Single Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Takeshi Inomata Address Positions

Inomata, Takeshi - page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Takeshi Inomata Address School of Anthropology, University of Arizona 1009 E. South Campus Drive, Tucson, AZ 85721-0030 Phone: (520) 621-2961 Fax: (520) 621-2088 E-mail: [email protected] Positions Professor in Anthropology University of Arizona (2009-) Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in Environment and Social Justice University of Arizona (2014-2019) (Selected as one of the four chairs university-wide, that were created with a major donation). Associate Professor in Anthropology University of Arizona (2002-2009) Assistant Professor in Anthropology University of Arizona (2000-2002) Assistant Professor in Anthropology Yale University (1995-2000) Education Ph.D. Anthropology, Vanderbilt University (1995). Dissertation: Archaeological Investigations at the Fortified Center of Aguateca, El Petén, Guatemala: Implications for the Study of the Classic Maya Collapse. M.A. Cultural Anthropology, University of Tokyo (1988). Thesis: Spatial Analysis of Late Classic Maya Society: A Case Study of La Entrada, Honduras. B.A. Archaeology, University of Tokyo (1986). Thesis: Prehispanic Settlement Patterns in the La Entrada region, Departments of Copán and Santa Bárbara, Honduras (in Japanese). Major Fields of Interest Archaeology of Mesoamerica (particularly Maya) Politics and ideology, human-environment interaction, household archaeology, architectural analysis, performance, settlement and landscape, subsistence, warfare, social effects of climate change, LiDAR and remote sensing, ceramic studies, radiocarbon dating, and Bayesian analysis. Inomata, Takeshi - page 2 Extramural Grants - National Science Foundation, research grant, “Preceramic to Preclassic Transition in the Maya Lowlands: 1100 BC Burials from Ceibal, Guatemala,” (Takeshi Inomata, PI; Daniela Triadan, Co-PI, BCS-1950988) $298,098 (2020/6/3-8/31/2024). -

COMPENDIO DE LEYES SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL GUATEMALTECO Título: COMPENDIO DE LEYES SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL GUATEMALTECO

COMPENDIO DE LEYES SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL GUATEMALTECO Título: COMPENDIO DE LEYES SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL GUATEMALTECO Katherine Grigsby Representante y Directora de UNESCO en Guatemala Blanca Niño Norton Coordinadora Proyecto PROMUSEUM Oscar Mora, Consultor, Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes © UNESCO, 2006 ISBN: 92-9136-082-1 La Información contenida en esta publicación puede ser utilizada siempre que se cite la fuente. COMPENDIO DE LEYES SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL DE GUATEMALA CULTURAL DEL PATRIMONIO COMPENDIO DE LEYES SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN ÍNDICE Constitución Política de la República de Guatemala 7 Ley para la Protección del Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación 9 Ley Protectora de la Ciudad de la Antigua Guatemala 25 Código Penal 35 Reglamento de Funcionamiento del Parque Nacional Tikal 39 Acuerdo Ministerial sobre Protección de Kaminal Juyú 43 Acuerdo Ministerial sobre las Normas para la Protección y uso de las Áreas Adyacentes afectas al Montículo de la Culebra y Acueducto de Pinula 45 Acuerdo de Creación de Zonas y Monumentos Arqueológicos Históricos y Artísticos de los Periodos Prehispánico e Hispánico 47 Acuerdo Ministerial Número 721-2003 56 Reglamento para la Protección y Conservación del Centro Histórico y los Conjuntos Históricos de la Ciudad de Guatemala 61 Convención para la Protección del Patrimonio Mundial, Cultural y Natural 69 Convención sobre las Medidas que deben adoptarse para Prohibir e Impedir la Importación, la Exportación y la Transferencia de Propiedad Ilícita -

Site Q: the Case for a Classic Maya Super-Polity

Site Q: The Case for a Classic Maya Super-Polity Simon Martin 1993 As the historical record left to us by the Classic Maya is slowly pieced together from various epigraphic clues, a single political entity, the state Peter Mathews has dubbed "Site Q", shows an ever greater presence. Over the last few years, and certainly since Mathews' original manuscript discussing Site Q (1979), a great deal of new data has emerged. These come not only from new finds provided by archaeological investigations, but more general advances in epigraphic research that have allowed us to reassess well-known texts, giving a fuller picture of Site Q's place in the political geography of the Classic Period. The original Mayan name of the Site Q polity, expressed in its Emblem Glyph, was Kan "snake". Glyphically, it is usually preceded by the phonetic complement ka and often followed by the nominal ending -al to give K'ul Kanal Ahaw as a full reading for the compound (the suffix is not apparent in all examples and it is not clear whether this is an optional feature or was always read by context). In this, it joins Piedras Negras (Yokib), Yaxha (Yaxha), Palenque (Bak), Caracol (K'an-tu-mak), Pomona (Pakab) and Ucanal (K'an Witz Nal) in having a readable ancient name. It is tempting to use Kan or Kanal instead of 'Site Q', since it avoids the difficulty of assigning this Emblem to any single site and will be equally relevant when Site Q is identified and the term becomes redundant, but for this present study I will stick with the Mathews moniker. -

30 Explorations at the Site of Nacimiento, Petexbatún, Petén

30 EXPLORATIONS AT THE SITE OF NACIMIENTO, PETEXBATÚN, PETÉN Markus Eberl Claudia Vela Keywords: Maya archaeology, Guatemala, Petén, Petexbatún, Nacimiento, minor architecture In the 2004 season the archaeological excavations at the site of Nacimiento, in the Petexbatún region, continued. The site of Nacimento, or more precisely, Nacimiento de Aguateca, to make a proper distinction with other sites and towns with the same name, is located approximately 2.5 km south of the site of Aguateca (Figure 1). The hieroglyphic inscriptions of Aguateca and other neighbor sites like Dos Pilas, narrate the history of the Petexbatún region during the Classic period. One crucial event was the entering of the Dos Pilas dynasty in the region in the VII century AD. The Dos Pilas dynasty substituted the dynasty of Tamarindito and Arroyo de Piedra as a regional power. In which way did this political change affect the population of the Petexbatún region? This is the question that guided archaeological investigations conducted at the minor site of Nacimiento, occupied before and after the arrival of the Dos Pilas dynasty. Extensive excavations conducted at residential groups in Nacimiento have made it possible to analyze the effect that this political shift exerted on local inhabitants. Figure 1. Map of the Petexbatún region (by M. Eberl). 1 During 2003 a structure was excavated, nearby presumed agricultural terraces. This season work continued with the extensive excavation of two structures from two residential groups located at the core of Nacimiento. THEORETICAL FRAME The investigation at Nacimiento was carried out as part of the Aguateca Archaeological Project, whose second phase, under the direction of Daniela Triadan, was initiated on June of 2004. -

Aproximación a La Conservación Arqueológica En Guatemala: La Historia De Un Dilema

86. AP RO X IMACIÓN A LA CON S ERVACIÓN a r qu e o l ó g i c a e n gU a t e m a l a : LA HI S TORIA DE U N DILEMA Erick M. Ponciano XXVIII SIMPO S IO DE IN V E S TIGACIONE S AR QUEOLÓGICA S EN GUATEMALA MU S EO NACIONAL DE AR QUEOLOGÍA Y ETNOLOGÍA 14 AL 18 DE JULIO DE 2014 EDITOR E S Bá r B a r a ar r o y o LUI S MÉNDEZ SALINA S LO R ENA PAIZ REFE R ENCIA : Ponciano, Erick M. 2015 Aproximación a la conservación arqueológica en Guatemala: la historia de un dilema. En XXVIII Simpo- sio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2014 (editado por B. Arroyo, L. Méndez Salinas y L. Paiz), pp. 1053-1064. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. APROXIM A CIÓN A L A CONSERV A CIÓN A RQUEOLÓGIC A EN GU A TEM A L A : L A HISTORI A DE UN DILEM A Erick M. Ponciano PALABRAS CLAVE Guatemala, recursos culturales, conservación, época prehispánica. ABSTRACT Guatemala has many archaeological sites from pre-colombian times. This characteristic creates a paradoji- cal and complex situation to Guatemala as a society. On one side, there exists a feeling of proud when sites like Tikal, Mirador or Yaxha are mentioned, but on the other side, also exits uncertainty on private lands due to the fear for expropriation from the State when archaeological sites occur in their terrain. Different forms for cultural preservation are presented and how this has developed through time in Guatemala. -

Historia De Los Ejercitos (Rustica) Grande.Indd 1 07/01/14 15:00 Presidencia De La República

historia de los ejercitos (rustica) grande.indd 1 07/01/14 15:00 PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA Presidente de la República Enrique Peña Nieto SECRETARÍA DE LA DEFENSA NACIONAL Secretario de la Defensa Nacional General Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda SECRETARÍA DE EDUCACIÓN PÚBLICA Secretario de Educación Pública Emilio Chuayffet Chemor Subsecretario de Educación Superior Fernando Serrano Migallón INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS HISTÓRICOS DE LAS REVOLUCIONES DE MÉXICO Directora General Patricia Galeana Consejo Técnico Consultivo Fernando Castañeda Sabido, Mercedes de la Vega, Luis Jáuregui, Álvaro Matute, Ricardo Pozas Horcasitas, Érika Pani, Salvador Rueda Smithers, Adalberto Santana Hernández, Enrique Semo y Gloria Villegas Moreno. historia de los ejercitos (rustica) grande.indd 2 07/01/14 15:00 INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS HISTÓRICOS DE LAS REVOLUCIONES DE MÉXICO México, 2013 historia de los ejercitos (rustica) grande.indd 3 07/01/14 15:00 El INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS HISTÓRICOS DE LAS REVOLUCIONES DE MÉXICO desea hacer constar su agradecimiento a quienes hicieron posible, a través del uso y permiso de imágenes, esta publicación: • Archivo Bob Schalkwijk • Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo • Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) • Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA) • Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional (Sedena) Primera edición, 2014 ISBN: 978-607-9276-41-6 Imagen de portada: Insignia militar, s. XIX, Museo Nacional de Historia-INAH Derechos reservados de esta edición: © Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM) Francisco I. Madero núm. 1, San Ángel, Del. Álvaro Obregón, 01000, México, D. F. www.inehrm.gob.mx Impreso y hecho en México historia de los ejercitos (rustica) grande.indd 4 07/01/14 15:00 CONTENIDO P RESENTACIONES General Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda Secretario de la Defensa Nacional .........................................9 Emilio Chuayffet Chemor Secretario de Educación Pública ........................................ -

Zooarchaeological Habitat Analysis of Ancient Maya Landscape Changes

Journal of Ethnobiology 28(2): 154–178 Fall/Winter 2008 ZOOARCHAEOLOGICAL HABITAT ANALYSIS OF ANCIENT MAYA LANDSCAPE CHANGES KITTY F. EMERYa and ERIN KENNEDY THORNTONb a Environmental Archaeology, Florida Museum of Natural History, Dickinson Hall, Museum Road, 117800 University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-7800 ^[email protected]& b Department of Anthropology, 117305 University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-7305 ^[email protected]& ABSTRACT.—Consensus has not yet been reached regarding the role of human- caused environmental change in the history of Classic Maya civilization. On one side of the debate, researchers argue that growing populations and agricultural expansion resulted in environmental over-exploitation that contributedto societal collapse. Researchers on the other side of the debate propose more gradual environmental change resulting from intentional and sustainable landscape management practices. In this study, we use zooarchaeological data from 23 archaeological sites in 11 inland drainage systems to evaluate the hypothesis of reduction of forest cover due to anthropogenic activities across the temporal and spatial span of the ancient Maya world. Habitat fidelity statistics derived from zooarchaeological data are presented as a proxy for the abundance of various habitat types across the landscape. The results of this analysis do not support a model of extensive land clearance and instead suggest considerable chronological and regional stability in the presence of animals from both mature and secondary forest habitats. Despite relative stability, some chronological variation in land cover was observed, but the variation does not fit expected patterns of increased forest disturbance during periods of greatest population expansion. These findings indicate a complex relationship between the ancient Maya and the forested landscape. -

El Vaso De Altar De Sacrificios: Un Estudio Microhistórico Sobre Su Contexto Político Y Cosmológico

48. EL VASO DE ALTAR DE SACRIFICIOS: un estudio Microhistórico sobre su contexto Político y cosMológico Daniel Moreno Zaragoza XXIX SIMPOSIO DE INVESTIGACIONES ARQUEOLÓGICAS EN GUATEMALA MUSEO NACIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA Y ETNOLOGÍA 20 AL 24 DE JULIO DE 2015 EDITORES BárBara arroyo LUIS MÉNDEZ SALINAS Gloria ajú álvarez REFERENCIA: Moreno Zaragoza, Daniel 2016 El Vaso de Altar de Sacrificios: un estudio microhistórico sobre su contexto político y cosmológico. En XXIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2015 (editado por B. Arroyo, L. Méndez Salinas y G. Ajú Álvarez), pp. 605-614. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. EL VASO DE ALTAR DE SACRIFICIOS: UN ESTUDIO MICROHISTÓRICO SOBRE SU CONTEXTO POLÍTICO Y COSMOLÓGICO Daniel Moreno Zaragoza PALABRAS CLAVE Petén, Altar de Sacrificios, Motul de San José, wahyis, coesencias, cerámica Ik’, Clásico Tardío. ABSTRACT In 1962 Richard Adams discovered at Altar de Sacrificios a ceramic vessel that would become transcendent for our understanding of the animic conceptions among the ancient Maya. Such vase (K3120), now at the Museo Nacional de Arquoelogía y Etnología, has become an emblematic piece for Guatemalan archaeo- logy. The history of such vessel will be reviewed in this paper, from its production to its ritual deposition. The iconographic motifs will be analyzed as well as the epigraphic texts. A microhistoric study is inten- ded to know some aspects of the regional political situation (represented through the so called “emblem glyphs”), as well as the Maya conceptions about animic entities. The study of the context of production of the piece, its intention, mobility and the represented themes in it can reveal us deep aspects of Maya cosmology and politics during the Late Classic. -

A Variant of the Chak Sign B

10 A Variant of the chak Sign DAVID STUART Princeton University HE PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT is to present brief arguments leading to the recognition Tof a new variant of Tl09, commonly agreed to have the value chak, "red," or, sometimes, "great" (Justeson 1984:324). The variant sign is that of an inverted mandible, a repre sentation not to be confused with Tl11, the depiction of a simple longbone whose special markings relate it graphically to Tl09. The first context where the jawbone variant of chak becomes clear is the name glyph of "Jaguar Paw Skull" (Fig. 1a,b), associated with the early inscriptions of Tikal (Jones & Satterthwaite 1982:127). This name may be the same as that of an even earlier Tikal ruler known as "Jaguar Paw" (Fig. 1c), since the only difference between the two hieroglyphic names lies in the presence or absence of the skull which, when present, has the jaguar paw on its nose. A name on Tikal Stela 39 (dated at 8.17.0.0.0) shows that the "Jaguar Paw Skull" hieroglyph can be used as the name of the earlier "Jaguar Paw," effectively obliterating any distinction between the two name designations (Fig. 1d). Another example of the name (Fig. Ie) appears in the headdress depicted on an Early Classic cache vessel of unknown provenance (Berjonneau, Deletaille, & Sonnery 1985:231). While the names of these kings appear to be identical, it is clear that we are dealing with two persons rather than one. a g b d c a: TIK Stela 26, left side, zB4 (After drawing by William R. -

Amenaza Por Deslizamientos E Inundaciones

AMENAZA CODIGO: AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS E INUNDACIONES POR DESLIZAMIENTOS DEPARTAMENTO DE PETEN La pre d ic c ión d e e sta am e naza utiliza la m e tod ología re c onoc id a 1712 d e Mora-V ahrson, para e stim ar las am e nazas d e d e slizam ie ntos a un nive l d e d e talle d e 1 kilóm e tro. Esta c om ple ja m od e lac ión utiliza una c om binac ión d e d atos sobre la litología, la hum e d ad d e l sue lo, MUNICIPIO DE POPTÚN pe nd ie nte y pronóstic os d e tie m po e n e ste c aso pre c ipitac ión 550000.000000 560000.000000 570000.000000 580000.000000 590000^.000000 600000.000000 610000.000000 620000.000000 630000.000000 640000.000000 650000.000000 90°0'W 89°50'W 89°40'W " 89°30'W 89°20'W 89°10'W ac um ulad a q ue CATHALAC ge ne ra d iariam e nte a través d e l " " m od e lo m e sosc ale PSU/N CAR, e l MM5. Finca El Rosario El Pacay Pantano " " Sitio é Finca La San Valentin "San Juan t Laguneta La Finca La R ic "Moquena Las Flores Parcelamiento Arqueologico Río L" a Fí uenten Se e stim a e sta am e naza e n térm inos d e ‘Baja’, ‘Me d ia’ y ‘Alta‘. "Colorada "Chapala Finca El " Colpeten o Sa San Morena R Colorada " R " " Quibix El Pumpal El Chal La P" uente " " " Dolores "Camayal Finca La "Marcos Laguneta " Finca Las Estrella "Sanicte Santo " "El Campo E B e lE i c e Joyas La Colorada Finca " Toribio " Finca " " Finca Luz Del Campuc R " " í Río Chiquibul Rancho Brasilia Cristo Rey Valle o Finca Valle " S V Grande V Alta " Finca a De Las Finca c Mopan A Sabaneta u Manuel " Esmeraldas Z l " La Paz " A Tres L Comunidad L " " N -

Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information

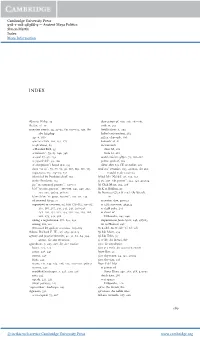

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48388-9 — Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information INDEX Abrams, Philip, 39 destruction of, 200, 258, 282–283 Acalan, 16–17 exile at, 235 accession events, 24, 32–33, 60, 109–115, 140, See fortifications at, 203 also kingship halted construction, 282 age at, 106 influx of people, 330 ajaw as a verb, 110, 252, 275 kaloomte’ at, 81 as ajk’uhuun, 89 monuments as Banded Bird, 95 Altar M, 282 as kaloomte’, 79, 83, 140, 348 Stela 12, 282 as sajal, 87, 98, 259 mutul emblem glyph, 73, 161–162 as yajawk’ahk’, 93, 100 patron gods of, 162 at a hegemon’s home seat, 253 silent after 810 CE or earlier, 281 chum “to sit”, 79, 87, 89, 99, 106, 109, 111, 113 Ahk’utu’ ceramics, 293, 422n22, See also depictions, 113, 114–115, 132 mould-made ceramics identified by Proskouriakoff, 103 Ahkal Mo’ Nahb I, 96, 130, 132 in the Preclassic, 113 aj atz’aam “salt person”, 342, 343, 425n24 joy “to surround, process”, 110–111 Aj Chak Maax, 205, 206 k’al “to raise, present”, 110–111, 243, 249, 252, Aj K’ax Bahlam, 95 252, 273, 406n4, 418n22 Aj Numsaaj Chan K’inich (Aj Wosal), k’am/ch’am “to grasp, receive”, 110–111, 124 171 of ancestral kings, 77 accession date, 408n23 supervised or overseen, 95, 100, 113–115, 113–115, as 35th successor, 404n24 163, 188, 237, 239, 241, 243, 245–246, as child ruler, 245 248–250, 252, 252, 254, 256–259, 263, 266, as client of 268, 273, 352, 388 Dzibanche, 245–246 taking a regnal name, 111, 193, 252 impersonates Juun Ajaw, 246, 417n15 timing, 112, 112 tie to Holmul, 248 witnessed by gods or ancestors, 163–164 Aj Saakil, See K’ahk’ Ti’ Ch’ich’ Adams, Richard E. -

LAS OFRENDAS DE COTZUMALGUAPA, GUATEMALA, EN EL CLÁSICO TARDÍO (650/700-1000 D.C.) ERIKA MAGALI GÓMEZ GONZÁLEZ

Instituto Politécnico de Tomar – Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (Departamento de Geologia da UTAD – Departamento de Território, Arqueologia e Património do IPT) Master Erasmus Mundus em QUATERNARIO E PRÉ-HISTÓRIA Dissertação final: LAS OFRENDAS DE COTZUMALGUAPA, GUATEMALA, EN EL CLÁSICO TARDÍO (650/700-1000 d.C.) ERIKA MAGALI GÓMEZ GONZÁLEZ Orientador: Prof. Davide Delfino Co-Orientador: Dr. Oswaldo Chinchilla Júri: Ano académico 2010/2011 RESUMEN Se estudió un conjunto de artefactos que conforman las ofrendas de las estructuras y espacios de patios, de un conjunto arquitectónico descubierto en las inmediaciones del sitio El Baúl, localizado en la Zona arqueológica de Cotzumalguapa, departamento de Escuintla, Guatemala. Las 21 ofrendas tratadas, constituyen el primer hallazgo relativamente masivo de este tipo, localizado en esta zona, gracias a las excavaciones realizadas por el Proyecto Arqueológico Cotzumalguapa durante los años 2002, 2006 y 2007. Aquellas son manifestaciones de los comportamientos rituales de una parte de la sociedad costeña del sur, durante el periodo Clásico Tardío (650/700-1000 d.C.). Estos objetos habían sido tratados en forma breve en un artículo reciente (Méndez y Chinchilla s.f.). Sin embargo, la presente investigación se concentró en ciertos aspectos del propio contexto y en su comparación con los de otras áreas, para tratar de entender la intencionalidad de los depósitos. Existe variedad en los artefactos componentes de cada ofrenda. Se trata entonces de objetos de cerámica, en su mayoría vasijas, de servicio y en menor cantidad hay formas utilitarias, además de una figurilla. También hay objetos de obsidiana, exceptuando un núcleo prismático todos los demás son navajas prismáticas.