Lowery D., S. J. Godfrey, and R. Eshelman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of Carcharocles Megalodon in the Eastern

Estudios Geológicos julio-diciembre 2015, 71(2), e032 ISSN-L: 0367-0449 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/egeol.41828.342 Record of Carcharocles megalodon in the Eastern Guadalquivir Basin (Upper Miocene, South Spain) Registro de Carcharocles megalodon en el sector oriental de la Cuenca del Guadalquivir (Mioceno superior, Sur de España) M. Reolid, J.M. Molina Departamento de Geología, Universidad de Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas sn, 23071 Jaén, Spain. Email: [email protected] / [email protected] ABSTRACT Tortonian diatomites of the San Felix Quarry (Porcuna), in the Eastern Guadalquivir Basin, have given isolated marine vertebrate remains that include a large shark tooth (123.96 mm from apex to the baseline of the root). The large size of the crown height (92.2 mm), the triangular shape, the broad serrated crown, the convex lingual face and flat labial face, and the robust, thick angled root determine that this specimen corresponds to Carcharocles megalodon. The symmetry with low slant shows it to be an upper anterior tooth. The total length estimated from the tooth crown height is calculated by means of different methods, and comparison is made with Carcharodon carcharias. The final inferred total length of around 11 m classifies this specimen in the upper size range of the known C. megalodon specimens. The palaeogeography of the Guadalquivir Basin close to the North Betic Strait, which connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, favoured the interaction of the cold nutrient-rich Atlantic waters with warmer Mediterranean waters. The presence of diatomites indicates potential upwelling currents in this context, as well as high productivity favouring the presence of large vertebrates such as mysticetid whales, pinnipeds and small sharks (Isurus). -

First Description of a Tooth of the Extinct Giant Shark Carcharocles

First description of a tooth of the extinct giant shark Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835) found in the province of Seville (SW Iberian Peninsula) (Otodontidae) Primera descripción de un diente del extinto tiburón gigante Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835) encontrado en la provincia de Sevilla (SO de la Península Ibérica) (Otodontidae) José Luis Medina-Gavilán 1, Antonio Toscano 2, Fernando Muñiz 3, Francisco Javier Delgado 4 1. Sociedad de Estudios Ambientales (SOCEAMB) − Perú 4, 41100 Coria del Río, Sevilla (Spain) − [email protected] 2. Departamento de Geodinámica y Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales, Universidad de Huelva − Campus El Carmen, 21071 Huelva (Spain) − [email protected] 3. Departamento de Geodinámica y Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales, Universidad de Huelva − Campus El Carmen, 21071 Huelva (Spain) − [email protected] 4. Usuario de BiodiversidadVirtual.org − Álvarez Quintero 13, 41220 Burguillos, Sevilla (Spain) − [email protected] ABSTRACT: Fossil remains of the extinct giant shark Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835) are rare in interior Andalusia (Southern Spain). For the first time, a fossil tooth belonging to this paleospecies is described from material found in the province of Seville (Burguillos). KEY WORDS: Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835), megalodon, Otodontidae, fossil, paleontology, Burguillos, Seville, Tortonian. RESUMEN: Los restos del extinto tiburón gigante Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835) son raros en el interior de Andalucía (sur de España). Por primera vez, se describe un diente fósil de esta paleoespecie a partir de material hallado en Sevilla (Burguillos). PALABRAS CLAVE: Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835), megalodón, Otodontidae, fósil, paleontología, Burguillos, Sevilla, Tortoniense. Introduction Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1835), the megalodon, is widely recognised as the largest shark that ever lived. -

Teeth Penetration Force of the Tiger Shark Galeocerdo Cuvier and Sandbar Shark Carcharhinus Plumbeus

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 91, 460–472 doi:10.1111/jfb.13351, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Teeth penetration force of the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus J. N. Bergman*†‡, M. J. Lajeunesse* and P. J. Motta* *University of South Florida, Department of Integrative Biology, 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL 33620, U.S.A. and †Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 100 Eighth Avenue S.E., Saint Petersburg, FL 33701, U.S.A. (Received 16 February 2017, Accepted 15 May 2017) This study examined the minimum force required of functional teeth and replacement teeth in the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and the sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus to penetrate the scales and muscle of sheepshead Archosargus probatocephalus and pigfish Orthopristis chrysoptera. Penetra- tion force ranged from 7·7–41·9and3·2–26·3 N to penetrate A. probatocephalus and O. chrysoptera, respectively. Replacement teeth required significantly less force to penetrate O. chrysoptera for both shark species, most probably due to microscopic wear of the tooth surfaces supporting the theory shark teeth are replaced regularly to ensure sharp teeth that are efficient for prey capture. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: biomechanics; bite force; Elasmobranchii; teleost; tooth morphology. INTRODUCTION Research on the functional morphology of feeding in sharks has typically focused on the kinematics and mechanics of cranial movement (Ferry-Graham, 1998; Wilga et al., 2001; Motta, 2004; Huber et al., 2005; Motta et al., 2008), often neglecting to integrate the function of teeth (but see Ramsay & Wilga, 2007; Dean et al., 2008; Whitenack et al., 2011). -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

State of Oregon The ORE BIN· Department of Geology Volume 34,no. 10 and Mineral Industries 1069 State Office BI dg. October 1972 Portland Oregon 97201 FOSSil SHARKS IN OREGON Bruce J. Welton* Approximately 21 species of sharks, skates, and rays are either indigenous to or occasionally visit the Oregon coast. The Blue Shark Prionace glauca, Soup-fin Shark Galeorhinus zyopterus, and the Dog-fish Shark Squalus acanthias commonly inhabit our coastal waters. These 21 species are represented by 16 genera, of which 10 genera are known from the fossi I record in Oregon. The most common genus encountered is the Dog-fish Shark Squalus. The sharks, skates, and rays, (all members of the Elasmobranchii) have a fossil record extending back into the Devonian period, but many major groups became extinct before or during the Mesozoic. A rapid expansion in the number of new forms before the close of the Mesozoic gave rise to practically all the Holocene families living today. Paleozoic shark remains are not known from Oregon, but teeth of the Cretaceous genus Scapanorhyn chus have been collected from the Hudspeth Formation near Mitchell, Oregon. Recent work has shown that elasmobranch teeth occur in abundance west of the Cascades in marine Tertiary strata ranging in age from late Eocene to middle Miocene (Figures 1 and 2). All members of the EIasmobranchii possess a cartilaginous endoskeleton which deteriorates rapidly upon death and is only rarely preserved in the fossil record. Only under exceptional conditions of preservation, usually in a highly reducing environment, will cranial or postcranial elements be fossilized. -

Ancient Carpet Shark Discovered with 'Spaceship-Shaped' Teeth 21 January 2019

Ancient carpet shark discovered with 'spaceship-shaped' teeth 21 January 2019 ago, what is now South Dakota was covered in forests, swamps and winding rivers," Gates says. "Galagadon was not swooping in to prey on T. rex, Triceratops, or any other dinosaurs that happened into its streams. This shark had teeth that were good for catching small fish or crushing snails and crawdads." Galagadon. Credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum The world of the dinosaurs just got a bit more bizarre with a newly discovered species of freshwater shark whose tiny teeth resemble the alien ships from the popular 1980s video game Galaga. Unlike its gargantuan cousin the megalodon, Galagadon nordquistae was a small shark (approximately 12 to 18 inches long), related to modern-day carpet sharks such as the "whiskered" wobbegong. Galagadon once swam in the Cretaceous rivers of what is now South Dakota, and its remains were uncovered beside "Sue," the world's most famous T. rex fossil. Galagadon teeth. Credit: Terry Gates, NC State University "The more we discover about the Cretaceous period just before the non-bird dinosaurs went extinct, the more fantastic that world becomes," says Terry Gates, lecturer at North Carolina State The tiny teeth – each one measuring less than a University and research affiliate with the North millimeter across – were discovered in the sediment Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Gates is left behind when paleontologists at the Field lead author of a paper describing the new species Museum uncovered the bones of "Sue," currently along with colleagues Eric Gorscak and Peter J. the most complete T. -

A Partial Rostrum of the Porbeagle Shark

GEOLOGICA BELGICA (2010) 13/1-2: 61-76 A PARTIAL ROSTRUM OF THE PORBEAGLE SHARK LAMNA NASUS (LAMNIFORMES, LAMNIDAE) FROM THE MIOCENE OF THE NORTH SEA BASIN AND THE TAXONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF ROSTRAL MORPHOLOGY IN EXTINCT SHARKS Frederik H. MOLLEN (4 figures, 3 plates) Elasmobranch Research, Meistraat 16, B-2590 Berlaar, Belgium; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. A fragmentary rostrum of a lamnid shark is recorded from the upper Miocene Breda Formation at Liessel (Noord-Brabant, The Netherlands); it constitutes the first elasmobranch rostral process to be described from Neogene strata in the North Sea Basin. Based on key features of extant lamniform rostra and CT scans of chondrocrania of modern Lamnidae, the Liessel specimen is assigned to the porbeagle shark, Lamna nasus (Bonnaterre, 1788). In addition, the taxonomic significance of rostral morphology in extinct sharks is discussed and a preliminary list of elasmobranch taxa from Liessel is presented. KEYWORDS. Lamniformes, Lamnidae, Lamna, rostrum, shark, rostral node, rostral cartilages, CT scans. 1. Introduction Pliocene) of North Carolina (USA), detailed descriptions and discussions were not presented, unfortunately. Only In general, chondrichthyan fish fossilise only under recently has Jerve (2006) reported on an ongoing study of exceptional conditions and (partial) skeletons of especially two Miocene otic capsules from the Calvert Formation large species are extremely rare (Cappetta, 1987). (lower-middle Miocene) of Maryland (USA); this will Therefore, the fossil record of Lamniformes primarily yield additional data to the often ambiguous dental studies. comprises only teeth (see e.g. Agassiz, 1833-1844; These well-preserved cranial structures were stated to be Leriche, 1902, 1905, 1910, 1926), which occasionally are homologous to those seen in extant lamnids and thus available as artificial, associated or natural tooth sets useful for future phylogenetic studies of this group. -

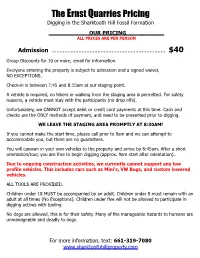

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation OUR PRICING ALL PRICES ARE PER PERSON Admission ........................................................................ $40 Group Discounts for 10 or more, email for information. Everyone entering the property is subject to admission and a signed waiver, NO EXCEPTIONS. Check-in is between 7:45 and 8:15am at our staging point. A vehicle is required, no hikers or walking from the staging area is permitted. For safety reasons, a vehicle must stay with the participants (no drop offs). Unfortunately, we CANNOT accept debit or credit card payments at this time. Cash and checks are the ONLY methods of payment, and need to be presented prior to digging. WE LEAVE THE STAGING AREA PROMPTLY AT 8:30AM! If you cannot make the start time, please call prior to 8am and we can attempt to accommodate you, but there are no guarantees. You will caravan in your own vehicles to the property and arrive by 8:45am. After a short orientation/tour, you are free to begin digging (approx. 9am start after orientation). Due to ongoing construction activities, we currently cannot support any low profile vehicles. This includes cars such as Mini's, VW Bugs, and custom lowered vehicles. ALL TOOLS ARE PROVIDED. Children under 18 MUST be accompanied by an adult. Children under 8 must remain with an adult at all times (No Exceptions). Children under five will not be allowed to participate in digging actives with tooling. No dogs are allowed, this is for their safety. Many of the manageable hazards to humans are unmanageable and deadly to dogs. -

Reading Handout: How Megalodon Worked

Reading Handout: How Megalodon Worked Carcharodon megalodon, the megatooth shark, isn't just a favorite topic among science fiction fans and cryptozoologists (who study evidence of the existence of unverified species) -- it was a real, living shark that roamed the oceans around 1.5 to 20 million years ago. Carcharodon megalodon was discovered in the 1600s when naturalist Nicolaus Steno identified large fossils -- previously thought to be tongues of dragons or snakes -- as giant shark teeth. Since then, biologists and scientists have unearthed hundreds of fossilized megalodon teeth and centra (boney, vertebrae-like spinal segments), allowing us to learn more about this mysterious creature of the ancient seas. Mega Anatomy Since the skeleton of a shark is primarily made up of cartilage, which decomposes over time, the only megalodon remains we've discovered are serrated teeth and vertebrae- like centra. This has left experts with the arduous task of reconstructing megalodon's anatomy based on limited knowledge. But, just as human dental records can be examined postmortem to identify remains, shark teeth can also tell experts enough to identify the species and its size, possible prey, and prey size. Hundreds of megalodon tooth fossils have been found, and they average 6 inches in length -- about the size of a human hand. By comparison, great white sharks' teeth average around 2 inches long. Using fossilized teeth, scientists have reconstructed the jaws of the megalodon and discovered that this shark's mouth was a staggering 7 feet in diameter. Based on this reconstruction and additional research, experts believe that this ancient shark had a broad, domed head with a short snout and massive jaws. -

Re-Evaluation of Pachycormid Fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany

Editors' choice Re-evaluation of pachycormid fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany ERIN E. MAXWELL, PAUL H. LAMBERS, ADRIANA LÓPEZ-ARBARELLO, and GÜNTER SCHWEIGERT Maxwell, E.E., Lambers, P.H., López-Arbarello, A., and Schweigert G. 2020. Re-evaluation of pachycormid fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 65 (3): 429–453. Pachycormidae is an extinct group of Mesozoic fishes that exhibits extensive body size and shape disparity. The Late Jurassic record of the group is dominated by fossils from the lithographic limestone of Bavaria, Germany that, although complete and articulated, are not well characterized anatomically. In addition, stratigraphic and geographical provenance are often only approximately known, making these taxa difficult to place in a global biogeographical context. In contrast, the late Kimmeridgian Nusplingen Plattenkalk of Baden-Württemberg is a well-constrained locality yielding hundreds of exceptionally preserved and prepared vertebrate fossils. Pachycormid fishes are rare, but these finds have the potential to broaden our understanding of anatomical variation within this group, as well as provide new information regarding the trophic complexity of the Nusplingen lagoonal ecosystem. Here, we review the fossil record of Pachycormidae from Nusplingen, including one fragmentary and two relatively complete skulls, a largely complete fish, and a fragment of a caudal fin. These finds can be referred to three taxa: Orthocormus sp., Hypsocormus posterodorsalis sp. nov., and Simocormus macrolepidotus gen. et sp. nov. The latter taxon was erected to replace “Hypsocormus” macrodon, here considered to be a nomen dubium. Hypsocormus posterodorsalis is known only from Nusplingen, and is characterized by teeth lacking apicobasal ridging at the bases, a dorsal fin positioned opposite the anterior edge of the anal fin, and a hypural plate consisting of a fused parhypural and hypurals. -

Body Length Estimation of Neogene Macrophagous Lamniform Sharks (Carcharodon and Otodus) Derived from Associated Fossil Dentitions

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Body length estimation of Neogene macrophagous lamniform sharks (Carcharodon and Otodus) derived from associated fossil dentitions Victor J. Perez, Ronny M. Leder, and Teddy Badaut ABSTRACT The megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon, is widely accepted as the largest mac- rophagous shark that ever lived; and yet, despite over a century of research, its size is still debated. The great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, is regarded as the best living ecological analog to the extinct megatooth shark and has been the basis for all body length estimates to date. The most widely accepted and applied method for esti- mating body size of O. megalodon was based upon a linear relationship between tooth crown height and total body length in C. carcharias. However, when applying this method to an associated dentition of O. megalodon (UF-VP-311000), the estimates for this single individual ranged from 11.4 to 41.1 m. These widely variable estimates showed a distinct pattern, in which anterior teeth resulted in lower estimates than pos- terior teeth. Consequently, previous paleoecological analyses based on body size esti- mates of O. megalodon may be subject to misinterpretation. Herein, we describe a novel method based on the summed crown width of associated fossil dentitions, which mitigates the variability associated with different tooth positions. The method assumes direct proportionality between the ratio of summed crown width to body length in eco- logically and taxonomically related fossil and modern species. Total body lengths were estimated from 11 individuals, representing five lamniform species: Otodus megal- odon, Otodus chubutensis, Carcharodon carcharias, Carcharodon hubbelli, and Carcharodon hastalis. -

Color and Learn: Sharks of Massachusetts!

COLOR AND LEARN: SHARKS OF MASSACHUSETTS! This book belongs to: WHAT IS A SHARK? Sharks are fish that have vertebrae (skeletons) made ofcartilage instead of bones. Sharks come in all different shapes, sizes, and colors. Sharks have different kinds of teeth, feeding patterns, swimming styles, and behaviors that help them to survive in all different kinds of aquatic habitats! Can you label the different parts of a shark? second dorsal fin caudal (tail) fin pelvic fin gills anal fin pectoral fin nostril mouth eye Dorsal fin There are around 500 species of sharks in the world. Massachusetts coastal waters provide ideal habitat for several kinds of Atlantic Ocean sharks that visit our waters each season! Massachusetts HOW LONG HAVE SHARKS BEEN ON EARTH? Sharks have been on Earth since before the dinosaurs! Scientists learn about early sharks by studying fossils. Shark fossils can tell us a lot about what food the shark ate, what their habitat looked like, and how they are related to other sharks. The ancient sharks on this page are extinct. Acanthodes (ah-can-tho-deez), or “spiny shark,” was the first fish to have a cartilage skeleton! Cladoselache (clay-do-sel-ah-kee) had a body and tail shaped for swimming fast. It did not have the same kind of skin that we see in modern sharks today. Stethacanthus (stef-ah-can-thus), or “anvil shark”, had a dorsal fin shaped like an ironing board! 450 370 360 200 145 60 6.5 MILLIONS OF YEARS AGO DINOSAURS EVOLVE WHAT ARE “MODERN” SHARKS? “Modern” sharks are species that have body parts (both inside and out!) that can be found on sharks living today. -

The Truth About Sharks the Story of the Sea Turtle the World of Whales

The Truth About Sharks Sharks are magnificent, but misunderstood creatures that are unfortunately being pushed to the brink of extinction due to overfishing and poor international management. This program highlights the beauty and importance of these animals by showing the incredible rich diversity of shark species and their unique adaptations. Students will rotate through hands-on stations in small groups that involve shark tooth and jaw morphology, shark identification, and shark sensory systems. The session culminates in a discussion about the critical need for conservation of many shark species and what students, no matter where they live, can do to help. The Story of the Sea Turtle Sea turtles are one of the most ancient creatures on Earth, yet we are still learning more and more about them every day. This program covers the life history, ecology, behavior, and unique adaptations of these extraordinary marine animals. Hands-on activities will highlight nesting behavior, sea turtle predators, how hatchings make it to the ocean, and how they are able to return to the same nesting beaches as adults. Students will have sea turtle models to study and even get a chance to experience what it is like for a sea turtle biologist studying these animals in the wild. The session ends in a discussion on current sea turtle conservation measures and how students can help protect marine life. The World of Whales Whales are found in every ocean region and are the largest mammals on the planet, yet we still have much to learn about these magnificent creatures. This program highlights the rich diversity of whale species and their unique adaptations that allow them to grow to mind-boggling dimensions, dive deep underwater, survive in cold-water habitats, and even sing elaborate songs to each other! Through hands-on activities, students will learn about whale feeding and communication strategies, and how scientists study these incredible animals in the wild.