Radical Regionalism in the American Midwest, 1930-1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Pynchon: a Brief Chronology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 6-23-2005 Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology Paul Royster University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Royster, Paul, "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology" (2005). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Thomas Pynchon A Brief Chronology 1937 Born Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr., May 8, in Glen Cove (Long Is- land), New York. c.1941 Family moves to nearby Oyster Bay, NY. Father, Thomas R. Pyn- chon Sr., is an industrial surveyor, town supervisor, and local Re- publican Party official. Household will include mother, Cathe- rine Frances (Bennett), younger sister Judith (b. 1942), and brother John. Attends local public schools and is frequent contributor and columnist for high school newspaper. 1953 Graduates from Oyster Bay High School (salutatorian). Attends Cornell University on scholarship; studies physics and engineering. Meets fellow student Richard Fariña. 1955 Leaves Cornell to enlist in U.S. Navy, and is stationed for a time in Norfolk, Virginia. Is thought to have served in the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. 1957 Returns to Cornell, majors in English. Attends classes of Vladimir Nabokov and M. -

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago Pamphlets Explanatory Power I 6 fDK246.S2 M. Dobrov Chto takoe burzhuaziia? [What is the Bourgeoisie?] Petrograd: Petrogr. Torg. Prom. Soiuz, tip. “Kopeika,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 39 fDK246.S2 S.K. Neslukhovskii Chto takoe sotsializm? [What is Socialism?] Petrograd: K-vo “Svobodnyi put’”, [n.d.] Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 10 fDK246.S2 Aleksandra Kollontai Kto takie sotsial-demokraty i chego oni khotiat’? [Who Are the Social Democrats and What Do They Want?] Petrograd: Izdatel’stvo i sklad “Kniga,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets I 7 fDK246.S2 Vatin (V. A. Bystrianskii) Chto takoe kommuna? (What is a Commune?) Petrograd: Petrogradskogo Soveta Rabochikh i Krasnoarmeiskikh Deputatov, 1918 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 32 fDK246.S2 L. Kin Chto takoe respublika? [What is a Republic?] Petrograd: Revoliutsionnaia biblioteka, 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 31 fDK246.S2 G.K. Kryzhitskii Chto takoe federativnaia respublika? (Rossiiskaia federatsiia) [What is a Federal Republic? (The Russian Federation)] Petrograd: Znamenskaia skoropechatnaia, 1917 1 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E42 fDK246.S2 O.A. Vol’kenshtein (Ol’govich): Federalizm v Rossii [Federalism in Russia] Knigoizdatel’stvo “Luch”, [n.d.] fDK246.S2 E33 I.N. Ignatov Gosudarstvennyi stroi Severo-Amerikanskikh Soedinenykh shtatov: Respublika [The Form of Government of the United States of America: Republic] Moscow: t-vo I. D. Sytina, 1917 fDK246.S2 E34 K. Parchevskii Polozhenie prezidenta v demokraticheskoi respublike [The Position of the President in a Democratic Republic] Petrograd: Rassvet, 1917 fDK246.S2 H35 Prof. V.V. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

An American Outsider

Nelson Algren: An American Outsider Bettina Drew VER THE MANY YEARS IHAVE SPENT WRITING AND THINKING ABOUT Nelson Algren, I have always found, in addition to his poetic lyri- clsm, a density and darkness and preoccupation with philosoph- .nl issues that seem fundamentally European rather than Amer- ican. In many ways, Norman Mailer was right when he called Algren "the grand odd-ball of American Ietters."' There is some- thing accurate in the description, however pejorative its intent or meaning at first glance, for Algren held consistently and without doubt to an artistic vision that, above and beyond its naturalism, was at odds with the mainstream of American literature. And cul- ural reasons led to the lukewarm American reception of his work ill the past several decades. As James R. Giles notes in his book Confronting the Horror: The Novels of Nelson Algren, a school of critical thought citing Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman argues that nineteenth-century American liter- ature was dominated by an innocence and an intense faith in in- dividual freedom and human potential. But nineteenth-century American literature was also dominated by an intense focus on the American experience as unique in the world, a legacy, perhaps, of --. the American Revolution against monarchy in favor of democ- racy. Slave narratives, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852),narratives of westward discovery such as Twain's Roughing It (1872), the wilderness tales of James Fenimore Cooper, and Thoreau's stay on Walden Pond were stories that could have taken place only in America-an essentially rural and industrially unde- veloped America. -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

1947 Reprint No Number 28 Pp

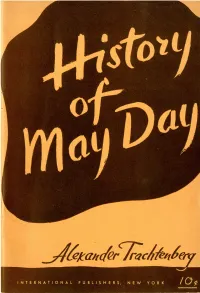

HISTORY OF MAY DAY BY ALEXANDER TRACHTENBERG INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS NEW YORK NOTE History of May Day was first published in 1929 aJild was re issued in many editions, reaching a circulation of over a quarter million copies. It is now published in a revised edition. Copyright, 1947, by INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS CO., INC • ..... 209 PRINTED IN U.S.A. HISTORY OF MAY DAY THE ORIGIN OF MAY DAY is indissolubly bound up with the struggle for the shorter workday-a demand of major political significance for the working class. This struggle is manifest almost from the beginning of the factory system in the United States. Although the demand for higher wages appears to be the most prevalent cause for the early strikes in this country, the question of shorter hours and the right to organize were always kept in the foreground when workers formulated their demands. As exploita tion was becoming intensified and workers were feeling more and more the strain of inhumanly long working hours, the demand for an appreciable reduction of hours became more pronounced. Already at the opening of the 19th century, workers in the United States made known their grievances against working from "sunrise to sunset," the then prevailing workday. Fourteen, six teen and even eighteen hours a day were not uncommon. During the conspiracy trial against the leaders of striking Philadelphia cordwainers in 1806, it was brought out that workers were em ployed as long as nineteen and twenty hours a day. The twenties and thirties are replete with strikes for reduction of hours of work and definite demands for a 10-hour day were put forward in many industrial centers. -

Pynchon in Popular Magazines John K

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar English Faculty Research English 7-1-2003 Pynchon in Popular Magazines John K. Young Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/english_faculty Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Young, John K. “Pynchon in Popular Magazines.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 44.4 (2003): 389-404. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pynchon in Popular Magazines JOHN K. YOUNG Any devoted Pynchon reader knows that "The Secret Integration" originally appeared in The Saturday Evening Post and that portions of The Crying of Lot 49 were first serialized in Esquire and Cavalier. But few readers stop to ask what it meant for Pynchon, already a reclusive figure, to publish in these popular magazines during the mid-1960s, or how we might understand these texts today after taking into account their original sites of publica- tion. "The Secret Integration" in the Post or the excerpt of Lot 49 in Esquire produce different meanings in these different contexts, meanings that disappear when reading the later versions alone. In this essay I argue that only by studying these stories within their full textual history can we understand Pynchon's place within popular media and his responses to the consumer culture through which he developed his initial authorial image. -

Nelson Algren Accuse Playboy Frédéric DUMAS

Éros est mort à Chicago : Nelson Algren accuse Playboy Frédéric DUMAS Nelson Algren fut Lauréat du premier National Book Award en 1950 pour The Man with the Golden Arm, dont l’adaptation cinématographique par Otto Preminger eut un immense succès (avec, dans les rôles principaux, Frank Sinatra et Kim Novak). Malgré son talent d’écrivain, il reste avant tout célèbre pour sa relation amoureuse avec Simone de Beauvoir. À la suite de la publication de Lettres à Nelson Algren, il y a quatre ans, la BBC, les télévisions américaine et française ont diffusé plusieurs émissions, consacrées à cette relation, qui a profondément marqué les œuvres respectives des deux auteurs. Sur le plan anecdotique, l’évocation d’Algren dans le cadre de ce colloque est d’autant plus justifiée, qu’Algren est définitivement rentré dans l’histoire pour avoir donné à Simone de Beauvoir son premier orgasme ! Entre 1935 et 1981, date de sa mort, il a publié neuf ouvrages : des romans, un long poème en prose, un recueil de nouvelles toujours populaire (The Neon Wilderness) et quelques ouvrages inclassables, mêlant entre autres les récits de voyages, la poésie, la nouvelle et le récit auto- biographique. Pour Algren, les relations sociales sont devenues vides de sens en raison de la toute puissance du monde des affaires et de son conformisme, incapables de donner un sens à l’existence. Le “business” propose une seule façon d’appréhender la vie, exempte de tous les aléas inhérents aux affres des sentiments ou des plaisirs naturels : ils seraient susceptibles de mettre en danger le confort de l’individu, et par conséquent, indirectement, la pérennité du système. -

Representations of Women and Aspects of Their Agency

REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN AND ASPECTS OF THEIR AGENCY IN MALE AUTHORED PROLETARIAN EXPERIMENTAL NOVELS FROM THIRTIES AMERICA By Anoud Ziad Abdel-Qader Al-Tarawneh A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Drama, & American and Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the layered representations of women, their agency, and their class awareness in four leftist experimental novels from 1930s America: Langston Hughes’ Not Without Laughter, Jack Conroy’s The Disinherited, John Dos Passos’ The Big Money, and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. It argues that the histories these novels engage, the forms they integrate, and the societal norms they explore enable their writers to offer a complex, distinct, sense of female representation and agency. All four novels present stereotyped or sentimentalised portrayals of women from the traces of early twentieth-century popular culture, a presentation which the novels’ stories explore through nuanced, mobilised, or literally as well as figuratively politicised images of women. -

Dictatorsh I P and Democracy Soviet Union

\\. \ 001135 DICTATORSH IP AND DEMOCRACY IN THE SOVIET UNION FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SOCIALIST· LABOR CO~lECTlON by Anna Louise Strong No. 40 INTERNATIONAL PAMPHLETS 779 Broadway New York 5 cents PUBLISHERS' NOTE THIS pamphlet, prepared under the direction of Labor Re search Association, is one of a series published by Interna tional Pamphlets, 799 Broadway, New York, from whom additional copies may be obtained at five cents each. Special rates on quantity orders. IN THIS SERIES OF PAMPHLETS I. MODERN FARMING-SOVIET STYLE, by Anna Louise Strong IO¢ 2. WAR IN THE FAR EAST, by Henry Hall. IO¢ 3. CHEMICAL WARFARE, by Donald Cameron. "" IO¢ 4. WORK OR WAGES, by Grace Burnham. .. .. IO¢ 5. THE STRUGGLE OF THE MARINE WORKERS, by N. Sparks IO¢ 6. SPEEDING UP THE WORKERS, by James Barnett . IO¢ 7. YANKEE COLONIES, by Harry Gannes 101 8. THE FRAME-UP SYSTEM, by Vern Smith ... IO¢ 9. STEVE KATOVIS, by Joseph North and A. B. Magil . IO¢ 10. THE HERITAGE OF GENE DEllS, by Alexander Trachtenberg 101 II. SOCIAL INSURANCE, by Grace Burnham. ...... IO¢ 12. THE PARIS COMMUNE--A STORY IN PICTURES, by Wm. Siegel IO¢ 13. YOUTH IN INDUSTRY, by Grace Hutchins .. IO¢ 14. THE HISTORY OF MAY DAY, by Alexander Trachtenberg IO¢ 15. THE CHURCH AND THE WORKERS, by Bennett Stevens IO¢ 16. PROFITS AND WAGES, by Anna Rochester. IO¢ 17. SPYING ON WORKERS, by Robert W. Dunn. IO¢ 18. THE AMERICAN NEGRO, by James S. Allen . IO¢ 19. WAR IN CHINA, by Ray Stewart. .... IO¢ 20. SOVIET CHiNA, by M. James and R. -

LP001061 0.Pdf

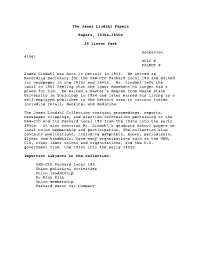

The James Lindahl Papers Papers, 1930s-1950s 29 linear feet Accession #1061 OCLC # DALNET # James Lindahl was born in Detroit in 1911. He served as Recording Secretary for the UAW-CIO Packard Local 190 and edited its newspaper in the 1930s and 1940s. Mr. Lindahl left the local in 1951 feeling that the labor movement no longer had a place for him. He earned a Master's degree from Wayne State University in Sociology in 1954 and later earned his living as a self-employed publisher in the Detroit area in various fields including retail, banking, and medicine. The James Lindahl Collection contains proceedings, reports, newspaper clippings, and election information pertaining to the UAW-CIO and its Packard Local 190 from the 1930s into the early 1950s. It also contains Mr. Lindahl's graduate school papers on local union membership and participation. The collection also contains publications, including pamphlets, books, periodicals, flyers and handbills, from many organizations such as the UAW, CIO, other labor unions and organizations, and the U.S. government from the 1930s into the early 1950s. Important subjects in the collection: UAW-CIO Packard Local 190 Union political activities Union leadership Ku Klux Klan Union membership Packard Motor Car Company 2 James Lindahl Collection CONTENTS 29 Storage Boxes Series I: General files, 1937-1953 (Boxes 1-6) Series II: Publications (Boxes 7-29) NON-MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL Approximately 12 union contracts and by-laws were transferred to the Archives Library. 3 James Lindahl Collection Arrangement The collection is arranged into two series. In Series I (Boxes 1-6), folders are simply listed by location within each box.