TITLE Implementation of the State Children's Health Insurance Program: Synthesis of State Evaluations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bioarchaeological Perspective Michael Pietrusewskya, Michele Toomay Douglasa, Marilyn K

This article was downloaded by: [Professor Michael Pietrusewsky] On: 07 November 2014, At: 13:30 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uica20 Health in Ancient Mariana Islanders: A Bioarchaeological Perspective Michael Pietrusewskya, Michele Toomay Douglasa, Marilyn K. Swiftb, Randy A. Harperb & Michael A. Flemingb a Department of Anthropology, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, USA b Swift and Harper Archaeological Resource Consulting, Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands, USA Published online: 06 Nov 2014. To cite this article: Michael Pietrusewsky, Michele Toomay Douglas, Marilyn K. Swift, Randy A. Harper & Michael A. Fleming (2014) Health in Ancient Mariana Islanders: A Bioarchaeological Perspective, The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 9:3, 319-340, DOI: 10.1080/15564894.2013.848959 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2013.848959 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. -

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

Guam 179: Facing Te New,Pacific Era

, DOCONBOT Busehis BD 103 349 RC 011 911 TITLE Guam 179: Facing te New,Pacific Era. AnnualEconom c. Review. INSTITUTION .Guam Dept. of Commerce, Agana. SPONS AGENCY Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Aug 79 . NOTE 167p.: Docugent prepared by the Economic,Research Center. EDRS ?RICE . 1F01/PC07Plus 'Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annual Reports: Business: *Demography: *Economic Dpveloptlent4 Employment Patternp:Expenditures: Federal GoVernment: Financial, Support: *Government Role:_Local Government: *Productivity;_ Vahles (Data); Tourism - IDENTIFIER, *Guam Micronesia A ABSTRACT Socioeconomic conditions and developmentSare analysed.in thiseport, designed to ge. useful\ tb plannersin government and t_vr,. rivate sector. The introduction sunrmarizes Guam's economic olthook emphasizing the eftect of federalfunds for reconstruction folloVing SupertirphAon.Pamela in 1976,moderate growth ,in tour.ism,,and Guam's pqtential to partici:pateas a staging point in trade between the United States and mainlandQhina The body of the report contains populaktion, employment, and incomestatistics; an -account of th(ik economic role of local and federalgovernments and the military:adescription of economic activity in the privatesector (i.e., tour.isid, construction, manufacturingand trarde, agziculture and .fisheries and finan,cial inStitutionsi:and a discussion of onomic development in. Micronesia 'titsa whole.. Appendices contain them' 1979 uGuam Statistical Abstract which "Constitutesthe bulk Of tpe report and provides a wide lia.riety of data relevantto econ9mic development and planning.. Specific topics includedemography, vital statistics, school enrollment, local and federalgovernment finance, public utilities, transportation, tourism, andinternational trade. The most current"data are for fiscalyear 1977 or 197B with many tables showing figures for the previous 10years.(J11) A , . ***************t*********************************************t********* * . -

Freshwater Use Customs on Guam an Exploratory Study

8 2 8 G U 7 9 L.I:-\'I\RY INT.,NATIONAL R[ FOR CO^.: ^,TY W SAMIATJON (IRC) FRESHWATER USE CUSTOMS ON GUAM AN EXPLORATORY STUDY Technical Report No. 8 iei- (;J/O; 8;4J ii ext 141/142 LO: FRESHWATER USE CUSTOMS ON AN EXPLORATORY STUDY Rebecca A. Stephenson, Editor UNIVERSITY OF GUAM Water Resources Research Center Technical Report No. 8 April 1979 Partial Project Completion Report for SOCIOCULTURAL DETERMINANTS OF FRESHWATER USES IN GUAM OWRT Project No. A-009-Guam, Grant Agreement Nos. 14-34-0001-8012,9012 Principal Investigator: Rebecca A- Stephenson Project Period: October 1, 1977 to September 30, 1979 The work upon which this publication is based was supported in part by funds provided by the Office of Water Research and Technology, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C, as authorized by the Water Research and Development Act of 1978. T Contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Office of Water Research and Technology, U. S. Department of the Interior, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute their endorsement or recommendation for use by the U- S. Government. ii ABSTRACT Traditional Chamorro freshwater use customs on Guam still exist, at least in the recollections of Chamorros above the age of 40, if not in actual practice in the present day. Such customs were analyzed in both their past and present contexts, and are documented to provide possible insights into more effective systems of acquiring and maintain- ing a sufficient supply of freshwater on Guam. -

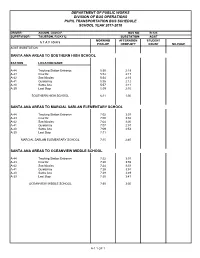

Department of Public Works Division of Bus Operations Pupil Transportation Bus Schedule School Year 2017-2018

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. BUS NO. B-123 SUPERVISOR: TAIJERON, RICKY U. SUBSTATION: AGAT MORNING AFTERNOON STUDENT S T A T I O N S PICK-UP DROP-OFF COUNT MILEAGE AGAT SUBSTATION SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL STATION LOCATION NAME A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 SANTA ANA AREAS TO MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:02 3:03 A-43 Cruz #2 7:00 3:02 A-42 San Nicolas 7:04 3:00 A-41 Quidachay 7:07 2:57 A-40 Santa Ana 7:09 2:53 A-39 Last Stop 7:11 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:15 2:40 SANTA ANA AREAS TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:22 3:57 A-43 Cruz #2 7:20 3:55 A-42 San Nicolas 7:24 3:53 A-41 Quidachay 7:26 3:51 A-40 Santa Ana 7:28 3:49 A-39 Last Stop 7:30 3:47 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:30 A-1 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: BORJA, GARY P. -

UNIVERSITY of HAWAII LIBRARY

UNIVERSITY Of HAWA II LI BRARY 0 RECORDS OF 'IllE GERMAN IMPEHIAL GOVEHNMENT • OF THE SOUTII SEAS PER'D\INING TO MICRONESIA J\S CON'D\ INED IN 'fl-IE A,rtC.:llIVES Ol"F'ICE , AUSTRALIJ\N NATION/\L GOVlmNMENT CANBERHA Volume 8 CRS Gl, ITEM 9-2 General Administration, Caroline Islands 1899 - 1907 Property of l>i.vislon of Lancls ancl Surveys UcparlmcnL of Resources and Dcvclopmcnl Trust Territo ry Government Snipan, Mariana Islands 96950 CRS G1 ITEM 9-~ ALLGE~EINE VER ~ ALTUNG KAROLINEN 1899-1907 ( GEi~3!L.L .rt ~l ..Ii:IL7H.i.T I Oli CA.HOLIHE ISLAirnS) RECORDS OF nrn GERMAN IMPERIAL GOVERNMENT. OF THE SOUTii SFAS PER'D\INING TO MICRONESIA AS CONTAINED IN nrn ARCHIVES OFFICE , AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL GOVERNMENT CANBERRA Volume 8 CRS Gl , ITEM 9-2 General Administration, Caroline Islands 1899 - 1907 Property of Division of Lands and Surveys Department of Resources and Development Trust Territory Government Saipan, Mariana Islands 96950 INTRODUCTION The two main sources for land records and documents relating t~ the Administration of Micronesia by Germany (Marshalls 1885-1914; Carolines and Marianas 1899-1914) are the Commonwealth of Australia Archives Office in Canberra and the Central German Archives at Potsdam.in East Germany • • The German records in Australia were acquired by the Australian Military Administration of New Guinea between 1914 and 1922 from Rabaul, the ' former German capital of German New Guinea and the Islands Sphere (Micronesia). These records are voluminous, and James B. Johnson, Senior Land Commissioner, Mariana Islands District, was sent to Canberra for ten (10) days in August 1969 to examine these records. -

Implementation of the State Children's Health Insurance Program

Contract No.: 500-96-0016(03) MPR Reference No.: 8644-100 Implementation of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program: Synthesis of State Evaluations Background for the Report to Congress March 2003 Margo Rosenbach Marilyn Ellwood Carol Irvin Cheryl Young Wendy Conroy Brian Quinn Megan Kell Submitted to: Submitted by: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. Office of Research, Development, 50 Church Street, 4th Floor and Information Cambridge, MA 02138 7500 Security Boulevard (617) 491-7900 Baltimore, MD 21244 Project Officer: Project Director: Rosemarie Hakim Margo Rosenbach This report was prepared for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under CMS contract number 500-96-0016 (03). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CMS or DHHS, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by CMS, DHHS, or Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of this publication. CONTENTS Chapter Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................. xiii I INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................1 A. OVERVIEW OF SCHIP AS OF MARCH 31, 2001 ....................................1 B. RATIONALE FOR THIS REPORT .............................................................7 C. ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT ........................................................9 -

Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-1

APPENDIX D NHPA Section 106 Consultation Supporting Documentation Section 106 Consultation Request Letter February 1, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-1 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-2 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-3 Conceptual Project Plans for Section 106 Consultation, February 28, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-4 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-5 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-6 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-7 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-8 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-9 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-10 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-11 Request for HPO and NPS Review of Draft Phase I Cultural Resources Report April 16, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-12 Request for Review of Phase I Cultural Resources Survey, May 25, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-13 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-14 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-15 Section 106 Review and Comments Letter from CNMI HPO May 31, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-16 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-17 Response to Request for Review of Phase I Cultural Resources Survey Letter, June 25, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-18 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-19 USAF News Release regarding historical sites at GSN and TNI September 2, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-20 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-21 Section 106 Consultation Initiation Letter September 11, 2012 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-22 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-23 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-24 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-25 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-26 Revised Draft Divert EIS Appendix D D-27 Note: Culturally sensitive information has been redacted from this page. -

Jose D. Leon Guerrero Commercial Port of Guam Master Plan Update 2007

Jose D. Leon Guerrero Commercial Port of Guam Master Plan Update 2007 Report to the Legislature Pursuant to 5 GCA Chapter 9 § 9301 Prepared for The Port Authority of Guam Revised August 3, 2009 Performed by PB International, Inc. In Association with BST Associates Jose D. Leon Guerrero Commercial Port of Guam Master Plan Update 2007 Report to the Legislature Pursuant to 5 GCA Chapter 9 § 9301 Prepared for The Port Authority of Guam Revised August 3, 2009 This study report was prepared under contract with the Port Authority of Guam, Government of Guam on behalf of the United States Territory of Guam Performed by PB International, Inc. In Association with BST Associates Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Implementation Plan .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Financial Plan ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 Economic Impact Statement ................................................................................................................................ 10 Section 1 Introduction & -

2021 Guam Highway Safety Plan

THE TERRITORY OF GUAM’S 2021 HIGHWAY SAFETY PLAN 1 | Page Contents Highway Safety Plan ........................................................................................................................... 10 Highway safety planning process....................................................................................................... 11 Data Sources and Processes ............................................................................................................... 12 Processes Participants ........................................................................................................................ 13 Description of Highway Safety Problems ......................................................................................... 14 Methods for Project Selection ............................................................................................................ 16 List of Information and Data Sources ............................................................................................... 16 Description of Outcomes .................................................................................................................... 17 Performance report ............................................................................................................................ 18 Performance Measure: C-1) Number of traffic fatalities (Territory crash data files) ............. 19 Program-Area-Level Report ..................................................................................................... -

Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement Guam and CNMI

Guam and CNMI Military Relocation (2012 Roadmap Adjustments) SEIS Final July 2015 CHAPTER 3 RESOURCE DEFINITIONS AND APPROACH TO ANALYSIS This chapter lays the foundation for understanding each of the 18 environmental resources that were analyzed for this SEIS and summarizes the approach taken to evaluate potential impacts to each resource. These same resources were also analyzed in the 2010 Final EIS and much of the summary information presented in this chapter incorporates by reference the more detailed resource descriptions in the 2010 Final EIS. As applicable, this chapter highlights any changes in resource characteristics, regulations, or analytical approach that has occurred since publication of the 2010 Final EIS. Each resource is discussed in terms of a definition, the regulatory framework, and the approach to analysis used this SEIS. Each resource definition summarizes key components and characteristics that are explored as appropriate in the environmental consequences sections later in this SEIS (Chapters 4, 5, 6, and 7). The regulatory framework describes the relevant laws and government regulations that pertain to each resource, particularly with regard to identifying impacts to the resource and determining thresholds for significance of those impacts. The approach to analysis describes in general terms the methodology and impact assessment criteria used to identify and categorize resource impacts in this SEIS, and review the key concerns and issues raised about each resource during the two public scoping periods. 3.1 GEOLOGICAL AND SOIL RESOURCES 3.1.1 Definition The comprehensive description of the geological and soil resources of Guam in this SEIS is the same as that provided in the 2010 Final EIS (Volume 2, Chapter 3: Geological and Soil Resources, Section 3.1: Affected Environment, pages 3‐1 to 3-30). -

Highway Safety Plan FY 2020 Guam

September 2019 Highway Safety Plan FY 2020 Guam Highway Safety Plan NATIONAL PRIORITY SAFETY PROGRAM INCENTIVE GRANTS - The State applied for the following incentive grants: S. 405(b) Occupant Protection: Yes S. 405(e) Distracted Driving: No S. 405(c) State Traffic Safety Information System Improvements: Yes S. 405(f) Motorcyclist Safety Grants: No S. 405(d) Impaired Driving Countermeasures: No S. 405(g) State Graduated Driver Licensing Incentive: No S. 405(d) Alcohol-Ignition Interlock Law: No S. 405(h) Nonmotorized Safety: No S. 405(d) 24-7 Sobriety Programs: No S. 1906 Racial Profiling Data Collection: No Highway safety planning process Data Sources and Processes 2020 PLANNING CALENDAR Months Activities 1/144 January to March Review progress and prior year programs with DPW Office of Highway Safety staffs as well as analyze data to identify upcoming fiscal year key program areas. Review spending and determine revenue estimates. Grant application process begins for FY 2020. Obtain in-put from partner entities and stakeholders on program direction.Review progress and prior year programs with DPW Office of Highway Safety staffs as well as analyze data to identify upcoming fiscal year key program areas. Review spending and determine revenue estimates. Grant application process begins for FY 2020. Obtain in-put from partner entities and stakeholders on program direction.Review progress and prior year programs with DPW Office of Highway Safety staffs as well as analyze data to identify upcoming fiscal year key program areas. Review spending and determine revenue estimates. Grant application process begins for FY 2020. Obtain in-put from partner entities and stakeholders on program direction.Review progress and prior year programs with DPW Office of Highway Safety staffs as well as analyze data to identify upcoming fiscal year key program areas.