Mauritania Monthly Report for January 2002 Rapport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Formulation of Action Plan and Model for Gorgol Region

The Development Study for the Project on Revitalization of Irrigated Agriculture in the Irrigated Zone of Foum Gleita in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania Main Report CHAPTER 5 FORMULATION OF ACTION PLAN AND MODEL FOR GORGOL REGION 5.1 Issues of the Foum Gleita Project Area 5.1.1 Analysis of the History of the Foum Gleita Project The important events in Foum Gleita are reviewed to define the background of problems. However, the operation for the entire area has started about 20 years ago in 1990, and hence SONADER no longer possessed the documents of this period, and neither did the farmers. The information was fragmentary, and often the time of the events was not well defined and the description given by the farmers was different from each other. These issues were complicated, and it was difficult to ascertain the veracity of the facts. Based on these conditions, the Fig. 5.1.1 was prepared, and the chronological table on the left shows important events related to Foum Gleita and the figure on the right shows an image between necessary inputs for irrigated agriculture and cropping areas as its results. Actually, the problems of Foum Gleita were attributed to the fact that the scope of management and maintenance for mid and long term was not sufficient, and the farmers and the government did not play their roles. Then the problems were accumulated, while both of them do nothing. The figure 5.1.1 shows the real situation of Foum Gleita (left in red) and the idealistic responsibility and results (right in blue). -

Pdf | 94.29 Kb

ALERT LEVEL: MAURITANIA NO ALERT Monthly Food Security Update WATCH WARNING December 2006 EMERGENCY Conditions are normal, with pockets of food insecurity CONTENT Summary and implications Summary and implications ....1 As the last late-planted rain fed sorghum crops are harvested, cereal yield estimates indicate a Current hazards summary.....1 decrease from last year due to this year’s shorter than usual rainy season and damages from grain- Status of crops ......................1 eating birds during the heading stage of their growing cycle. Rice harvests are still in progress and Conditions in stock-raising most flood-recession crops have been planted. However, farmers did not plant flood recession crops areas .....................................2 in many areas of Gorgol region, due to fear of infestations of pink stalk borers, straying animals and Locust situation .....................2 pressure from grain-eating birds. While the locust situation remains calm, heavy pressure on off- season crops from grain-eating birds continue, despite large-scale control programs. Food security.........................2 Recommendations ................2 Conditions in the pastoral areas of central Mauritania (northern Brakna, northern Gorgol, central Trarza and Assaba) are beginning to deteriorate as a result of overgrazing and wind erosion. The pace of seasonal migration has picked up as herders and their animals search for better grazing lands and move closer to buyers in anticipation of the approaching Tabaski holiday (the Muslim Feast of Sacrifice). Supplies of sorghum and millet on grain markets remain limited, due largely to the shortfall in local production and the small volume of grain trade with Senegal. Transfers of Malian grain (from the 2004 and 2005 harvests) are picking up in border areas in the Southeast and in Nouakchott, keeping sorghum prices relatively stable, though prices on rural markets are trending upwards. -

Wvi Mauritania

MAURITANIA ZRB 510 – TVZ Nouakchott – BP 335 Tel : +222 45 25 3055 Fax : +222 45 25 118 www.wvi.org/mauritania PHOTOS : Bruno Col, Coumba Betty Diallo, Ibrahima Diallo, Moussa Kante, Delphine Rouiller. GRAPHIC DESIGN : Sophie Mann www.facebook.com/WorldVisionMauritania Annual Report 2016 MAURITANIA SUMMARY World Vision MAURITANIA 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 World Vision Mauritania in short . .04 A word from the National Director . .05 Strategic Objectives . .06 Education . .08 Health & Nutrition . .12 WASH . .14 Emergencies . .16 Economic Development . .22 Advocacy . .24 Faith and Development . .26 Highlights . .28 Financial Report . .30 Partners . .32 World Vision MAURITANIA 03 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 4 ALGERIA Areas of 14 interventions Programms TIRIS ZEMMOUR WESTERN SAHARA 261 Zouerat Villages 6 Nouadhibou partners PNS ADRAR DAKHLET Atar NOUADHIBOU INCHIRI Akjoujt World Vision Mauritania TAGANT HODH Nouakchott Tidjikdja ECH has a a staff of 139 including CHARGUI ElMira IN SHORT TRARZA 31 women with key positions BRAKNA in almost every department Aleg Ayoun al Atrous Rosso ASSABA Néma Kiffa GORGOL HODH Kaedi EL GHARBI GUDIMAKA Selibaby SENEGAL MALI World Vision MAURITANIA 04 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 A WORD FROM THE NATIONAL DIRECTOR Dear readers, I must hereby pay tribute to the Finally, I can’t forget our projects professional spirit of our program teams that have worked World Vision Mauritania has, by teams that work without respite constantly to raise projects’ my voice, the pleasure to present to mobilize and prepare our local performances to a level that can you its annual report that gives community partners. guarantee a better impact. We an overview on its achievements can’t end without thanking the through the 2016 fiscal year. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Rapport initial du projet Public Disclosure Authorized Amélioration de la Résilience des Communautés et de leur Sécurité Alimentaire face aux effets néfastes du Changement Climatique en Mauritanie Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable ID Projet 200609 Date de démarrage 15/08/2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Date de fin 14/08/2018 Budget total 7 803 605 USD (Fonds pour l’Adaptation) Modalité de mise en œuvre Entité Multilatérale (PAM) Public Disclosure Authorized Septembre 2014 Rapport initial du projet Table des matières Liste des figures ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Liste des tableaux ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Liste des acronymes ................................................................................................................................... 3 Résumé exécutif ........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Historique du projet ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Concept du montage du projet .................................................................................................. -

Mauritania Country Portfolio

Mauritania Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2008. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: IDSEPE manages a portfolio of 16 projects. Total commitment is $1.6 million. Country Program Coordinator: Mr. Sadio Diarra Abdoul Dakel Ly, Project Coordinator BMCI/AFARCO building, 6th floor Tel: +222 44 70 27 27 & +222 22 30 35 04 Country Strategy: The program focuses on working with Avenue Gamal Abder Nassar Email: [email protected] agricultural groups and women’s collectives. P.O Box 1980, Nouakchott, Mauritania Tel: +222 525 29 36 Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Lithi Had El Amme / Iguini El Oula 2014-2017 $94,243 Sector: Agriculture (Vegetables) 3023-MRT Town/City: Wilaya Hodhs -El- Gharbi Summary: The project funds will be used to ensure a reliable water supply to the garden by setting up a borehole extraction system. Funds will allow the Union to expand their cultivation plot to 2 hectares by installing a new irrigation system and building a fence around it to protect it from roaming animals.. Coopérative El Emen Berbâré 2014-2017 $85,527 Sector: Agriculture (Vegetables) 3163-MRT Town/City: Wilaya Hodhs -El- Gharbi Summary: The project funds will be used to install a new irrigation system and fence it to protect it from roaming animals. The Cooperative will set up a borehole extraction system to provide a reliable and constant source of water to the production perimeter. These activities will enable Cooperative members to dramatically increase the volume of vegetables sold and the profit earned by group members. -

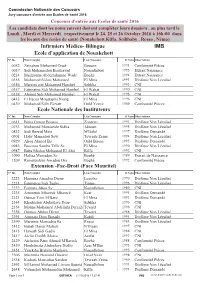

Infirmiers Médico- Bilingue IMB Ecole D'application De Nouakchott Ecole

Commission Nationale des Concours Jury concours d’entrée aux Ecoles de santé 2016 Concours d'entrée aux Ecoles de santé 2016 Les candidats dont les noms suivent doivent compléter leurs dossiers , au plus tard le Lundi , Mardi et Mercredi respectivement le 24, 25 et 26 Octobre 2016 à 16h:00 dans les locaux des écoles de santé (Nouakchott,Kiffa, Seilibaby , Rosso , Néma) Infirmiers Médico- Bilingue IMB Ecole d'application de Nouakchott N° Ins Nom Complet Lieu Naissance D Naiss Observations 0052 Zeinabou Mohamed Cissé Bouanz 1991 Conformité Pièces 0057 Sidi Mohamedou Bouleayad Nouadhibou 1995 Extrait Naissance 0214 Maimouna Abderrahmane Wade Boghé 1994 Extrait Naissance 0355 Mohamed Sidaty Mohamed El Mina 1993 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0356 Mareim sidi Mohamed Hambel Sebkha 1993 CNI 0357 Fatimetou Sidi Mohamed Hambel El Wahat 1990 CNI 0358 Ahmed Sidi Mohamed Hambel El Wahat 1996 CNI 0413 El Hacen Moustapha Niang El Mina 1996 CNI 0439 Mohamed Silly Eleyatt Ould Yengé 1989 Conformité Pièces Ecole Nationale des Instituteurs N° Ins Nom Complet Lieu Naissance D Naiss Observations 0611 Binta Oumar Bousso Zoueratt 1993 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0753 Mohamed Mousseide Sidha Akjoujt 1995 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0832 Sidi Bezeid Mein M'Balal 1997 Diplôme Demandé 0901 Haby Mamadou Sow Tevragh Zeina 1994 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0929 Aliou Ahmed Ba Ould Birom 1995 Diplôme Demandé 0983 Bassirou Samba Tally Sy El Mina 1990 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0987 Baba Medou Mohamed El Abd Kiffa 1992 CNI 1090 Hafssa Mamadou Sy Boghé 1989 Extrait de Naissance 1209 Ramatoulaye Amadou Dia -

Mau136390.Pdf

Article 3: Sont ahrogccs to lites lcs dispositions contraircs, notammcm larrctc N"0750iMII-F IIC/MCI en dale du 06 Mars 200S Iixant les prix de vente maximum des 11) drocarburcs Iiquides. Articlc 4: I.es Sccrctaircx Gcncraux du Ministcrc de ll lydrauliquc. de ITnergie cl des Technologies de I"Information ct de la .Communication. ct du Ministcrc du Commerce ct de lIndustric, ic \\'ali de Nouakchott. lcs Walis des regions. lcs l lakcrns des Moughataas sont charges chacun en ce qui lc conccrnc de lcxccution du present arrete. qui sera public au Journal Olficiel. Arrete 0°1178 du 10 A,riI200SI'i.\anl lc prix de vente Maximum du Ciaillulane, Articlc Premier: PRI X 1)1' VFNTI VRAC-PRIX 1)1 VI Nil: SORTIF-DIPO I a l PRIX IlE vrvrr; VRAC L'lfI -0."\ 'iF PllIX m: nsn ",,'oln \/10\ I'''I \I 15X ')-1 J.75 hi PRIX OF VF\TE • ! IT!'E 10"11811.1 1(,'10' , !'RIX DF n.vrt: /2,51\'(;.\' ! ,I fJ J":GS 2,75 A"GS PRIX I:X CllNDJllli"NI"II'\ I :: :~ j.':; I on I(J.~ I'RIX IX illS /'RIBl'llll" ::I)(J I ! 7(1 ~ jq I'RIX Dr \TN IE NOL!AKCIJllTI 7 1/1/0 :2 JOO I 1()(J 550 'Jln 'AIlIIIIHlI, Articlc 2: PRIX m: VINTF AI 1,1)"'1 All AL X CONSOMMA II I'RS . l.cs prix de vente de vcntes all detail du ga> butane sont lixcs COI1l111C suit: 1044 Journal Otltcicl de la Republiquc Islallliqul'?C Mauntanie 30 Scptcmbre 20GB . -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N

!ho o Õ o !ho !h h !o ! o! o 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 0°0'0" Laayoune / El Aaiun HASSAN I LAAYOUNE !h.!(!o SMARAÕ !(Smara !o ! Cabo Bu Craa Algeria Bojador!( o Western Sahara BIR MOGHREIN 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Ad Dakhla h (!o DAKHLA Tiris Zemmour DAJLA !(! ZOUERAT o o!( FDERIK AIRPORT Zouerate ! Bir Gandus o Nouadhibou NOUADHIBOU (!!o Adrar ! ( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa !h NOUADHIBOU ! Atar (!o ! ATAR Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N AKJOUJT o ! ATLANTIC OCEAN Akjoujt Tagant TIDJIKJA ! o o o Tidjikja TICHITT Nouakchott Nouakchott Hodh Ech Chargui (!o NOUAKCHOTT Nbeika !h.! Trarza ! ! NOUAKCHOTT MOUDJERIA o Moudjeria o !Boutilimit BOUTILIMIT ! Magta` Lahjar o Mal ! TAMCHAKETT Aleg! ! Brakna AIOUN EL ATROUSS !Guerou Bourem PODOR AIRPORTo NEMA Tombouctou! o ABBAYE 'Ayoun el 'Atrous TOMBOUCTOU Kiffa o! (!o o Rosso ! !( !( ! !( o Assaba o KIFFA Nema !( Tekane Bogue Bababe o ! o Goundam! ! Timbedgha Gao Richard-Toll RICHARD TOLL KAEDI o ! Tintane ! DAHARA GOUNDAM !( SAINT LOUIS o!( Lekseiba Hodh El Gharbi TIMBEDRA (!o Mbout o !( Gorgol ! NIAFUNKE o Kaedi ! Kankossa Bassikounou KOROGOUSSOU Saint-Louis o Bou Gadoum !( ! o Guidimaka !( !Hamoud BASSIKOUNOU ! Bousteile! Louga OURO SOGUI AIRPORT o ! DODJI o Maghama Ould !( Kersani ! Yenje ! o 'Adel Bagrou Tanal o !o NIORO DU SAHEL SELIBABY YELIMANE ! NARA Niminiama! o! o ! Nioro 15°0'0"N Nara ! 15°0'0"N Selibabi Diadji ! DOUTENZA LEOPOLD SEDAR SENGHOR INTL Thies Touba Senegal Gouraye! du Sahel Sandigui (! Douentza Burkina (! !( o ! (!o !( Mbake Sandare! -

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

2. Arrêté N°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ Du 24 Août 2006 Fixant Le Nombre De Conseillers Au Niveau De Chaque Commune

2. Arrêté n°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ du 24 août 2006 fixant le nombre de conseillers au niveau de chaque commune Article Premier: Le nombre de conseillers municipaux des deux cent seize (216) Communes de Mauritanie est fixé conformément aux indications du tableau en annexe. Article 2 : Sont abrogées toutes dispositions antérieures contraires, notamment celles relatives à l’arrêté n° 1011 du 06 Septembre 1990 fixant le nombre des conseillers des communes. Article 3 : Les Walis et les Hakems sont chargés, chacun en ce qui le concerne, de l’exécution du présent arrêté qui sera publié au Journal Officiel. Annexe N° dénomination nombre de conseillers H.Chargui 101 Nema 10101 Nema 19 10102 Achemim 15 10103 Jreif 15 10104 Bangou 17 10105 Hassi Atile 17 10106 Oum Avnadech 19 10107 Mabrouk 15 10108 Beribavat 15 10109 Noual 11 10110 Agoueinit 17 102 Amourj 10201 Amourj 17 10202 Adel Bagrou 21 10203 Bougadoum 21 103 Bassiknou 10301 Bassiknou 17 10302 El Megve 17 10303 Fassala - Nere 19 10304 Dhar 17 104 Djigueni 10401 Djiguenni 19 10402 MBROUK 2 17 10403 Feireni 17 10404 Beneamane 15 10405 Aoueinat Zbel 17 10406 Ghlig Ehel Boye 15 Recueil des Textes 2017/DGCT avec l’appui de la Coopération française 81 10407 Ksar El Barka 17 105 Timbedra 10501 Timbedra 19 10502 Twil 19 10503 Koumbi Saleh 17 10504 Bousteila 19 10505 Hassi M'Hadi 19 106 Oualata 10601 Oualata 19 2 H.Gharbi 201 Aioun 20101 Aioun 19 20102 Oum Lahyadh 17 20103 Doueirare 17 20104 Ten Hemad 11 20105 N'saveni 17 20106 Beneamane 15 20107 Egjert 17 202 Tamchekett 20201 Tamchekett 11 20202 Radhi -

Commission Nationale Des Concours Concours D'entrée Aux ENI(S) 2012-2013 Liste Des Admissibles Par Ordre Alphabétique Ecole Annexe

Commission Nationale des Concours Concours d'Entrée aux ENI(s) 2012-2013 Liste des Admissibles par ordre Alphabétique Ecole Annexe Option : Instituteurs Francisants N° Ins Nom Complet Année Naiss Lieu Naiss 0027 Ababacar Abdel Aziz Diop 1984 Sebkha 0005 Abdarrahmane Boubou Niang 1981 Boghe 0142 Abdoul Oumar Ba 1985 Niabina 0063 Abdoulaye Sidi Diop 1986 Teyarett 0060 Aboubacar Moussa Mbaye 1976 Tevragh Zeina 0015 Adam Dioum Diallo 1985 Rosso 0125 adama abdoulaye Sow 1982 Rosso 0025 Adama Cheikhou Traore 1981 Selibaby 0197 Ahmed Abdel kader Ba 1981 Tevragh Zeina 0096 Ahmed Tidjane Yero Sarr 1985 Kiffa 0061 Al Diouma Cheikhna Ndaw 1986 Selibaby 0095 Aly Baila Sall 1984 Nouadhibou 0139 Amadou Ibrahima Sow 1985 Rosso 0159 Amadou Oumar Ba 1984 Sebkha 0045 Aminetou Amadou Dieh 1880 Djeol 0128 Aminetou Mamadou Diallo 1987 Zoueratt 0003 Aminetou Mamadou Seck 1987 Sebkha 0135 Aminetou Med EL Moustapha Limam 1988 Diawnaba 0085 Binta Ghassoum Ba 1987 Bababe 0164 Biry Med Camara 1985 Dafor 0155 Bocar lam Toro Camara 1982 Bababe 0069 Boubacar Billa Yero Sy 1986 Zoueratt 0089 Boudé Gaye Yatera 1981 Boully 0117 Cheikh Oumar Mamadou Anne 1985 Niabina 0175 Cheikh Tidjane Khalidou Ba 1977 Sebkha 0156 Daouda Ousmane Diop 1986 El Mina 0140 Dieynaba Abou Dia 1988 Boghe 0182 Dieynaba Ibrahima Dia 1986 Bababe 0137 Dieynaba Mamadou Ly 1986 Tevragh Zeina 0007 Fatimata Abdoullahi Ba 1985 Bababe 0032 Fatimata Alyou thiam 1987 Nouadhibou 0018 Fatimata Mamadou Sall 1988 Zoueratt 0047 Habsatou Amadou Sy 1985 Aere Mbar 0166 Hacen Ibrahima Lam 1984 Boghe 0078 Hacen Mbaye