THE GERSHWINS' TIP-TOES Music and Lyrics by GEORGE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Gershwin Edited by Anna Harwell Celenza Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42353-3 — The Cambridge Companion to Gershwin Edited by Anna Harwell Celenza Index More Information Index Aarons, Alex, 7 Barkleys of Broadway (1949) film, 206, 214 Ager, Cecelia, 294 Bartók, Bela, 119 Ager, Milton, 294 “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” 36 Albee, Edward, 67 Bauer, Marion, 222 Alberts, Charles S., 138 “Beale Street Blues,” 238 Alda, Robert, 134 Beethoven, Ludwig van, 9, 35, 76, 225 Alexander III, Czar of Russia, 5 Rondo a Cappricio, Op. 129, 37 Allen, Gracie, 207, 212, 213 Sonata in F Minor, Op. 57 (“Appassionata”), Americana (1928) musical, 10 37 An American in Paris (1951) film, 214, 240, 262 Sonata Op. 110, 37 An American in Paris (2015) musical, 262, 264, Sonata Op. 81, 37 265, 266, 267, 269, 270 String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 4, 37 Anchors Aweigh (1945) film, 254 “ ” Anderson, Marian, 191 Symphony No. 3 ( Eroica ), 37 Antheil, George, 155–56, 229 Symphony No. 5, 248 Ballet mécanique, 155, 156 Symphony No. 7, 37 Jazz Symphony, 156 Bennett, Robert Russell, 47, 199, 201, 211, 212, Anything Goes (1936) film, 200 214, 216 Arcadelt, Jacques, 36 Bennett, Tony, 238 Arden, Victor, 93, 97, 268 Benton, Thomas Hart, 162 Arlen, Harold, 9, 47, 49, 199, 276, 277 Berg, Alban, 162, 225, 229 “Stormy Weather,” 277 Lyric Suite, 33, 162 Arlen, Michael, 154 Wozzeck, 231 Armitage, Merle, 48, 53, 291 Bergere, Valerie, 72 Armstrong, Louis, 244, 277 Berkeley, Busby, 45 Arvey, Verna, 25 Berlin, 161 Asian American Jazz Orchestra, 256 Berlin, Irving, 44, 48, 53, 61, 64, 68, 69, 93, 154, Askins, Harry, 132 225, 239, 244, -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Anything Goes - the Maiden Voyage

ANYTHING GOES - THE MAIDEN VOYAGE Damaged both by Depression and the new "talkies", no fewer than 83% of Broadway shows were financial failures in the 1931-32 season. But then, with the New Deal and the National Recovery Act promising employment and future prosperity and the end of crime-infested Prohibition, on 5th December 1933 New York came back to life. The blossoming of Broadway came a little later, but it did come. Anything Goes (1934) personifies perhaps more than any other show, the new optimism of post-Depression America. Anything Goes was produced by Vinton Freedley. Having dissolved a debt-ridden partnership with Alex Aarons, (another Broadway producer), Freedley had narrowly escaped his creditors. Lazing on a fishing boat, he began to conceive his next project about a group of eccentric characters aboard a cruise ship bound for England. He envisaged a small-scale show with book and lyrics by Jerome Kern, Guy Bolton and PG Wodehouse. Kern was destined not to work on the show and his place was taken by Cole Porter: Bolton and Wodehouse, despite living in Europe would eventually complete the trio. The custom was to build an original show around popular stars of the day. Freedley chose the comedy team of William Gaxton and Victor Moore and the young Ethel Merman, all of whom were currently enjoying considerable success in Gershwin musicals. He journeyed to Europe to meet his writers and hired Howard Lindsay in the USA to direct the show and make any editorial changes that may prove necessary. By mid- August, Freedley received the Bolton-Wodehouse manuscript and Porter score; the stars were signed in mid- September and a tryout was planned before bringing the show to New York in late October. -

Program Notes

“Come on along, you can’t go wrong Kicking the clouds away!” Broadway was booming in the 1920s with the energy of youth and new ideas roaring across the nation. In New York City, immigrants such as George Gershwin were infusing American music with their own indigenous traditions. The melting pot was cooking up a completely new sound and jazz was a key ingredient. At the time, radio and the phonograph weren’t widely available; sheet music and live performances remained the popular ways to enjoy the latest hits. In fact, New York City’s Tin Pan Alley was overflowing with "song pluggers" like George Gershwin who demonstrated new tunes to promote the sale of sheet music. George and his brother Ira Gershwin composed music and lyrics for the 1927 Broadway musical Funny Face. It was the second musical they had written as a vehicle for Fred and Adele Astaire. As such, Funny Face enabled the tap-dancing duo to feature new and well-loved routines. During a number entitled “High Hat,” Fred sported evening clothes and a top hat while tapping in front of an enormous male chorus. The image of Fred during that song became iconic and versions of the routine appeared in later years. The unforgettable score featured such gems as “’S Wonderful,” “My One And Only,” “He Loves and She Loves,” and “The Babbitt and the Bromide.” The plot concerned a girl named Frankie (Adele Astaire), who persuaded her boyfriend Peter (Allen Kearns) to help retrieve her stolen diary from Jimmie Reeve (Fred Astaire). However, Peter pilfered a piece of jewelry and a wild chase ensued. -

Jazz Arts Program Student 2019-2020

JAZZ ARTS PROGRAM STUDENT 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome/Introduction 3 Applied Lessons 4 Your Teacher 4 Change of Teacher 4 Dividing Lessons Between Two Teachers 4 Professional Leave 5 Attendance Policy 5 Playing-related Pain 5 Ensemble and Audition Requirements 6 Juries 7 Jury for Non-graduating Students 7 Advanced Standing Jury 7 Jury Requirements for Performance Majors 8 Jury Requirements for Composition Majors 9 Comments 9 Grading 9 Postponement 9 Recitals 10 Scheduling Recitals 10 Non-required Recitals 10 Required Recitals - Undergraduate and Graduate 10 Recording of Recitals 11 Department Policies 12 Attendance 12 Subs 12 Attire 12 Grading System 13 Equipment 13 Jazz Arts Program Communications: E-mail, 13 Student Website Faculty/Student Conferences 14 Contacting the Jazz Arts Program Staff 14 Repertoire Lists 15 2 WELCOME/INTRODUCTION Dear Students, Welcome to the MSM family! We are a community of artists, educators and dreamers located in the thriving mecca and birthplace of modern jazz, Harlem, NY. This is the beginning of a journey that will undoubtedly have a major impact on the rest of your lives. As a former student, I spent the most important and transformative years of my artistic life at MSM. It was during my time here that I acquired the musical skills necessary to articulate my story in organized sound. The success of our MSM family is predicated upon three fundamental core values: Love ( empathy), Trust and Respect Jazz is an art form born from a desire to authentically express one’s individuality. Inherent in its construct is a deep understanding and appreciation for the value of an inclusive culture rich in diverse perspectives. -

OPERA, COMIC OPERA, MUSICAL Box 4/1

Enid Robertson Theatre Programme Collection MSS 792 T3743.R OPERA, COMIC OPERA, MUSICAL Box 4/1 Artist Date Venue, notes Melba, Dame Nellie, with Frederic Griffith 12.11.1902 Direction Mr George (Flute), Llewela Davies (Piano) M. (Second Musgrove Bensaude (Vocal) Signorina Sassoli Concert:15.11) Town Hall, Adelaide (Harp)Louis Arens, (Vocal)Dr. F. Matthew Ennis (Piano) Handel, Thomas, Arditi. Melba, Dame Nellie with, Tom Burke 15.6.1919 Royal Albert Hall, (Tenor), Bronislaw Huberman (Violin) London Frank St. Leger (Piano) Arthur Mason (Organ) Verdi, Puccini, etc. Melba, Dame Nellie 4.10.1921 Manager, John Lemmone, With Una Bourne (Piano), W.F.G.Steele (Second Concert Town Hall, Adelaide (Organ), John Lemmone (Flute) Mozart, 6.10.21) Verdi Melba, Dame Nellie & J.C. Williamson 26.9.1924 Direction, Nevin Tait Grand Opera Season , Aida (Verdi) Theatre Royal Adelaide Conductor Franco Paolantonio, with Augusta Concato, Phyllis Archibald, Nino Piccaluga, Edmondo Grandini, Gustave Huberdeau, Oreste Carozzi Melba, Dame Nellie & J.C. Williamson, 4.10.1924 Direction, Nevin Tait Grand Opera Season, Andrea Chenier, Theatre Royal Adelaide (Giordano) First Adelaide Performance, Franco Paolantonio (Conductor) Nino Piccaluga, Apollo Granforte, Doris McInnes, Antonio Laffi, Oreste Carozzi, Gaetano Azzolini, Luigi Cilla, Luigi Parodi, Antonio Venturi, Alfredo Muro, Vanni Cellini Melba, Dame Nellie & J.C. Williamson, 6.10.1924 Direction, Nevin Tait Grand Opera Season, DonPasquale, Theatre Royal, Adelaide (Donizetti) First Performance in Adelaide, Arnaldo -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

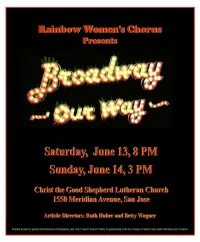

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more. -

Nikki Chooi with Stephen De Pledge Michael Hill International Violin Competition

Nikki Chooi with Stephen De Pledge Michael Hill International Violin Competition This recording is an element of the First Prize of the Michael Hill International Violin Competition, won by Nikki Chooi in June 2013. The Michael Hill International Violin Competition aims to recognise and encourage excellence and musical artistry, and to expand performance opportunities for young violinists from all over the world who are launching their professional careers and who aspire to establish themselves on the world stage. Since its inauguration in 2001, the ‘Michael Hill’ Winning performance with has achieved global standing as a competition, Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, and elevated to international recognition June 2013 a succession of young violinists. It delivers wraparound New Zealand hospitality and a genuine commitment to the development of every participating artist. George Gershwin Born Brooklyn, New York, 26 September 1898 Died Hollywood, California, 11 July 1937 Three Preludes Allegro ben ritmato e deciso Andante con moto e poco rubato Allegro ben ritmato e deciso George Gershwin was the second son of Russian immigrant parents and grew up in the densely populated area of the Lower East Side in New York, where he was in close contact with both European immigrants and African-Americans, and where young George’s well-developed street skills earned him a reputation of being rather wild. Around 1910 the Gershwin family acquired a piano, ostensibly for the eldest child, Ira, to learn. However, George was the first to use the instrument when it arrived and his parents were amazed to discover that he had learned to play on a friend’s ‘player piano’. -

Wodehouse and the Baroque*1

Connotations Vol. 20.2-3 (2010/2011) Worcestershirewards: Wodehouse and the Baroque*1 LAWRENCE DUGAN I should define as baroque that style which deli- berately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) all its pos- sibilities and which borders on its own parody. (Jorge Luis Borges, The Universal History of Infamy 11) Unfortunately, however, if there was one thing circumstances weren’t, it was different from what they were, and there was no suspicion of a song on the lips. The more I thought of what lay before me at these bally Towers, the bowed- downer did the heart become. (P. G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters 31) A good way to understand the achievement of P. G. Wodehouse is to look closely at the style in which he wrote his Jeeves and Wooster novels, which began in the 1920s, and to realise how different it is from that used in the dozens of other books he wrote, some of them as much admired as the famous master-and-servant stories. Indeed, those other novels and stories, including the Psmith books of the 1910s and the later Blandings Castle series, are useful in showing just how distinct a style it is. It is a unique, vernacular, contorted, slangy idiom which I have labeled baroque because it is in such sharp con- trast to the almost bland classical sentences of the other Wodehouse books. The Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary describes the ba- roque style as “marked generally by use of complex forms, bold or- *For debates inspired by this article, please check the Connotations website at <http://www.connotations.de/debdugan02023.htm>. -

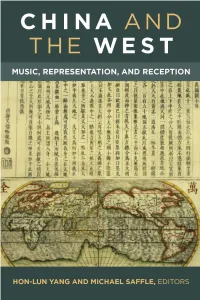

China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception

Revised Pages China and the West Revised Pages Wanguo Quantu [A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World] was made in the 1620s by Guilio Aleni, whose Chinese name 艾儒略 appears in the last column of the text (first on the left) above the Jesuit symbol IHS. Aleni’s map was based on Matteo Ricci’s earlier map of 1602. Revised Pages China and the West Music, Representation, and Reception Edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Yang, Hon- Lun, editor. | Saffle, Michael, 1946– editor. Title: China and the West : music, representation, and reception / edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016045491| ISBN 9780472130313 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472122714 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Music—Chinese influences. | Music—China— Western influences. | Exoticism in music. -

The Dale Warland Singers Presents GLORIOUS GERSHWIN MUSIC by GEORGE GERSHWIN LYRICS by IRA GERSHWIN

The Dale Warland Singers presents GLORIOUS GERSHWIN MUSIC BY GEORGE GERSHWIN LYRICS BY IRA GERSHWIN FRIDAY, MAY 13, 1988 ORCHESTRA HALL 8:00 P.M. THE DALE WARLAND SINGERS Dale Warland, Music Director Sigrid Johnson, Assistant Conductor "jerry Rubino, Pianist and Cabaret Singers Conductor GUEST ARTISTS MOORE BY FOUR Sanford Moore, director/piano Ginger Commodore, soprano Yolande Bruce-Crim, mezzo-soprano Connie Evingson, alto Dennis Spears, baritone Soli Hughes, guitar Jay Young, bass Robert Commodore, drums Paul Oakley, piano Don Stille, synthesizer Tom Hubbard, bass Gordy Knudtson; drums Randy Winkler, production SPECIAL MUSICAL ARRANGEMENTS Steve Barnett Jerry Rubino •This evening's concert is the result of the creative collaboration of many in- dividuals. Particular recognition is extended toJerry Rubino of the DWS ar- tistic staff for his leadership in providing the program conception and musical direction to this event as well as his outstanding musical arrangements. Glorious Gershwin is sponsored by IDS Financial Services Inc. and WAYL Radio . AM 980-FM94 (Special thanks to jefferson Transporunton Group for providing hus servic-e••for (he: pre-concert gala dinner; All musical arrangements are byJerry Rubino unless otherwise noted. I. Strike Up the Band I Got Rhythm Fascinating Rhythm (Mattson) Cabaret Singers By Strauss (Gershwin) Sigrid Johnson, soprano Strike Up the Band (King) II. He Loves and She Loves Nice Work If}fJu Can Get It Soon Ruth Spiegel, soprano; David Benson, bass Looking for a Boy Melissa O'Neill, soprano The Man I Love Lynette johnson, alto Oh, Lady Be Good Tim Sawyer, tenor; Gary Kortemeier, tenor; Michael Dailey, baritone; Brad Bak, bass Somebody Loves Me (Lyrics by B.G.