Utopian Stock: David Constantine Interviewed by Aaron Deveson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Kingdoms

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Five Kingdoms Kelle Groom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Groom, Kelle, "Five Kingdoms" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3519 FIVE KINGDOMS by KELLE GROOM M.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 B.A. University of Central Florida, 1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing/Poetry in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 Major Professor: Don Stap © 2008 Kelle Groom ii ABSTRACT GROOM, KELLE . Five Kingdoms. (Under the direction of Don Stap.) Five Kingdoms is a collection of 55 poems in three sections. The title refers to the five kingdoms of life, encompassing every living thing. Section I explores political themes and addresses subjects that reach across a broad expanse of time—from the oldest bones of a child and the oldest map of the world to the bombing of Fallujah in the current Iraq war. Connections between physical and metaphysical worlds are examined. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Where in the World? Introduction to Selections and Research Focus .................. 1 The Art of Translation by Khaled Mattawa ................................ 2 UNIT ONE The Americas The Literature of the Americas by Kimberly Koza Harris ..................... 4 Literary Map of the Americas ...................................... 6 An American Classic: Aztec Creation Story ..................... 8 Oral Traditions Aztec Creation Story traditional story ................... 9 Literary Lens: Juxtaposition Focus on Research: Summarize Findings ................... 14 The Literature of Canada ...................................... 15 N Saul Bellow Herzog novel .................................... 16 Literary Lens: Interior Monologue Focus on Research: Quote Sources ...................... 19 Margaret Atwood At the Tourist Centre in Boston short story ............. 20 Literary Lens: Tone Focus on Research: Conduct a Survey .................... 23 N Alice Munro Day of the Butterfly short story ....................... 24 Literary Lens: Theme Focus on Research: Use a Variety of Sources ................ 35 The Literature of Mexico ...................................... 36 Juan Rulfo You Don't Hear Dogs Barking short story ............... 37 Literary Lens: Imagery Focus on Research: Generate Questions ................... 41 N Octavio Paz Two Bodies poem ................................ 42 Literary Lens: Metaphor Focus on Research: Develop a Thesis Statement.............. 44 Carlos Solórzano Crossroads: A Sad Vaudeville drama ................. -

Poetic Commemoration of the Battle in Huleikat Yael Shenker

"The world is filled with remembering and forgetting": Poetic Commemoration of the Battle in Huleikat Yael Shenker and Omri Herzog Abstract The battles fought at Huleikat in the 1948 war tell a tangled and compelling story. Israeli fighters from various brigades fought there in several operations, and the area's conquest in 1948 was strategically significant for Israel. The article focuses on three memories or in fact three strategies of remembering that revolve around the site of these battles: the monument erected at the place, a photograph of Hill 138.5 in Huleikat taken by photographer Drora Dominey that was displayed in an exhibition of Israeli monuments, and a few poems of Yehuda Amichai who fought in that area and lost his close friend Dicky. Emulating terms of analysis proposed by Julia Kristeva this article makes a distinction between semiotic and symbolic memory and argues that Amichai's poetry, like the 138.5 Hill photograph, belongs in a semiotic realm that breaches the limits of consciousness and offers an alternative to national memory. The article further argues that these three memories enable us to trace the painful paths of individual and collective memory as well as the ways in which death mediates among memory, remembering, forgetfulness and obliteration in Israeli culture. The world is filled with remembering and forgetting like sea and dry land. Sometimes memory is the solid ground we stand on, sometimes memory is the sea that covers all things like the Flood. And forgetting is the dry land that saves, like Ararat.1 1 Yehuda Amichai. Patu'ah Sagur Patu'ah (Open Closed Open). -

Lud Arons 1619 COMMONWEALTH BOSTON,MA 02135 USA

Lud Arons 1619 COMMONWEALTH BOSTON,MA 02135 USA March 9, 1989 Dear Harold Weisberg: I was wondering just when you would recall my interview with you three years ago. My wife thinks that I'm a lousy interviewer and I'm inclined to agree but the program doesn't bore. I think it's lively, candid, disorganized, far-ranging and informative with some interestingly raucous give and take.. If you'd like a copy, I'll whip it into publishable shape from the raw master and dub you a copy @ $12.95 ppd.' If it wasn't for that hack Kopkind and his editor Navasky, we'd probably have never been put into contact again which only goes to prove once again my favorite maxim, "People Do The Right Things For The Wrong Reasons.'" or PI11RTFTWR for short.' I might even include the interview as part or all of an issue of a new audio newsletter you might want to subscribe to & join an elite group of subscribers. I hereby volunteer to go south and spend some time helping you to organize your materials and perhaps even coming up with some gems that can be used to good effect currently instead of having to wait for some improbable scholar from the future Brave One World to find it in an obscure library. Sincerely, 3/9/89 Harolds What do you think about this letter? Do you agree or disagree with it in principle? Februa Dear Journalist: A file accumulated on AIDS related material order has been sent under separate cover to you. -

Guide to the Poetry Center of Chicago Records 1974-2006

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Poetry Center of Chicago Records 1974-2006 © 2009 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Restrictions on Use 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 5 Series I: Administrative 5 Series II: Events and Publications 7 Series III: Audio-Visual 9 Series IV: Broadsides and Posters 9 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.POETRYCENTER Title Poetry Center of Chicago. Records Date 1974-2006 Size 7 linear feet (8 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract The Poetry Center of Chicago was founded in 1973 and is a non-profit arts organization that strives to make poetry accessible to the public through education and events, as well as promote poets' careers. The Poetry Center of Chicago Records contain articles, brochures, posters, correspondence, administrative documents, annual reports, publications, and audio-visual material. Acknowledgments The Poetry Center of Chicago Records were processed and preserved as part of the "Uncovering New Chicago Archives Project," funded with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Information on Use Restrictions on Use Series II, Audio-Visual, does not include access copies for part or all of the material in this series. Researchers will need to consult with staff before requesting material in this series. The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Poetry Center of Chicago. Records, [Box#, Folder#], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Historical Note Though founded in 1973, the groundwork for the Poetry Center of Chicago began in 1968 when Paul Carroll, former editor of Big Table, hosted and organized readings to promote his new Big Table Books series. -

Beats and Friends: a Checklist of Audio-Visual Material in the British Library

BEATS AND FRIENDS: A CHECKLIST OF AUDIO-VISUAL MATERIAL IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY Compiled by Steve Cleary CONTENTS Introduction William S. Burroughs Allen Ginsberg Jack Kerouac The East Coast scene John Ashbery Amiri Baraka Ted Berrigan Kenward Elmslie The Fugs John Giorno Ted Joans Robert Kelly Kenneth Koch Tuli Kupferberg Seymour Krim The Living Theatre Gerard Malanga Jonas Mekas Larry Rivers Gilbert Sorrentino The West Coast scene Robin Blaser Richard Brautigan Brother Antoninus Lawrence Ferlinghetti Michael McLure David Meltzer Kenneth Rexroth Gary Snyder Black Mountain Robert Creeley Fielding Dawson Ed Dorn Robert Duncan Larry Eigner Charles Olson John Wieners Jonathan Williams Other Beats Neal Cassady Gregory Corso Brion Gysin Herbert Huncke Jack Micheline Peter Orlovsky Kenneth Patchen Alexander Trocchi Women Carolyn Cassady Diane di Prima Barbara Guest Fran Landesman Denise Levertov Josephine Miles Anne Waldman Influences and connections Paul Bowles Stan Brakhage Lenny Bruce Charles Bukowski Ken Kesey Timothy Leary Norman Mailer Kenneth Patchen Hubert Selby, Jr Alan Watts Wavy Gravy William Carlos Williams Anthologies and Beats in general Giorno Poetry Systems INTRODUCTION A few notes on the criteria underlying this checklist might be helpful. Recordings were selected for inclusion on the basis that they feature Beat (or Beat- connected) writers, performing their own or others' works, in interview, or as the subject of documentary audio or video. Readings - and songs and other tributes to these artists - by artists who would not themselves warrant inclusion have been ignored. Thus Charles Laughton's reading from The Dharma Bums, for example, must be passed over for the purposes of this appendix. BBC Sound Archive material has been included only where also held in the British Library Sound Archive. -

The Game Changed

The Game Changed Lawrence Joseph The Game Changed essays and other prose THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Copyright © 2011 by Lawrence Joseph All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2014 2013 2012 2011 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Joseph, Lawrence, 1948– The game changed : essays and other prose / Lawrence Joseph. p. cm. — (Poets on poetry series) ISBN 978-0-472-07161-6 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472- 05161-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-02774-3 (ebk.) 1. Joseph, Lawrence, 1948– Knowledge—Poetry. 2. Poetry. I. Title. PS3560.O775G36 2011 814'.54—dc22 2011014828 For Laurence Goldstein Acknowledgments “The Poet and the Lawyer: The Example of Wallace Stevens” was presented as a talk at the Eleventh Annual Wallace Stevens Birthday Bash, sponsored by The Hartford Friends of Wallace Stevens, at the Hartford Public Library, on October 7, 2006. “Michael Schmidt’s Lives of the Poets” originally appeared in The Nation, December 13, 1999, under the title “New Poetics (Sans Aristotle).” “A Note on ‘That’s All’” originally appeared, in slightly different form, in Ecstatic Occasions, Expedient Forms, edited by David Lehman (Macmillan, 1987). -

Introduction 23 Yamabe No Akahito 25 William Allingham 25 Yehuda Amichai 26 a R Ammons 26 Anon. 27 Anon. 27 Anon. 28 Anon. 28 An

CONTENTS Introduction 23 Yamabe no Akahito 25 THE MISTS RISE OVER William Allingham 25 WRITING Yehuda Amichai 26 MY FATHER A R Ammons 26 COWARD Anon. 27 'AT SIXTY I, DIONYSIOS' Anon. 27 PRAYER Anon. 28 THE DISTRACTED CENTIPEDE Anon. 28 'QUIETLY SITTING' Anon. 29 ANGELICA THE DOORKEEPER Anon. 29 ICE Guillaume Apollinaire 30 MOUSE W. H. Auden 30 THE AESTHETIC POINT OF VIEW Roy Baume 31 MENU Ambrose Bierce 31 WITH A BOOK Barbara Balch 32 PROBLEM Matsuo Basho 32 THE SUMMER GRASSES HilaireBelloc 33 JULIET E. Clerihew Bentley 33 THE PEOPLE OF SPAIN THINK CERVANTES John Betjeman 34 THE LAST LAUGH Bhartrihari 34 SHE WHO IS ALWAYS IN MY THOUGHTS William Blake ETERNITY 35 Richard Brautigan 35 PLEASE Joseph Brodsky 36 To A FELLOW POET BertoltBrecht 36 SEND ME A LEAF Tom Brown 37 I Do Not Love Thee, Dr Fell Robert Browning 37 RHYME FOR A CHILD John William Burgon 38 PETRA Robert Burns 38 THE BOOK-WORMS Yosa Buson 39 THE WINTER RIVER Mairead Byrne 39 MAHI-MAHI George Gordon, Lord Byron 40 ENDORSEMENT TO THE DEED OF SEPARATION, IN THE APRIL OF 1816 John Cage 40 1 HAVE NOTHING TO SAY' Catullus 41 I LOVE, HATE, HATE LOVE Constantine P Cavafy 41 HE VOWS Ho Chih-Chang 42 WRITTEN ON RETURN HOME Chong Choi 42 SHIJO John Ciardi 43 DAWN OF THE SPACE AGE J. Gordon Coogler 43 A PRETTY GIRL Wendy Cope 44 Two CURES FOR LOVE Cid Corman 44 UNTITLED Stephen Crane 45 TELL ME NOT IN JOYOUS NUMBERS Robert Creeley 45 MORNING Countee Cullen 46 FOR A MOUTHY WOMAN John Cunningham 46 ON ALDERMAN W - Elaine Cusack 47 SHORT THOUGHT Barbara Daniels 47 TROPHY J P Das 48 BEGINNING Charles de lint 48 THE PUPPET Thomas Parke D'Invilliers 49 THEN WEAR THE GOLD HAT John Donne 49 A LAME BEGGAR Carol Ann Duffy 50 MRS DARWIN Richard Eberhart 50 THE ECLIPSE Richard Edwards 51 WHEN I WAS THREE Paul Eluard 51 THE RIVER Marjorie M. -

Yehuda Amichai

Poets, Belief and Calamitous Times . in calamitous times When old certainties lose their outlines, Virtues are negated, and faith fades.1 Gwynith Young Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2006 Department of English University of Melbourne 1 Primo Levi, ‘Huayna Capac’, Collected Poems, (London: Faber & Faber, 1988), 35. ii iii Abstract My research in this thesis covers the religious discourse of six contemporary poets who write belief from a position of calamity. Yehuda Amichai writes from the constant wars fought since the founding of the state of Israel; Anne Sexton from psychiatric illness; Seamus Heaney from the sectarian violence of Ireland; Paul Celan and Nelly Sachs from the twentieth century's greatest calamity, the Holocaust; and Yves Bonnefoy, from the language theories of post-modernism, which are calamitous for a poet. My hypothesis is that under the pressures of calamity, in their resulting fragile subjectivity, poets will write an over-cohesive statement of belief, in which ambiguity and contradiction are suppressed, but that these qualities may be discernable through both traces and gaps in the discourse. In all except one of the poets, I have found this to be the case. Only Nelly Sachs avoids this pattern, and integrates evil and belief. Yehuda Amichai's over-cohesive statement of belief asserts the absence of God and calls God to account. Breaking through this overt discourse however, and dominant by Amichai's final book, is evidence of a nurturing spiritual belief. Anne Sexton repudiates her writing of Christ as Divine mother, companion, liberator and nourisher and reinscribes a patriarchal metanarrative in her 'Rowing' poems. -

HUGHES, TED, 1930-1998. Ted Hughes Papers, 1940-2002

HUGHES, TED, 1930-1998. Ted Hughes papers, 1940-2002 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Hughes, Ted, 1930-1998. Title: Ted Hughes papers, 1940-2002 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 644 Extent: 94.25 linear feet (191 boxes), 13 oversized papers boxes and 5 oversized papers folders (OP), 1 oversized bound volume (OBV), and AV Masters: 1.25 linear feet (2 boxes) Abstract: Papers of British poet laureate Ted Hughes including correspondence, writings by Hughes, materials relating to Sylvia Plath, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, photographs, personal effects and memoriabilia, and audiovisual materials. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply. Letters written by Janos Csokits and Daniel Weissbort are restricted and require the permission of the copyright holder in writing in order to be examined. Letters from Seamus Heaney are closed to researchers for the lifetime of Carol Hughes. Access to selected additional letters are restricted for a period of twenty-five years (2022) or the for the lifetime of Carol Hughes, whichever is greater. See container list for specific restrictions. Special restrictions: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: letters and manuscripts by Ted Hughes and most photographs may not be reproduced without the written permission of Carol Hughes. -

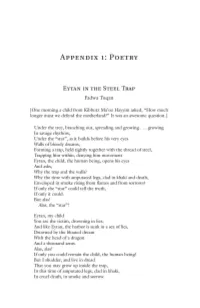

Appendix 1: POETRY

ApPENDIX 1: POETRY EYTAN IN THE STEEL TRAP Fadwa Tuqan [One morning a child from Kibbutz Ma'oz Hayyim asked, "How much longer must we defend the motherland?" It was an awesome question.] Under the tree, branching out, spreading and growing ... growing In savage rhythms, Under the "star", as it builds before his very eyes Walls of bloody dreams, Forming a trap, held tightly together with the thread of steel, Trapping him within, denying him movement Eytan, the child, the human being, opens his eyes And asks, Why the trap and the walls? Why the time with amputated legs, clad in khaki and death, Enveloped in smoke rising from flames and from sorrows? If only the "star" could tell the truth, If only it could. But alas! Alas, the "star"! Eytan, my child You are the victim, drowning in lies, And like Eytan, the harbor is sunk in a sea of lies, Drowned by the bloated dream With the head of a dragon And a thousand arms. Alas, alas! If only you could remain the child, tlle human being! But I shudder, and live in dread That you may grow up inside the trap, In this time of amputated legs, clad in khaki, In cruel death, in smoke and sorrow. 154 ApPENDIX 1 I fear, my child, that the human in you may be smothered, That it may totter and fall- Sinking Sinking Sinking to the bottom of the abyss. (El-Messiri [comp. and trans.] Palestinian Wedding [Washington, DC: Three Continents, 1982]) [ON YOM KIPPUR] Yehuda Amichai On Yom Kippur in 1967, the Year of Forgetting, I put on my dark holiday clothes and walked to the Old City ofJerusalem For a long time I stood in front of an Arab's hole-in-the-wall Shop, not far from the Damascus Gate, a shop with buttons and zippers and spools of thread in every color and snaps and buckles. -

The Concept of the Other in Contemporary Palestinian and Israeli Poetry Masha Itzhaki, Sobhi Boustani

The concept of the Other in Contemporary Palestinian and Israeli Poetry Masha Itzhaki, Sobhi Boustani To cite this version: Masha Itzhaki, Sobhi Boustani. The concept of the Other in Contemporary Palestinian and Israeli Poetry. The Routeledge Handbook of Muslim-Jewish relations, 2016. hal-02197682 HAL Id: hal-02197682 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02197682 Submitted on 30 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 The concept of the Other in Contemporary Palestinian and Israeli Poetry: Nidāʾ Khoury and Mahmoud Darwish, Dalia Rabikovitz and Nathan Zach To be published in: The Routledge Handbook of Muslim-Jewish Relations Cambridge Masha Itzhaki & Sobhi Boustani / INALCO I. The Historic and Linguistic Context It is quite wellknown: Hebrew poetry in Spain constitutes a perfect example of cultural cohabitation between Arabic and Hebrew. It was established in Andalusia at Cordoba in the tenth century under the reign of the Calif ‘Abd al-Rahmân III. It was the product of two extremely powerful cultural sources: classical Arabic poetry on one hand and the language of the Bible on the other. Biblical Hebrew was the primary material used by Jewish poets in Andalusia who search, quite consciously, the linguistic tools for their poems.