The Secret Faces of Inscrutable Poets in Nelson Algren's Chicago: City On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermezzo May/June 2021

Virtual Membership Meeting: Virtual Membership Meeting: May/June 2021 Monday, May 10th, 2021 Monday, June 14th, 2021 Vol. 81 No. 3 @ 6:00 pm @ 6:00 pm Musician Profile: Chicago’s Jimmy Pankow and Lee Loughnane Page 6 Looking Back Page 11 The Passing of Dorothy Katz Page 28 Local 10-208 of AFM CHICAGO FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICERS – DELEGATES 2020-2022 Terryl Jares President Leo Murphy Vice-President B.J. Levy Secretary-Treasurer BOARD OF DIRECTORS FROM THE PRESIDENT Robert Bauchens Nick Moran Rich Daniels Charles Schuchat Jeff Handley Joe Sonnefeldt Janice MacDonald FROM THE VICE-PRESIDENT CONTRACT DEPARTMENT Leo Murphy – Vice-President ASSISTANTS TO THE PRESIDENT - JURISDICTIONS FROM THE SECRETARY-TREASURER Leo Murphy - Vice-President Supervisor - Entire jurisdiction including theaters (Cell Phone: 773-569-8523) Dean Rolando CFM MUSICIANS Recordings, Transcriptions, Documentaries, Etc. (Cell Phone: 708-380-6219) DELEGATES TO CONVENTIONS OF THE RESOLUTION ILLINOIS STATE FEDERATION OF LABOR AND CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS Terryl Jares Leo Murphy WHO, WHERE, WHEN B.J. Levy DELEGATES TO CHICAGO FEDERATION OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL UNION COUNCIL Rich Daniels Leo Murphy LOOKING BACK Terryl Jares DELEGATES TO CONVENTIONS OF THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS Rich Daniels B.J. Levy HEALTH CARE UPDATE Terryl Jares Leo Murphy Alternate: Charles Schuchat PUBLISHER, THE INTERMEZZO FAIR EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES COMMITTEE Terryl Jares CO-EDITORS, THE INTERMEZZO Sharon Jones Leo Murphy PRESIDENTS EMERITI CFM SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS Gary Matts Ed Ward VICE-PRESIDENT EMERITUS Tom Beranek OBITUARIES SECRETARY-TREASURER EMERITUS Spencer Aloisio BOARD OF DIRECTORS EMERITUS ADDRESS AND PHONE CHANGES Bob Lizik Open Daily, except Saturday, Sunday and Holidays Office Hours 9 A.M. -

Thomas Pynchon: a Brief Chronology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 6-23-2005 Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology Paul Royster University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Royster, Paul, "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology" (2005). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Thomas Pynchon A Brief Chronology 1937 Born Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr., May 8, in Glen Cove (Long Is- land), New York. c.1941 Family moves to nearby Oyster Bay, NY. Father, Thomas R. Pyn- chon Sr., is an industrial surveyor, town supervisor, and local Re- publican Party official. Household will include mother, Cathe- rine Frances (Bennett), younger sister Judith (b. 1942), and brother John. Attends local public schools and is frequent contributor and columnist for high school newspaper. 1953 Graduates from Oyster Bay High School (salutatorian). Attends Cornell University on scholarship; studies physics and engineering. Meets fellow student Richard Fariña. 1955 Leaves Cornell to enlist in U.S. Navy, and is stationed for a time in Norfolk, Virginia. Is thought to have served in the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. 1957 Returns to Cornell, majors in English. Attends classes of Vladimir Nabokov and M. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago As Seen in the Naming of Schools

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1990 A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago as Seen in the Naming of Schools Mary McFarland-McPherson Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation McFarland-McPherson, Mary, "A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago as Seen in the Naming of Schools" (1990). Dissertations. 2709. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2709 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1990 Mary McFarland-McPherson A SOCIO-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC EDUCATION IN CHICAGO AS SEEN IN THE NAMING OF SCHOOLS by Mary McFarland-McPherson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 1990 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer sincerely appreciates the patience, · endurance and assistance afforded by the many persons who extended their unselfish support of this dissertation. Special orchids to Dr. Joan K. Smith for her untiring guidance, encouragement, expertise, and directorship. Gratitude is extended to Dr. Gerald L. Gutek and Rev. F. Michael Perko, S.J. who, as members of this committee provided invaluable personal and professional help and advice. The writer is thankful for the words of wisdom and assistance provided by: Mr. -

Pete Segall. the Voice of Chicago in the 20Th Century: a Selective Bibliographic Essay

Pete Segall. The Voice of Chicago in the 20th Century: A Selective Bibliographic Essay. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. December, 2006. 66 pages. Advisor: Dr. David Carr Examining the literature of Chicago in the 20th Century both historically and critically, this bibliography attempts to find commonalities of voice in a list of selected works. The paper first looks at Chicago in a broader context, focusing particularly on perceptions of the city: both Chicago’s image of itself and the world’s of it. A series of criteria for inclusion in the bibliography are laid out, and with that a mention of several of the works that were considered but ultimately disqualified or excluded. Before looking into the Voice of the city, Chicago’s history is succinctly summarized in a bibliography of general histories as well as of seminal and crucial events. The bibliography searching for Chicago’s voice presents ten books chronologically, from 1894 to 2002, a close examination of those works does reveal themes and ideas integral to Chicago’s identity. Headings: Chicago (Ill.) – Bibliography Chicago (Ill.) – Bibliography – Critical Chicago (Ill.) – History Chicago (Ill.) – Fiction THE VOICE OF CHICAGO IN THE 20TH CENTURY: A SELECTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY by Pete Segall A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina December 2006 Approved by _______________________________________ Dr. David Carr 1 INTRODUCTION As of this moment, a comprehensive bibliography on the City of Chicago does not exist. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

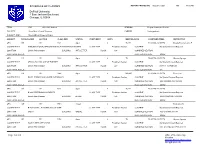

SCHEDULE of CLASSES Depaul University 1 East Jackson

SCHEDULE OF CLASSES REPORT PRINTED ON: August 13, 2021 AT: 11:42 AM DePaul University 1 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, IL 60604 TERM: 1080 2021-2022 Autumn SESSION: Regular Academic Session COLLEGE: Liberal Arts & Social Sciences CAREER: Undergraduate SUBJECT AREA: African&Black Diaspora Studies SUBJECT CATALOG NBR SECTION CLASS NBR STATUS COMPONENT UNITS MEETING DAYS START/END TIMES INSTRUCTOR ABD 100 101 1821 Open 4 TU TH 11:20 AM - 12:50 PM Moody-Freeman,Julie E COURSE TITLE: INTRODUCTION TO AFRICAN AND BLACK DIASPORA STUDIES CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 408 COMBINED SECTION: ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: SSMW ABD 211 101 1638 Open 4 TU 05:45 PM - 09:00 PM Otunnu,Ogenga COURSE TITLE: AFRICA TO 1800: AGE OF EMPIRES CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 207 COMBINED SECTION: HST131 701/ABD 211 ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: UP ABD 229 101 2088 Open 4 MO WE 11:20 AM - 12:50 PM Pierce,Lori COURSE TITLE: RACE, SCIENCE AND WHITE SUPREMACY CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 109 COMBINED SECTION: ABD 229/AMS 297/PAX 290 ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: SSMW ABD 236 101 6821 Open 4 TU TH 01:00 PM - 02:30 PM COURSE TITLE: BLACK FREEDOM MOVEMENTS CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: LEVAN ROOM: -

Angela Jackson

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. ANGELA JACKSON A renowned Chicago poet, novelist, play- wright, and biographer, Angela Jackson published her first book while still a stu- dent at Northwestern University. Though Jackson has achieved acclaim in multi- ple genres, and plans in the near future to add short stories and memoir to her oeuvre, she first and foremost considers herself a poet. The Poetry Foundation website notes that “Jackson’s free verse poems weave myth and life experience, conversation, and invocation.” She is also renown for her passionate and skilled Photo by Toya Werner-Martin public poetry readings. Born on July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi, Jackson moved with her fam- ily to Chicago’s South Side at the age of one. Jackson’s father, George Jackson, Sr., and mother, Angeline Robinson, raised nine children, of which Angela was the middle child. Jackson did her primary education at St. Anne’s Catholic School and her high school work at Loretto Academy, where she earned a pre-medicine scholar- ship to Northwestern University. Jackson switched majors and graduated with a B.A. in English and American Literature from Northwestern University in 1977. She later earned her M.A. in Latin American and Caribbean studies from the University of Chicago, and, more recently, received an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Bennington College. While at Northwestern, Jackson joined the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), where she matured under the guidance of legendary literary figures such as Hoyt W Fuller. -

Reprinted by Permission of Modern Drummer Publications, Inc

Reprinted by permission of Modern Drummer Publications, Inc. Copyright 2006. Reprinted by permission of Modern Drummer Publications, Inc. Copyright 2006. t’s not often in a career as a journalist that Today, it’s difficult sitting with Danny, hear- you feel as though you’ve reached the core ing a story of betrayal and personal agony. But of someone’s being, as though you’ve been he’s the perfect example of how one endures, Igiven an honest look into someone’s soul. self-investigates, points the right fingers (even It’s rare that an artist will be so open and self- at himself), and gets through it. Listening to analytical that he’ll give you a true picture of him tell the story of his recent and reclusive what he’s been through. Well, in the following years was upsetting. But I also had a sense of interview, Danny Seraphine bares his soul. relief knowing that the musician I always Danny Seraphine was my first cover story for admired was speaking from the heart and was Modern Drummer, in the December ’78/January finally emerging from what was obviously a ’79 issue. Like millions of fans around the terrible time in his life. world, I loved Chicago. Their music was an “I went from one lifestyle to another,” innovative fusion of rock and jazz, featuring Seraphine says of his firing. “I was in a great tight horn arrangements in a rock setting and band, and then I wasn’t. It was as if the Lord great songwriting. At the center of it all was a had flicked a switch and said, ‘Guess what? Your drummer with inventive chops and a swing sen- life is changing.’ I went from one extreme to sibility. -

CHNA‐South Suburban Chicago

CHNA-South Suburban Chicago 1 CHNA‐South Suburban Chicago Franciscan St. James Health‐Olympia Fields & Chicago Heights Spring 2016 CHNA-South Suburban Chicago 3 Community Health Needs Assessment CONTENTS Community Health Needs Assessment 2 Executive Summary 4 Franciscan St. James Health‐Olympia Fields & Chicago Heights 5 Approach and Methodology 7 Communities We Serve 9 Special Populations 9 Social Determinants of Health 10 General Health 11 Overall Physical Health 14 Overall Mental Health 15 Chronic Disease, Mortality, Morbidity 15 Leading Causes of Death 15 Accidents, Injuries, and Homicide 16 Cancer 16 Cardiovascular 18 Diabetes 19 Infectious Disease 20 Neurological 20 Respiratory 20 Rheumatic/Joint Related 21 CHNA-South Suburban Chicago 3 Behavioral Health 21 Substance Abuse 22 Suicide 22 Pre‐Natal through 18 Years of Age 23 Pre‐Natal Care 24 Birth Outcomes 24 Youth Indicators 24 Modifiable Health Risks 25 Weight 25 Physical Activity 25 Nutrition 26 Substance Abuse 26 Tobacco Use 27 Oral Health 27 Access to Health Care Challenges 28 Health Professions Shortage Areas 28 Insurance/Payment 28 Transportation 28 Summary 28 Data Gaps and Challenges 29 Response to Findings 29 CHNA-South Suburban Chicago 3 Executive Summary The Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) is designed to provide an understanding of the current health status and needs of the residents in the communities served by Franciscan St. James Health (FSJH‐Olympia Fields and Chicago Heights). This report meets the current Internal Revenue Service’s requirement for tax‐exempt hospitals, which is based on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. More importantly, this document assists FSJH in providing essential services to those most in need.