The Game Changed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 24, No. 8, Oct, 1979

ON THE INSIDE | If! Iranian woman speaks p. 2 jjj 111 International Marxist-Humanist III Youth Committee p. 7 !j! jjj Editorial: Best UAW contract — for GM p. 5 jjj to WtllKEK^ JftVfcHAL tu»*>"*»*> fl^nu «.»— Worker-author *~th;- f''"^ ^U£**>i* » * + **• **^r- •-lr^ji-K- "\*»«\.#.. naib lies *-f^A„. wws y^.O«"»U tu- »^Si. about book by Charles Denby, Editor Author of Indignant Heart: A Black Worker's Journal The following letter is my response to a slander ous review of my book, Indignant Heart: A Black Work er's Journal, by Manning Marable, an associate pro fessor in the Department of History and Ethnic Studies at the University of San Francisco. Printed in the August 16, 1979 issue of WIN magazine, the review not only has many errors of fact, but is such a serious attack against me that I feel strongly about the need for this immediate reply. * * * 97 Printed in 100 Percent Associate Professor Manning Marable's review of VOL 24—NO. 8 *• ' Union Shop OCTOBER, 1979 my book, Indignant Heart: A Black Worker's Journal, sharply brought to mind what Marx must have meant when he said, "The educators must be educated." Two Worlds For example, Marable knows well that the workers' paper I edit is News & Letters, not News & Notes. This is deliberate falsification. In my book I refer to News & Letters many times. It is not only a workers' news paper, it is the official monthly publication of News and ON THE THRESHOLD OF THE 1980s Letters Committees, the organization of Marxist-Human The following excerpts are taken from the Perspec had been creaking because of its imperialist war in ists in the U.S. -

1999 Newsletter

WAYNE STATE eu er UNJVERSIT)' b r a r y Fall I Winter 1999-2000 Jerome P. Cavanagh Jerome P. Cavanagh was one of the most dynamic and influential mayors in the history of Detroit (1962-1970). Mayor during one of the city's--and America's--most turbulent decades, his career was meteoric, complete with storybook triumphs and great adversi- ties. After winning his first-ever political campaign in 1961 , the 33-year-old mayor soon became a national spokesman for cities, Mayor Jerome P Cavanagh, c. 1966. a shaper of federal urban policies, an advisor to U.S . presidents and one of "urban America's most articulate spokesman." He The Jerome P. Cavanagh also faced what was perhaps Detroit's worst Fellowship for Research in hour when a great civil disorder erupted on city streets in July 1967. Subsequently, until Urban History he left office in 1970, Cavanagh endured great criticism and personal adversity. The Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs The Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection was has established The Jerome P. Cavanagh donated to the Archives of Labor and Urban Fellowship for research in urban history. This award will offer short-term fellowships for Affairs after his death on November 27, research in residence at the Walter P. Reuther It 1979. is a superb resource regarding the Library. history of Detroit during the 1960s. This fellowship will allow researchers to To mark the 20th anniversary of utilize the Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection and Cavanagh's death and the opening of his col- other related collections held by the Reuther lection for research, the Walter P. -

Research Paper

Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Research Paper Detroit: What Lessons for Victoria from a ‘Post-Industrial’ City? No. 2, December 2015 Tom Barnes Research Fellow, Parliamentary Library & Information Service Institute for Religion, Politics and Society Australian Catholic University Level 6, 215 Spring St, Melbourne VIC 3000 [email protected] ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) © 2015 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria. All other material produced by the Parliament -

Five Kingdoms

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Five Kingdoms Kelle Groom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Groom, Kelle, "Five Kingdoms" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3519 FIVE KINGDOMS by KELLE GROOM M.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 B.A. University of Central Florida, 1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing/Poetry in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 Major Professor: Don Stap © 2008 Kelle Groom ii ABSTRACT GROOM, KELLE . Five Kingdoms. (Under the direction of Don Stap.) Five Kingdoms is a collection of 55 poems in three sections. The title refers to the five kingdoms of life, encompassing every living thing. Section I explores political themes and addresses subjects that reach across a broad expanse of time—from the oldest bones of a child and the oldest map of the world to the bombing of Fallujah in the current Iraq war. Connections between physical and metaphysical worlds are examined. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Where in the World? Introduction to Selections and Research Focus .................. 1 The Art of Translation by Khaled Mattawa ................................ 2 UNIT ONE The Americas The Literature of the Americas by Kimberly Koza Harris ..................... 4 Literary Map of the Americas ...................................... 6 An American Classic: Aztec Creation Story ..................... 8 Oral Traditions Aztec Creation Story traditional story ................... 9 Literary Lens: Juxtaposition Focus on Research: Summarize Findings ................... 14 The Literature of Canada ...................................... 15 N Saul Bellow Herzog novel .................................... 16 Literary Lens: Interior Monologue Focus on Research: Quote Sources ...................... 19 Margaret Atwood At the Tourist Centre in Boston short story ............. 20 Literary Lens: Tone Focus on Research: Conduct a Survey .................... 23 N Alice Munro Day of the Butterfly short story ....................... 24 Literary Lens: Theme Focus on Research: Use a Variety of Sources ................ 35 The Literature of Mexico ...................................... 36 Juan Rulfo You Don't Hear Dogs Barking short story ............... 37 Literary Lens: Imagery Focus on Research: Generate Questions ................... 41 N Octavio Paz Two Bodies poem ................................ 42 Literary Lens: Metaphor Focus on Research: Develop a Thesis Statement.............. 44 Carlos Solórzano Crossroads: A Sad Vaudeville drama ................. -

Passenger Car Parts Catalog Information

GENERAL Page INF-2 1964 PASSENGER CAR PARTS CATALOG INFORMATION INDEX TO INFORMATION PAGES PAGE NO. ABBREVIATIONS ............................... INF-19 - ALPHABETICAL INDEX ........................... INF-20 COLOR CODED OR MIXED PART NUMBERS ................. INF-23 COLORED PAGE IDENTIFICATION. ..................... INF-21 ENGINE IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS .................... INF-18 HOW TO LOCATE PARTS. .......................... INF-22 ILLUSTRATIONS ............................... INF-20 INTERFILING REVISION PAGES ....................... LNF - 22 MODEL CODES. ............................... INF- 3 MODEL SPECIFICATIONS ........................... INF- 6 VALIANT PLYMOUTH DART DODGE 880 CHRYSLER IMPERIAL NUMERICAL INDEX ...................... INF-20 ORDERING INFORMATION .......................... INF-23 PAGE NUMBERING. ............................. INF-21 PAINT AND TRIM SPECIFICATIONS. .................... INF- 8 VALIANT PLYMOUTH DART DODGE 880 CHRYSLER IMPERIAL PARTS CATALOG REVISION SERVICE. ................... INF-22 PARTS PACKAGES ............................ INF-21 PART. TYPE CODE SYSTEM ......................... INF-21 BERIAL NUMBERS .............................. INF- 4 SPECIFYING INFORMATION ......................... INF-22 STANDARD PARTS ........................... INF-21 SYMBOLS USED IN THIS CATALOG ..................... INF-18 September 6, 1083. Page INF-a ~bnedhu~~. GENERAL INFORMATION 196-4-P-ASSENGER CAR PARTS CATALOG Page INF-s GENERAL INFORMATION - .. .. This publication contains parts idormation for 1864 Plymouth, Valiant, -

Fight for a Workers' Program to Save Jobs, Homes!

MUNDO OBRERO • La burbuja expansionista de la OTAN 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org OCT. 9, 2008 VOL. 50, NO. 40 50¢ Handout to the rich ignites people’s anger Fight for a workers’ program to save jobs, homes! By Fred Goldstein from below has for the moment overcome are only against government intervention Paulson, Bernanke and company. that might put restraints on the unbridled WHERE’S Sept. 30—The political and financial profit-seeking activity of big business. establishment of U.S. capitalism has been Capitalism’s faithful parties It is hard to tell whether these right- OUR BAILOUT? stunned by the failure of its initial attempt gripped by fear wingers voted “no” out of concerns of to get Congress to pass a $700-billion The growing economic crisis produced ideology or pragmatic protection of their handout to the banks. a political crisis in the two faithful par- seats in the House or both. Whatever their Protests Against a background of bank failures ties of capitalism. On the one hand, the motives, their political rhetoric against across in the U.S. and Europe and appeals from Democratic Party leadership was unable “big government,” which used to be the the White House and the Treasury sec- to force some 40 percent of its members applauded on Wall Street, has suddenly country retary, the House of Representatives on to sign on to this gigantic giveaway to been made obsolete by the present crisis. Sept. 29 defeated the bailout bill, 228 to billionaires this time around, especially The once high-and-mighty tycoons of 205. -

Poetic Commemoration of the Battle in Huleikat Yael Shenker

"The world is filled with remembering and forgetting": Poetic Commemoration of the Battle in Huleikat Yael Shenker and Omri Herzog Abstract The battles fought at Huleikat in the 1948 war tell a tangled and compelling story. Israeli fighters from various brigades fought there in several operations, and the area's conquest in 1948 was strategically significant for Israel. The article focuses on three memories or in fact three strategies of remembering that revolve around the site of these battles: the monument erected at the place, a photograph of Hill 138.5 in Huleikat taken by photographer Drora Dominey that was displayed in an exhibition of Israeli monuments, and a few poems of Yehuda Amichai who fought in that area and lost his close friend Dicky. Emulating terms of analysis proposed by Julia Kristeva this article makes a distinction between semiotic and symbolic memory and argues that Amichai's poetry, like the 138.5 Hill photograph, belongs in a semiotic realm that breaches the limits of consciousness and offers an alternative to national memory. The article further argues that these three memories enable us to trace the painful paths of individual and collective memory as well as the ways in which death mediates among memory, remembering, forgetfulness and obliteration in Israeli culture. The world is filled with remembering and forgetting like sea and dry land. Sometimes memory is the solid ground we stand on, sometimes memory is the sea that covers all things like the Flood. And forgetting is the dry land that saves, like Ararat.1 1 Yehuda Amichai. Patu'ah Sagur Patu'ah (Open Closed Open). -

Utopian Stock: David Constantine Interviewed by Aaron Deveson

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 45.1 March 2019: 3-16 DOI: 10.6240/concentric.lit.201903_45(1).0001 Utopian Stock: David Constantine Interviewed by Aaron Deveson Aaron Deveson Department of English National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan [Editor’s Note] David Constantine, who was born in Salford, Lancashire, in the United Kingdom in 1944, is one of the most consistently brilliant poets and short- story authors writing in English today. In a review of Constantine’s Collected Poems (2004), the critic Stephen (now Stephanie) Burt called him “the most lyrical of good poets” (3), adding that his poetry was “Romantic, in almost all the loaded, unfashionable and daring senses that once-omnipresent word can bear” (3). Constantine’s most recent book of short stories, Tea at the Midland, won the 2013 Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and he has published two novels. He is also one of our most important translators and translation editors. With his wife Helen he edited Modern Poetry in Translation between 2003 and 2012. His translation of Selected Poems by Friedrich Hölderlin was the winner of the European Translation Prize and another of his translations, Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s Lighter than Air, won the Corneliu M. Popescu Prize for European Translation. He has also produced critically lauded translations of Goethe’s Faust, Kleist, Henri Michaux, and Philippe Jaccottet, among others. Before he came to prominence as a writer of poetry and fiction, he was a scholar in European, and especially, German literature. In 1981, Constantine moved from his first academic job at Durham University to the Queen’s College, University of Oxford, where he remains a Supernumerary Fellow, having taught modern languages there until 2000. -

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

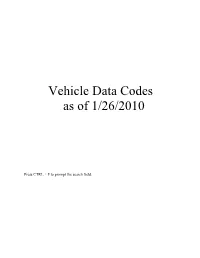

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12 -

Lud Arons 1619 COMMONWEALTH BOSTON,MA 02135 USA

Lud Arons 1619 COMMONWEALTH BOSTON,MA 02135 USA March 9, 1989 Dear Harold Weisberg: I was wondering just when you would recall my interview with you three years ago. My wife thinks that I'm a lousy interviewer and I'm inclined to agree but the program doesn't bore. I think it's lively, candid, disorganized, far-ranging and informative with some interestingly raucous give and take.. If you'd like a copy, I'll whip it into publishable shape from the raw master and dub you a copy @ $12.95 ppd.' If it wasn't for that hack Kopkind and his editor Navasky, we'd probably have never been put into contact again which only goes to prove once again my favorite maxim, "People Do The Right Things For The Wrong Reasons.'" or PI11RTFTWR for short.' I might even include the interview as part or all of an issue of a new audio newsletter you might want to subscribe to & join an elite group of subscribers. I hereby volunteer to go south and spend some time helping you to organize your materials and perhaps even coming up with some gems that can be used to good effect currently instead of having to wait for some improbable scholar from the future Brave One World to find it in an obscure library. Sincerely, 3/9/89 Harolds What do you think about this letter? Do you agree or disagree with it in principle? Februa Dear Journalist: A file accumulated on AIDS related material order has been sent under separate cover to you. -

Guide to the Poetry Center of Chicago Records 1974-2006

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Poetry Center of Chicago Records 1974-2006 © 2009 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Restrictions on Use 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 5 Series I: Administrative 5 Series II: Events and Publications 7 Series III: Audio-Visual 9 Series IV: Broadsides and Posters 9 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.POETRYCENTER Title Poetry Center of Chicago. Records Date 1974-2006 Size 7 linear feet (8 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract The Poetry Center of Chicago was founded in 1973 and is a non-profit arts organization that strives to make poetry accessible to the public through education and events, as well as promote poets' careers. The Poetry Center of Chicago Records contain articles, brochures, posters, correspondence, administrative documents, annual reports, publications, and audio-visual material. Acknowledgments The Poetry Center of Chicago Records were processed and preserved as part of the "Uncovering New Chicago Archives Project," funded with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Information on Use Restrictions on Use Series II, Audio-Visual, does not include access copies for part or all of the material in this series. Researchers will need to consult with staff before requesting material in this series. The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Poetry Center of Chicago. Records, [Box#, Folder#], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Historical Note Though founded in 1973, the groundwork for the Poetry Center of Chicago began in 1968 when Paul Carroll, former editor of Big Table, hosted and organized readings to promote his new Big Table Books series.