Studying the Lindbergh Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

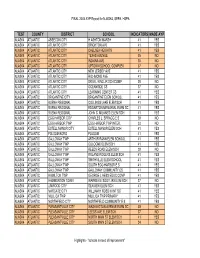

AYP 2003 Final Overall List

FINAL 2003 AYP Report for NJASK4, GEPA, HSPA TEST COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL INDICATORSMADE AYP NJASK4 ATLANTIC ABSECON CITY H ASHTON MARSH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY BRIGHTON AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY CHELSEA HEIGHTS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY TEXAS AVENUE 35 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY INDIANA AVE 35 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY UPTOWN SCHOOL COMPLEX 37 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY NEW JERSEY AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY RICHMOND AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY DR M L KING JR SCH COMP 38 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY OCEANSIDE CS 37 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY LEARNING CENTER CS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BRIGANTINE CITY BRIGANTINE ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL COLLINGS LAKE ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL EDGARTON MEMORIAL ELEM SC 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL JOHN C. MILANESI ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR CITY CHARLES L. SPRAGG E S 39 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR TWP EGG HARBOR TWP INTER. 33 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ESTELL MANOR CITY ESTELL MANOR ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC FOLSOM BORO FOLSOM 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP ARTHUR RANN ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP COLOGNE ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP REEDS ROAD ELEM SCH 39 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP ROLAND ROGERS ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP SMITHVILLE ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP SOUTH EGG HARBOR E S 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP. GALLOWAY COMMUNITY CS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC -

Niall Palmer

EnterText 1.1 NIALL PALMER “Muckfests and Revelries”: President Warren G. Harding in Fact and Fiction This article will assess the development of the posthumous reputation of President Warren Gamaliel Harding (1921-23) through an examination of key historical and literary texts in Harding historiography. The article will argue that the president’s image has been influenced by an unusual confluence of factors which have both warped history’s assessment of his administration and retarded efforts at revisionism. As a direct consequence, the stereotypical, deeply negative, portrait of Harding remains rooted in the nation’s consciousness and the “rehabilitation” afforded to many presidents by revisionist writers continues to be denied to the man still widely-regarded as the worst president of the twentieth century. “Historians,” Eugene Trani and David Wilson observed in 1977, “have not been gentle with Warren G. Harding.”1 In successive surveys of American political scientists, historians and journalists, undertaken to rank presidents by achievement, vision and leadership skills, the twenty-ninth president consistently comes last.2 The Chicago Sun- Times, publishing the findings of fifty-eight presidential historians and political scientists in November 1995, placed Warren Harding at the head of the list of “The Ten Worst” Niall Palmer: Muckfests and Revelries 155 EnterText 1.1 Presidents.3 A 1996 New York Times poll branded Harding an outright “failure,” alongside two presidents who presided over the pre-Civil War crisis, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. The academic merit and methodological underpinnings of such surveys are inevitably flawed. Nonetheless, in most cases, presidential status assessments are fluid, reflecting the fluctuations of contemporary opinion and occasional waves of academic revisionism. -

Today's Fbi. It's for You

PLEASE BE AWARE THAT THIS IS AN ADVERTISEMENT, NOT A JOB POSTING FOR THE SPECIAL AGENT POSITION. The FBI is collecting resumes of those interested in future employment as an FBI Agent. Individuals that meet the FBI’s Special Agent preliminary requirements will be notified by email once the actual application is available. TODAY'S FBI. IT'S FOR YOU. The strength of the FBI is its people – employees from different backgrounds, each possessing a myriad of skills, working together to ensure the safety of our communities and the nation. Each year, people from every industry, ethnicity, and environment apply to become members of the most prestigious law enforcement agency in the world. A unique, challenging and life-changing experience that will stretch you beyond your comprehension, the Special Agent position is more than a job – it is a calling to protect and defend your country, uphold and enforce the laws in your community and provide law enforcement assistance where and when, necessary. Bring your skills and dedication. We’ll make you an Agent. FBI Special Agents are responsible for enforcing over 300 federal statutes and conducting sensitive national security investigations. A career as a Special Agent offers unparalleled opportunities for new experiences and personal and professional growth. Listed below are some of our most sought after specialties: FBI SPECIAL AGENT: CERTIFIED PROFESSIONAL ACCOUNTANT (CPA) All crime leaves a money trail - at the FBI, we track it back to its source, investigate the participants and develop a case. As such, the FBI is seeking Certified Professional Accountants (CPAs) for the Special Agent position. -

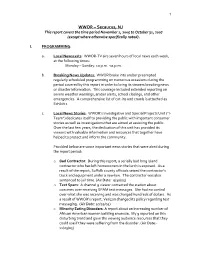

WWOR – Secaucus, NJ This Report Covers the Time Period November 1, 2005 to October 31, 2007 (Except Where Otherwise Specifically Noted)

1 WWOR – Secaucus, NJ This report covers the time period November 1, 2005 to October 31, 2007 (except where otherwise specifically noted). I. PROGRAMMING: a. Local Newscasts: WWOR‐TV airs seven hours of local news each week, at the following times: Monday – Sunday: 10 p.m. ‐11 p.m. b. Breaking News Updates: WWOR broke into and/or preempted regularly scheduled programming on numerous occasions during the period covered by this report in order to bring its viewers breaking news or disaster information. This coverage included extended reporting on severe weather warnings, amber alerts, school closings, and other emergencies. A comprehensive list of cut‐ins and crawls is attached as Exhibit 1 c. Local News Stories: WWOR’s Investigative and Special Projects Unit (“I‐ Team”) dedicates itself to providing the public with important consumer stories as well as investigations that are aimed at assisting the public. Over the last few years, the dedication of this unit has provided its viewers with valuable information and resources that together have helped to protect and inform the community. Provided below are some important news stories that were aired during the report period: o Bad Contractor: During this report, a serially bad long Island contractor who has left homeowners in the lurch is exposed. As a result of the report, Suffolk county officials seized the contractor’s truck and equipment under a new law. The contractor was also sentenced to jail time. (Air Date: 9/30/05) o Text Spam: A channel 9 viewer contacted the station about concerns over receiving SPAM text messages. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

Red Scare: FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 Schmidt, Regin

www.ssoar.info Red scare: FBI and the origins of anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 Schmidt, Regin Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Schmidt, R. (2004). Red scare: FBI and the origins of anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271396 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press RED SCARE Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. FBI and the origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943; e-book. 2004. ISBN 87 635 0012 4 Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. FBI and the origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943; e-book. 2004. ISBN 87 635 0012 4 Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press Regin Schmidt RED SCARE FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 e-Book Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. FBI and the origins of Anticommunism MUSEUM TUSCULANUM PRESS in the United States, 1919-1943; e-book. 2004. ISBN 87 635 0012 4 UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN 2000 [e-book – 2004] Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. -

The Last Days of Mussolini & Fascist Italy — Vikings in the Midwest

The one book every subscriber MUST have in the home library . BRINGING HISTORY INTO ACCORD WITH THE FACTS IN THE TRADITION OF DR. HARRY ELMER BARNES MARCH OF THE TITANS The Barnes Review A JOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE VOLUME XVIII NUMBER 3 MAY/JUNE 2012 BARNESREVIEW.COM ere it is: the complete and comprehensive history of the White race, spanning 500 centuries of tumultuous events from the Hsteppes of Russia to the African conti- nent, to Asia, the Americas and beyond. This is their inspirational story—of vast visions, empires, achieve- ments, triumphs against staggering odds, reckless blunders, crushing defeats and stupendous struggles. Most importantly of all, revealed in this work is the one true cause of the rise and fall of the world’s greatest empires—that all civilizations rise and fall according to their racial homogeneity and nothing else—a nation can survive wars, defeats, natural catastrophes, but not racial dissolution. This is a rev- olutionary new view of history and of the causes of the crisis facing modern Western Civilization, which will permanently change your understanding of history, race and society. Covering every continent, every White country both ancient and modern, and then stepping back to take a global view of modern racial realities, this book not Also inside this issue: only identifies the cause of the collapse of ancient civilizations, but also applies these lessons to modern Western society. The author, Arthur Kemp, spent more than 25 • years traveling over four continents, doing primary research to compile this unique book. -

Crowder, Enoch H., 1859-1932

Enoch H. Crowder Papers (C1046) Collection Number: C1046 Collection Title: Enoch H. Crowder Papers Dates: 1884-1942 Creator: Crowder, Enoch H., 1859-1932 Abstract: Correspondence and other papers of judge advocate general who administered Selective Service in World War I, served as ambassador to Cuba, and, after his retirement from public life, advised sugar interests. Collection Size: 27 cubic feet (2045 folders, 7 volumes; also available on 51 rolls of microfilm) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: Materials in this collection may be protected by copyrights and other rights. See Rights & Reproductions on the Society’s website for more information and about reproductions and permission to publish. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number Enoch H. Crowder Papers (C1046); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Columbia]. Donor Information: The papers were donated to the Western Historical Manuscript Collection by the University of Missouri Office of Public Information on November 21, 1955 (Accession No. CA3248). Additions were made on January 20, 1956 and November 6, 1958 by David Lockmiller (Accession Nos. CA3261 and CA3369) and on March 31, 1966 by the University of Missouri Library (Accession No. CA3658). (C1046) Enoch H. Crowder Papers Page 2 Alternate Forms Available: The Enoch H. -

The Fusion of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian Thought in the Republican Party of the 1920S

© Copyright by Dan Ballentyne 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This work is dedicated to my grandfather, Raymond E. Hough, who support and nurturing from an early age made this work possible. Also to my wife, Patricia, whose love and support got me to the finish line. ii REPUBLICANISM RECAST: THE FUSION OF HAMILTONIAN AND JEFFERSONIAN THOUGHT IN THE REPUBLICAN PARTY OF THE 1920S BY Dan Ballentyne The current paradigm of dividing American political history into early and modern periods and organized based on "liberal" and "conservative" parties does not adequately explain the complexity of American politics and American political ideology. This structure has resulted of creating an artificial separation between the two periods and the reading backward of modern definitions of liberal and conservative back on the past. Doing so often results in obscuring means and ends as well as the true nature of political ideology in American history. Instead of two primary ideologies in American history, there are three: Hamiltonianism, Jeffersonianism, and Progressivism. The first two originated in the debates of the Early Republic and were the primary political division of the nineteenth century. Progressivism arose to deal with the new social problems resulting from industrialization and challenged the political and social order established resulting from the Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian debate. By 1920, Progressivism had become a major force in American politics, most recently in the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson. In the light of this new political movement, that sought to use state power not to promote business, but to regulate it and provide social relief, conservative Hamiltonian Republicans increasingly began using Jeffersonian ideas and rhetoric in opposition to Progressive policy initiatives. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

![1935-02-05 [P A-5]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2364/1935-02-05-p-a-5-1472364.webp)

1935-02-05 [P A-5]

f on Stand Raises Blasts of the North LIFER'S FORM Kloppenburg All CLUES HELD Escape Wintry General Estimation of Bruno LEFT 10 GERMANS NOT CRIME-RIDDEN Picture of Hauptmann as Sociable and Schwarzkopf Summoned by Son of Rich Philadelphian Unpretentious Is Given to Jury—Story Capt. Rhoda Milliken Speaks Defense in Attack on Disinherits American of Package Left by Fisch Backed. to Manor Park Citizens’ Fingerprints. Kin in Odd Will. Association. BY ANNE GORDON SUYDAM. get eel traps with a friend could not Special Dispatch to The Star. murder a baby, and then snatch that Press. By the Associated Press. Washington is not the crime-ridden By the Associated N. 5.— same friend from his grave and sum- DANNEMORA, N. Y., February 5.— FLEMINGTON, J., February city many suppose it to be, Capt. FLEMINGTON, N. J„ February 5.— mon his shivering corpse In court for The State has bought a blue blanket For the first time since the defense Rhoda Milliken, chief of the Police Every available clue in the Lindbergh an alibi. and a wooden coffin for Alphonse J. opened its case Bruno Richard Haupt- Department's Woman’s Bureau, last baby kidnaping mystery led to "nobody Stephani, wealthy son of a Philadel- Personality May Shift. night told the Manor Park Citizens’ mann yesterday had a friend at court else but Hauptmann," Col. H. Norman phia wine merchant, who killed a Association at a “ladies’ night” cele- so his If Hauptmann, who laughed and Schwarzkopf, head of the New Jersey man 44 years ago and died in Danne- and a friend presentable that bration in the Whittier School. -

£H Ft Ssspji

FEB. 13.1933 THE INDIANAPOLIS TDIES PAGE 9 MORE THAN 100 WITNESSES TESTIFY IN BRUNO’S TRIAL STATE CHARGES HAUPTMANN The Artists Take a Peek at Fiemington CHIEF WITNESSES’ TESTIMONY WAS KIDNAPER, KILLER AND _ 4, I INill nlUtflMOST REVOLTINGIiLI ‘CRIME TAKER OF $50,000 RANSOM OF CENTURT IS REVIEWED Dav-by-Day Summary of Case Reveals Col. Lindbergh, Among First to Take Stand, Methods Used by Prosecution to Tie Recalls Events of Night When Blond Crime to Stolid German Carpenter. Child Is Stolen From Nursery. By United Pre,§ freii Bt tnliH A. Lindbergh—lie told of the events on the The steps by which the state of New Jersey built up its Col. Charles kidnaping, the empty crib, the ransom and murder case ajjainst Kruno Richard Hauptmann, and the night of the note outside. He heard a noise which efforts of the defense to combat the relentless piling up of the ladder found might evidence, are detailed in the have been a falling ladder, at about 9:15 p. m. on March 1, time of the kidnaping. The land- of following day-by-day sum- lord of Hauptmann's Bronx home but thought nothing it at board from the bearded and alert, testified he saw mary of the identifies a taken the time. He identified the trial: attic of the house, which the state Hauptmann drive past on March 1 and the "dirty WEDNESDAY. JAN. 2 says formed part of the ladder, the original ransom note in a green automobile" con- remainder having come from a lum- taining a ladder.