Literacy Revolution: How the New Tools of Communication Change the Stories We Tell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

Evolution of the Infographic

EVOLUTION OF THE INFOGRAPHIC: Then, now, and future-now. EVOLUTION People have been using images and data to tell stories for ages—long before the days of the Internet, smartphones, and Excel. In fact, the history of infographics pre-dates the web by more than 30,000 years with the earliest forms of these visuals being cave paintings that helped early humans find food, resources, and shelter. But as technology has advanced, so has our ability to tell meaningful stories. Here’s a look into the evolution of modern infographics—where they’ve been, how they’ve evolved, and where they’re headed. Then: Printed, static infographics The 20th Century introduced the infographic—a staple for how we communicate, visualize, and share information today. Early on, these print graphics married illustration and data to communicate information in a revolutionary way. ADVANTAGE Design elements enable people to quickly absorb information previously confined to long paragraphs of text. LIMITATION Static infographics didn’t allow for deeper dives into the data to explore granularities. Hoping to drill down for more detail or context? Tough luck—what you see is what you get. Source: http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-01/16/painting- by-numbers-at-london-transport-museum INFOGRAPHICS THROUGH THE AGES DOMO 03 Now: Web-based, interactive infographics While the first wave of modern infographics made complex data more consumable, web-based, interactive infographics made data more explorable. These are everywhere today. ADVANTAGE Everyone looking to make data an asset, from executives to graphic designers, are now building interactive data stories that deliver additional context and value. -

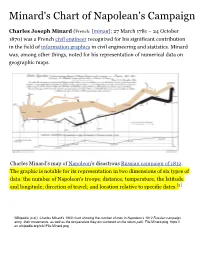

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE:Vietnam Veterans Memorial LOCATION: Washington, D.C., U.S. DATE: . 1982 C.E. ARTIST: Maya Lin PERIOD/STYLE: Minimalism PATRON: The Commision of Fine Arts MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: Granite FORM: Highly reflective black granite with incised names of 58,000 names ofVietnam Veterans who sacrificed their lives during the conflict. The name is an abstraction that means more to the family and friends than a pictorial representation. The two walls start very short and get progressively taller until they meet at an oblique angle at the monument’s center. One wall points towards the Washington Monument; the other points to the Lincoln Memorial. FUNCTION: It functions as a memorial to the soldiers that died during the Vietnam War. It is an ideal place for people to come and spend quiet time reflecting on the names and perhaps leaving mementos to the deceased. CONTENT: The walls are made of a dark igneous rock called gabbro, a type of granite, which is highly reflective when polished.The surface of the monument is etched with the 58,195 names of the Americans who died or remained missing in action in the Vietnam War. The names are listed in the order in which they were reported killed or missing in action. This makes the names harder to find, and re- quires a listing and numeric system of organization for visitors. CONTEXT: There were 1400 anonymous entries for this commission. There was a real backlash once her identity was known because of latent racism in the post Vietnam era. She defended her design in front of the United States Congress, who eventually reached a compro- mise: A group of more “traditional” sculptures, called “The Three Soldiers,” was erected near the monument. -

Time and Animation

TIME AND ANIMATION Petra Isenberg (&Pierre Dragicevic) TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION 2 TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION Time 3 VISUALIZATION OF TIME 4 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? 5 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? What data type is it? • Nominal? • Ordinal? • Quantitative? 6 TIME Ordinal Quantitative • Discrete • Continuous Aigner et al, 2011 7 TIME Joe Parry, 2007. Adapted from Mackinlay, 1986 8 TIME Periodicity • Natural: days, seasons • Social: working hours, holidays • Biological: circadian, etc. Has many subdivisions (units) • Years, months, days, weeks, H, M, S Has a specific meaning • Not captured by data type • Associations, conventions • Pervasive in the real-world • Time visualizations often considered as a separate type 9 TIME Shneiderman: • 1-dimensional data • 2-dimensional data • 3-dimensional data • temporal data • multi-dimensional data • tree data • network data 10 VISUALIZING TIME as a time point 11 VISUALIZING TIME as a time period 12 VISUALIZING TIME as a duration 13 VISUALIZING TIME PLUS DATA 14 MAPPING TIME TO SPACE 15 MAPPING TIME TO AN AXIS Time Data 16 TIME-SERIES DATA From a Statistics Book: • A set of observations xt, each one being recorded at a specific time t From Wikipedia: • A sequence of data points, measured typically at successive time instants spaced at uniform time intervals 17 LINE CHARTS Aigner et al, 2011 18 LINE CHARTS Marey’s Physiological Recordings Plethysmograph Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) Pneumogram Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) 19 LINE CHARTS Pendulum Seismometer (image source) Andrea Bina, 1751 Possibly also 17th century (source) 20 LINE CHARTS Inclinations of planetary orbits Macrobius, 10th or 11th century cited in Kendall, 1990 21 Marey’s Train Schedule LINE CHARTS 6 PARIS LYON 7 22 Étienne-Jules Marey, 1885, cited in Tufte, 1983 OTHER CHARTS Line Plots Point Plots Silhouette Graphs Bar Charts Aigner et al, 2011 23 OTHER CHARTS Combination - New York Times Weather Chart New York Times, 1980. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Impeded Language in EE Cummings' Poetry and Xu

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1995 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky Anna Neher Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Neher, Anna, "Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky" (1995). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 262. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/262 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY An equal opportunity university Honors■ Program HONORS THESIS In presenting this Honors paper in partial requirements for a bachelor ’s degree at Western Washington University, 1 agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial purposes or for financial 2 ain shall not be allowed without mv written permission. Signature Date G- Anna Neher 1 Anna Neher Dr. Melissa Walt Honors Senior Project June 10, 2005 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky ”In the twentieth century as never before, form calls attention to itself.. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

Capítulo 1 Análise De Sentimentos Utilizando Técnicas De Classificação Multiclasse

XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação De 17 a 20 de maio de 2016 Florianópolis – SC Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação: Minicursos SBSI 2016 Sociedade Brasileira de Computação – SBC Organizadores Clodis Boscarioli Ronaldo dos Santos Mello Frank Augusto Siqueira Patrícia Vilain Realização INE/UFSC – Departamento de Informática e Estatística/ Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Promoção Sociedade Brasileira de Computação – SBC Patrocínio Institucional CAPES – Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior CNPq - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico FAPESC - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina Catalogação na fonte pela Biblioteca Universitária da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina S612a Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação (12. : 2016 : Florianópolis, SC) Anais [do] XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação [recurso eletrônico] / Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação: Minicursos SBSI 2016 ; organizadores Clodis Boscarioli ; realização Departamento de Informática e Estatística/ Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ; promoção Sociedade Brasileira de Computação (SBC). Florianópolis : UFSC/Departamento de Informática e Estatística, 2016. 1 e-book Minicursos SBSI 2016: Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação Disponível em: http://sbsi2016.ufsc.br/anais/ Evento realizado em Florianópolis de 17 a 20 de maio de 2016. ISBN 978-85-7669-317-8 1. Sistemas de recuperação da informação Congressos. 2. Tecnologia Serviços de informação Congressos. 3. Internet na administração pública Congressos. I. Boscarioli, Clodis. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Departamento de Informática e Estatística. III. Sociedade Brasileira de Computação. IV. Título. CDU: 004.65 Prefácio Dentre as atividades de Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação (SBSI) a discussão de temas atuais sobre pesquisa e ensino, e também sua relação com a indústria, é sempre oportunizada. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

The Forgotten Discovery of Gravity Models and the Inefficiency of Early

The forgotten discovery of gravity models and the inefficiency of early railway networks Andrew Odlyzko School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA [email protected] http://www.dtc.umn.edu/∼odlyzko Revised version, April 19, 2015 Abstract. The routes of early railways around the world were generally inef- ficient because of the incorrect assumption that long distance travel between major cities would dominate. Modern planners rely on methods such as the “gravity models of spatial interaction,” which show quantitatively the impor- tance of accommodating travel demands between smaller cities. Such models were not used in the 19th century. This paper shows that gravity models were discovered in 1846, a dozen years earlier than had been known previously. That discovery was published during the great Railway Mania in Britain. Had the validity and value of gravity models been recognized properly, the investment losses of that gigantic bubble could have been lessened, and more efficient rail systems in Britain and many other countries would have been built. This incident shows society’s early encounter with the “Big Data” of the day and the slow diffusion of economically significant information. The results of this study suggest that it will be increasingly feasible to use modern network science to analyze information dissemination in the 19th century. That might assist in understanding the diffusion of technologies and the origins of bubbles. Keywords: gravity models, railway planning, diffusion of information JEL classification codes: D8, L9, N7 1 Introduction Dramatic innovations in transportation or communication frequently produce predictions that distance is becoming irrelevant. In recent decades, two popular books in this genre introduced the concepts of “death of distance” [7] and “the Earth is flat” [25].