, reasonable, and procedurally fair”. Unlike the old South Africa – no doubt because of it – the new Rechtsstaat was one where the rule of law would be supreme, power would be limited, and the courts would have the final say. This edifice, and these ideals, are under threat. Lawlessness on the part of the state and those who run it is on the increase. The culprits run from the president down to clerks of the court, from directors general to immigration officials, from municipal managers to prison warders, from police generals to police constables, from cabinet ministers to petty bureaucrats. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I Would

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record and extend my indebtedness, sincerest gratitude and thanks to the following people: * Mr G J Bradshaw and Ms A Nel Weldrick for their professional assistance, guidance and patience throughout the course of this study. * My colleagues, Ms M M Khumalo, Mr I M Biyela and Mr L P Mafokoane for their guidance and inspiration which made the completion of this study possible. " Dr A A M Rossouw for the advice he provided during our lengthy interview and to Ms L Snodgrass, the Conflict Management Programme Co-ordinator. " Mrs Sue Jefferys (UPE) for typing and editing this work. " Unibank, Edu-Loan (C J de Swardt) and Vodakom for their financial assistance throughout this work. " My friends and neighbours who were always available when I needed them, and who assisted me through some very frustrating times. " And last and by no means least my wife, Nelisiwe and my three children, Mpendulo, Gabisile and Ntuthuko for their unconditional love, support and encouragement throughout the course of this study. Even though they were not practically involved in what I was doing, their support was always strong and motivating. DEDICATION To my late father, Enock Vumbu and my brother Gcina Esau. We Must always look to the future. Tomorrow is the time that gives a man or a country just one more chance. Tomorrow is the most important think in life. It comes into us very clean (Author unknow) ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF ABBREVIATIONS/ ACRONYMS USED ANC = African National Congress AZAPO = Azanian African Peoples -

Objecting to Apartheid

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) OBJECTING TO APARTHEID: THE HISTORY OF THE END CONSCRIPTION CAMPAIGN By DAVID JONES Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the subject HISTORY At the UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR GARY MINKLEY JANUARY 2013 I, David Jones, student number 200603420, hereby declare that I am fully aware of the University of Fort Hare’s policy on plagiarism and I have taken every precaution to comply with the regulations. Signature…………………………………………………………… Abstract This dissertation explores the history of the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) and evaluates its contribution to the struggle against apartheid. The ECC mobilised white opposition to apartheid by focussing on the role of the military in perpetuating white rule. By identifying conscription as the price paid by white South Africans for their continued political dominance, the ECC discovered a point of resistance within apartheid discourse around which white opposition could converge. The ECC challenged the discursive constructs of apartheid on many levels, going beyond mere criticism to the active modeling of alternatives. It played an important role in countering the intense propaganda to which all white South Africans were subject to ensure their loyalty, and in revealing the true nature of the conflict in the country. It articulated the dis-ease experienced by many who were alienated by the dominant culture of conformity, sexism, racism and homophobia. By educating, challenging and empowering white citizens to question the role of the military and, increasingly, to resist conscription it weakened the apartheid state thus adding an important component to the many pressures brought to bear on it which, in their combination, resulted in its demise. -

Abstract This Paper Explores the Under-Appreciated Role of Business

Business and the South African Transition Itumeleng Makgetla and Ian Shapiro Draft: February 20, 2016 Abstract This paper explores the under-appreciated role of business in negotiated transitions to democracy. Drawing on our interviews of key South African business leaders and political elites, we show how business played a vital role in enabling politicians to break out of the prisoners’ dilemma in which they had been trapped since the 1960s and move the country toward the democratic transition that took place in 1994. Business leaders were uniquely positioned to play this role, but it was not easy because they were internally divided and deeply implicated in Apartheid’s injustices. We explain how they overcame these challenges, how they facilitated negotiations, and how they helped keep them back on track when the going got rough. We also look at business in other transitional settings, drawing on South Africa’s experience to illuminate why business efforts to play a comparable role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have failed. We end by drawing out the implications of our findings for debates about democratic transitions and the role of business interests in them. Department of Political Science, P.O. Box 208301, New Haven, CT 06520-830. Phone:(203) 432-3415; Fax: (203): 432- 93-83. Email: [email protected] or [email protected] On March 21, 1960, police opened fire on a demonstration against South Africa’s pass laws in Sharpeville, fifty miles south of Johannesburg, killing 69 people. The callousness of the massacre – many victims were shot in the back while fleeing – triggered a major escalation in the conflict between the African National Congress (ANC) and the National Party (NP) government. -

Caleemo Saarka Madaxweyne Jacob Zuma —— Eeg Bogga 2

MAY 17 2009 Cadadka 12aad Madaxa Wargayska : Tifaftiraha Wargayska: Maxamed Raage Xog-Maal waa Wargays ku hadla Afkaaga Maxamed Muuse Nuur Hooyo soona baxa Bishii labo jeer. h. Maxamed Idiris ayaa socdaal dacwo faafin S ah ku maraya dalka K/Afrika , socdaalkiisa oo kasoo billoowdey magaalada Johannesburg ayuu ku maray magaalooyin dhowr ah oo ay Soomaalidu degentahay, Xog-Maal waxay idiin soo gubineysaa warbixin ku saabsan socdaalka Sheekha — Eeg Boga 3aad Caleemo Saarka Madaxweyne Jacob Zuma —— Eeg Bogga 2 Bogga 13aad Qodobada Wargeyska Qodobada —Qaxooti guryo -XUURAAN: laga burburiyey-- ku garab qabo Eag Bogga 7aad... ku qadi meey- —Shaqada Shanta side-- Eeg Beri Eeg Bogga Bogga 10 aad 4aad.. -- Sh. Shariif “Alla KFC Saliid — Sanad Guuradii maxaa heley? Baddanaa”bogga Xenophobia Eeg Iyo Eeg Boga 9aad Eeg Boga 8aad.. Bogga 4aad…. 7aad... Soo saaristaan waxaa ku jira aayadaha Qur’aanka Kariimka iyo Axaadiista Nabigeena (SCW) Ee Fadlan hadhigin meel aan munaasan u ahayn Wargayska. Fadlan kusoo dir wixii talooyin iyo tusaale ah ooaad wargayska u hayso E-mail [email protected] ama 26 Durban road pelville Cape Town 17 May, 2009 XOG-MAAL 2 Waa kuwan magacyadii 17. Wasaarada Tamarta: Dipuo Peters 35. Ku xigeenka wasaarada : Fikile Mbalula oo dhamaystiran. 18. Wasaarada maaliyada : Pravin Gord- 36. Wasaarada macaahiida dowliga ah : Bar- han bara Hogan 1. Wasaarada beeraha, dhirta iyo daaqa iyo kalluumeysiga : Tina Joemat- 19. Ku xigeenka wasaarada: Nhlanhla 37. Ku xigeenka wasaarada : Enoch Godong- wana Pettersson Nene 2. Wasiir ku xigeenka: Dr Pieter Mulder 38. Wasaarada shaqaalaha dowlada iyo maa- 20. Wasaarada caafimaadka : Aaron mulka : Richard Baloyi Motsoaledi 3. -

The ANC Political Underground in the 1970S

The ANC Political Underground in the 1970s By Gregory Houston and Bernard8 Magubane We knew that the ANC was operating because we could hear that this person was being charged in Durban, in Cape Town, in Grahamstown, and so on. We would always hear from the papers of ANC activity. We heard about the operations in which ANC guerrillas were involved with the fascist police and soldiers in Zimbabwe, as they were trying to go back home to begin the war of liberation in South Africa. From time to time there were ANC pamphlets and journals which we used to get and we saw very little of any underground activity except by the ANC.1 This chapter is divided into two sections. In the first section the focus is on the underground political work of individuals and small groups of people based inside South Africa. We begin by looking at the activities in the early 1970s of internal underground activists in ANC networks that were initiated during the second half of the 1960s, with a focus on the Johannesburg area. This is followed by case studies of individuals who became involved in underground activities by linking up with ANC activists based inside the country or those in exile. We also focus on the activities of a few individuals who decided to take the initiative to become involved in underground political work without linking up with any of the liberation movements. These case studies are based on the life histories of a few selected people in an attempt to demonstrate some of the distinguishing characteristics of participation in internal underground activities. -

Two Cheers? South African Democracy's First Decade

Review of African Political Economy No.100:193-202 © ROAPE Publications Ltd., 2004 Two Cheers? South African Democracy’s First Decade Morris Szeftel The contributions in this issue mark the tenth anniversary of democracy and political liberation in South Africa. They are a selection of the papers originally presented to a Workshop organised in September 2003 in Johannesburg by the Democracy and Governance section of the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa. We are grateful to Roger Southall, its director, and to John Daniel for organising the conference, agreeing to a joint publication of papers with ROAPE and co-editing this issue. All the contributors are scholars and activists living and working in South Africa. It is fitting that an assessment of the first decade of democracy in South Africa should also be the 100th issue of The Review of African Political Economy. From its beginnings in 1974, ROAPE’s commitment to the liberation and development of Africa always had the struggle for a democratic South Africa as one of its central themes. Alongside many others, contributors to the journal consistently viewed the fight against racial capitalism in South Africa as critical for the future of Africa as a whole; indeed, as one which defined ideas of justice and decency for all humanity. Writing on the 75th anniversary of the founding of the ANC, the editors argued that ‘its principles, expressed through the Freedom Charter, have come to stand for a democratic alternative in South Africa. It is the white state which today represents barbarism; the principles of the Charter which represent decency and civilisation’ (Cobbett et al, 1987:3). -

Political Elites and Anticorruption Campaigns As “Deep” Politics of Democracy a Comparative Study of Nigeria and South Africa

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 15, No. 1: 159-181 Political Elites and Anticorruption Campaigns as “Deep” Politics of Democracy A Comparative Study of Nigeria and South Africa Olugbemiga Samuel Afolabi Abstract Studies of elite corruption and anticorruption have provided insight into their embeddedness in political and democratic processes. Since the return to democracy in 1999 in Nigeria, and independence in 1994 in South Africa, there has been growing interest in the relationship among corruption, anticorruption, and democracy. Despite these early advances of the study of elite corruption, the many ways that elite corruption and efforts against it have become part of the “hidden transcripts” of power and democracy in Africa remain unexamined. Using secondary data, this research examines corruption and the need for its reduction as a crucial ingredient in the politics of democracy in contemporary Africa. From a comparative perspective, the study focuses on the relationship between democracy and its antithesis, corruption, as one of mutual entanglement and co-constitutive aspects of politics in two African states: Nigeria in Anglophone West Africa and South Africa in Southern Africa. The entangled, yet antithetical relationship between corruption and democracy in these two countries means that for the political elite in Nigeria and South Africa, the quest for democracy calls for an embattlement against corruption through sustained rhetoric and practice of anticorruption politics. The essay explains how the interplay between corruption -

Global and Local Narratives of the South African General Elections

DESPERATELY SEEKING DEPTH: Global and local narratives of the South African general elections on television news, 1994 – 2014 By Bernadine Jones Town Cape Thesis presentedof for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the Centre for Film and Media Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN UniversityAugust 2017 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration of own work and publications This thesis is my own work, conducted in Cape Town, South Africa between January 2014 and August 2017. I confirm that I have been granted permission by the University of Cape Town’s Doctoral Degrees Board to include the following publication(s) in my PhD thesis: Jones, B. 2016. Television news and the digital environment: a triadic multimodal approach for analysing moving image media, in African Journalism Studies 37(2): 116-137 2 Acknowledgements What respectable body of work would be complete without expressing ones gratitude to those who have helped carry the author – mind, soul, and sometimes body – through the wilderness of research and analysis? It stands to reason then that I convey my utmost appreciation for my two supervisors, Drs Martha Evans and Wallace Chuma, for guiding me along this path with infinite patience, wisdom, and maddening attention to detail without which I would flounder. -

Against Apartheid

REPORT OF THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE AGAINST APARTHEID GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: FORTY-FOURTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 22 (A/44/2~) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1990 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed ofcapital letters combined with figures. Mention of sl!ch a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The present. report was also submitted to the Security Council under the symbol S/20901. ISSN 0255-1845 1111 iqlllllll l~uqllHh) I!i li'alHlltHy 19~O 1 CONTENTS LBTTER OF TRANSMITTAL •••••••••••••••••••••••••••• l1li •• l1li ••••••••••••••••••••••• PART ONE ~~AL RBPORT OF THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE •...•....••............... 1 275 2 I • INTRODUCTION ••••••••••.•••.••.••.......•.......•. l1li •••••••• 1 1 3 11. RBVIBW OF DEVELOPMENTS IN SOUTH AFRICA .........•.......... [, q4 1 A. General political conditions !l 15 4 B. Repression of the r~pulation .......................... 1.6 4" () 1.. Overview ...•.......•.............................. 1(; fi 2. Political trials, death sentences and executions .. I.., - 7.4 r; 3. Detention without trial ?!l 7.11 IJ 4. Vigilante groups, death squads and covert activities .. ' . 29 35 y 5. Security laws, banning and restriction or(\ers ..... lfi :19 11 6. Forced population removals ..••....••...•.......... 10 .. 45 12 7. Press censorship I ••••••••• 46 - 47 13 C. Resistance to apartheid .•.......•..................... 411 .. 03 13 1. Organizing broader fronts of resistance .....•..... 40 5n 11 2. National liberation movements . !i9 1;1 I. t) 3. Non-racial trade union movement Ij tl 1;9 l" 4. Actions by religious, youth and student gr Il\lllt~ ••.. "10 .,., III 5. Whites in the resistance . "111 1I:cl ),0 1)4 D. Destabilization and State terrorism . " 'I 7.2 Ill. EXTERNAL RELATIONS OF SOUTH AFRICA , .