04 Santos (Jr/T) 11/7/03 9:39 Am Page 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nov 2014 Dummy.Indd

NOVEMBERJULY 20102014 •• TAXITAXI INSIDERINSIDER •• PAGEPAGE 11 INSIDER VOL. 15, NO. 11 “The Voice of the NYC Transportation Industry.” NOVEMBER 2014 Letters Start on Page 3 EDITORIAL • By David Pollack Insider News Page 5 • Taxi Drivers and Ebola Updated Relief Stands Thankfully there is a radio show where you can Taxi Dave (that’s me!) not only had the Chairwoman get fi rst hand information needed to answer any of of the TLC, Meera Joshi discuss fears of the Ebola Page 6 your questions whether industry related or even virus, but I had Dr. Jay Varma, a spokesperson from • health related. the NYC Department of Health answering all ques- Taxi Attorney Before we get into Ebola, TLC Chair- tions that drivers brought to “Taxi Dave’s” By Michael Spevack woman Joshi stated that the TLC will attention. How does Ebola spread? What be sending out warning letters to drivers is the best means of prevention and pro- Page 7 instead of summonses for a red light tection? • camera offense. “Vision Zero is not Chairwoman Joshi stated, “Thank you How I Became A Star about penalties,” she stated. To hear this for reaching out to the Department of By Abe Mittleman and much more, listen to this link: http:// Health. The myth of how Ebola spreads is www.wor710.com/media/podcast-the- spreading incredibly faster than the actual Page 15 taxi-dave-show-TaxiInsider/the-taxi-dave- disease ever could. It is really important to • show-102614-25479519/ separate facts from fi ction and the Depart- Street Talk Folks, if you want fi rst hand infor- ment of Health has been doing an amazing By Erhan Tuncel mation, every Sunday evening at 8:00 job in getting that message out there and PM listen to WOR-710 radio to TAXI DAVE. -

Sky-High Landmark District

BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Brooklyn Heights Paper, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, DUMBO Paper, Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper and Downtown News Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages •Vol.28, No. 10 BWN • Saturday, March 5, 2005 • FREE SKY-HIGH BKLYN STATE SENATOR TO CITY: LANDMARK DISTRICT Heights civics seek to protect buildings near Borough Hall By Jess Wisloski buildings or larger complexes The Brooklyn Papers under the Downtown Brooklyn Rezoning Plan approved last With the help of a preserva- summer. tion group, the Brooklyn “These are very distin- Heights Association is pro- guished commercial buildings moting a plan to preserve sev- built by the best architects of eral high-rise office buildings the day,” said Herrera, technical just outside the Brooklyn services director of the Land- Heights Historic District. marks Conservancy. Herrera Calling it the “Borough Hall said the movement came about Skyscraper Historic District,” after St. Francis College began BHA President Nancy Bowe demolition of the McGarry Li- touted the proposal at her brary last year at 180 Remsen group’s annual meeting last St. month. “Some of them have been The compact district would abused and knocked around, “butt up against” the Brooklyn but they could be restored and Heights Historic District, ac- really bought back to their cording to the proposal’s coor- best,” he said, and called the dinator, BHA governor Alex proposed district a “real history Showtime Herrera, who also works for the lesson” on the days when “the New York Landmarks Conser- best architects in New York vancy. -

He Dreams of Giants

From the makers of Lost In La Mancha comes A Tale of Obsession… He Dreams of Giants A film by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe RUNNING TIME: 84 minutes United Kingdom, 2019, DCP, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, Aspect Ratio16:9 PRESS CONTACT: Cinetic Media Ryan Werner and Charlie Olsky 1 SYNOPSIS “Why does anyone create? It’s hard. Life is hard. Art is hard. Doing anything worthwhile is hard.” – Terry Gilliam From the team behind Lost in La Mancha and The Hamster Factor, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is the culmination of a trilogy of documentaries that have followed film director Terry Gilliam over a twenty-five-year period. Charting Gilliam’s final, beleaguered quest to adapt Don Quixote, this documentary is a potent study of creative obsession. For over thirty years, Terry Gilliam has dreamed of creating a screen adaptation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. When he first attempted the production in 2000, Gilliam already had the reputation of being a bit of a Quixote himself: a filmmaker whose stories of visionary dreamers raging against gigantic forces mirrored his own artistic battles with the Hollywood machine. The collapse of that infamous and ill-fated production – as documented in Lost in La Mancha – only further cemented Gilliam’s reputation as an idealist chasing an impossible dream. HE DREAMS OF GIANTS picks up Gilliam’s story seventeen years later as he finally mounts the production once again and struggles to finish it. Facing him are a host of new obstacles: budget constraints, a history of compromise and heightened expectations, all compounded by self-doubt, the toll of aging, and the nagging existential question: What is left for an artist when he completes the quest that has defined a large part of his career? 2 Combining immersive verité footage of Gilliam’s production with intimate interviews and archival footage from the director’s entire career, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is a revealing character study of a late-career artist, and a meditation on the value of creativity in the face of mortality. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Of Egyptian Gulf Blockade Starting at 11 A.M

y' y / l i , : r . \ ' < r . ■ « • - t . - FRroAY, MAY 26, 1987 FACE TWENTY-FOUR iianrtfifat^r lEn^nUts ll^ralb Average Daily Net Pi’ess Run The W eadier,;v 5 ; For The Week Ended Sunny, milder Pvt Ronald F. Oirouard, bon Presidents nnd Vice Presi May 20, 1067 65-70, clear and opol of Mrs. Josephine Walsh of Instruction Set dents, Mrs. Doris Hogan;, Secre- low about 40; moeOy fWr About Town 317 Tolland Tpke., and. Pvt Ray-Totten U TKTA IWbert Schuster; Joy n il. 1-iO U nC ll Treosurera, Geoige Dickie; Leg^ ' DAVIS BAKERY « mild ionfiorrow, taigta hi 70A The VFW Aiixlliexy has been Barry N. Smith, son of Mr. 15 ,2 1 0 and Mrs.' NeWton R. &nlth of islailve and Council Delegaites, ManOhenter—^A CUy, of Village Charm Invited to attend and bring the Tlie Mancheater PTA OouncU Lloyd Berry; Program, Mia. 32 S. Main St., have rec^ itly PRICE SEVEN CHM29 co lo n to the J<^nt installation ■wm sponsor a school of instruc- ca^riene- Taylor; Membership, (ClaMlfied Adverttsttit on Page IS) completed an Army advanced WILL BE CLOSED MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, MAY 27, 1967 « f oiTteers of the Glastonbury tion for incoming officers and Eleanor McBatai; PubUclty, VOL. LXXXVI, NO. 202 (SIXTEEN PAGES—TV SECTION) infantry course at F t Jackson, VPW Poet and AuxllttmT Sat ooenmittee members of Districts i^tonchester Hoiald staff; Ways S.C. M O N , MAY 29 S TUES,.IIAY 80 urday at 8 pjn. at the poet One an<| Two at Bowers School Means, Mot. -

Marcel Camus Ou O Triste Prévert Dos Trópicos

R V O Tunico Amancio Professor associado do curso de Cinema da Universidade Federal Fluminense. Pesquisador e curta-metragista. Marcel Camus ou o Triste Prévert dos Trópicos Marcel Camus fez três filmes de longa-metragem Marcel Camus made three feature films in no Brasil e com um deles – Orfeu do carnaval – Brazil and one of them – Orfeu do carnaval – ganhou fama internacional imediata. Seus outros made him instantly famous worldwide, while filmes passaram despercebidos do público e his other movies remained unnoticed by both da crítica. Taxados de folclóricos, exóticos, the audience and critics. Labeled as folkloric, ingênuos, românticos e alienados, trouxeram uma exotic, naive, romantic and alienated, they brought imagem do Brasil cheia de afeto e curiosidade, e us an image about Brazil full of affection and valem como testemunho de uma época e de um curiosity, and are a testimonial of an era and a olhar estrangeiro. foreigner’s look. Palavras-chave: olhar estrangeiro; Orfeu do carnaval; Keywords: foreign look; Orfeu do carnaval; Marcel Camus. Marcel Camus. omment être poète si message humaniste, briguant les lauriers on ne l’est pas? Telle est (chacun sa vérité) de Saint-Éxupery, il four- “C la quadrature du cercle nit un cinéma confiné de décors exotiques, qu’impose à cet aventurier appliqué le mais n’y déroule que de monotones péri- goût qu’ont des sambas les spectateurs péties de cartes postales: un triste Prévert européens; partagé entre le feuilleton et le sous les tropiques.”1 Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, no 1, p. 133-146, jan/jun 2010 - pág. -

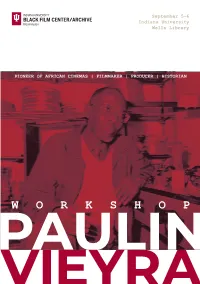

Paulin Vieyra Workshop 16 • Purpose • Speaker Topics • Participant Biographies • Sources

September 5-6 IndiAnA University Wells LibrAry PIONEER OF AFRICAN CINEMAS | FILMMAKER | PRODUCER | HISTORIAN WORKSHOP Program Thursday, September 5th 11:30-1:30 PM Ousmane Sembène Archives Pop-Up Exhibit Lilly Library Welcome Erika Dowell, Associate Director, Lilly Library Terri Francis, Director, Black Film Center/Archive 2-2:45 PM Introductions Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Participants briefy introduce themselves Keynote Vincent Bouchard (Moderator, Indiana University) Stéphane Vieyra, Presentation of Paulin S. Vieyra’s Archives 3-4:30 PM Vieyra, Filmmaker Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Akin Adesokan (Moderator, Indiana University) Rachel Gabara (University of Georgia) Samba Gadjigo (Mount Holyoke College) Sada Niang (University of Victoria) 5-7 PM Screenings Wells Library 048 • Afrique sur Seine (J.M. Kane, M. Sarr, Vieyra, 1955, 21min) • Une nation est née [A Nation is Born] (Vieyra, 1961, 25min) • Lamb (Vieyra, 1963, 18min) • Môl (Vieyra, 1966, 27min) • L’envers Du Décor [Behind the Scenes] (Vieyra, 1981, 16min) 26 Friday, September 6th 8:30 A M Coffee and snacks Black Film Center/Archive 9-10:30 AM Vieyra, Post-Colonial Intellectual Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Michael Martin (Moderator, Indiana University) Maguèye Kasse (Université Cheikh Anta Diop) Amadou Ouédraogo (University of Louisiana at Lafayette) Catherine Ruelle (Independent scholar) 11-1 PM Screening Wells Library 048 • En résidence surveillée [Under House Arrest] (Vieyra, 1981, 102min) 2:15-4 PM Vieyra, Historian and Producer Wells Library 044B – Phyllis Klotman Room Marissa Moorman (Moderator, Indiana University) Vincent Bouchard (Indiana University) Rachel Gabara (University of Georgia) Elena Razlogova (Concordia University) 4:30-7 PM Screening Wells Library 048 • L'envers du décor [Behind the Scenes] (P.S. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Quentin Couldn't

The Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus, for April 13th through April 19th. 1995 Quentin couldn't: make it, but we got the inside scoop» on Destiny- Turns on tJie Ftedio from his co-stars Dylan McDermott and Nancy Travis, along with director Jack Bar an. See pages 4A-5A. 2A Thursday, April 13,1993 Daily Nexus bars of cage / you see scars, much ease — thus “Strug results of my rage.” That’s glin’,” tire soul food, hip- another thing about this hop blues, demi-epic of debut album. In Tricky’s the album. (The “epic” Massive and Unparalleled world, everything is a cage, track would probably be without any hope of re the seven-minute exten prieve. Even love is a sti sion of their first single, T ricky posedly one of 'fricky’s landic woman named any of them out from the fling, repressive activity “Aftermath.”) Amid creak M axinquaye nonsense words, sort of Ragga (again, no last scrapyard beats, hip-hop and sex is the violent ing doors, screeching 4th S t Broadway/I gland based around the name of name) and Alison Gold- breaks, soul slides and means of expressing one’s saxes, cocking rifles and his mother. frapp, who was most re thick, dark atm osphere anger. ambulance wails, Tricky This is almost too dense While we’re on names, cently heard on Orbital’s that just oozes out all over Witness “Abbaon Fat mutters like a junkie com a record for one head to Tricky’s real one is Adrian last album. -

PELLE the CONQUEROR (Pelle Erobreren) Directed by Bille August

presents A 30th Anniversary Restoration PELLE THE CONQUEROR (Pelle erobreren) Directed by Bille August “[T]he film is a towering achievement…an exhilarating experience unlikely to be forgotten.” – Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times Denmark, Sweden / 1987 / Drama / Danish and Swedish with English subtitles 157 min / 1.66: 1 / 2K scan from original 35mm negative Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | Press | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier |Theatrical Booking | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] Assets: Official Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wIoZ5OYc9RE Downloadable hi-res images: http://www.filmmovement.com/filmcatalog/index.asp?MerchandiseID=537 SELECT PRESS "The von Sydow performance is in a category by itself. It is another highlight in an already extraordinary career, and quite unlike anything that American audiences have seen him do to date." – Vincent Canby, New York Times “Visually speaking, the film is handsome….Then again, perhaps the real secret to PELLE’s demographic-crossing appeal is the presence of the great von Sydow…” – A.A. Dowd, AV Club “In Bille August's PELLE THE CONQUEROR, Max von Sydow is so astoundingly evocative that he makes your bones ache.” – Hal Hinson, The Washington Post “The film is a richness of events….there is not a bad performance in the movie, and the newcomer, Pelle Hvenegaard, never steps wrong in the title role....It is Pelle, not Lasse, who is really at the center of the movie, which begins when he follows his father’s dream, and ends as he realizes he must follow his own.” – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com SYNOPSIS Lasse (Max von Sydow), an elderly and widowed farmer, and his young son Pelle join a boat-load of immigrants to escape from impoverished rural Sweden to Denmark's Baltic island of Bornholm. -

Timeline of Selected Bergman 100 Events

London, 18.09.17 Timeline of selected Bergman 100 events This timeline includes major activities before and during the Bergman year. Please note that there are many more events to be announced both within this timeframe and beyond. A full, regularly updated calendar of performances, retrospectives, exhibitions and other events is available at www.ingmarbergman.se September 2017 • Misc.: Launch of Bergman 100, 18 Sep, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 31 Aug, Det Kgl Teater (The Royal Playhouse), Copenhagen, Denmark. • On stage: Autumn Sonata (opera), opening 8 Sep, Finnish National Opera, Helsinki, Finland. • Book release: Ingmar Bergman A–Ö (in English), Ingmar Bergman Foundation/Norstedts publishing, Sweden. • On stage: The Best Intentions, opening 16 Sep, Aarhus theatre, Aarhus, Denmark. • On stage: After the Rehearsal/Persona, The Barbican, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 20 Sep, Teatros del Canal, Madrid, Spain. • On stage: Breathe, Bergman-inspired dance performance, opening 28 Sep, Inkonst, Malmö, Sweden. • On stage: The Serpent’s Egg, opening 30 Sep, Cuvilliés-Theater, Munich, Germany. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, world tour Sep–Dec, Asia, Europe, South America. October 2017 • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 5 Oct, Ernst-Deutsch-Theater, Hamburg, Germany. • On stage: After the rehearsal, opening 20 Oct, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, Düsseldorf, Germany. • Misc.: The European Film Academy awards Hovs Hallar the title ‘Treasure of European Film Culture’. (A nature reserve in the county of Skåne, Sweden, Hovs Hallar is the location of the chess scene in The Seventh Seal.) • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 25 Oct, Teatro Tivoli, Barcelona, Spain.