Polygons and Practice in Skies of Arcadia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview Responses from Queer Tomb Raider Fans

Interview responses from queer Tomb Raider fans Template response form sent to consenting parties: Your name or chosen alias (Anonymous is fine too): Country: Age: How you identify: --- 1) How and when did you come to the fandom? (ie. how long have you been a fan?) 2) Why Lara Croft? What do you like/admire about her? What do you think drew you to her? 3) Can you describe Lara Croft's impact on your sexuality? (If not and/or you don't feel she's been an influence, that's fine too). 4) Do you have a Lara preference - Classic or Reboot? Name: Joshua B. Country: USA Age: 22 How you identify: Cisgender gay man --- 1) How and when did you come to the fandom? (ie. how long have you been a fan?) I've only been a fan for about a year! I got into the series in 2014 with Tomb Raider (2013). I later branched out and explored the classic series by Core Design and disliked them, but I was only really inspired/convinced to return to the Core games when my ex-boyfriend brought up a new viewpoint: people play Tomb Raider for puzzles, not for plot. And so I went back and I was hooked! A year later, here I am as a Tomb Raider fanatic. 2) Why Lara Croft? What do you like/admire about her? What do you think drew you to her? I really admired how 2013 Lara grew into this hardened “cool”-type character while still remaining grounded. I was drawn to her and I still think she’s a lovely woman, but classic Lara is my favourite. -

Apache TOMCAT

LVM Data Migration • XU4 Fan Control • OSX USB-UART interfacing Year Two Issue #22 Oct 2015 ODROIDMagazine Apache TOMCAT Your web server and servlet container running on the world’s most power-efficient computing platform Plex Linux Gaming: Emulate Sega’s last Media console, the Dreamcast Server What we stand for. We strive to symbolize the edge of technology, future, youth, humanity, and engineering. Our philosophy is based on Developers. And our efforts to keep close relationships with developers around the world. For that, you can always count on having the quality and sophistication that is the hallmark of our products. Simple, modern and distinctive. So you can have the best to accomplish everything you can dream of. We are now shipping the ODROID-U3 device to EU countries! Come and visit our online store to shop! Address: Max-Pollin-Straße 1 85104 Pförring Germany Telephone & Fax phone: +49 (0) 8403 / 920-920 email: [email protected] Our ODROID products can be found at http://bit.ly/1tXPXwe EDITORIAL his month, we feature two extremely useful servers that run very well on the ODROID platform: Apache Tom- Tcat and Plex Media Server. Apache Tomcat is an open- source web server and servlet container that provides a “pure Java” HTTP web server environment for Java code to run in. It allows you to write complex web applications in Java without needing to learn a specific server language such as .NET or PHP. Plex Media Server organizes your vid- eo, music, and photo collections and streams them to all of your screens. -

Nintendo Famicom

Nintendo Famicom Last Updated on September 23, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments '89 Dennou Kyuusei Uranai Jingukan 10-Yard Fight Irem 100 Man Dollar Kid: Maboroshi no Teiou Hen Sofel 1942 Capcom 1943: The Battle of Valhalla Capcom 1943: The Battle of Valhalla: FamicomBox Nintendo 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu C*Dream 2010 Street Fighter Capcom 4 Nin uchi Mahjong Nintendo 8 Eyes Seta 8bit Music Power Final: Homebrew Columbus Circle A Ressha de Ikou Pony Canyon Aa Yakyuu Jinsei Icchokusen Sammy Abadox: Jigoku no Inner Wars Natsume Abarenbou Tengu Meldac Aces: Iron Eagle III Pack-In-Video Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Dragons of Flame Pony Canyon Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Heroes of the Lance Pony Canyon Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Hillsfar Pony Canyon Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Pool of Radiance Pony Canyon Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo II HAL Laboratory After Burner Sunsoft Ai Sensei no Oshiete: Watashi no Hoshi Irem Aigiina no Yogen: From The Legend of Balubalouk VIC Tokai Air Fortress HAL Laboratory Airwolf Kyugo Boueki Akagawa Jirou no Yuurei Ressha KING Records Akira Taito Akuma Kun - Makai no Wana Bandai Akuma no Shoutaijou Kemco Akumajou Densetsu Konami Akumajou Dracula Konami Akumajou Special: Boku Dracula Kun! Konami Alien Syndrome Sunsoft America Daitouryou Senkyo Hector America Oudan Ultra Quiz: Shijou Saidai no Tatakai Tomy American Dream C*Dream Ankoku Shinwa - Yamato Takeru Densetsu Tokyo Shoseki Antarctic Adventure Konami Aoki Ookami to Shiroki Mejika: Genchou Hishi Koei Aoki Ookami to Shiroki Mejika: Genghis Khan Koei Arabian Dream Sherazaado Culture Brain Arctic Pony Canyon Argos no Senshi Tecmo Argus Jaleco Arkanoid Taito Arkanoid II Taito Armadillo IGS Artelius Nichibutsu Asmik-kun Land Asmik ASO: Armored Scrum Object SNK Astro Fang: Super Machine A-Wave Astro Robo SASA ASCII This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Third Person : Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives / Edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin

ThirdPerson Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 8 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email [email protected]. This book was set in Adobe Chapparal and ITC Officina on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Third person : authoring and exploring vast narratives / edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-23263-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Electronic games. 2. Mass media. 3. Popular culture. 4. Fiction. I. Harrigan, Pat. II. Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. GV1469.15.T48 2009 794.8—dc22 2008029409 10987654321 Index American Letters Trilogy, The (Grossman), 193, 198 Index Andersen, Hans Christian, 362 Anderson, Kevin J., 27 A Anderson, Poul, 31 Abbey, Lynn, 31 Andrae, Thomas, 309 Abell, A. S., 53 Andrews, Sara, 400–402 Absent epic, 334–336 Andriola, Alfred, 270 Abu Ghraib, 345, 352 Andru, Ross, 276 Accursed Civil War, This (Hull), 364 Angelides, Peter, 33 Ace, 21, 33 Angel (TV show), 4–5, 314 Aces Abroad (Mila´n), 32 Animals, The (Grossman), 205 Action Comics, 279 Aparo, Jim, 279 Adams, Douglas, 21–22 Aperture, 140–141 Adams, Neal, 281 Appeal, 135–136 Advanced Squad Leader (game), 362, 365–367 Appendixes (Grossman), 204–205 Afghanistan, 345 Apple II, 377 AFK Pl@yers, 422 Appolinaire, Guillaume, 217 African Americans Aquaman, 306 Black Lightning and, 275–284 Arachne, 385, 396 Black Power and, 283 Archival production, 419–421 Justice League of America and, 277 Aristotle, 399 Mr. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

Download This PDF File

Vol. 3, No. 2 (2009) http:/www.eludamos.org Generations and Game Localization: An Interview with Alexander O. Smith, Steven Anderson and Matthew Alt Darshana Jayemanne Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture. 2009; 3 (2), p. 135-147 Generations and Game Localization: An Interview with Alexander O. Smith, Steven Anderson and Matthew Alt DARSHANA JAYEMANNE The interplay between the Japanese and Western game industries has been one of the most fruitful mass cultural exchanges of the past few decades. The circulation of gaming products between the two contexts has seen both brilliant successes and dismal failures, but also more than a few unlikely felicities. Shigeru Miyamoto, in his search for an English appellation for Mario’s disgruntled simian antagonist, hit upon the now iconic Donkey Kong. Many gamers will remember wondering how they could set up a match against Shen Long, trembling at the stark realisation that “Someone set us up the bomb,” and taking comfort in Barry Burton’s affirmation of Jill Valentine’s prowess in Resident Evil (Capcom 1997): “Jill, here's a lockpick. It might be handy if you, the master of unlocking, take it with you.” Though his syntactical choices may lead one to certain uncharitable conclusions about Barry, his foresight and canny allocation of limited team resources was in fact indispensable to his colleague’s survival into the game’s sequels. By the time of the GameCube remake (Capcom 2002), Barry had improved his communication skills considerably. While diegetically this may be attributed to robust training policy reform at the Racoon City Police Department, in an extra-diegetic sense can be seen as indicative of broader trends in localisation standards. -

More Than a Game

More than a game prelims.p65 1 13/02/03, 13:59 For Diane and Eve – the people who really matter prelims.p65 2 13/02/03, 13:59 More than a game The computer game as fictional form Barry Atkins Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims.p65 3 13/02/03, 13:59 Copyright © Barry Atkins 2003 The right of Barry Atkins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6364 7 hardback 0 7190 6365 5 paperback First published 2003 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs www.freelancepublishingservices.co.uk Printed in Great Britain by Bell and Bain Ltd, Glasgow prelims.p65 4 13/02/03, 13:59 Contents Acknowledgements page vi 1 The computer game as fictional form 1 The postmodern temptation 8 Reading game-fictions 21 2 Fantastically real: reading Tomb Raider 27 Lara Croft: -

Juuma Houkan Accele Brid Ace Wo Nerae! Acrobat Mission

3X3 EYES - JUUMA HOUKAN ACCELE BRID ACE WO NERAE! ACROBAT MISSION ACTRAISER HOURAI GAKUEN NO BOUKEN! - TENKOUSEI SCRAMBLE AIM FOR THE ACE! ALCAHEST THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN - LETHAL FOES ANGELIQUE ARABIAN NIGHTS - SABAKU NO SEIREI-O ASHITA NO JOE CYBERNATOR BAHAMUT LAGOON BALL BULLET GUN BASTARD!! BATTLE SOCCER - FIELD NO HASHA ANCIENT MAGIC - BAZOO! MAHOU SEKAI BING BING! BINGO BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON - ANOTHER STORY SAILOR MOON R BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON SUPER S - FUWA FUWA PANIC BRANDISH 2 - THE PLANET BUSTER BREATH OF FIRE II - SHIMEI NO KO BS CHRONO TRIGGER - MUSIC LIBRARY CAPTAIN TSUBASA III - KOUTEI NO CHOUSEN CAPTAIN TSUBASA V - HASH NO SHOUGOU CAMPIONE CARAVAN SHOOTING COLLECTION CHAOS SEED - FUUSUI KAIROKI CHOU MAHOU TAIRIKU WOZZ CHRONO TRIGGER CLOCK TOWER CLOCKWERX CRYSTAL BEANS FROM DUNGEON EXPLORER CU-ON-PA SFC CYBER KNIGHT CYBER KNIGHT II - CHIKYUU TEIKOKU NO YABOU CYBORG 009 DAI 3 JI SUPER ROBOT WARS DAI 4 JI SUPER ROBOT WARS DAIKAIJ MONOGATARI DARK HALF DARK LAW - THE MEANING OF DEATH DER LANGRISSER DIGITAL DEVIL STORY 2 - SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI II DONALD DUCK NO MAHOU NO BOUSHI DORAEMON 4 DO RE MI FANTASY - MILON NO DOKIDOKI DAIBOUKEN DOSSUN! GANSEKI BATTLE DR. MARIO DRAGON BALL Z - HYPER DIMENSION DRAGON BALL Z - CHOU SAIYA DENSETSU DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER BUTOUDEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER BUTOUDEN 3 DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER GOKUDEN - TOTSUGEKI HEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER GOKUDEN - KAKUSEI HEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER SAIYA DENSETSU DRAGON QUEST I AND II DRAGON QUEST III - SOSHITE DENSETU E... DRAGON QUEST V - TENKUU NO HANAYOME -

Also in This Issue

ISSUE 11 :: MARCH 2002 STAPLES NOT INCLUDED COMPLETELY FREE* *FOR IGNinsiders :: snowball Also in This Issue :: The Inside Scoop on Acclaim's Vexx :: THPS3 PC :: NBA Inside Drive 2002 Guide :: FFX Secret Locations :: A Look at the Characters of Hunter: The Reckoning http://insider.ign.com IGN.COM unplugged http://insider.ign.com 002 issue 11 :: march 2002 unplugged :: contents 008 Letter from the Editor :: Is it March already? It seems like it's only been a few weeks since we first took our final Xboxes and GameCubes for a test drive -- and now we're almost at the end of the first quarter of the new year. While January and February are traditionally slow months for gamers, 014 things always start to get more interest- ing in March. Ironically, the games that most people are talking about this month aren't from Sony, Nintendo, or Mi- crosoft. Whether it's giving Xbox own- ers the challenging shooter GUNVAL- KYRIE, throwing down the gauntlet on PS2 with Virtua Fighter 4, or broadening GameCube's sports lineup with Soccer Slam, NBA 2K2, and Home Run King, Sega is delivering on its promise to turn heads no matter what platform you own. With that in mind, this issue of IGN Unplugged not only contains an early re- view of Virtua Fighter 4 but also a look at what could be the first true RPG for 055 GameCube, Skies of Arcadia. And it's not all about Sega, of course. Flip through this PDF mag and you will find an in-depth interview with the guys be- hind the promising multi-platformer Vexx, info on gear, movies, and DVDs, as well as a slew of game previews not yet available on our site. -

Sega Dreamcast European PAL Checklist

Console Passion Retro Games The Sega Dreamcast European PAL Checklist www.consolepassion.co.uk □ 102 Dalmatians □ Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 □ Slave Zero □ 18 Wheeler American Pro Tucker □ Jet Set Radio □ Sno Cross: Championship Racing □ 4 Wheel Thunder □ Jimmy White 2: Cueball □ Snow Surfers □ 90 Minutes □ Jo Jo Bizarre Adventure □ Soldier of Fortune □ Aero Wings □ Kao the Kangaroo □ Sonic Adventure □ Aero Wings 2: Air Strike □ Kiss Psycho Circus □ Sonic Adventure 2 □ Alone in the Dark: TNN □ Le Mans 24 Hours □ Sonic Shuffle □ Aqua GT □ Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver □ Soul Calibur □ Army Men: Sarge’s Heroes □ Looney Tunes: Space Race □ Soul Fighter □ Bangai-O □ Magforce Racing □ South Park Rally □ Blue Stinger □ Maken X □ South Park: Chef’s Luv Shack □ Buggy Heat □ Marvel vs Capcom □ Space Channel 5 □ Bust A Move 4 □ Marvel vs Capcom 2 □ Spawn: In the Demon Hand □ Buzz Lightyear of Star Command □ MDK 2 □ Spec Ops 2: Omega Squad □ Caesars Palace 2000 □ Metropolis Street Racer □ Speed Devils □ Cannon Spike □ Midway’s Greatest Hits Volume 1 □ Speed Devils Online □ Capcom vs SNK □ Millennium Soldier: Expendable □ Spiderman □ Carrier □ MoHo □ Spirit of Speed 1937 □ Championship Surfer □ Monaco GP Racing Simulation 2 □ Star Wars: Demolition □ Charge ‘N’ Blast □ Monaco GP Racing Simulation 2 Online □ Star Wars: Episode 1 Racer □ Chicken Run □ Mortal Kombat Gold □ Star Wars: Jedi Power Battles □ Chu Chu Rocket! □ Mr Driller □ Starlancer □ Coaster Works □ MTV Sports Skateboarding □ Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike □ Confidential Mission □ NBA 2K -

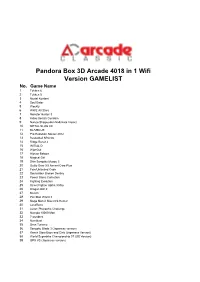

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

Battletech Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade

TM In 3055, a new breed of Inner Sphere BattleMech started rolling off assembling lines—’Mechs specifically designed to counter the Clan invasion—at the same time that second- line Clan ’Mechs began to appear. By 3067 those design have become a staple of the modern battlefield, giving rise to notable MechWarriors and new variants, while the demands of the ever-popular Solaris VII Games have resulted in a plethora of new dueling ’Mechs designed using prototype technology. Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade presents the Solaris VII ’Mechs built using prototype technologies. Upgraded in appearance and technology, the designs first presented in the Solaris VII box set and Solaris: The Reaches are now back in print, along with several new Solaris VII designs. In addition to the upgraded appearance of selected Clan designs, all the art work for Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade is new, providing fresh illustrations of now- classic Inner Sphere BattleMechs and Clan OmniFighters. The ’Mechs in the Solaris VII BattleMechs section are constructed using select equipment found in Tactical Operations. To use those designs, players will need that book. STAR LEAGUE ERA CLAN INVASION ERA JIHAD ERA ® SUCCESSION WARS ERA CIVIL WAR ERA DARK AGE ERA ©2011 The Topps Company Inc. All Rights Reserved. BattleTech Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade, Classic BattleTech, BattleTech, BattleMech, and ’Mech are registered trademarks and/or trademarks of WWW.CATALYSTGAMELABS.COM The Topps Company Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Catalyst Game Labs and the Catalyst Game Labs logo are trademarks of InMediaRes Productions, LLC. Printed in the U.S.A.