Reading Grade 3 and Grade 4 Classrooms in a California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Get There

USEFUL INFORMATION FOR VISITORS AND HOW TO REACH AEMET HEADQUARTERS AEMET Headquarters: How to get there AEMET’s address is Leonardo Prieto Castro, 8 within Ciudad Universitaria (University City), not far from Madrid downtown. It is located over a small hill behind the Faculty of Chemistry and can be easily identified by the big satellite antenna. Nearest Metro (underground railway) stations are Vicente Aleixandre and Ciudad Universitaria, both in Line 6 (the grey circular line). From these stations AEMET can be reached in about 10 minutes on foot. Buses G, 82, and 132 have stops at a 5 minutes walking distance from AEMET. These lines depart from Moncloa Square in front of the big building of the Air Force Headquarters (“Ejercito del Aire”), Metro station Moncloa (lines 3 & 6) is also there. Bus fare can be paid to the driver directly (1,50 €. No change given for more than 5€), or using a rechargeable card which are mandatory for the Metro. Rechargeable cards may be purchased at vending machines in the airport or every Metro station for 2.50 €. Then several tickets may be charged in the card. An airport Metro ticket costs 4.50 €. A 10 trips ticket for Metro or buses costs 12.20 € but is not valid for the airport. January 2020 USEFUL INFORMATION FOR VISITORS AND HOW TO REACH AEMET HEADQUARTERS How to reach downtown and AEMET Headquarters from the airport By Metro (underground railway) (recommended). Line 8 of “Metro” connects the airport with Nuevos Ministerios (final stop) the trip taking 15 minutes. Once in Nuevos Ministerios station, change to line 6 (5 minutes underground walk for this change). -

CIEMAT (Madrid, Spain)

FAIRMODE TECHNICAL MEETING 2019 Monday 7th – Wednesday 9th October 2019 CIEMAT (Madrid, Spain) Venue CIEMAT, Avenida Complutense 40. 28040, Madrid, Spain. Building 1. General map with venue, transportation and accommodation options (available on-line). An on-line version of this map is accesible at: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1pZNawnuOY3y2YZNu4CwpQTIAUL4&usp=sharing (CTRL+left click for opening). You can click on the markers of the on-line map to get further information (links to hotel websites). 1 Getting to CIEMAT/hotels By air Madrid-Barajas Airport (http://www.aeropuertomadrid-barajas.com/eng/home.html) is located at a 20-30 minutes ride by taxi (without traffic delays) from CIEMAT or accommodation options (fix price of 30€) or 50 minutes by metro (5 € one way). To come by metro you will need to take the line 8 in the airport Terminal 2 until “Nuevos Ministerios” station and connect with the ring line 6 until “Moncloa” or “Cuatro Caminos” or “Argüelles” stations for hotels or “Ciudad Universitaria” station for CIEMAT. Travel to/from the hotels to CIEMAT The venue can be reached by public transport using the metro line 6 stop “Ciudad Universitaria” plus a 20 minute walk through the campus (see map below) or by public bus, lines 82 from Moncloa (stops at Ciudad Universitaria metro station and CIEMAT) or F from Cuatro Caminos (stops at “Escuela Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicaciones”, 3 minutes walking to CIEMAT). Please consult the Google map above for locating the nearest stops between CIEMAT and hotels. Walk between the Ciudad Universitaria metro stop (line 6) and CIEMAT. -

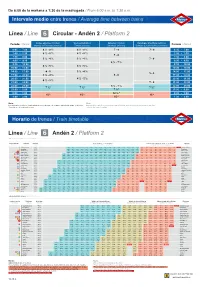

6 Circular - Andén 2 / Platform 2

De 6:00 de la mañana a 1:30 de la madrugada / From 6:00 a.m. to 1:30 a.m. Intervalo medio entre trenes / Average time between trains Línea / Line 6 Circular - Andén 2 / Platform 2 Lunes a jueves (minutos) Viernes (minutos) Sábados (minutos) Domingos y festivos (minutos) / Period / Period Período Monday to Thursday (minutes) Fridays (minutes) Saturdays (minutes) Sundays & public holidays (minutes) Período 6:05 - 7:00 4 ½ - 8 ½ 4 ½ - 8 ½ 7 - 9 7 - 9 6:05 - 7:00 7:00 - 7:30 4 ½ - 5 ½ 4 ½ - 5 ½ 7:00 - 7:30 7 - 8 7:30 - 9:00 7:30 - 9:00 3 ½ - 4 ½ 3 ½ - 4 ½ 7 - 8 9:00 - 9:30 9:00 - 9:30 6 ½ - 7 ½ 9:30 - 10:00 9:30 - 10:00 4 ½ - 5 ½ 4 ½ - 5 ½ 10:00 - 14:00 10:00 - 14:00 14:00 - 17:00 4 - 5 3 ½ - 4 ½ 14:00 - 17:00 5 - 6 17:00 - 20:00 3 ½ - 4 ½ 5 - 6 17:00 - 20:00 20:00 - 21:00 4 ½ - 5 ½ 20:00 - 21:00 4 ½ - 5 ½ 21:00 - 22:00 7 - 8 21:00 - 22:00 22:00 - 23:00 6 ½ - 7 ½ 22:00 - 23:00 7 ½* 7 ½* 7 ½* 23:00 - 0:00 7 ½* 23:00 - 0:00 0:00 - 1:00 12 ½ * 0:00 - 1:00 15 * 15 * 15 * 1:00 - 2:00 15 * 1:00 - 2:00 Nota: Note: Los intervalos medios se mantendrán de acuerdo con este cuadro, salvo incidencias en la línea. Average times will be in accordance with this table, unless there are incidents on the line. -

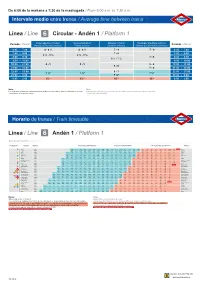

6 Circular - Andén 1 / Platform 1

De 6:00 de la mañana a 1:30 de la madrugada / From 6:00 a.m. to 1:30 a.m. Intervalo medio entre trenes / Average time between trains Línea / Line 6 Circular - Andén 1 / Platform 1 Lunes a jueves (minutos) Viernes (minutos) Sábados (minutos) Domingos y festivos (minutos) / Period / Period Período Monday to Thursday (minutes) Fridays (minutes) Saturdays (minutes) Sundays & public holidays (minutes) Período 6:05 - 7:00 4 - 8 ½ 4 - 8 ½ 7 - 9 7 - 9 6:05 - 7:00 7:00 - 9:00 7 - 8 7:00 - 9:00 2 ½ - 3 ½ 2 ½ - 3 ½ 9:00 - 9:30 7 - 8 9:00 - 9:30 6 ½ - 7 ½ 9:30 - 10:00 9:30 - 10:00 10:00 - 21:00 4 - 5 4 - 5 5 - 6 10:00 - 21:00 5 - 6 21:00 - 22:00 7 - 8 21:00 - 22:00 22:00 - 23:00 6 - 7 22:00 - 23:00 7 ½* 7 ½* 7 ½* 23:00 - 0:00 7 ½* 23:00 - 0:00 0:00 - 2:00 15 * 15 * 15 * 15 * 0:00 - 2:00 Nota: Note: Los intervalos medios se mantendrán de acuerdo con este cuadro, salvo incidencias en la línea. Average times will be in accordance with this table, unless there are incidents on the line. *Consúltese el horario de trenes. * Check the train timetable. Horario de trenes / Train timetable Línea / Line 6 Andén 1 / Platform 1 Todos los días a partir de las 22:00 horas / Every day from 10:00 p.m. Correspondencias Estaciones Primer tren Todos los días de 22:00 a 23:00 horas Todos los días de 23:00 a 24:00 horas Todos los días a partir de las 24:00 horas Estaciones Connections Stations First train All days from 10:00 p.m. -

Useful Information for Visitors and How to Reach the Headquarters of Aemet

USEFUL INFORMATION FOR VISITORS AND HOW TO REACH THE HEADQUARTERS OF AEMET Transport from Madrid airport to AEMET By Metro (underground railway) (Highly recommended). Line 8 of “Metro” connects the airport with Nuevos Ministerios (final stop) the trip taking 15 minutes. There are metro stations in Terminal 2, at walking distance from Terminals 1 & 3, and in Terminal 4. Trains depart every 5 minutes. Once in Nuevos Ministerios , change to line 6 (5 minutes underground walk for this change). It’s a circular line and you must take the westbound direction to the third station, Metropolitano, or the fourth, Ciudad Universitaria . Both stations are at 10 minutes walk to AEMET. See the map of the area on the images below, and the map of the Metro network among the attached links. The airport is in the upper right corner of the network. The Metro fare for a single ticket from the airport is 4.50 € (including airport supplement). By taxi . Regular taxis are available right outside the terminals. A run to the AEMET HQs can take 30 minutes in normal traffic conditions and the cost should be around 35 €. Transport from Madrid Airport to downtown Madrid By Metro (underground railway) (Highly recommended). Line 8 of “Metro” connects the airport with the rest of the Metro Network. There are metro stations in Terminal 2, at walking distance from Terminals 1 & 3, and in Terminal 4. Trains depart every 5 minutes. Line 8 ends at Nuevos Ministerios station in downtown Madrid, where you can transfer to other metro lines and other means of transportation. -

A Short Guide for Participants of the 15Th International Stellarator Workshop, 3Rd to 7Th October 2005

A Short Guide For Participants of the 15th International Stellarator Workshop, 3rd to 7th October 2005 The Local Organizing Committee is providing this short guide for participants. We hope that it will be useful to 15th International Stellarator Workshop participants. It gives information on how to get to and from the airport, Hotel Convencion and Ciemat as well as other details on the Workshop. There is also some basic eating out advice. We hope that it is of use to our guests. Registration Registration for the 15th International Stellarator Workshop will take place in the lobby of the Hotel Convencion between 4 and 8 pm on the Sunday afternoon. Registered participants will be provided with a badge for entering CIEMAT. There will also be the possibility to register at Ciemat on the Monday morning. However, as the Opening Ceremony begins at 8:45 am there will be little time to register many participants. Therefore the LOC would appreciate if all participants register on the Sunday afternoon in Hotel Convencion. Getting to Hotel Convencion from the Madrid Airport Madrid International Airport (at Barajas) is located 13 kilometres (eight miles) north east of central Madrid and provides a choice of convenient transport options to Hotel Convencion. By Metro First, Metro Line 8 (located in Terminal 2 of Madrid Airport) takes 12 minutes to Nuevos Ministerios. Tickets can be bought at automatic machines or from ticket desks in the station. The cost is 1 Euro for a single ride or 5.80 Euro for 10 rides. From Nuevos Ministerios take Line 6 to O’Donnell (this is a loop line so make sure to take the short way). -

Programa Upmmarch09

UPM ATHENS Programme March session 13-21/ 03 / 2009 Arrival: Students are expected to arrive in Madrid on Friday 13 th of March 2009 along the day. Information about how to reach the city is included. ↸↸↸ Accommodation has been booked in: La Posada de Huertas Calle Huertas 21, Madrid Phone: +34 91 429 55 26 Metro Station: Anton Martín. Line 1(light blue one) Exit: Antón Martín Students are expected to pay for the 8 night’s accommodation / per person 136€. (17 €. per night, breakfast is included) at arrival time. Check – in : Friday, 13th of March Check – out : Saturday 21st of March Cats Hostel Calle Cañizares 6, Madrid Phone: +34 91 3692807 Metro Station: Anton Martín. Line 1(light blue one) Exit: Calle Atocha Students are expected to pay for the 8 night’s accommodation / per person 136€. (17 €. per night, breakfast is included) at arrival time . Check – in : Friday, 13 th of March Check – out: Saturday 21 st of March Information on the Madrid metro system is available from: www.metromadrid.es 1 UPM ATHENS Programme March session 13-21/ 03 / 2009 HOW TO GO TO : La Posada de Huertas and Cats hostel. From the airport to the accommodation: Take the metro in the airport, line 8 (pink one) to Nuevos Ministerios. In Nuevos Ministerios change to line number 6 (grey one) to Pacífico station. In Pacífico station change to line number 1 (light blue one) to Antón Martín. This is the way you have to do only 2 changes. By metro is the faster and easier way to reach the hostel from the airport. -

GP Madrid 2017 Travel Guide

1- Introduction 2- Tournament Venue 3- Public Transportation System 4- Arriving f rom the airport 5- Hotels near the venue (and cheap accommodation) 6- Tourism (sites to visit) 7- Food and drink (dishes and restaurants) 8- Local Game Stores 9- Safety tips and contact information 10- Credits ¡BIENVENI DOS A MADRI D! Madrid is the capital of Spain and is located on the center of the country. More than three million people live in the city and six millions in the metropolitan area. A lot of this people are inmigrants and many spaniards are from elsewhere.That´s why people in Madrid are very friendly to fellow outsiders. It's widely agreed that you can be a "madrileño" without being born in Madrid! Not all the people can speak english, but they´ll try to help tourists with a bunch of words or by gestures. The history of Madrid is an odd one. An insignificant medieval city, it was only named capital in the 16th century and struggled to live up to the reputation of other great European hubs. Nowadays - finally - Madrid rests self assured with world class museums and architecture. Life in Madrid is made outdoor. Spaniards love social interactions, in bars, restaurants, clubs or in the street. The nightlife of Madrid is one of the craziest of Europe so you may find yourself until 6am moving from tapas bars to nightclubs surprised because the time has passed without noticing it. You'll find every imaginable kind of restaurants, dozens of cinemas, theaters and flamenco venues. If you're a sports fanatic, plan ahead to see one of the Best Football team of the 20th Century, Real Madrid CF, in action at the Bernabéu stadium. -

Madrid Visitor's Guide

Syracuse University Madrid´ VISITOR S GUIDE 2019 Edition Syracuse University Madrid C/ Miguel Angel, 8 28010 Madrid, Spain Tel: +34 913 199 942 Fax: +34 913 190 986 http://suabroad.syr.edu/madrid/ Madrid is enjoyed most from the ground, exploring your way through its narrow streets that always lead to some intriguing park, market, tapas bar or street performer. Emilio Estévez, U.S.-American actor Miro de frente y me pierdo en sus ojos sus arcos me vigilan, su sombra me acompaña no intento esconderme, nadie la engaña toda la vida pasa por su mirada. -“La puerta de Alcalá”, Ana Belén and Víctor Manuel Madrid is truly the city that never sleeps. With its bustling sidewalk cafes, museums, restaurants, neighborhood bars and pubs, you’ll never feel alone is this Mediterranean capital. After a few hours here, you’ll easily learn why your loved one has decided to call Madrid their second home. To help you navigate Madrid more easily, the SU Madrid staff has put together this guide which we hope will kick start you on your own aventura madrileña. ¡Hasta siempre! contents hotels 3-4 restaurants 5-6 pubs 7-8 museums 9-10 tours 11-12 shopping 13-14 faraday house area map 15 1 useful websites 16 1 Madrid is enjoyed most from the ground, exploring your way through its narrow streets that always lead to some intriguing park, market, tapas bar or street performer. Emilio Estévez, U.S.-American actor Miro de frente y me pierdo en sus ojos sus arcos me vigilan, su sombra me acompaña no intento esconderme, nadie la engaña toda la vida pasa por su mirada. -

Location Map from Moncloa Moncloa Is a Major Hub for Public Transport In

Workshop POSTDATA "Building a common model for semantic interoperability in the digital poetry ecosystems" 15th to 17th of March, Madrid Humanities Building UNED - Paseo Senda del Rey, 7 Madrid (Hall of policies and in rooms A and B Humanities Building). Location map From Moncloa Moncloa is a major hub for public transport in the capital, connected to the northwest of the Community of Madrid by many intercity bus lines and with the rest of the city by metro. Meter. The nearest metro stop to the UNED is called Moncloa and is part of the line 6 (circular), identifiable by its gray color. Plano Metro Once in Moncloa, you can reach the Hall of Economics (Senda del Rey, 11) in the following ways: Bus (15 -20 minutes approx.) This option includes all cases in at least a minimum length of 500 meters that has to be explored on foot. Bus A: Address Somosaguas, (2 stops: Stop Bridge of the French) Bus 161: E-Aravaca (4 stops: Stop Bridge of the French) Station Bus 46: Direction Principe Pio (3 stops: Stop Bridge of the French) A foot (23 minutes approx.) Paseo Ruperto Chapi King Street path Until Moncloa The shift from different points of the city to the Moncloa be done in the following ways: By train Madrid is connected to the other cities of the country by a wide railway network. The most important capital stations are Chamartin (North), Nuevos Ministerios, Sol (center) and Atocha (South), all connected with the underground network. Plane Madrid commuter trains. From Chamartin: Metro Line 1 (Cuatro Caminos), change to Line 6 (Moncloa) From Nuevos Ministerios: Metro Line 6 (Moncloa) Since Sun: Metro Line 3 (Moncloa) Bus 46 (from the c / Alcala / Granvia to stop the French Bridge) From Atocha (high speed lines): Line 1 (Sun), change to Line 3 (Moncloa) More information and schedules of different suburban lines here. -

GP Madrid 2016 Quick Guide

GP Madrid 2016 Quick Guide The goal of this Quick Guide is to have the most important information of the GP Guide in a single sheet of paper. Please print it, it can be extremely useful. Event Venue Address Pabellón Multiusos I (Madrid Arena) Recinto Ferial Casa de Campo Avenida de Portugal (entrance from Avenida Principal) 28011, Madrid, Spain Staff Hotel Address HOTEL CELUISMA FLORIDA NORTE **** Paseo de la Florida, 5 – 28008 Phone: +34 91 542 83 00 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency number: Use the purple branch if you are a judge in early shift Arriving from the Airport The best way to get there is to use the Metro, there are two Stations near the event venue: “Alto de Extremadura” Line 6 – Circular (Grey) and “Lago” Line 10 - Blue. To get there from the airport, the easiest way is to use the Metro: · Take Line 8 (Rose) to “Nuevos Ministerios” · Change to Line 6 – Circular (Grey) towards “Cuatro Caminos”. · Exit at “Alto de Extremadura”. It takes approximately 50 minutes to get to the station from Terminals T1 T2 T3, and 55 minutes from Terminal T4. Full map available herei Arriving from the Staff Hotel The best option is to use the Underground although you may also go on foot. Walk to Underground Station "Intercambiador de Príncipe Pío". Take the metro Line 6 to "Alto de Extremadura". Then follow the same instructions of "Arriving from the Airport". Need help?? RC Sergio Pérez [email protected] Local L3 Antonio José Rodríguez [email protected] Local L2 Aruna Prem Bianzino [email protected] Please, print this Quick Reference, and enjoy your GP!! J i http://www.metromadrid.es/export/sites/metro/comun/documentos/planos/Planoesquematicoingles.pdf . -

Syracuse University Madrid 2018 Edition

Syracuse University Madrid´ VISITOR S GUIDE 2018 Edition Syracuse University Madrid C/ Miguel Angel, 8 28010 Madrid, Spain Tel: +34 913 199 942 Fax: +34 913 190 986 http://suabroad.syr.edu/madrid/ Madrid is enjoyed most from the ground, exploring your way through its narrow streets that always lead to some intriguing park, market, tapas bar or street performer. Emilio Estévez, U.S.-American actor Miro de frente y me pierdo en sus ojos sus arcos me vigilan, su sombra me acompaña no intento esconderme, nadie la engaña toda la vida pasa por su mirada. -“La puerta de Alcalá”, Ana Belén and Víctor Manuel Madrid is truly the city that never sleeps. With its bustling sidewalk cafes, museums, restaurants, neighborhood bars and pubs, you’ll never feel alone is this Mediterranean capital. After a few hours here, you’ll easily learn why your loved one has decided to call Madrid their second home. To help you navigate Madrid more easily, the SU Madrid staff has put together this guide which we hope will kick start you on your own aventura madrileña. ¡Hasta siempre! contents hotels 3-4 restaurants 5-6 pubs 7-8 museums 9-10 tours 11-12 shopping 13-14 faraday house area map 15 1 useful websites 16 1 Madrid is enjoyed most from the ground, exploring your way through its narrow streets that always lead to some intriguing park, market, tapas bar or street performer. Emilio Estévez, U.S.-American actor Miro de frente y me pierdo en sus ojos sus arcos me vigilan, su sombra me acompaña no intento esconderme, nadie la engaña toda la vida pasa por su mirada.