Convergent Evolution in Tooth Morphology of Filter Feeding Lamniform Sharks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Threshold Foraging Responses of Basking Sharks Be Used to Estimate Their Metabolic Rate?

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 200: 289-296,2000 Published July 14 Mar Ecol Prog Ser ~ NOTE Can threshold foraging responses of basking sharks be used to estimate their metabolic rate? David W. Sims* Department of Zoology, University of Aberdeen. Tillydrone Avenue. Aberdeen AB24 2TZ. United Kingdom ABSTRACT: Empirical and theoretical determinations of There are 3 species of filter-feeding shark, the whale minimum threshold prey densities for filter-feeding basking shark ~hi~~~d~~typus of warm-temperate and tropical sharks Cetorhinus maximus were used to test the idea that threshold foraging behaviour could provide a means for esti- seas worldwide, the basking shark Cetorhinus max- mating oxygen consumption (a proxy for metabolic rate). The im~~that inhabits warm-temperate to boreal waters threshold feeding levelrepres&nts the prey density at which circumglobally, and the megamouth shark Mega- there will be no net energy gain (energy intake equals expen- chasms pelagjos occurs in the Pacific and At- diture). Basking sharks were observed to cease feeding at lantic, primarily in deep water (Compagno 1984, Yano their theoretical threshold; thus, the assumption underpin- ning the concept presented here was that over the narrow et They are the largest marine verte- range of zooplankton prey densities that induce 'switching' brates attaining body lengths of up to 14, 10 and 6 m re- between feeding and non-feeding in basking sharks, the spectively. Comparatively little is known about the bi- energetic value of the minimum threshold prey density is ology of planktivorous sharks despite the fact that they equivalent to the shark's instantaneous level of energy expen- diture. -

An Introduction to the Classification of Elasmobranchs

An introduction to the classification of elasmobranchs 17 Rekha J. Nair and P.U Zacharia Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Introduction eyed, stomachless, deep-sea creatures that possess an upper jaw which is fused to its cranium (unlike in sharks). The term Elasmobranchs or chondrichthyans refers to the The great majority of the commercially important species of group of marine organisms with a skeleton made of cartilage. chondrichthyans are elasmobranchs. The latter are named They include sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. These for their plated gills which communicate to the exterior by organisms are characterised by and differ from their sister 5–7 openings. In total, there are about 869+ extant species group of bony fishes in the characteristics like cartilaginous of elasmobranchs, with about 400+ of those being sharks skeleton, absence of swim bladders and presence of five and the rest skates and rays. Taxonomy is also perhaps to seven pairs of naked gill slits that are not covered by an infamously known for its constant, yet essential, revisions operculum. The chondrichthyans which are placed in Class of the relationships and identity of different organisms. Elasmobranchii are grouped into two main subdivisions Classification of elasmobranchs certainly does not evade this Holocephalii (Chimaeras or ratfishes and elephant fishes) process, and species are sometimes lumped in with other with three families and approximately 37 species inhabiting species, or renamed, or assigned to different families and deep cool waters; and the Elasmobranchii, which is a large, other taxonomic groupings. It is certain, however, that such diverse group (sharks, skates and rays) with representatives revisions will clarify our view of the taxonomy and phylogeny in all types of environments, from fresh waters to the bottom (evolutionary relationships) of elasmobranchs, leading to a of marine trenches and from polar regions to warm tropical better understanding of how these creatures evolved. -

Lamna Nasus) Inferred from a Data Mining in the Spanish Longline Fishery Targeting Swordfish (Xiphias Gladius) in the Atlantic for the 1987-2017 Period

SCRS/2020/073 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 77(6): 89-117 (2020) SIZE AND AREA DISTRIBUTION OF PORBEAGLE (LAMNA NASUS) INFERRED FROM A DATA MINING IN THE SPANISH LONGLINE FISHERY TARGETING SWORDFISH (XIPHIAS GLADIUS) IN THE ATLANTIC FOR THE 1987-2017 PERIOD J. Mejuto1, A. Ramos-Cartelle1, B. García-Cortés1 and J. Fernández-Costa1 SUMMARY A total of 5,136 size observations of porbeagle were recovered for the period 1987-2017. The GLM results explained very moderately the variability of the sizes considering three main factors, suggesting minor but significant differences in some cases especially for the year factor and non-significant differences in other factors depending on the analysis. The greatest differences in the standardized mean length between some zones were caused by some large fish of unidentified sex. The standardized mean length data for the northern zones showed stability throughout the time series, very stable range of mean values and very few differences between sexes. The size distribution for northern areas indicated an FL-overall mean of 158 cm. The size showed a normal distribution confirming that a small fraction of individuals of this stock/s is available in the oceanic areas where the North Atlantic fleet is regularly fishing and the fishes are not fully recruited to those areas and / or this fishing gear up to 160 cm. The data suggests that some individuals could sporadically reach some intertropical areas of the eastern Atlantic. RÉSUMÉ Un total de 5.136 observations de taille de requins-taupes communs ont été récupérées pour la période 1987-2017. Les résultats du GLM expliquent très modérément la variabilité des tailles en tenant compte de trois facteurs principaux, ce qui suggère des différences mineures mais significatives dans certains cas, notamment pour le facteur année et des différences non significatives pour d'autres facteurs selon le type d’analyse. -

Electrosensory Pore Distribution and Feeding in the Basking Shark Cetorhinus Maximus (Lamniformes: Cetorhinidae)

Vol. 12: 33–36, 2011 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online March 3 doi: 10.3354/ab00328 Aquat Biol NOTE Electrosensory pore distribution and feeding in the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus (Lamniformes: Cetorhinidae) Ryan M. Kempster*, Shaun P. Collin The UWA Oceans Institute and the School of Animal Biology, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia ABSTRACT: The basking shark Cetorhinus maximus is the second largest fish in the world, attaining lengths of up to 10 m. Very little is known of its sensory biology, particularly in relation to its feeding behaviour. We describe the abundance and distribution of ampullary pores over the head and pro- pose that both the spacing and orientation of electrosensory pores enables C. maximus to use passive electroreception to track the diel vertical migrations of zooplankton that enable the shark to meet the energetic costs of ram filter feeding. KEY WORDS: Ampullae of Lorenzini · Electroreception · Filter feeding · Basking shark Resale or republication not permitted without written consent of the publisher INTRODUCTION shark Rhincodon typus and the megamouth shark Megachasma pelagios, which can attain lengths of up Electroreception is an ancient sensory modality that to 14 and 6 m, respectively (Compagno 1984). These 3 has evolved independently across the animal kingdom filter-feeding sharks are among the largest living in multiple groups (Scheich et al. 1986, Collin & White- marine vertebrates (Compagno 1984) and yet they are head 2004). Repeated independent evolution of elec- all able to meet their energetic costs through the con- troreception emphasises the importance of this sense sumption of tiny zooplankton. -

Order LAMNIFORMES ODONTASPIDIDAE Sand Tiger Sharks Iagnostic Characters: Large Sharks

click for previous page Lamniformes: Odontaspididae 419 Order LAMNIFORMES ODONTASPIDIDAE Sand tiger sharks iagnostic characters: Large sharks. Head with 5 medium-sized gill slits, all in front of pectoral-fin bases, Dtheir upper ends not extending onto dorsal surface of head; eyes small or moderately large, with- out nictitating eyelids; no nasal barbels or nasoral grooves; snout conical or moderately depressed, not blade-like;mouth very long and angular, extending well behind eyes when jaws are not protruded;lower labial furrows present at mouth corners; anterior teeth enlarged, with long, narrow, sharp-edged but unserrated cusps and small basal cusplets (absent in young of at least 1 species), the upper anteriors separated from the laterals by a gap and tiny intermediate teeth; gill arches without rakers; spiracles present but very small. Two moderately large high dorsal fins, the first dorsal fin originating well in advance of the pelvic fins, the second dorsal fin as large as or somewhat smaller than the first dorsal fin;anal fin as large as second dorsal fin or slightly smaller; caudal fin short, asymmetrical, with a strong subterminal notch and a short but well marked ventral lobe. Caudal peduncle not depressed, without keels; a deep upper precaudal pit present but no lower pit. Intestinal valve of ring type, with turns closely packed like a stack of washers. Colour: grey or grey-brown to blackish above, blackish to light grey or white, with round or oval dark spots and blotches vari- ably present on 2 species. high dorsal fins upper precaudal eyes without pit present nictitating eyelids intestinal valve of ring type Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Wide-ranging, tropical to cool-temperate sharks, found inshore and down to moderate depths on the edge of the continental shelves and around some oceanic islands, and in the open ocean. -

Population Structure and Biology of Shortfin Mako, Isurus Oxyrinchus, in the South-West Indian Ocean

CSIRO PUBLISHING Marine and Freshwater Research http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MF13341 Population structure and biology of shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus, in the south-west Indian Ocean J. C. GroeneveldA,E, G. Cliff B, S. F. J. DudleyC, A. J. FoulisA, J. SantosD and S. P. WintnerB AOceanographic Research Institute, PO Box 10712, Marine Parade 4056, Durban, South Africa. BKwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board, Private Bag 2, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, South Africa. CFisheries Management, Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Private Bag X2, Rogge Bay 8012, South Africa. DNorwegian College of Fishery Science, University of Tromsø, NO-9037, Tromsø, Norway. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The population structure, reproductive biology, age and growth, and diet of shortfin makos caught by pelagic longliners (2005–10) and bather protection nets (1978–2010) in the south-west Indian Ocean were investigated. The mean fork length (FL) of makos measured by observers on longliners targeting tuna, swordfish and sharks was similar, and decreased from east to west, with the smallest individuals occurring near the Agulhas Bank edge, June to November. Nearly all makos caught by longliners were immature, with equal sex ratio. Makos caught by bather protection nets were significantly larger, males were more frequent, and 93% of males and 55% of females were mature. Age was assessed from band counts of sectioned vertebrae, and a von Bertalanffy growth model fitted to sex-pooled length-at-age data predicted a À1 birth size (L0) of 90 cm, maximum FL (LN) of 285 cm and growth coefficient (k) of 0.113 y . -

Teeth Penetration Force of the Tiger Shark Galeocerdo Cuvier and Sandbar Shark Carcharhinus Plumbeus

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 91, 460–472 doi:10.1111/jfb.13351, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Teeth penetration force of the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus J. N. Bergman*†‡, M. J. Lajeunesse* and P. J. Motta* *University of South Florida, Department of Integrative Biology, 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL 33620, U.S.A. and †Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 100 Eighth Avenue S.E., Saint Petersburg, FL 33701, U.S.A. (Received 16 February 2017, Accepted 15 May 2017) This study examined the minimum force required of functional teeth and replacement teeth in the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and the sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus to penetrate the scales and muscle of sheepshead Archosargus probatocephalus and pigfish Orthopristis chrysoptera. Penetra- tion force ranged from 7·7–41·9and3·2–26·3 N to penetrate A. probatocephalus and O. chrysoptera, respectively. Replacement teeth required significantly less force to penetrate O. chrysoptera for both shark species, most probably due to microscopic wear of the tooth surfaces supporting the theory shark teeth are replaced regularly to ensure sharp teeth that are efficient for prey capture. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: biomechanics; bite force; Elasmobranchii; teleost; tooth morphology. INTRODUCTION Research on the functional morphology of feeding in sharks has typically focused on the kinematics and mechanics of cranial movement (Ferry-Graham, 1998; Wilga et al., 2001; Motta, 2004; Huber et al., 2005; Motta et al., 2008), often neglecting to integrate the function of teeth (but see Ramsay & Wilga, 2007; Dean et al., 2008; Whitenack et al., 2011). -

Can Sharks Be Saved? a Global Plan of Action for Shark Conservation in the Regime of the Convention on Migratory Species

Seattle Journal of Environmental Law Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 15 5-31-2015 Can Sharks be Saved? A Global Plan of Action for Shark Conservation in the Regime of the Convention on Migratory Species James Kraska Leo Chan Gaskins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjel Part of the Education Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Kraska, James and Gaskins, Leo Chan (2015) "Can Sharks be Saved? A Global Plan of Action for Shark Conservation in the Regime of the Convention on Migratory Species," Seattle Journal of Environmental Law: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 15. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjel/vol5/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal of Environmental Law by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. Can Sharks be Saved? A Global Plan of Action for Shark Conservation in the Regime of the Convention on Migratory Species James Kraska† and Leo Chan Gaskins‡ Shark populations throughout the world are at grave risk; some spe- cies have declined by 95 percent. The most recent IUCN (Interna- tional Union for the Conservation of Nature) assessment by the Shark Specialist Group (SSG) found that one-fourth of shark and ray spe- cies face the prospect of extinction. -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

State of Oregon The ORE BIN· Department of Geology Volume 34,no. 10 and Mineral Industries 1069 State Office BI dg. October 1972 Portland Oregon 97201 FOSSil SHARKS IN OREGON Bruce J. Welton* Approximately 21 species of sharks, skates, and rays are either indigenous to or occasionally visit the Oregon coast. The Blue Shark Prionace glauca, Soup-fin Shark Galeorhinus zyopterus, and the Dog-fish Shark Squalus acanthias commonly inhabit our coastal waters. These 21 species are represented by 16 genera, of which 10 genera are known from the fossi I record in Oregon. The most common genus encountered is the Dog-fish Shark Squalus. The sharks, skates, and rays, (all members of the Elasmobranchii) have a fossil record extending back into the Devonian period, but many major groups became extinct before or during the Mesozoic. A rapid expansion in the number of new forms before the close of the Mesozoic gave rise to practically all the Holocene families living today. Paleozoic shark remains are not known from Oregon, but teeth of the Cretaceous genus Scapanorhyn chus have been collected from the Hudspeth Formation near Mitchell, Oregon. Recent work has shown that elasmobranch teeth occur in abundance west of the Cascades in marine Tertiary strata ranging in age from late Eocene to middle Miocene (Figures 1 and 2). All members of the EIasmobranchii possess a cartilaginous endoskeleton which deteriorates rapidly upon death and is only rarely preserved in the fossil record. Only under exceptional conditions of preservation, usually in a highly reducing environment, will cranial or postcranial elements be fossilized. -

Juvenile Megamouth Shark, Megachasma Pelagios, Caught Off the Pacific Coast of Mexico, and Its Significance to Chondrichthyan Diversity in Mexico

Ciencias Marinas (2012), 38(2): 467–474 Research Note/Nota de Investigación C M Juvenile megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios, caught off the Pacific coast of Mexico, and its significance to chondrichthyan diversity in Mexico Tiburón bocudo juvenil, Megachasma pelagios, capturado en la costa del Pacífico de México, y su relevancia para la diversidad de los peces condrictios en México JL Castillo-Géniz1*, AI Ocampo-Torres2, K Shimada3, 4, CK Rigsby5, AC Nicholas5 1 Centro Regional de Investigación Pesquera de Ensenada, BC, Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Carr. Tijuana- Ensenada Km 97.5, El Sauzal de Rodríguez, CP 22760 Ensenada, Baja California, México. 2 Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Departamento de Oceanografía Física, Carr. Ensenada-Tijuana 3918, Zona Playitas, CP 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, México. 3 Department of Environmental Science and Studies and Department of Biological Sciences, DePaul University, 2325 North Clifton Avenue, Chicago, IL 60614, USA. 4 Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Fort Hays State University, 3000 Sternberg Drive, Hays, Kansas 67601, USA. 5 Department of Medical Imaging, Children’s Memorial Hospital, 2300 Children’s Plaza No. 9, Chicago, Illinois 60614, USA * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. On 16 November 2006, a female juvenile megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios, was caught off the coast of Mexico in the Pacific Ocean, near Sebastián Vizcaíno Bay. This specimen, that has informally been referred to as “Megamouth No. 38”, measured 2265 mm in total length. It represents the third smallest female recorded for this taxon and the first report of M. pelagios off the Pacific coast of Mexico. -

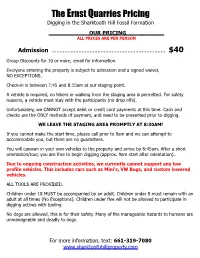

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation OUR PRICING ALL PRICES ARE PER PERSON Admission ........................................................................ $40 Group Discounts for 10 or more, email for information. Everyone entering the property is subject to admission and a signed waiver, NO EXCEPTIONS. Check-in is between 7:45 and 8:15am at our staging point. A vehicle is required, no hikers or walking from the staging area is permitted. For safety reasons, a vehicle must stay with the participants (no drop offs). Unfortunately, we CANNOT accept debit or credit card payments at this time. Cash and checks are the ONLY methods of payment, and need to be presented prior to digging. WE LEAVE THE STAGING AREA PROMPTLY AT 8:30AM! If you cannot make the start time, please call prior to 8am and we can attempt to accommodate you, but there are no guarantees. You will caravan in your own vehicles to the property and arrive by 8:45am. After a short orientation/tour, you are free to begin digging (approx. 9am start after orientation). Due to ongoing construction activities, we currently cannot support any low profile vehicles. This includes cars such as Mini's, VW Bugs, and custom lowered vehicles. ALL TOOLS ARE PROVIDED. Children under 18 MUST be accompanied by an adult. Children under 8 must remain with an adult at all times (No Exceptions). Children under five will not be allowed to participate in digging actives with tooling. No dogs are allowed, this is for their safety. Many of the manageable hazards to humans are unmanageable and deadly to dogs. -

FAU Institutional Repository This

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: ©1983 American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. This manuscript is an author version with the final publication available and may be cited as: Gilmore, R. G. (1983). Observations on the embryos of the longfin mako, Isurus paucus, and the bigeye thresher, Alopias superciliosus. Copeia 2, 375-382. /<""\ \ Copria, 1983(2), pp. 375-382 Observations on the Embryos of the Longfin Mako, Jsurus paucus, and the Bigeye Thresher, Alopias superciliosus R. GRANT GILMORE Four embryos of Alopias superciliosus and one of lsurus paucus were dissected and examined along with the reproductive organs of adults captured in the Florida Current off the east-central coast of Florida between latitude 26°30'N and 28°30'N. The embryos were found to contain yolk, demonstrating prenatal nutrition through intrauterine oophagy. Various proportions of embryo anatomy considered diagnostic for these species resemble those of adults. The general gonad morphology and presence of egg capsules containing multiple ova resem ble the described development stages of other lamnids, alopiids and Odontaspis taurus (Odontaspidae). This is the first documented observation of oophagy in these species. OPHAGOUS embryos have been record As these species are rarely caught and examined O ed in three elasmobranch families, Odon by biologists, there are no documented obser taspidae (Odontaspis taurus, Springer, 1948; Bass vations of oophagy in Alopias superciliosus and eta!., 1975; Pseudocarcharias kamoharai, Fujita, lsurus paucus. For this reason I present the fol 1 981 ), Lamnidae (Lamna nasus, Lohberger, lowing embryonic description of Isurus paucus 191 0; Shann, 1911, 1923; Bigelow and Schroe and Alopias superciliosus with evidence of oo der, 1948) and Alopiidae (Alopias vulpinus, Gub phagy in these species.