Shark Tooth Weapons from the 19Th Century Reflect Shifting Baselines in Central Pacific Predator Assemblies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teeth Penetration Force of the Tiger Shark Galeocerdo Cuvier and Sandbar Shark Carcharhinus Plumbeus

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 91, 460–472 doi:10.1111/jfb.13351, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Teeth penetration force of the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus J. N. Bergman*†‡, M. J. Lajeunesse* and P. J. Motta* *University of South Florida, Department of Integrative Biology, 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL 33620, U.S.A. and †Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 100 Eighth Avenue S.E., Saint Petersburg, FL 33701, U.S.A. (Received 16 February 2017, Accepted 15 May 2017) This study examined the minimum force required of functional teeth and replacement teeth in the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and the sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus to penetrate the scales and muscle of sheepshead Archosargus probatocephalus and pigfish Orthopristis chrysoptera. Penetra- tion force ranged from 7·7–41·9and3·2–26·3 N to penetrate A. probatocephalus and O. chrysoptera, respectively. Replacement teeth required significantly less force to penetrate O. chrysoptera for both shark species, most probably due to microscopic wear of the tooth surfaces supporting the theory shark teeth are replaced regularly to ensure sharp teeth that are efficient for prey capture. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: biomechanics; bite force; Elasmobranchii; teleost; tooth morphology. INTRODUCTION Research on the functional morphology of feeding in sharks has typically focused on the kinematics and mechanics of cranial movement (Ferry-Graham, 1998; Wilga et al., 2001; Motta, 2004; Huber et al., 2005; Motta et al., 2008), often neglecting to integrate the function of teeth (but see Ramsay & Wilga, 2007; Dean et al., 2008; Whitenack et al., 2011). -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

State of Oregon The ORE BIN· Department of Geology Volume 34,no. 10 and Mineral Industries 1069 State Office BI dg. October 1972 Portland Oregon 97201 FOSSil SHARKS IN OREGON Bruce J. Welton* Approximately 21 species of sharks, skates, and rays are either indigenous to or occasionally visit the Oregon coast. The Blue Shark Prionace glauca, Soup-fin Shark Galeorhinus zyopterus, and the Dog-fish Shark Squalus acanthias commonly inhabit our coastal waters. These 21 species are represented by 16 genera, of which 10 genera are known from the fossi I record in Oregon. The most common genus encountered is the Dog-fish Shark Squalus. The sharks, skates, and rays, (all members of the Elasmobranchii) have a fossil record extending back into the Devonian period, but many major groups became extinct before or during the Mesozoic. A rapid expansion in the number of new forms before the close of the Mesozoic gave rise to practically all the Holocene families living today. Paleozoic shark remains are not known from Oregon, but teeth of the Cretaceous genus Scapanorhyn chus have been collected from the Hudspeth Formation near Mitchell, Oregon. Recent work has shown that elasmobranch teeth occur in abundance west of the Cascades in marine Tertiary strata ranging in age from late Eocene to middle Miocene (Figures 1 and 2). All members of the EIasmobranchii possess a cartilaginous endoskeleton which deteriorates rapidly upon death and is only rarely preserved in the fossil record. Only under exceptional conditions of preservation, usually in a highly reducing environment, will cranial or postcranial elements be fossilized. -

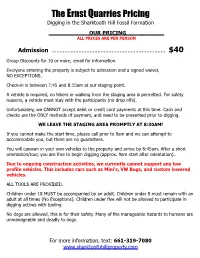

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation OUR PRICING ALL PRICES ARE PER PERSON Admission ........................................................................ $40 Group Discounts for 10 or more, email for information. Everyone entering the property is subject to admission and a signed waiver, NO EXCEPTIONS. Check-in is between 7:45 and 8:15am at our staging point. A vehicle is required, no hikers or walking from the staging area is permitted. For safety reasons, a vehicle must stay with the participants (no drop offs). Unfortunately, we CANNOT accept debit or credit card payments at this time. Cash and checks are the ONLY methods of payment, and need to be presented prior to digging. WE LEAVE THE STAGING AREA PROMPTLY AT 8:30AM! If you cannot make the start time, please call prior to 8am and we can attempt to accommodate you, but there are no guarantees. You will caravan in your own vehicles to the property and arrive by 8:45am. After a short orientation/tour, you are free to begin digging (approx. 9am start after orientation). Due to ongoing construction activities, we currently cannot support any low profile vehicles. This includes cars such as Mini's, VW Bugs, and custom lowered vehicles. ALL TOOLS ARE PROVIDED. Children under 18 MUST be accompanied by an adult. Children under 8 must remain with an adult at all times (No Exceptions). Children under five will not be allowed to participate in digging actives with tooling. No dogs are allowed, this is for their safety. Many of the manageable hazards to humans are unmanageable and deadly to dogs. -

Re-Evaluation of Pachycormid Fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany

Editors' choice Re-evaluation of pachycormid fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany ERIN E. MAXWELL, PAUL H. LAMBERS, ADRIANA LÓPEZ-ARBARELLO, and GÜNTER SCHWEIGERT Maxwell, E.E., Lambers, P.H., López-Arbarello, A., and Schweigert G. 2020. Re-evaluation of pachycormid fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 65 (3): 429–453. Pachycormidae is an extinct group of Mesozoic fishes that exhibits extensive body size and shape disparity. The Late Jurassic record of the group is dominated by fossils from the lithographic limestone of Bavaria, Germany that, although complete and articulated, are not well characterized anatomically. In addition, stratigraphic and geographical provenance are often only approximately known, making these taxa difficult to place in a global biogeographical context. In contrast, the late Kimmeridgian Nusplingen Plattenkalk of Baden-Württemberg is a well-constrained locality yielding hundreds of exceptionally preserved and prepared vertebrate fossils. Pachycormid fishes are rare, but these finds have the potential to broaden our understanding of anatomical variation within this group, as well as provide new information regarding the trophic complexity of the Nusplingen lagoonal ecosystem. Here, we review the fossil record of Pachycormidae from Nusplingen, including one fragmentary and two relatively complete skulls, a largely complete fish, and a fragment of a caudal fin. These finds can be referred to three taxa: Orthocormus sp., Hypsocormus posterodorsalis sp. nov., and Simocormus macrolepidotus gen. et sp. nov. The latter taxon was erected to replace “Hypsocormus” macrodon, here considered to be a nomen dubium. Hypsocormus posterodorsalis is known only from Nusplingen, and is characterized by teeth lacking apicobasal ridging at the bases, a dorsal fin positioned opposite the anterior edge of the anal fin, and a hypural plate consisting of a fused parhypural and hypurals. -

The Truth About Sharks the Story of the Sea Turtle the World of Whales

The Truth About Sharks Sharks are magnificent, but misunderstood creatures that are unfortunately being pushed to the brink of extinction due to overfishing and poor international management. This program highlights the beauty and importance of these animals by showing the incredible rich diversity of shark species and their unique adaptations. Students will rotate through hands-on stations in small groups that involve shark tooth and jaw morphology, shark identification, and shark sensory systems. The session culminates in a discussion about the critical need for conservation of many shark species and what students, no matter where they live, can do to help. The Story of the Sea Turtle Sea turtles are one of the most ancient creatures on Earth, yet we are still learning more and more about them every day. This program covers the life history, ecology, behavior, and unique adaptations of these extraordinary marine animals. Hands-on activities will highlight nesting behavior, sea turtle predators, how hatchings make it to the ocean, and how they are able to return to the same nesting beaches as adults. Students will have sea turtle models to study and even get a chance to experience what it is like for a sea turtle biologist studying these animals in the wild. The session ends in a discussion on current sea turtle conservation measures and how students can help protect marine life. The World of Whales Whales are found in every ocean region and are the largest mammals on the planet, yet we still have much to learn about these magnificent creatures. This program highlights the rich diversity of whale species and their unique adaptations that allow them to grow to mind-boggling dimensions, dive deep underwater, survive in cold-water habitats, and even sing elaborate songs to each other! Through hands-on activities, students will learn about whale feeding and communication strategies, and how scientists study these incredible animals in the wild. -

Semionotiform Fish from the Upper Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania)

Mitt. Mus. Nat.kd. Berl., Geowiss. Reihe 2 (1999) 135-153 19.10.1999 Semionotiform Fish from the Upper Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) Gloria Arratial & Hans-Peter Schultze' With 12 figures Abstract The late Late Jurassic fishes collected by the Tendaguru expeditions (1909-1913) are represented only by a shark tooth and various specimens of the neopterygian Lepidotes . The Lepidotes is a new species characterized by a combination of features such as the presence of scattered tubercles in cranial bones of adults, smooth ganoid scales, two suborbital bones, one row of infraorbital bones, non-tritoral teeth, hyomandibula with an anteriorly expanded membranous outgrowth, two extrascapular bones, two postcleithra, and the absence of fringing fulcra on all fins. Key words: Fishes, Actinopterygii, Semionotiformes, Late Jurassic, East-Africa . Zusammenfassung Die spätoberjurassischen Fische, die die Tendaguru-Expedition zwischen 1909 und 1913 gesammelt hat, sind durch einen Haizahn und mehrere Exemplare des Neopterygiers Lepidotes repräsentiert. Eine neue Art der Gattung Lepidotes ist be- schrieben, sie ist durch eine Kombination von Merkmalen (vereinzelte Tuberkel auf den Schädelknochen adulter Tiere, glatte Ganoidschuppen, zwei Suborbitalia, eine Reihe von Infraorbitalia, nichttritoriale Zähne, Hyomandibulare mit einer membra- nösen nach vorne gerichteten Verbreiterung, zwei Extrascapularia, zwei Postcleithra und ohne sich gabelnde Fulkren auf dem Vorderrand der Flossen) gekennzeichnet. Schlüsselwörter: Fische, Actinopterygii, Semionotiformes, Oberer Jura, Ostafrika. Introduction margin, crescent shaped lateral line pore, and the number of scales in vertical and longitudinal At the excavations of the Tendaguru expeditions rows), and on the shape of teeth (non-tritoral) . (1909-1913), fish remains were collected to- However, the Tendaguru lepidotid differs nota- gether with the spectacular reptiles in sediments bly from L. -

Stomach Contents of the Archaeocete Basilosaurus Isis: Apex Predator in Oceans of the Late Eocene

RESEARCH ARTICLE Stomach contents of the archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene 1☯ 2³ 3³ 3☯ Manja VossID *, Mohammed Sameh M. Antar , Iyad S. Zalmout , Philip D. Gingerich 1 Museum fuÈr Naturkunde Berlin, Leibniz-Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Berlin, Germany, 2 Department of Geology and Paleontology, Nature Conservation Sector, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency, Cairo, Egypt, 3 Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America a1111111111 a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 Abstract Apex predators live at the top of an ecological pyramid, preying on animals in the pyramid OPEN ACCESS below and normally immune from predation themselves. Apex predators are often, but not Citation: Voss M, Antar MSM, Zalmout IS, always, the largest animals of their kind. The living killer whale Orcinus orca is an apex pred- Gingerich PD (2019) Stomach contents of the ator in modern world oceans. Here we focus on an earlier apex predator, the late Eocene archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene. PLoS ONE 14(1): archaeocete Basilosaurus isis from Wadi Al Hitan in Egypt, and show from stomach con- e0209021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. tents that it fed on smaller whales (juvenile Dorudon atrox) and large fishes (Pycnodus pone.0209021 mokattamensis). Our observations, the first direct evidence of diet in Basilosaurus isis, con- Editor: Carlo Meloro, Liverpool John Moores firm a predator-prey relationship of the two most frequently found fossil whales in Wadi Al- University, UNITED KINGDOM Hitan, B. -

Biology of the White Shark

BIOLOGY OF THE WHITE SHARK A SYMPOSIUM MEMOIRS OF THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES VOLUME 9 (24 May 1985) MEMOIRS OF THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The MEMOIRS of the Southern California Academy of Sciences is a series begun in 1938 and published on an irregular basis thereafter. It is intended that each article will continue to be of a monographic nature, and each will constitute a full volume in itself. Contribution to the MEMOIRS may be in any of the fields of science, by any member of the Academy. Acceptance of papers will be determined by the amount and character of new information and the form in which it is presented. Articles must not duplicate, in any substantial way, material that is published elsewhere. Manuscripts must conform to MEMOIRS style of volume 4 or later, and may be examined for scientific content by members of the Publications Committee other than the Editor or be sent to other competent critics for review. Because of the irregular nature of the series, authors are urged to contact the Editor before submitting their manuscript. Gretchen Sibley Editor Jeffrey A. Seigel Camm C. Swift Assistant Editors Communications concerning the purchase of the MEMOIRS should be directed to the Treasurer, Southern California Academy of Sciences, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Exposition Park, Los Angeles, California 90007. Communications concerning manuscripts should be directed to Gretchen Sibley, also at the Museum. CONTENTS FOREWORD On 7 May 1983 a symposium entitled “Biology of the White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias)” was held during the annual meeting of the Southern California Academy of Sciences at California State University Fullerton. -

Managing Sustainable Shark Fishing in the Mariana Archipelago

Managing Sustainable Shark Fishing in the Mariana Archipelago August 2013 Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 1164 Bishop St., Ste. 1400 Honolulu, Hawai’i, 96813 A report of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 1164 Bishop Street, Suite 1400, Honolulu, HI 96813 Prepared by Max Markrich © Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 2013. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council ISBN 978-1-944827-54-0 Introduction This white paper explores the potential for sustainable shark fishing within the US EEZ surrounding the Mariana Archipelago and adjacent high seas. Marianas fishery participants have made it known to the Council that high levels of shark populations in the Marianas Archipelago are believed to occur, resulting in depredation of target catches when pelagic trolling and bottomfishing. In addition, in mid-2000s, the USCG and NOAA successfully apprehended illegal foreign fishing vessels targeting sharks in the Mariana Archipelago, which also suggests commercially viable catch rates. Attempts to establish a pelagic longline fishery within the Marianas Archipelago may consider harvesting sharks as well as the more valuable tunas and billfish species. The purpose and need for this paper is to: Provide the rationale for a systematic survey of shark resources in the US EEZ around the Mariana Islands Describe relevant information on shark fisheries and markets, Identify potential management options for Council consideration with regards the harvests of sharks in the Marianas Archipelago. Background Information Sharks continue to be the focus of much concern from conservation groups, due to the vulnerability of some shark populations to fishing and increasing demand for shark products, (TRAFFIC 2006; Worm et al 2013) especially with the rise in wealth in China (Bain & Company 2011). -

Ultrastructure of the Enamel Layer in Developing Teeth of the Shark Carcharhinus Menisorrah

ULTRASTRUCTURE OF THE ENAMEL LAYER IN DEVELOPING TEETH OF THE SHARK CARCHARHINUS MENISORRAH N. E. KEMP and J. H. PARK bepartment of Zoology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104, U.S.A.. and College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea Summary-The first two rows of teeth at the posterior end of the dental lamina in a 60 cm speci- men of Curcharhinus menisorrah were uncalcified, but calcification had begun in the tooth--cap layor at the tips of third-row teeth. Enamel crystals developed within hollow enamelinc hbrils (tubules) which polymerized beneath the basement menbrane underlying ameloblasts. Vesicles containing fine granules were present in the apical cytoplasm of ameloblasts in tooth buds prior to calcification. Fine granular material accumulated extracellularly between ameloblasts and basement membrane, and also in the enameline matrix on the pulpal side of the basement mem- brane. The morphology suggests that ameloblasts secrete a granular precursor for the mineraliz- ing enameline fibrils. Enamel crystals with their fibrous coatings were tightly packed in miner- alizing zones. Crystals became indefinitely long and equilaterally hexagonal in cross section. They were aligned in parallel within bundles of fibrils interwoven in the mineralizing zones. Odontoblast processes and myelinated nerve fibres penetrated into the cap layer between, mineralizing zones. Giant fibres with a banding periodicity of 14.5 nm occurred in the partition- ing matrix between zones of mineralization. Their origin and nature are uncertain. Conventional collagen fibrils developed in the connective tissue within the base of the tooth. and in dentine after it began to differentiate. Crystals of mineralized dentine were needle-shaped as in mam- mals The cap layer of the sharks tooth is considered to be composed of tubular enamel in which the mineralized zones are probably homologous with mammalian enamel, but which is pene- trated by odontoblast processes of mesoderma! origin. -

Ancient 'Living Fossil' Fish Has Scales That Act As Adaptable Armour | New Scientist

2/13/2019 Ancient 'living fossil' fish has scales that act as adaptable armour | New Scientist DAILY NEWS 9 October 2018 Ancient ‘living fossil’ sh has scales that act as adaptable armour Wrapped in adaptable armour Getty By Chelsea Whyte The coelacanth sh is a living fossil, its appearance little changed in hundreds of millions of years. A new analysis of its scaly armour may reveal how it has stuck around for so long. “Nature seems to generate combinations of properties that we have great difculty with. I’m interested in how strong a material is and also how tough,” says Robert Ritchie at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “That combination is incompatible in synthetic materials, but nature does it with ease.” https://www.newscientist.com/article/2181651-ancient-living-fossil-fish-has-scales-that-act-as-adaptable-armour/ 1/3 2/13/2019 Ancient 'living fossil' fish has scales that act as adaptable armour | New Scientist He and his colleagues examined scales from a coelacanth that had been preserved at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography for 45 years – they couldn’t use a sample from a living or recently deceased sh because coelacanths are endangered. Ads by ZEDO Learn More Spiral staircase When they CT scanned the scales, they found a surprisingly complex inner structure. On top is a tough mineral layer, and beneath there are bundles of collagen – the stuff that gives your skin its resilience – in a twisted structure similar to a spiral staircase. When pressure is applied to the scales, as it would be when a predator bites a coelacanth, the energy is absorbed by the collagen bundles. -

Convergent Evolution in Tooth Morphology of Filter Feeding Lamniform Sharks

CONVERGENT EVOLUTION IN TOOTH MORPHOLOGY OF FILTER FEEDING LAMNIFORM SHARKS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science By MICHAELA GRACE MITCHELL B.S., Northern Kentucky University, 2014 2016 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL November 4, 2016 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Michaela Grace Mitchell ENTITLED Convergent Evolution in Tooth Morphology of Filter Feeding Lamniform Sharks BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science. Charles N. Ciampaglio, Ph.D. Thesis Director David F. Dominic, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences Committee on Final Examination Charles N. Ciampaglio, Ph.D. Stephen J. Jacquemin, Ph.D. Stacey A. Hundley, Ph.D. David A. Schmidt, Ph.D. Robert E. W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Mitchell, Michaela Grace. M.S. Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Wright State University, 2016. Convergent Evolution in Tooth Morphology of Filter Feeding Lamniform Sharks. The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios) are two species of filter feeding sharks, both belonging to the order Lamniformes. There are two conflicting hypotheses regarding the origins of filter feeding in lamniform sharks; that there is a single origin of filter feeding within Lamniformes, or conversely, the filter feeding adaptations have been developed independently due to different ancestral conditions. Evidence obtained from several studies strongly supports the latter hypothesis. Because evidence suggests that C. maximus and M. pelagios have developed their filter feeding adaptations independently, we expect to see convergent evolution taking place within these two lineages.