It's Not Always Redundant to Assert What Can Be Presupposed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics and Pragmatics Christopher Gauker Semantics deals with the literal meaning of sentences. Pragmatics deals with what speakers mean by their utterances of sentences over and above what those sentences literally mean. However, it is not always clear where to draw the line. Natural languages contain many expressions that may be thought of both as contributing to literal meaning and as devices by which speakers signal what they mean. After characterizing the aims of semantics and pragmatics, this chapter will set out the issues concerning such devices and will propose a way of dividing the labor between semantics and pragmatics. Disagreements about the purview of semantics and pragmatics often concern expressions of which we may say that their interpretation somehow depends on the context in which they are used. Thus: • The interpretation of a sentence containing a demonstrative, as in “This is nice”, depends on a contextually-determined reference of the demonstrative. • The interpretation of a quantified sentence, such as “Everyone is present”, depends on a contextually-determined domain of discourse. • The interpretation of a sentence containing a gradable adjective, as in “Dumbo is small”, depends on a contextually-determined standard (Kennedy 2007). • The interpretation of a sentence containing an incomplete predicate, as in “Tipper is ready”, may depend on a contextually-determined completion. Semantics and Pragmatics 8/4/10 Page 2 • The interpretation of a sentence containing a discourse particle such as “too”, as in “Dennis is having dinner in London tonight too”, may depend on a contextually determined set of background propositions (Gauker 2008a). • The interpretation of a sentence employing metonymy, such as “The ham sandwich wants his check”, depends on a contextually-determined relation of reference-shifting. -

A Cross-Cultural and Pragmatic Study of Felicity Conditions in the Same-Sex Marriage Discourse

Journal of Foreign Languages, Cultures and Civilizations June 2016, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 58-72 ISSN 2333-5882 (Print) 2333-5890 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jflcc.v4n1a7 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jflcc.v4n1a7 A Cross-Cultural and Pragmatic Study of Felicity Conditions in the Same-Sex Marriage Discourse Hashim Aliwy Mohammed Al-Husseini1 & Ghayth K. Shaker Al-Shaibani2 Abstract This paper investigates whether there are Felicity Conditions (FCs) for the same-sex marriage as being a contemporary practice of marriage relations in some countries. As such, the researchers adopt Austin’s (1962) Felicity Conditions (FCs) to examine if conditions of satisfaction are applicable to the same-sex marriage in Christian and Islamic cultures. The researchers focus on analysing and discussing the social, religious, and linguistic conventional procedures of the speech acts of marriage, specifically in the same-sex marriage discourse. We find out that same-sex marriage in Christianity is totally different from the traditional marriage with regard to the social, religious, and linguistic conventions. Consequently, we concluded that same-sex marriage discourse has no FCs in contrast to the traditional marriage in Christianity as well as marriage in Islam which has not changed in form and opposite sex marriage. Keyword: Felicity Conditions; homosexual relations; marriage speech acts; same-sex marriage discourse; conventional procedures 1. Introduction Trosborg (2010, p.3) stated that one can principally affirm that all pragmatic aspects, namely speech act theory and theory of politeness, may be liable to cross-cultural comparisons between two speech communities and/or two cultures. -

Performative Speech Act Verbs in Present Day English

PERFORMATIVE SPEECH ACT VERBS IN PRESENT DAY ENGLISH ELENA LÓPEZ ÁLVAREZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid RESUMEN. En esta contribución se estudian los actos performativos y su influencia en el inglés de hoy en día. A partir de las teorías de J. L. Austin, entre otros autores, se desarrolla un panorama de esta orientación de la filosofía del lenguaje de Austin. PALABRAS CLAVE. Actos performativos, enunciado performativo, inglés. ABSTRACT. This paper focuses on performative speech act verbs in present day English. Reading the theories of J. L. Austin, among others,. With the basis of authors as J. L. Austin, this paper develops a brief landscape about this orientation of Austin’s linguistic philosophy. KEY WORDS. Performative speech act verbs, performative utterance, English. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 1.1. HISTORICAL THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 1.1.1. The beginnings: J.L. Austin The origin of performative speech acts as we know them today dates back to the William James Lectures, the linguistic-philosophical theories devised and delivered by J.L. Austin at Harvard University in 1955, and collected into a series of lectures entitled How to do things with words, posthumously published in 1962. Austin was one of the most influential philosophers of his time. In these lectures, he provided a thorough exploration of performative speech acts, which was an extremely innovative area of study in those days. In the following pages, Austin’s main ideas (together with some comments by other authors) will be presented. 1.1.1.1. Constative – performative distinction In these lectures, Austin begins by making a clear distinction between constative and performative utterances. -

Inquisitive Semantics OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi Inquisitive Semantics OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi OXFORD SURVEYS IN SEMANTICS AND PRAGMATICS general editors: Chris Barker, NewYorkUniversity, and Christopher Kennedy, University of Chicago advisory editors: Kent Bach, San Francisco State University; Jack Hoeksema, University of Groningen;LaurenceR.Horn,Yale University; William Ladusaw, University of California Santa Cruz; Richard Larson, Stony Brook University; Beth Levin, Stanford University;MarkSteedman,University of Edinburgh; Anna Szabolcsi, New York University; Gregory Ward, Northwestern University published Modality Paul Portner Reference Barbara Abbott Intonation and Meaning Daniel Büring Questions Veneeta Dayal Mood Paul Portner Inquisitive Semantics Ivano Ciardelli, Jeroen Groenendijk, and Floris Roelofsen in preparation Aspect Hana Filip Lexical Pragmatics Laurence R. Horn Conversational Implicature Yan Huang OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi Inquisitive Semantics IVANO CIARDELLI, JEROEN GROENENDIJK, AND FLORIS ROELOFSEN 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox dp, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Ivano Ciardelli, Jeroen Groenendijk, and Floris Roelofsen The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms ofa Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives . -

Situation Theory: a Survey

ABSTRACT SITUATION THEORY: A SURVEY Situation semantics was developed as an alternative to possible-worlds semantics. While possible-worlds semantics defines the informational content of sentences in terms of complete descriptions of the way the world is or might be, situation semantics defines the informational content of sentences in terms of partial worlds called situations. Situation theory is a novel informational ontology developed to give situation semantics a rigorous mathematical foundation. In reviewing the literature, we observed that although there are a few texts introducing situation theory in varying levels of detail and systematicity, there has not yet been published, until now, a general survey of the situation-theory literature that might introduce and guide future scholars. We note that a similar, if perhaps less-pressing need exists for a survey of the situation-semantics literature, but regret that we must leave such a survey for others. Jacob Ian Lee December 2011 SITUATION THEORY: A SURVEY by Jacob Ian lee A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science in the College of Science and Mathematics California State University, Fresno December 2011 © 2011 Jacob Ian Lee APPROVED For the Department of Computer Science: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Jacob Ian Lee Thesis Author Todd Wilson (Chair) Computer Science Shigeko Seki Computer Science Shih-Hsi Liu Computer Science For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. -

Exclamatives, Normalcy Conditions and Common Ground

Revue de Sémantique et Pragmatique 40 | 2016 Exclamation et intersubjectivité Exclamatives, Normalcy Conditions and Common Ground Franz d’Avis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rsp/279 DOI: 10.4000/rsp.279 ISSN: 2610-4377 Publisher Presses universitaires d'Orléans Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2017 Number of pages: 17-34 ISSN: 1285-4093 Electronic reference Franz d’Avis, « Exclamatives, Normalcy Conditions and Common Ground », Revue de Sémantique et Pragmatique [Online], 40 | 2016, Online since 01 March 2018, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rsp/279 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rsp.279 Revue de Sémantique et Pragmatique Revue de Sémantique et Pragmatique. 2016. Numéro 40. pp. 17-34. Exclamatives, Normalcy Conditions and Common Ground Franz d’Avis Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz 1. INTRODUCTION The starting point for the search for exclamative sentence types in a lan- guage is often the description of a certain function that utterances of sentences of that type would have. One formulation could be: With the use of an excla- mative sentence, a speaker expresses that the state of affairs described by a proposition given in the sentence is not in accordance with his expectations about the world.1 Exclamative utterances may include an emotional attitude on the part of the speaker, which is often described as surprise in the literature, cf. Altmann (1987, 1993a), Michaelis/Lambrecht (1996), d’Avis (2001), Michaelis (2001), Roguska (2008) and others. Surprise is an attitude that is based on the belief that something unexpected is the case, see from a psychological point of view Reisenzein (2000). -

Felicity Conditions for Counterfactual Conditionals Containing Proper

Counterfactuals in Context: Felicity conditions for counterfactual conditionals containing proper names William Robinson A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Toshiyuki Ogihara Barbara Citko Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Linguistics 2 ©Copyright 2013 William Robinson 3 University of Washington Abstract Counterfactuals in Context: Felicity conditions for counterfactual conditionals containing proper names William Robinson Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Toshiyuki Ogihara PhD Linguistics Linguistics This thesis provides felicity conditions for counterfactual conditionals containing proper names in which essential changes to an individual are counterfactually posited using contrastive focus in either the antecedent or consequent clause. The felicity conditions proposed are an adaptation of Heim’s (1992) CCP Semantics into Kratzer’s (1981) truth conditions for counterfactual conditionals in which the partition function f(w) serves as the local context of evaluation for the antecedent clause, while the set of worlds characterized by the antecedent serves as the local context for the consequent clause. In order for the felicity conditions to generate the right results, it is shown that they must be couched in a rigid designator/essentialist framework inspired by Kripke (1980). This correctly predicts that consequents containing rigid designators are infelicitous when their input context—the set of worlds accessible from the antecedent clause— does not contain a suitable referent. 4 Introduction We use counterfactual conditionals like (1a-b) to make claims about the “ways things could have been,” not about the way things actually are1 (Lewis 1973, p.84). The antecedent clause of a counterfactual conditional posits a change to the actual world from which the consequent clause would/might follow. -

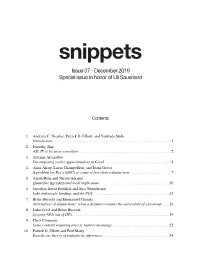

Snippetssnippets

snippetssnippets Issue 37 - December 2019 Special issue in honor of Uli Sauerland Contents 1. Andreea C. Nicolae, Patrick D. Elliott, and Yasutada Sudo Introduction ................................................... ..................1 2. DorothyAhn ASL IX to locus as a modifier ................................................... ..2 3. Artemis Alexiadou Decomposing scalar approximatives in Greek ......................................4 4. Anna Alsop, Lucas Champollion, and Ioana Grosu A problem for Fox’s (2007) account of free choice disjunction ........................7 5. Anton Benz and Nicole Gotzner Quantifier irgendein and local implicature ........................................10 6. Jonathan David Bobaljik and Susi Wurmbrand Fake indexicals, binding, and the PCC ............................................13 7. Brian Buccola and Emmanuel Chemla Alternatives of disjunctions: when a disjunct contains the antecedent of a pronoun ....16 8. LukaCrnicˇ and Brian Buccola Scoping NPIs out of DPs ................................................... .....19 9. Chris Cummins Some contexts requiring precise number meanings .................................22 10. Patrick D. Elliott and Paul Marty Exactly one theory of multiplicity inferences .......................................24 11. Anamaria Fal˘ au¸sand˘ Andreea C. Nicolae Two coordinating particles are better than one: free choice items in Romanian ........27 12. DannyFox Individual concepts and narrow scope illusions ....................................30 13. DannyFox Degree concepts -

Minimal Pronouns1

1 Minimal Pronouns1 Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Bound Variable Pronouns Angelika Kratzer University of Massachusetts at Amherst June 2006 Abstract The paper challenges the widely accepted belief that the relation between a bound variable pronoun and its antecedent is not necessarily submitted to locality constraints. It argues that the locality constraints for bound variable pronouns that are not explicitly marked as such are often hard to detect because of (a) alternative strategies that produce the illusion of true bound variable interpretations and (b) language specific spell-out noise that obscures the presence of agreement chains. To identify and control for those interfering factors, the paper focuses on ‘fake indexicals’, 1st or 2nd person pronouns with bound variable interpretations. Following up on Kratzer (1998), I argue that (non-logophoric) fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features and acquire the remaining features via chains of local agreement relations established in the syntax. If fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features, we need a principled account of what those features are. The paper derives such an account from a semantic theory of pronominal features that is in line with contemporary typological work on possible pronominal paradigms. Keywords: agreement, bound variable pronouns, fake indexicals, meaning of pronominal features, pronominal ambiguity, typologogy of pronouns. 1 . I received much appreciated feedback from audiences in Paris (CSSP, September 2005), at UC Santa Cruz (November 2005), the University of Saarbrücken (workshop on DPs and QPs, December 2005), the University of Tokyo (SALT XIII, March 2006), and the University of Tromsø (workshop on decomposition, May 2006). -

324 10 2 Pragmatics I New Shorter

Speaker’s Meaning, Speech Acts, Topic and Focus, Questions Read: Portner: 24-25,190-198 LING 324 1 Sentence vs. Utterance • Sentence: a unit of language that is syntactically well-formed and can stand alone in discourse as an autonomous linguistic unit, and has a compositionally derived meaning: – A sentence consists of a subject and a predicate: S NP VP. – [[ [NP VP] ]]M,g = 1 iff [[NP]]M,g ∈ [[VP]]M,g • Utterance: The occurrence (use) of a sentence (or possibly smaller constituent that can stand alone) at a given time. • Bill: Sue is coming. Jane: Yes, Sue is coming. – Two utterances of the same sentence. Same meaning. • Bill: “I am tired.” Jane: “ I am tired, too” – Two utterances of the same sentence. Two different meanings. • Semantics studies the meaning of sentences; pragmatics studies the meaning of utterances. LING 324 2 Semantic Meaning vs. Speaker Meaning • A: Most of the people here seem pretty glum. • B: Not everybody. The man drinking champagne is happy. • A: Where? • B: That guy! (pointing) • A: He’s not drinking champagne. He’s drinking sparkling water. The only person drinking champagne is crying on the couch. See? • B: Well, what I meant was that the first guy is happy. [c.f. Donnellan 1966, Kripke 1977] LING 324 3 • The semantic (or expression) meaning of a sentence (or a smaller constituent) is its literal meaning, based on what the words individually mean and the grammar of the language. • The speaker’s meaning of a sentence is what the speaker intends to communicate by uttering it. • These often coincide, but can diverge. -

A Prolegomenon to Situation Semantics

A PROLEGOMENON TO SITUATION SEMANTICS David J. Israel Bolt Beranek and Newman Inc. Cambridge, MA 02238 Situation Semantics (yet?). ABSTRACT So what is there? Besides a few published An attempt is made to prepare Computational papers, each of them containing at least one Linguistics for Situation Semantics. position since abandoned~ there is a book ~ Attitudes literally on the very I INTRODUCTION verge of publication. This contains the philosophlcal/theoretlcal background of the program The editors of the AI Journal recently hit upon - The Big Picture. It also contains a very brief the nice notion of correspondents' columns. The treatment of a very simple fragment of ALIASS. And basic idea was to solicit experts in various what, the reader may well ask is ALIASS? An fields, both within and outside of Artificial Artificial Language for lliustratlng Aspects of Intelligence, to provide "guidance to important, ~Ituation ~emantlcs, that's what. Moreover there interesting current literature" in their fields. is in the works a ceiiaboratlve effort, to be For Philosophy, they made the happy choice of Dan called Situations andS. m This will contain Dennett; for natural language processing, the a "Fragment of Situation Semantics", a treatment of equally happy choice of Barbara Grosz. Each has so an extended fra~ent of ~. Last, for the far contributed one column, and these early moment, but not least, is a second book by Barwise contributions overlap in one, and as it happens, and Perry, ~ ~, which will include only one, particular; to wit: Situation~manties. a treatment of an even more extended fragment of Witness Dennett: English, together with a self-contalned treatment of the technical, mathematical background. -

Constructional Meaning and Compositionality

Constructional Meaning and Compositionality Paul Kay International Computer Science Institute and Department of Linguistics University of California, Berkeley 5 Laura A. Michaelis Department of Linguistics and Institute of Cognitive Science University of Colorado Boulder Contents 10 1. Constructions and compositionality 2. Continuum of idiomaticity 3. Kinds of constructional meanings 4. Model-theoretic and truth-conditional meaning 5. Argument structure 15 6. Metalinguistic constructions 7. Less commonly recognized illocutionary forces 8. Conventional implicature, or pragmatic presupposition 9. Information flow 10. Conclusion 20 11. References Abstract One of the major motivations for constructional approaches to grammar is that a given rule of syntactic formation can sometimes, in fact often, be associated with more than one semantic 25 specification. For example, a pair of expressions like purple plum and alleged thief call on different rules of semantic combination. The first involves something closely related to intersection of sets: a purple plum is a member of the set of purple things and a member of the set of plums. But an alleged thief is not a member of the intersection of the set of thieves and the set of alleged things. Indeed, that intersection is empty, since only a proposition 30 can be alleged and a thief, whether by deed or attribution, is never a proposition. This chapter describes the various ways meanings may be assembled in a construction-based grammar. 1. Constructions and compositionality 35 It is sometimes supposed that constructional approaches are opposed to compositional semantics. This happens to be an incorrect supposition, but it is instructive to consider why it exists.