Detailed Species Accounts from the Threatened

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History, Development and Corporate Structure

THE DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” OF THE COVER OF THE DOCUMENT. HISTORY, DEVELOPMENT AND CORPORATE STRUCTURE OVERVIEW We are a leading ready-mixed concrete producer in China with strong research and development capabilities according to the CIC Report. Our history can be traced back to YNJG Concrete, which was established in April 1996. Its principal businesses included the production and sales of commercial concrete and related products. After being merged and absorbed into YNJG as the Commercial Concrete Division through an asset restructuring, YNJG Concrete was deregistered in May 2012. In December 2016, YNJG injected the operating assets of the Commercial Concrete Division and the equity interests of four operating subsidiaries into the Company through a capital increase. On June 19, 2007, the Company was established as a limited liability company by YNJG Concrete. On December 22, 2017, the Company was converted into a joint stock limited company and renamed “YCIH Green High-Performance Concrete Company Limited.” MILESTONES The following table outlines the milestones in our history of development: Years Events 1996 YNJG Concrete was established, whose principal businesses included the production and sales of commercial concrete and related products. 2007 The Company was established by YNJG Concrete in Kunming, Yunnan Province as a limited liability company, i.e., YNJG Green High- Performance Concrete Co., Ltd. (雲南建工綠色高性能混凝土有限公司). 2007 YNJG Concrete undertook the project of concrete production and supply for “Kunming University Town (昆明大學城)”, and from 2007 to 2010, it produced and supplied more than 800,000 cubic meters of concrete for this project. -

Kunming Qingshuihai Water Supply Project

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors ````````````````````````````````````````````````````````Sri Lanka Project Number: 40052 November 2007 Proposed Loan People’s Republic of China: Kunming Qingshuihai Water Supply Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 November 2007) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1347 $1.00 = CNY7.43 ABBREVIATIONS AAOV – average annual output value ADB – Asian Development Bank AH – affected household AP – affected person ASEAN – Association of Southeast Asian Nations EDZ – East Development Zone EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMDP – ethnic minority development plan EMP – environmental management plan FYP – five-year program GDP – gross domestic product IA – implementing agency ICB – international competitive bidding JBIC – Japan Bank for International Cooperation JV – joint venture KMG – Kunming municipal government KWSG – Kunming Water Supply Group Company Limited LIBOR – London interbank offered rate MDG – Millennium Development Goal MLSS – minimum living standard scheme NADZ – New Airport Development Zone NCB – national competitive bidding O&M – operation and maintenance PLG – project leading group PMO – project management office PPMS – project performance monitoring system PRC – People’s Republic of China PSP – private sector participation QCBS – quality- and cost-based selection RP – resettlement plan SEPA – State Environmental Protection Administration TA – technical assistance WACC – weighted average cost of capital WSC – water supply company WWTP – wastewater treatment plant YPG – Yunnan provincial government WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km2 – square kilometer m2 – square meter m3 – cubic meter m3/s – cubic meter per second mu – unit of land measure, 667 m2 NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government ends on 31 December. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY 2007 ends on 31 December 2007. -

6. Estimates of Compensation Fees for Land Acquisition and House Demolition

RP895 V1 Public Disclosure Authorized Zhaotong Central City Environmental Construction Project Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Management Office of Foreign-funded Urban Construction Projects of Zhaoyang District, Zhaotong Municipality Resettlement Office of World Bank Financed Zhaotong Central City Environmental Construction Project Zhaotong, China, November 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Summary A. Overview 1. The Zhaotong Central City Environmental Construction Project (hereinafter referred to as the “Project”) consists of 3 components: northern area water supply and pipeline project, central city sewage treatment and intercepting sewer project and central city river rehabilitation project. The Project has a construction period of 5 years and a total investment estimate of 825 million yuan, including a World Bank loan of US$60 million yuan. 2. The Project Coordinating and Leading Group of Foreign Funded Projects of Zhaoyang District, Zhaotong Municipality is the executing agency of the Project, and the Management Office of Foreign-funded Urban Construction Projects of Zhaoyang District and the Owner are the implementing agencies of the Project. According to the latest feasibility study outputs, the detailed socioeconomic survey and the impact survey, the Project Management Office (PMO) of Zhaoyang District, Zhaotong Municipality has prepared this RAP with the assistance of the China Cross-Cultural Consulting Center at Sun Yat-sen University (CCCC at SYU) and World Bank experts. B. Impacts of the Project 3. During November 7-15, 2009, the Owner made a detailed survey of the key physical indicators affected by the Project, such as population, houses and attachments, land and special facilities, according to the latest feasibility study outputs, with the assistance of local governments at all levels, administrative villages, communities, villager team officials and the design agency. -

Operation China

Lipo, Western July 4 Location: More than 146,000 past. While the Western Lipo live in an impoverished Eastern Lipo are a area of northern Yunnan Province. Lisu-speaking group They inhabit six counties in Yunnan — who migrated to Dayao, Yongren, Yuanmou, Binchuan, their present Yao’an, and Yongsheng. A small location after a number of Western Lipo spill across military defeat in the border into the Renhe District of 1812,3 the Western Panzhihua County in Sichuan Province. Lipo claim to have originated in Nanjing Identity: There is a great deal of or Jiangxi in eastern confusion regarding the classification China. According to of the Lipo. The Lipo as a whole have local accounts, “the been officially included as part of the ancestors of today’s Yi nationality in China, yet among the Lipuo [Western Lipo are two very distinct groups, Lipo] came as which here are defined as Eastern soldiers at various and Western Lipo. The two do not times from the early consider themselves to be the same Ming to the early people. They have different histories, Qing dynasties [late dress, customs, and languages. This 14th century to late century a further distinction has 17th century]. developed between the two groups: Historical records the Eastern Lipo are known as a confirm that those Christian tribe while the Western Lipo dynasties did send Jamin Pelkey have relatively few Christians. Lipo military expeditions to the area that is Religion: The majority of Western Lipo means “insiders.” They refer to the now Yongren; we can speculate that are polytheists. They worship many Han Chinese as Xipo, or “outsiders.” today’s Lipuo [Western Lipo] are spirits and protective deities, including descendants of intermarriage between mountain deities. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China

Country Report for the Preparation of the First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China June 2003 Beijing CONTENTS Executive Summary Biological diversity is the basis for the existence and development of human society and has aroused the increasing great attention of international society. In June 1992, more than 150 countries including China had jointly signed the "Pact of Biological Diversity". Domestic animal genetic resources are an important component of biological diversity, precious resources formed through long-term evolution, and also the closest and most direct part of relation with human beings. Therefore, in order to realize a sustainable, stable and high-efficient animal production, it is of great significance to meet even higher demand for animal and poultry product varieties and quality by human society, strengthen conservation, and effective, rational and sustainable utilization of animal and poultry genetic resources. The "Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China" (hereinafter referred to as the "Report") was compiled in accordance with the requirements of the "World Status of Animal Genetic Resource " compiled by the FAO. The Ministry of Agriculture" (MOA) has attached great importance to the compilation of the Report, organized nearly 20 experts from administrative, technical extension, research institutes and universities to participate in the compilation team. In 1999, the first meeting of the compilation staff members had been held in the National Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Service, discussed on the compilation outline and division of labor in the Report compilation, and smoothly fulfilled the tasks to each of the compilers. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Environmental Impact Assessment

E1245 v 4 Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank Financed Environment Improvement Project In Panzhihua City, Sichuan Province Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Chengdu Hydropower Investigation Design & Research Institute of China Hydropower Engineering Consultant Group Corporation October, 2005 World Bank Financed Environment Improvement Project in Panzhihua City, Sichuan Province Environmental Impact Assessment Chengdu Hydroelectric Investigation Design & Research Institute of China Hydropower Engineering Consultant Group Corporation Preface Panzhihua City is an important industry base of steel vanadium, titanium and energy in China. Industrial construction is put in the first place while urban construction lags behind relatively in the past. In order to build Panzhihua City into a modernized metropolis, the urban construction process must be accelerated and the urban environment, improved. The environment improvement project which World Bank loan will be used is just to meet the demand of Panzhihua City development. The whole project consists of riverbank slope protection, upper section of Binjiang Road, interceptor and trunk sewers, scenery project and last section of Bingren Road. The four subsections are named as environmental improvement project along the Jinsha River. The gross investment budget of the project is RMB 1220.65 millions Yuan (nearly $ 147.42 millions), and the budget of RMB 577.94 millions Yuan (nearly $ 69.80 millions) will be from the World Bank loan. The construction of the project will improve the urban environment infstructure of Panzhihua City and improve the landscape along the Jinsha River. It can also provide an essential basis for continued urban development and living environment, and lay a solid foundation for turning Panzhihua into a beautiful city. -

Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau

IPP740 REV World Bank-financed Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Ethnic Minority Development Plan of the Yunnan Highway Assets Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau July 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized EMDP of the Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Summary of the EMDP A. Introduction 1. According to the Feasibility Study Report and RF, the Project involves neither land acquisition nor house demolition, and involves temporary land occupation only. This report aims to strengthen the development of ethnic minorities in the project area, and includes mitigation and benefit enhancing measures, and funding sources. The project area involves a number of ethnic minorities, including Yi, Hani and Lisu. B. Socioeconomic profile of ethnic minorities 2. Poverty and income: The Project involves 16 cities/prefectures in Yunnan Province. In 2013, there were 6.61 million poor population in Yunnan Province, which accounting for 17.54% of total population. In 2013, the per capita net income of rural residents in Yunnan Province was 6,141 yuan. 3. Gender Heads of households are usually men, reflecting the superior status of men. Both men and women do farm work, where men usually do more physically demanding farm work, such as fertilization, cultivation, pesticide application, watering, harvesting and transport, while women usually do housework or less physically demanding farm work, such as washing clothes, cooking, taking care of old people and children, feeding livestock, and field management. In Lijiang and Dali, Bai and Naxi women also do physically demanding labor, which is related to ethnic customs. Means of production are usually purchased by men, while daily necessities usually by women. -

Study on Traditional Beliefs and Practices Regarding Maternal and Child Health in Yunnan, Guizhou, Qinghai and Tibet

CDPF Publication No. 8 Study on Traditional Beliefs and Practices regarding Maternal and Child Health in Yunnan, Guizhou, Qinghai and Tibet Research Team of Minzu University of China April 2010 Study on Traditional Beliefs and Practices regarding Maternal and Child Health in Yunnan, Guizhou, Qinghai and Tibet Research Team of Minzu University of China April 2010 Acknowledgments The participants of this research project wish to thank Professor Ding Hong for her critical role guiding this research project from its initiation to completion, and to Associate Professor Guan Kai for his assistance and guidance. This report is a comprehensive summary of five field reports in the targeted areas. The five fields and their respective reporters are: 1. Guizhou province: Yang Zhongdong and Jiang Jianing in Leishan, Ma Pingyan and Shi Yingchuan in Congjiang 2. Yunnan province: Yuan Changgeng, Wu Jie, Lu Xu, Chen Gang and Guan Kai; 3. Qinghai province: Xu Yan, Gong Fang and Ma Liang; and 4. Tibetan Autonomous Region: Min Junqing, Wang Yan and Ma Hong. We wish to acknowledge Yang Zhongdong, Min Junqing, Xu Yan,Yuan Changgeng and Ma Pingyan for preparing the first draft of the comprehensive report, and Yang Zhongdong and Min Junqing for preparing the final report. We thank the following persons in the six targeted areas for their contributions: Guizhou: We thank Professor Shi Kaizhong; Li Yanzhong and Wang Jinhong; Wu Hai, Yang Decheng and Wu Kaihua; MCH Station in Leishan and Congjiang counties and Guizhou University for Nationalities. Yunnan: We appreciate the following friends and colleagues: Chen Xiuqin, Professor Guo Rui, Professor Liu Fang, Dehong Prefecture official Lin Rujian, Yunnan University for Nationalitie, and Yunnan University of Finance and Economics. -

Annual Report 2013 CONTENTS Corporate Information 2

Hidili Industry International Development Limited (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 1393 Annual Report 2013 CONTENTS Corporate Information 2 Chairman’s Statement 4 Management Discussion and Analysis 9 Profile of Directors and Senior Management 19 Directors’ Report 23 Corporate Governance Report 32 Independent Auditor‘s Report 38 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 40 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 42 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 44 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 46 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 49 Financial Summary 128 Hidili Industry International Development Limited 02 CORPORATE INFORMATION DIRECTORS COMPANY SECRETARY EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Ms. Chu Lai Kuen Mr. Xian Yang (Chairman) AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVES Mr. Sun Jiankun Mr. Wang Rong (resigned on 27 August 2013) Mr. Xian Yang Ms. Chu Lai Kuen INDEPENDENT NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS REGISTERED OFFICE Mr. Chan Chi Hing Mr. Chen Limin Cricket Square Mr. Huang Rongsheng Hutchins Drive P.O. Box 2681 AUDIT COMMITTEE Grand Cayman KY1-1111 Mr. Chan Chi Hing (Chairman) Cayman Islands Mr. Chen Limin Mr. Huang Rongsheng HEAD OFFICE REMUNERATION COMMITTEE 16th Floor, Dingli Mansion No. 185 Renmin Road Mr. Chan Chi Hing (Chairman) Panzhihua Mr. Chen Limin Sichuan 617000 Mr. Huang Rongsheng PRC Mr. Xian Yang PRINCIPAL PLACE OF BUSINESS AUDITORS IN HONG KONG Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Unit 3702, 37th Floor Certified public accountants West Tower, Shun Tak Centre 35th Floor, One Pacific Place 168–200 Connaught Road 88 Queensway Central Hong Kong Hong Kong Annual Report 2013 Hidili Industry International Development Limited CORPORATE INFORMATION 03 PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR AND WEBSITE TRANSFER OFFICE http://www.hidili.com.cn Royal Bank of Canada Trust Company (Cayman) Limited 4th Floor, Royal Bank House PRINCIPAL BANKERS 24 Shedden Road, George Town Grand Cayman KY1-1110 China Minsheng Banking Corp. -

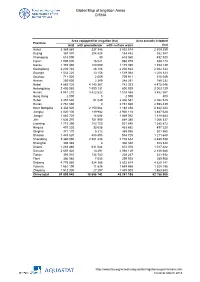

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52