Paulin Soumanou Vieyra (1925 - 1987)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Egyptian Gulf Blockade Starting at 11 A.M

y' y / l i , : r . \ ' < r . ■ « • - t . - FRroAY, MAY 26, 1987 FACE TWENTY-FOUR iianrtfifat^r lEn^nUts ll^ralb Average Daily Net Pi’ess Run The W eadier,;v 5 ; For The Week Ended Sunny, milder Pvt Ronald F. Oirouard, bon Presidents nnd Vice Presi May 20, 1067 65-70, clear and opol of Mrs. Josephine Walsh of Instruction Set dents, Mrs. Doris Hogan;, Secre- low about 40; moeOy fWr About Town 317 Tolland Tpke., and. Pvt Ray-Totten U TKTA IWbert Schuster; Joy n il. 1-iO U nC ll Treosurera, Geoige Dickie; Leg^ ' DAVIS BAKERY « mild ionfiorrow, taigta hi 70A The VFW Aiixlliexy has been Barry N. Smith, son of Mr. 15 ,2 1 0 and Mrs.' NeWton R. &nlth of islailve and Council Delegaites, ManOhenter—^A CUy, of Village Charm Invited to attend and bring the Tlie Mancheater PTA OouncU Lloyd Berry; Program, Mia. 32 S. Main St., have rec^ itly PRICE SEVEN CHM29 co lo n to the J<^nt installation ■wm sponsor a school of instruc- ca^riene- Taylor; Membership, (ClaMlfied Adverttsttit on Page IS) completed an Army advanced WILL BE CLOSED MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, MAY 27, 1967 « f oiTteers of the Glastonbury tion for incoming officers and Eleanor McBatai; PubUclty, VOL. LXXXVI, NO. 202 (SIXTEEN PAGES—TV SECTION) infantry course at F t Jackson, VPW Poet and AuxllttmT Sat ooenmittee members of Districts i^tonchester Hoiald staff; Ways S.C. M O N , MAY 29 S TUES,.IIAY 80 urday at 8 pjn. at the poet One an<| Two at Bowers School Means, Mot. -

Marcel Camus Ou O Triste Prévert Dos Trópicos

R V O Tunico Amancio Professor associado do curso de Cinema da Universidade Federal Fluminense. Pesquisador e curta-metragista. Marcel Camus ou o Triste Prévert dos Trópicos Marcel Camus fez três filmes de longa-metragem Marcel Camus made three feature films in no Brasil e com um deles – Orfeu do carnaval – Brazil and one of them – Orfeu do carnaval – ganhou fama internacional imediata. Seus outros made him instantly famous worldwide, while filmes passaram despercebidos do público e his other movies remained unnoticed by both da crítica. Taxados de folclóricos, exóticos, the audience and critics. Labeled as folkloric, ingênuos, românticos e alienados, trouxeram uma exotic, naive, romantic and alienated, they brought imagem do Brasil cheia de afeto e curiosidade, e us an image about Brazil full of affection and valem como testemunho de uma época e de um curiosity, and are a testimonial of an era and a olhar estrangeiro. foreigner’s look. Palavras-chave: olhar estrangeiro; Orfeu do carnaval; Keywords: foreign look; Orfeu do carnaval; Marcel Camus. Marcel Camus. omment être poète si message humaniste, briguant les lauriers on ne l’est pas? Telle est (chacun sa vérité) de Saint-Éxupery, il four- “C la quadrature du cercle nit un cinéma confiné de décors exotiques, qu’impose à cet aventurier appliqué le mais n’y déroule que de monotones péri- goût qu’ont des sambas les spectateurs péties de cartes postales: un triste Prévert européens; partagé entre le feuilleton et le sous les tropiques.”1 Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, no 1, p. 133-146, jan/jun 2010 - pág. -

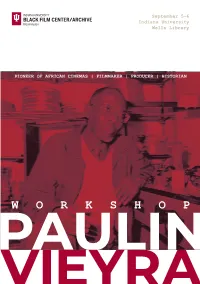

Paulin Vieyra Workshop 16 • Purpose • Speaker Topics • Participant Biographies • Sources

September 5-6 IndiAnA University Wells LibrAry PIONEER OF AFRICAN CINEMAS | FILMMAKER | PRODUCER | HISTORIAN WORKSHOP Program Thursday, September 5th 11:30-1:30 PM Ousmane Sembène Archives Pop-Up Exhibit Lilly Library Welcome Erika Dowell, Associate Director, Lilly Library Terri Francis, Director, Black Film Center/Archive 2-2:45 PM Introductions Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Participants briefy introduce themselves Keynote Vincent Bouchard (Moderator, Indiana University) Stéphane Vieyra, Presentation of Paulin S. Vieyra’s Archives 3-4:30 PM Vieyra, Filmmaker Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Akin Adesokan (Moderator, Indiana University) Rachel Gabara (University of Georgia) Samba Gadjigo (Mount Holyoke College) Sada Niang (University of Victoria) 5-7 PM Screenings Wells Library 048 • Afrique sur Seine (J.M. Kane, M. Sarr, Vieyra, 1955, 21min) • Une nation est née [A Nation is Born] (Vieyra, 1961, 25min) • Lamb (Vieyra, 1963, 18min) • Môl (Vieyra, 1966, 27min) • L’envers Du Décor [Behind the Scenes] (Vieyra, 1981, 16min) 26 Friday, September 6th 8:30 A M Coffee and snacks Black Film Center/Archive 9-10:30 AM Vieyra, Post-Colonial Intellectual Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Michael Martin (Moderator, Indiana University) Maguèye Kasse (Université Cheikh Anta Diop) Amadou Ouédraogo (University of Louisiana at Lafayette) Catherine Ruelle (Independent scholar) 11-1 PM Screening Wells Library 048 • En résidence surveillée [Under House Arrest] (Vieyra, 1981, 102min) 2:15-4 PM Vieyra, Historian and Producer Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Marissa Moorman (Moderator, Indiana University) Vincent Bouchard (Indiana University) Rachel Gabara (University of Georgia) Elena Razlogova (Concordia University) 4:30-7 PM Screening Wells Library 048 • L'envers du décor [Behind the Scenes] (P.S. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Marcel Camus: ORFEU NEGRO/BLACK ORPHEUS

Virtual Sept. 29, 2020 (41:5) Marcel Camus: ORFEU NEGRO/BLACK ORPHEUS (1959, 100m) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian video introduction to this week’s film Zoom link for all Fall 2020 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post- screening discussions: https://buffalo.zoom.us/j/92994947964?pwd=dDBWcDYvSlhP bkd4TkswcUhiQWkydz09 Meeting ID: 929 9494 7964 Passcode: 703450 Directed by Marcel Camus Written by Marcel Camus and Jacques Viot, based on the play Orfeu du Carnaval by Vinicius de Moraes . Produced by Sacha Gordine Original Music by Luiz Bonfá and Antonio Carlos Jobim Cinematography by Jean Bourgoin Film Editing by Andrée Feix spent the rest of his career directing TV episodes and mini- Production Design by Pierre Guffroy series. Breno Mello...Orfeo BRENO MELLO (September 7, 1931, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande Marpessa Dawn...Eurydice do Sul, Brazil – July 14, 2008, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Marcel Camus...Ernesto Sul, Brazil) appeared in only five other films: 1988 Prisoner of Fausto Guerzoni...Fausto Rio, 1973 O Negrinho do Pastoreio, 1964 O Santo Módico, Lourdes de Oliveira...Mira 1963 Os Vencidos, and 1963 Rata de Puerto. Léa Garcia...Serafina Ademar Da Silva...Death MARPESSA DAWN (January 3, 1934, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Alexandro Constantino...Hermes – August 25, 2008, Paris, France) appeared in 17 other films, Waldemar De Souza...Chico among them 1995 Sept en attente, 1979 Private Collections, Jorge Dos Santos...Benedito 1973 Lovely Swine, 1958 The Woman Eater and 1957 Native Aurino Cassiano...Zeca Girl. -

Tournées Film Festival

TOURNÉES FILM FESTIVAL FRENCH FILMS ON CAMPUS 2020/2021 TOURNÉES FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL TOURNÉES face-foundation.org/tournees-film-festival by: is made possible Film Festival Tournées Embassy of the French Services with the Cultural in collaboration Foundation of FACE is a program Film Festival Tournées TABLE OF CONTENTS Presentation Eligibility and Guidelines Featured Film Selection CASSANDRO, THE EXOTICO! / CASSANDRO, THE EXOTICO! / 6 CHAMBRE 212 / ON A MAGICAL NIGHT / 7 DILILI À PARIS / DILILI IN PARIS / 8 L’EXTRAORDINAIRE VOYAGE DE MARONA / MARONA’S FANTASTIC TALE / 9 FUNAN / FUNAN / 10 GRÂCE À DIEU / BY THE GRACE OF GOD / 11 JEANNE / JOAN OF ARC / 12 NE CROYEZ SURTOUT PAS QUE JE HURLE / JUST DON’T THINK I’ILL SCREAM / 13 O QUE ARDE / FIRE WILL COME / 14 PORTRAIT DE LA JEUNE FILLE EN FEU / PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE / 15 PREMIÈRE ANNÉE / THE FRESHMEN / 16 LE PROCÈS DE MANDELA ET LES AUTRES / THE STATE AGAINST MANDELA AND THE OTHERS / 17 SIBYL / SIBYL / 18 SYNONYMS / SYNONYMS / 19 TOUT EST PARDONNÉ / ALL IS FORGIVEN / 20 UN FILM DRAMATIQUE / A DRAMATIC FILM / 21 VARDA PAR AGNÈS / VARDA BY AGNES / 22 LA VÉRITÉ / THE TRUTH / 23 Alternative Film Selection Classic Film Selection L’AMI DE MON AMIE / BOYFRIENDS & GIRLFRIENDS / 25 AFRIQUE SUR SEINE / AFRICA ON THE SEINE, LAMB / LAMB, UNE NATION EST NÉE / A NATION WAS BORN, L’ENVERS DU DÉCOR / L’ENVERS DU DÉCOR / 26 LA FEMME DE L’AVIATEUR / THE AVIATOR’S WIFE / 27 HYÈNES / HYENAS / 28 MR. KLEIN / MR. KLEIN / 29 LE MYSTÈRE PICASSO / THE MYSTERY OF PICASSO / 30 SOLEIL Ô / SOLEIL Ô / 31 Distributors Campus France USA Franco-American Cultural Fund CREDITS Cover image from Portrait of a Lady on Fire, courtesy of NEON. -

Ollie Stewart: an African American Looking at American Politics, Society and Culture

Ollie Stewart: An African American Looking at American Politics, Society and Culture by Jinx Coleman Broussard [email protected] Associate Professor, Manship School of Mass Communication Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge & Newly Paul [email protected]. Doctoral Student, Manship School of Mass Communication Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge Abstract This article examines and interprets the writings of Ollie Stewart, the Paris-based foreign correspondent for the Afro-American newspaper from 1949 to 1977. The articles and lively columns this expat journalist wrote during the post-World War II period when the black press was in decline, provided his and foreigners’ views about some of the seminal events that were shaping America and directly impacting Blacks throughout the world. Though at one point he was the only Black correspondent reporting continually reporting from abroad, he has largely been invisible in media history. This article aims to fill this gap. Using framing theory approach and textual analysis, this article examines how Stewart addressed race, U.S. foreign policy, politics and the achievements and activities of Blacks abroad. Stewart’s writing provided information and viewpoints that were largely excluded from mainstream media and filled an important void in the press and American history. 228 The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.6, no.8, March 2014 Ollie Anderson Stewart was one of at least twenty-seven African-American correspondents who covered Black troops during World War II from all theatres. Like the other Black war correspondents, Stewart wrote about the valor and success of the fighter pilots now known as the Tuskegee Airmen. -

The Foreign Service Journal, February 2005

FIXING FS EVALUATIONS I COLD WAR ECHOES I TAKE A PUNDIT TO WORK? 2004 TAX GUIDE INSIDE! $3.50 / FEBRUARY 2005 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S THE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS FROM COLIN TO CONDI: The Handoff at State In Re: Personal Banking from Overseas (Peace of Mind Is at Hand!) Dear Journal Reader: There are many exciting experiences while on overseas assignment, but managing your finances isn’t typi- cally one of them. Actually, it can be quite challenging.Managing your pay, meeting financial obligations, maintaining a good credit rating at home, and sustaining and growing one’s financial portfolio can all become a challenge. Additionally, once settled-in at your country of assignment, local obligations arise, requiring the need to transfer funds, be it in US Dollars or in Foreign Currency. A seamless solution exists, which not only provides all of the necessary tools to efficiently manage your Personal Banking but, more importantly, provides “Peace of Mind.” The Citibank Personal Banking for Overseas Employees (PBOE) program delivers this Peace of Mind and so much more. Citibank PBOE has been the provider of choice and industry leader servicing inter- national assignees for over a third of Citibank’s century-plus history. Citibank PBOE offers a product and solution set designed specifically for the client on overseas assignment. Citibank PBOE provides a simpli- fied, practically paperless way to manage your Banking by establishing a comprehensive, globally accessi- ble banking relationship that includes access to credit and also to alternative banking products and ser- vices. -

![BLACK ORPHEUS [ORFEU NEGRO] France/Brazil, Marcel Camus, 1959](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9780/black-orpheus-orfeu-negro-france-brazil-marcel-camus-1959-4159780.webp)

BLACK ORPHEUS [ORFEU NEGRO] France/Brazil, Marcel Camus, 1959

BLACK ORPHEUS [ORFEU NEGRO] France/Brazil, Marcel Camus, 1959 Cast: Director: Marcel Camus Breno Mello ... Orfeo Length: 105 minutes Marpessa Dawn ... Eurydice Country: France/Brasil Marcel Camus ... Ernesto Producer: Sacha Gordine Fausto Guerzoni ... Fausto Language: Portuguese Lourdes de Oliveira … Mira Color: Color Léa Garcia ... Serafina Script: Marcel Camus, Jacques Viot, Vinicius de Moraes Ademar Da Silva ... Death Photography: Jean Bourgoin Alexandro Constantino ... Hermes Editing: Andrée Feix Waldemar De Souza ... Chico Music by Luiz Bonfá, Antonio Carlos Jobim Jorge Dos Santos ... Benedito Aurino Cassiano ... Zeca Questions of Analysis: 1. What is this movie about? 2. How does the opening scene sets the enigma for the remaining of the movie. 3. What is the meaning of the title? 4. What does the audience need to know to better understand the film? 5. Whose story is it? Defend your answer. 6. Identify the basic conflict and provide a list of metaphors. 7. Whose perspective does the film use to deliver the story? 8. What is the film's and the directors's ideology? 9. How does the film portray the Brazilian spaces? 10. How does Black Orpheus present religion as “social construct”? 11. Explore the religious topics presented in the film as it transforms a classical Greek mythology story into a Brazilian favela carnival/urban story 12. How is syncretism presented in the film? 13. Interpret syncretism from within the Afro-Brazilian point of view (See Bastide's article). 14. What is the role of religion in the culture depicted in the film? 15. What is the director's purpose for making this film? 16. -

B Fi S O Uth Ba

w MUSICALS! THE GREATEST SHOW ON SCREEN MED HONDO MAURICE PIALAT FESTIVE FAVOURITES THE UMBRELLAS OF CHERBOURG SOUTHBANK BFI DEC 2019 THE NURI BILGE CEYLAN BLU-RAY BOX SET By any reckoning Nuri Bilge Ceylan is one of the world’s foremost filmmakers. The box set contains all 8 of his feature films to date, an early short, Koza, plus interviews and behind the scenes documentaries. Kasaba, Clouds of May, Uzak, Climates and Three Monkeys are all appearing on Blu-ray for the first time. The discs of Kasaba, Clouds of May, Uzak and Climates are region-free. The others are region B. RELEASE DATE 28TH OCTOBER www.newwavefilms.co.uk Nuri Bilge Ceylan BFI ad.indd 1 01/10/2019 15:00 THIS MONTH AT BFI SOUTHBANK THE NURI BILGE CEYLAN BLU-RAY BOX SET Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with a world-class library, free exhibitions and Mediatheque and plenty of food and drink By any reckoning Nuri Bilge Ceylan is one IN PERSON & PREVIEWS RE-RELEASES SEASONS Talent Q&As and rare appearances, plus a chance Key classics (many newly restored) for you to enjoy, with plenty of Carefully curated collections of film of the world’s foremost filmmakers. for you to catch the latest film and TV before screening dates to choose from and TV, which showcase an influential anyone else genre, theme or talent The box set contains all 8 of his feature films to date, an early short, Koza, (p34) plus interviews and behind the scenes (p13) documentaries. (p7) Kasaba, Clouds of May, Uzak, Climates and Three Monkeys are all appearing on Blu-ray for the first time. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1963-07-02

~ Post Rainum! Palmer Wins CI,ar to partly cloudy today and tonltht. Chence of widely Katterecl show.rs or thunderstorm. .x· See Story, Page 4 ~ 01 owon tNtM SOIIth. Hiths 80s northw ..t to Mar " .x. Serving the State University of Iowa and the People of Iowa City trtml southu.t. Established in 1868 10 Cents Per Copy Associated Press Leased Wires and Wirephoto Iowa City, Iowa, Tuesday, July 2, 1963 Regents Approve U.S. Expels As 73 Gain Rank Red Diplomat Rai.n Co'mes To City In Washington In SUI Promciltions Reported Trying To Get CIA Employe Blacks Out Promotions of 73 SUI (acully Marvin Thostensen, all music; members Lo the ranks of professor Norval Tucker and RoberL L. Alex To Spy for Russia and associate professor were ap · onder. art; Christopher La ch, his WASHINGTON (11'1 - The United proved here Friday by the State tory, Edwin B. Allaire Jr., philo States Monday ordered the ex Board of Regents . sophy; Ed~in Norbeck, physics pulsion of a Soviet diplomat. It an Twenty-six of the faculty mem- an~~stron0!l1Y; Robert P. Boy~ton , nounced he had been caught red bers were promoted to full profes- I pollbcal s~lence; Job~ O. CrItes, handed trying to recruit a U.S. sorsbips and 47 were made associ. psychology, Mrs ..Jessle G. Horns- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) By TIM CALLAN te professors. by and Margueflte lkn~yan , ro- employe to spy for the Soviet Un a mance languages; Merlm Tabor, City Editor Pr.omoted to the rank. of profes- social work; June Helm, sociology ion. -

04 Santos (Jr/T) 11/7/03 9:39 Am Page 49

04 Santos (jr/t) 11/7/03 9:39 am Page 49 The Brazilian Remake of the Orpheus Legend: Film Theory and the Aesthetic Dimension Myrian Sepúlveda dos Santos Films and other forms of visual experience have become central issues for investigation in contemporary societies. From Simmel’s emphasis on the precedence of visual experience in modern life to more recent explorations of new media of communication and entertainment, figural forms have been increasingly investigated. In addition, former concerns about hegemonic productions of the cultural industry or manipulative forms of popular leisure have been replaced by investigations that consider the products of the cultural industry in general as signifying practices. This article takes these recent contributions as its point of departure and investigates two Brazilian films that are based on the Greek Orpheus legend. The films are adaptations of the play Orfeu da Conceição, written by the Brazilian poet and songwriter Vinícius de Moraes in 1956. The play reconfigures one of the most cherished myths of Western civilization about the very essence of musicality: the Greek legend of Orpheus. Moraes inter- twined in his play Orpheus’ eternal musical powers, the tragic story of love and passion between Orpheus and Eurydice, and the carnival festivities of the city of Rio de Janeiro. The story is set in a shantytown and on the streets of Rio, which are shown to be inhabited by a mostly black population. Films are marked by elements of the historical periods in which they were created. The two remakes of the play belong to two different historical contexts.