Managing Sustainable Shark Fishing in the Mariana Archipelago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shark Cartilage, Cancer and the Growing Threat of Pseudoscience

[CANCER RESEARCH 64, 8485–8491, December 1, 2004] Review Shark Cartilage, Cancer and the Growing Threat of Pseudoscience Gary K. Ostrander,1 Keith C. Cheng,2 Jeffrey C. Wolf,3 and Marilyn J. Wolfe3 1Department of Biology and Department of Comparative Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; 2Jake Gittlen Cancer Research Institute, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania; and 3Registry of Tumors in Lower Animals, Experimental Pathology Laboratories, Inc., Sterling, Virginia Abstract primary justification for using crude shark cartilage extracts to treat cancer is based on the misconception that sharks do not, or infre- The promotion of crude shark cartilage extracts as a cure for cancer quently, develop cancer. Other justifications represent overextensions has contributed to at least two significant negative outcomes: a dramatic of experimental observations: concentrated extracts of cartilage can decline in shark populations and a diversion of patients from effective cancer treatments. An alleged lack of cancer in sharks constitutes a key inhibit tumor vessel formation and tumor invasions (e.g., refs. 2–5). justification for its use. Herein, both malignant and benign neoplasms of No available data or arguments support the medicinal use of crude sharks and their relatives are described, including previously unreported shark extracts to treat cancer (6). cases from the Registry of Tumors in Lower Animals, and two sharks with The claims that sharks do not, or rarely, get cancer was originally two cancers each. Additional justifications for using shark cartilage are argued by I. William Lane in a book entitled “Sharks Don’t Get illogical extensions of the finding of antiangiogenic and anti-invasive Cancer” in 1992 (7), publicized in “60 Minutes” television segments substances in cartilage. -

An Introduction to the Classification of Elasmobranchs

An introduction to the classification of elasmobranchs 17 Rekha J. Nair and P.U Zacharia Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Introduction eyed, stomachless, deep-sea creatures that possess an upper jaw which is fused to its cranium (unlike in sharks). The term Elasmobranchs or chondrichthyans refers to the The great majority of the commercially important species of group of marine organisms with a skeleton made of cartilage. chondrichthyans are elasmobranchs. The latter are named They include sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. These for their plated gills which communicate to the exterior by organisms are characterised by and differ from their sister 5–7 openings. In total, there are about 869+ extant species group of bony fishes in the characteristics like cartilaginous of elasmobranchs, with about 400+ of those being sharks skeleton, absence of swim bladders and presence of five and the rest skates and rays. Taxonomy is also perhaps to seven pairs of naked gill slits that are not covered by an infamously known for its constant, yet essential, revisions operculum. The chondrichthyans which are placed in Class of the relationships and identity of different organisms. Elasmobranchii are grouped into two main subdivisions Classification of elasmobranchs certainly does not evade this Holocephalii (Chimaeras or ratfishes and elephant fishes) process, and species are sometimes lumped in with other with three families and approximately 37 species inhabiting species, or renamed, or assigned to different families and deep cool waters; and the Elasmobranchii, which is a large, other taxonomic groupings. It is certain, however, that such diverse group (sharks, skates and rays) with representatives revisions will clarify our view of the taxonomy and phylogeny in all types of environments, from fresh waters to the bottom (evolutionary relationships) of elasmobranchs, leading to a of marine trenches and from polar regions to warm tropical better understanding of how these creatures evolved. -

Best Practice in the Prevention of Shark Finning

Best practice in the prevention of shark finning Brautigam, A. 2020. Best Practice in the Prevention of Shark Finning. Published by the Marine Stewardship Council [www.msc.org]. This work is licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0 to view a copy of this license, visit (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Marine Stewardship Council. Best Practice in the Prevention of Shark Finning FINAL Report to the Marine Stewardship Council Amie Bräutigam, Consultant 7 July 2020 Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Best Practice in the Prevent of Shark Finning FINAL Report – 7 July 2020 Table of Contents Acronyms, Abbreviations and Glossary of Terms ............................................................................................... .2 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Best Practice in the Prevention of Shark Finning – Scope and Methods.....……………………………………………...3 A. Scope…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..3 B. Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 III. Findings……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 A. Prevalence and Evolution of Fins Naturally Attached (FNA) Globally………………………………………..………..5 C. Taxonomic Coverage of Shark Finning Bans and FNA Requirements .................................................... -

Teeth Penetration Force of the Tiger Shark Galeocerdo Cuvier and Sandbar Shark Carcharhinus Plumbeus

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 91, 460–472 doi:10.1111/jfb.13351, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Teeth penetration force of the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus J. N. Bergman*†‡, M. J. Lajeunesse* and P. J. Motta* *University of South Florida, Department of Integrative Biology, 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL 33620, U.S.A. and †Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 100 Eighth Avenue S.E., Saint Petersburg, FL 33701, U.S.A. (Received 16 February 2017, Accepted 15 May 2017) This study examined the minimum force required of functional teeth and replacement teeth in the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier and the sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus to penetrate the scales and muscle of sheepshead Archosargus probatocephalus and pigfish Orthopristis chrysoptera. Penetra- tion force ranged from 7·7–41·9and3·2–26·3 N to penetrate A. probatocephalus and O. chrysoptera, respectively. Replacement teeth required significantly less force to penetrate O. chrysoptera for both shark species, most probably due to microscopic wear of the tooth surfaces supporting the theory shark teeth are replaced regularly to ensure sharp teeth that are efficient for prey capture. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: biomechanics; bite force; Elasmobranchii; teleost; tooth morphology. INTRODUCTION Research on the functional morphology of feeding in sharks has typically focused on the kinematics and mechanics of cranial movement (Ferry-Graham, 1998; Wilga et al., 2001; Motta, 2004; Huber et al., 2005; Motta et al., 2008), often neglecting to integrate the function of teeth (but see Ramsay & Wilga, 2007; Dean et al., 2008; Whitenack et al., 2011). -

Fishing for Sharks History of Shark Finning Protection Towards Sharks Importance of Sharks Sharks Are a Top Predator of the Ocean

Shark Finning Tiana Barron-Wright Fishing for Sharks History of Shark Finning Protection Towards Sharks Importance of Sharks Sharks are a top predator of the ocean. However, sharks are a target Shark fin soup originated in 968 AD by an emperor from the Sung The Shark Finning Prohibition Act of 2000, was signed by former Sharks play an important role in the ecosystem. Sharks maintain the for humans. Shark finning is the process of cutting off a shark’s Dynasty. The emperor created shark fin soup to display his wealth, President Bill Clinton. This act prohibited the process of shark finning in species below them in the ecosystem and serve as a health indicator for the fins while it is still alive and throwing the shark back into the power and generosity towards his guest. Serving shark fin soup the United States. This bans anyone in the United States jurisdiction from ocean. The decrease of sharks in the oceans has led to the decline of coral ocean where it will die. After getting their fins cut off, some sharks shark finning, owning shark fins without the shark’s body, and landing reefs, sea grass beds, and the loss of commercial fisheries. Without sharks was seen as a show of respect. Chinese Emperors thought the dish in the ecosystem, other predators can thrive. For example, groupers can can starve to death, get eaten by other fish or drown to death. shark fins without the body. This act also has NOAA (National Oceanic had medicinal benefits. Shark fin soup is considered a delicacy in and Atmospheric Administration) Fisheries to give Congress a report increase in numbers and eat herbivores. -

What Is Shark Finning and Why Is It Harmful?

What is shark finning and why is it harmful? Shark finning is defined as the onboard removal of a shark’s fins and the discarding of the body at sea. This practice poses a significant threat to many shark stocks and to the health of marine ecosystems. It is also a threat to traditional fisheries and to food security in some low-income countries. A threat to sharks Tens of millions of sharks are finned every year. Once the shark has been discarded, the fins can be dried on deck, eliminating the need for freezer space. It is therefore inherently unsustainable, since it allows fishers to catch an almost unlimited number of sharks. This greatly increases the threat to sharks and, by removing large numbers of top predators from marine ecosystems, is likely to have dramatic and negative impacts on other species, including commercially-important species. Predictive modelling has shown that the removal of sharks from their ecosystems can have unpredictable and often devastating impacts on other species. Sharks are highly vulnerable to over-exploitation, owing to their slow growth, long gestation and low reproductive output. Over-exploited shark stocks can take years or even decades to recover. Some European shark fisheries that were closed fifty years ago remain so, as the populations have yet to recover. The threat of over-exploitation is exacerbated by the lengthy migrations undertaken by many shark species. Even if they are protected in one area, sharks can move into areas where they are not subject to protection. A threat to shark management Gathering and analysing catch data is the sine qua non of shark conservation. -

Sharks in the Seas Around Us: How the Sea Around Us Project Is Working to Shape Our Collective Understanding of Global Shark Fisheries

Sharks in the seas around us: How the Sea Around Us Project is working to shape our collective understanding of global shark fisheries Leah Biery1*, Maria Lourdes D. Palomares1, Lyne Morissette2, William Cheung1, Reg Watson1, Sarah Harper1, Jennifer Jacquet1, Dirk Zeller1, Daniel Pauly1 1Sea Around Us Project, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada 2UNESCO Chair in Integrated Analysis of Marine Systems. Université du Québec à Rimouski, Institut des sciences de la mer; 310, Allée des Ursulines, C.P. 3300, Rimouski, QC, G5L 3A1, Canada Report prepared for The Pew Charitable Trusts by the Sea Around Us project December 9, 2011 *Corresponding author: [email protected] Sharks in the seas around us Table of Contents FOREWORD........................................................................................................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 SHARK BIODIVERSITY IS THREATENED ............................................................................. 10 SHARK-RELATED LEGISLATION ............................................................................................. 13 SHARK FIN TO BODY WEIGHT RATIOS ................................................................................ 14 -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

State of Oregon The ORE BIN· Department of Geology Volume 34,no. 10 and Mineral Industries 1069 State Office BI dg. October 1972 Portland Oregon 97201 FOSSil SHARKS IN OREGON Bruce J. Welton* Approximately 21 species of sharks, skates, and rays are either indigenous to or occasionally visit the Oregon coast. The Blue Shark Prionace glauca, Soup-fin Shark Galeorhinus zyopterus, and the Dog-fish Shark Squalus acanthias commonly inhabit our coastal waters. These 21 species are represented by 16 genera, of which 10 genera are known from the fossi I record in Oregon. The most common genus encountered is the Dog-fish Shark Squalus. The sharks, skates, and rays, (all members of the Elasmobranchii) have a fossil record extending back into the Devonian period, but many major groups became extinct before or during the Mesozoic. A rapid expansion in the number of new forms before the close of the Mesozoic gave rise to practically all the Holocene families living today. Paleozoic shark remains are not known from Oregon, but teeth of the Cretaceous genus Scapanorhyn chus have been collected from the Hudspeth Formation near Mitchell, Oregon. Recent work has shown that elasmobranch teeth occur in abundance west of the Cascades in marine Tertiary strata ranging in age from late Eocene to middle Miocene (Figures 1 and 2). All members of the EIasmobranchii possess a cartilaginous endoskeleton which deteriorates rapidly upon death and is only rarely preserved in the fossil record. Only under exceptional conditions of preservation, usually in a highly reducing environment, will cranial or postcranial elements be fossilized. -

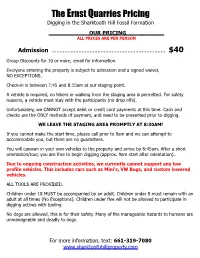

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation

The Ernst Quarries Pricing Digging in the Sharktooth Hill Fossil Formation OUR PRICING ALL PRICES ARE PER PERSON Admission ........................................................................ $40 Group Discounts for 10 or more, email for information. Everyone entering the property is subject to admission and a signed waiver, NO EXCEPTIONS. Check-in is between 7:45 and 8:15am at our staging point. A vehicle is required, no hikers or walking from the staging area is permitted. For safety reasons, a vehicle must stay with the participants (no drop offs). Unfortunately, we CANNOT accept debit or credit card payments at this time. Cash and checks are the ONLY methods of payment, and need to be presented prior to digging. WE LEAVE THE STAGING AREA PROMPTLY AT 8:30AM! If you cannot make the start time, please call prior to 8am and we can attempt to accommodate you, but there are no guarantees. You will caravan in your own vehicles to the property and arrive by 8:45am. After a short orientation/tour, you are free to begin digging (approx. 9am start after orientation). Due to ongoing construction activities, we currently cannot support any low profile vehicles. This includes cars such as Mini's, VW Bugs, and custom lowered vehicles. ALL TOOLS ARE PROVIDED. Children under 18 MUST be accompanied by an adult. Children under 8 must remain with an adult at all times (No Exceptions). Children under five will not be allowed to participate in digging actives with tooling. No dogs are allowed, this is for their safety. Many of the manageable hazards to humans are unmanageable and deadly to dogs. -

Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997

The IUCN Species Survival Commission Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 Edited by Sarah L. Fowler, Tim M. Reed and Frances A. Dipper Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 25 IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 The IUCN/Species Survival Commission is committed to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC's Wildlife Trade Programme and Conservation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conservation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts as well as promotion of conservation education, research and international cooperation. -

Shark Fishing and the Fin Trade in Ghana: a Biting Review

Plenty of Fish in the Sea? Shark Fishing and the Fin Trade in Ghana: A Biting Review Max J. Gelber A Field Practicum Report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Sustainable Development Practice Degree at the University of Florida, in Gainesville, FL USA May 2018 Supervisory Committee: Dr. Paul Monaghan, Chair Dr. Renata Serra, Member Men hauling in their shark catch in Shama, Ghana. (Author’s photo, 2017) Acknowledgements This project was supported through generous funding from UF’s Center for African Studies, Center for Latin American Studies, and Master of Sustainable Development Practice (MDP) program. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Paul Monaghan and Dr. Renata Serra, and the MDP program’s administration, Dr. Glenn Galloway and Dr. Andrew Noss, for their invaluable guidance and support over the past two years. Through thick and thin, these professors have remained by my side, encouraging me to continue to achieve as a lifelong learner; for this, I am forever gracious. I would also like to thank Mr. Samuel Kofi Darkwa (Ph.D student in Political Science at West Virginia University), my language instructor at the 2016 African Flagship Languages Initiative (AFLI) Domestic Intensive Summer Program at UF, and Mr. Mohammed Kofi Mustapha (Ph.D student in Anthropology at the UF), for teaching me Akan/Twi. Their dedication and support have been instrumental in the planning and execution of this project. I believe that the study of language serves as the premier gateway to better understanding people and culture, and my experience learning Akan/Twi has reinforced this belief in so many ways. -

Re-Evaluation of Pachycormid Fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany

Editors' choice Re-evaluation of pachycormid fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany ERIN E. MAXWELL, PAUL H. LAMBERS, ADRIANA LÓPEZ-ARBARELLO, and GÜNTER SCHWEIGERT Maxwell, E.E., Lambers, P.H., López-Arbarello, A., and Schweigert G. 2020. Re-evaluation of pachycormid fishes from the Late Jurassic of Southwestern Germany. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 65 (3): 429–453. Pachycormidae is an extinct group of Mesozoic fishes that exhibits extensive body size and shape disparity. The Late Jurassic record of the group is dominated by fossils from the lithographic limestone of Bavaria, Germany that, although complete and articulated, are not well characterized anatomically. In addition, stratigraphic and geographical provenance are often only approximately known, making these taxa difficult to place in a global biogeographical context. In contrast, the late Kimmeridgian Nusplingen Plattenkalk of Baden-Württemberg is a well-constrained locality yielding hundreds of exceptionally preserved and prepared vertebrate fossils. Pachycormid fishes are rare, but these finds have the potential to broaden our understanding of anatomical variation within this group, as well as provide new information regarding the trophic complexity of the Nusplingen lagoonal ecosystem. Here, we review the fossil record of Pachycormidae from Nusplingen, including one fragmentary and two relatively complete skulls, a largely complete fish, and a fragment of a caudal fin. These finds can be referred to three taxa: Orthocormus sp., Hypsocormus posterodorsalis sp. nov., and Simocormus macrolepidotus gen. et sp. nov. The latter taxon was erected to replace “Hypsocormus” macrodon, here considered to be a nomen dubium. Hypsocormus posterodorsalis is known only from Nusplingen, and is characterized by teeth lacking apicobasal ridging at the bases, a dorsal fin positioned opposite the anterior edge of the anal fin, and a hypural plate consisting of a fused parhypural and hypurals.