Konturen V (2014) 3 Obrist / Worringer / Marc Abstraction and Empathy On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Final Report Provenance Research

Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation Final Report Project management Dr. Thorsten Sadowsky, Director Annick Haldemann, Registrar [email protected] Project handling and report Julia Sophie Syperreck MA, Research Assistant [email protected] 31 August 2018 Kirchner Museum Davos Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 2 Contents 3 I. Work report 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project 5 b. Work performed by the project staff and project schedule 6 c. Methodical approach and manner of publication of the findings 7 d. Object statistics 9 e. List of the historical agents (individuals and institutions) relevant to the project 10 f. Documentation of the findings for third parties 11 II. Summary 12 a. Evaluation of the findings 12 b. Unresolved issues and need for further research 13 III. Appendix: List of works Kirchner Museum Davos I. Work report Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project At the beginning of the project an assessment was made which groups of works within the collection are more likely to be linked to the “liquidation” of private and public collections during the Nazi dictatorship in Germany in the years from 1933 to 1945. It was found that there is only very patchy provenance information for the forty-two artworks donated in 2000 to the Kirchner Museum Davos by “Rosemarie and Konrad Baumgart-Möller in memory of Ferdinand Möller, Berlin.” Since “Möller” is one of the red-flag names in provenance research, the investigation of this part of the collection was given priority. -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

Franz Marc Animals Fine Art Pages

Playing Weasels Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1909 Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Franz Marc was a German painter and printmaker that lived from 1880 to 1916. He studied in Munich and in France. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Siberian Sheepdogs Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1910 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Post-Impressionism Interesting Fact: While serving in the German military in World War I, Marc painted tarp covers in various artistic styles, ranging “from Manet to Kandinsky” in hopes of hiding artillery. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Blue Horse I Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Deer in the Snow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Donkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Most of Marc’s work portrays animals in a very stark way, using bold colors. His style caught the attention of the art world. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Monkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Interesting Fact: A “frieze” is a wide horizontal painting or other decoration, often displayed on a wall near the ceiling. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Resting Cows Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com The Yellow Cow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: The style of Expressionism was a modern form of art that began in the early 1900s. -

Der Kunsthistoriker Wilhelm Worringer Und Seine Frau Die Malerin Marta

Gefördert durch die www.digiporta.net Der Kunsthistoriker Wilhelm Worringer und seine Frau die Malerin Marta Porträtierte Person: Worringer, Wilhelm Verweisung: Worringer, Wilhelm R. Voringer, Vilchem Worringer, Wilhelm Robert 沃林格 Kurzbiografie: Wilhelm Worringer wurde 1881 in Aachen geboren. Er war verheiratet mit der Künstlerin Marta Worringer (1881-1965). Zunächst Literaturwissenschaftler, wechselte Worringer bald zur DKA_NLNauhausWilhelm_IIIA1-0002 Kunstgeschichte und studierte bei Heinrich Rückert, Georg Simmel und Heinrich Wölfflin. Seine methodische Herangehensweise präsentierte sich vor allem in seiner Dissertation Abstraktion und Einfühlung bei Artur Weese in Bern im Jahre 1907. Nach seiner Habilitation (ebenso in Bern 1909) unter dem Titel Formprobleme der Gotik lehrte Worringer ab 1915 als Privatdozent und ab 1925 für drei Jahre als außerordentlicher Professor am Kunsthistorischen Institut der Universität Bonn. 1928 wurde er Professor an der Universität Königsberg. Hier blieb er von 1933 bis 1945 als einziger deutscher Kunsthistoriker in innerer Emigration, indem er seine Publikationen einstellte. Nach dem Krieg im Jahre 1945 trat er eine Professur an der Universität Halle an, verließ jedoch die DDR 1950 aus politischen Gründen. Im Jahr 1965 verstarb er in München. Lebensdaten: 1881 - 1965 Geburtsort: Aachen Sterbeort: München Land: Deutschland Berufsindex: Kunsthistoriker, Kunsttheoretiker Normdaten: DNB: 118807900 DBpedia: Wilhelm_Worringer VIAF: 27143983 Quellen: Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Wikipedia Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek Deutsche Biographie, NDB/ADB www.digiporta.net Seite 1 von 3 Literatur: Bibliotheksverbund Bayern, B3Kat (110 Einträge) Bibliotheken der Universität Heidelberg (35 Einträge) Weitere Porträts: DIGIPORTA (9 Einträge) Nachlass-Nachweis: KALLIOPE Worringer, Marta Verweisung: Worringer, Marta Maria Emilie Schmitz, Marta Schmitz, Marta Maria Emilie Kurzbiografie: Die 1881 in Köln geborene Marta Schmitz besuchte in Düsseldorf und München Kunstschulen und war in Bern Schülerin von Cuno Amiet. -

375-402 Levy:145-000 Paviot 25.04.11 11:32 Seite 375

375-402 Levy:145-000 Paviot 25.04.11 11:32 Seite 375 Evonne Levy The German Art Historians of World War I: Grautoff, Wichert, Weisbach and Brinckmann and the activities of the Zentralstelle für Auslandsdienst »Diese Tätigkeit, die mich über mein Fach hinaus experience of war shaped the discipline and its zu einem Umblick auf weitere Gebiete nötigte – protagonists will be difficult to reconstruct to the und zu einer Zeit, die einen an äussere Ereignisse extent that it is a personal story.2 fesselte und wissenschaftlicher Konzentration Yet the Great War also saw the participation of nicht günstig war –, habe ich niemals bereut.« art historians in a variety of official capacities whose impact was of a more public and measur - – Werner Weisbach about his work for the able nature. Patriotic German museum directors Zentralstelle für Auslandsdienst during World War I1 and curators, university faculty and the legions of newly minted Ph.D.s headed for work in publishing or journalism applied scholarly skills Introduction and tools in the first total war effort to the pro- World War I was the first international conflict tection of art (Kunstschutz) or in the new propa- that took place after the consolidation of art his - ganda offices that sprang up in neutral and oc - tory as a discipline in Germany. It saw countless cupied territories. Even reluctant pacifists like students and young faculty endure battle and lose Heinrich Wölfflin participated by giving lectures their lives. While in the battlefield some soldiers in war zones3 and providing much succour to read the specialized publications on art written students in the field by corresponding devotedly for them, or carried in their pockets the guides to with them. -

Dissident Artists' Associations of Germany 1892-1912

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1984 Dissident Artists' Associations of Germany 1892-1912 Mary Jo Eberspacher Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Eberspacher, Mary Jo, "Dissident Artists' Associations of Germany 1892-1912" (1984). Masters Theses. 2826. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2826 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced -

Stellvertretung As Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Samuel Paul Randall St. Edmund’s College December 2018 Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Abstract Stellvertretung represents a consistent and central hermeneutic for Bonhoeffer. This thesis demonstrates that, in contrast to other translations, a more precise interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s use of Stellvertretung would be ‘vicarious suffering’. For Bonhoeffer Stellvertretung as ‘vicarious suffering’ illuminates not only the action of God in Christ for the sins of the world, but also Christian discipleship as participation in Christ’s suffering for others; to be as Christ: Schuldübernahme. In this understanding of Stellvertretung as vicarious suffering Bonhoeffer demonstrates independence from his Protestant (Lutheran) heritage and reflects an interpretation that bears comparison with broader ecumenical understanding. This study of Bonhoeffer’s writings draws attention to Bonhoeffer’s critical affection towards Catholicism and highlights the theological importance of vicarious suffering during a period of renewal in Catholic theology, popular piety and fictional literature. Although Bonhoeffer references fictional literature in his writings, and indicates its importance in ethical and theological discussion, there has been little attempt to analyse or consider its contribution to Bonhoeffer’s theology. This thesis fills this lacuna in its consideration of the reception by Bonhoeffer of the writings of Georges Bernanos, Reinhold Schneider and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Each of these writers features vicarious suffering, or its conceptual equivalent, as an important motif. According to Bonhoeffer Christian discipleship is the action of vicarious suffering (Stellvertretung) and of Verantwortung (responsibility) in love for others and of taking upon oneself the Schuld that burdens the world. -

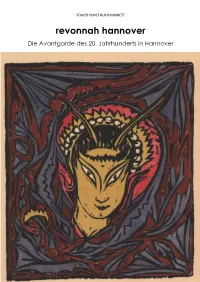

Revonnah Hannover Die Avantgarde Des 20

STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT revonnah hannover Die Avantgarde des 20. Jahrhunderts in Hannover 1 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT Katalog 3 Herbst 2018 Stader Kunst-Buch-Kabinett Antiquariat Michael Schleicher Schützenstrasse 12 21682 Hansestadt STADE Tel +49 (0) 4141 777 257 Email [email protected] Abbildungen Umschlag: Katalog-Nummern 67 und 68; Katalog-Nummer 32. Preise in EURO (€) Please do not hesitate to contact me: english descriptions available upon request. 2 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT 1 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Vorwort). I. Sonderausstellung Max Liebermann Gemälde Handzeichnungen. 1. Oktober - 5. November [1916]. Hannover, Königstr. 8. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1916, ca. 19,8 x 14,5 cm, (16) Seiten, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original-Klammerheftung. Umschlag etwas fleckig, Rückendeckel mit handschriftlichen Zahlenreihen, sonst ein gutes Exemplar. 280,-- Kestnerchronik 1, 29. - Schmied 1 (Abbildung des Umschlages Seite 238). - Literatur: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Hannover, Kunstverein, 1962. - Schmied, Wieland, Wegbereiter zur modernen Kunst, 50 Jahre Kestner Gesellschaft, 1966. - Kestnerchronik, Kestnergesellschaft, Buch 1, 2006. - REVONNAH, Kunst der Avantgarde in Hannover 1912-1933, Sprengel Museum, 2017. 2 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Text). III. Sonderausstellung Willy Jaeckel Gemälde u. Graphik. 17. Dezember 1916 - 17. Januar 1917. Hannover, Königstrasse 8. Zeitgleich mit Walter Alfred Rosam und Ludwig Vierthaler (Verzeichnis auf lose einliegendem Doppelblatt). Verkäufliche Arbeiten mit den gedruckten Preisangaben. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1917, ca. 19,7 x 14,4 cm, (16) Seiten, (4) Seiten Einlagefaltblatt als Ergänzung zum Katalog, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original- Klammerheftung (Klammern oxidiert). Im oberen Bereich alter Feuchtigkeitsschaden; die Seiten sind nicht verklebt. -

The Blue Rider

THE BLUE RIDER 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 1 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 2 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 2 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 HELMUT FRIEDEL ANNEGRET HOBERG THE BLUE RIDER IN THE LENBACHHAUS, MUNICH PRESTEL Munich London New York 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 3 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 4 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 CONTENTS Preface 7 Helmut Friedel 10 How the Blue Rider Came to the Lenbachhaus Annegret Hoberg 21 The Blue Rider – History and Ideas Plates 75 with commentaries by Annegret Hoberg WASSILY KANDINSKY (1–39) 76 FRANZ MARC (40 – 58) 156 GABRIELE MÜNTER (59–74) 196 AUGUST MACKE (75 – 88) 230 ROBERT DELAUNAY (89 – 90) 260 HEINRICH CAMPENDONK (91–92) 266 ALEXEI JAWLENSKY (93 –106) 272 MARIANNE VON WEREFKIN (107–109) 302 ALBERT BLOCH (110) 310 VLADIMIR BURLIUK (111) 314 ADRIAAN KORTEWEG (112 –113) 318 ALFRED KUBIN (114 –118) 324 PAUL KLEE (119 –132) 336 Bibliography 368 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 5 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 6 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 PREFACE 7 The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), the artists’ group formed by such important fi gures as Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, Alexei Jawlensky, and Paul Klee, had a momentous and far-reaching impact on the art of the twentieth century not only in the art city Munich, but internationally as well. Their very particular kind of intensely colorful, expressive paint- ing, using a dense formal idiom that was moving toward abstraction, was based on a unique spiritual approach that opened up completely new possibilities for expression, ranging in style from a height- ened realism to abstraction. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I am using the terms ‘space’ and ‘place’ in Michel de Certeau’s sense, in that ‘space is a practiced place’ (Certeau 1988: 117), and where, as Lefebvre puts it, ‘(Social) space is a (social) product’ (Lefebvre 1991: 26). Evelyn O’Malley has drawn my attention to the anthropocentric dangers of this theorisation, a problematic that I have not been able to deal with fully in this volume, although in Chapters 4 and 6 I begin to suggest a collaboration between human and non- human in the making of space. 2. I am extending the use of the term ‘ extra- daily’, which is more commonly associated with its use by theatre director Eugenio Barba to describe the per- former’s bodily behaviours, which are moved ‘away from daily techniques, creating a tension, a difference in potential, through which energy passes’ and ‘which appear to be based on the reality with which everyone is familiar, but which follow a logic which is not immediately recognisable’ (Barba and Savarese 1991: 18). 3. Architectural theorist Kenneth Frampton distinguishes between the ‘sceno- graphic’, which he considers ‘essentially representational’, and the ‘architec- tonic’ as the interpretation of the constructed form, in its relationship to place, referring ‘not only to the technical means of supporting the building, but also to the mythic reality of this structural achievement’ (Frampton 2007 [1987]: 375). He argues that postmodern architecture emphasises the scenographic over the architectonic and calls for new attention to the latter. However, in contemporary theatre production, this distinction does not always reflect the work of scenographers, so might prove reductive in this context. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215/842-6353 CONTACT: Katie Ziglar Deb Spears (202) 842-6353 ** Press preview: Wednesday, November 15, 1989 EXPRESSIONIST AND OTHER MODERN GERMAN PAINTINGS AT NATIONAL GAT.T.KRY Washington, D.C., September 18, 1989 Thirty-four outstanding German paintings from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection begin an American tour at the National Gallery of Art, November 19, 1989 through January 14, 1990. Expressionism and Modern German Painting from the Thyssen- Bornemisza Collection contains important examples by artists whose major paintings are extremely rare in this country. The nineteen artists represented in the show include Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Otto Dix, Johannes Itten, Franz Marc, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The intense and colorful works in this exhibition are among the modern paintings Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza has added, along with old master paintings, to the collection he inherited from his father> Baron Heinrich (1875-1947). Expressionism and Modern German Painting, to be seen at three American museums, is selected from the large collection on view at the Baron's home, Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland, through October 29, 1989. It is the first exhibition devoted entirely to the modern German paintings in the collection. -more- expressionism and modern german painting . page two "Comprehensive groupings of expressionism and modern German paintings are extremely rare in American museums and we are pleased to offer a show of this extraordinary caliber here this fall," said J. Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery. The American show has been selected by Andrew Robison, senior curator at the National Gallery.