Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

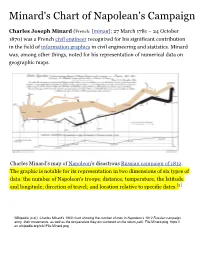

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

Time and Animation

TIME AND ANIMATION Petra Isenberg (&Pierre Dragicevic) TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION 2 TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION Time 3 VISUALIZATION OF TIME 4 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? 5 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? What data type is it? • Nominal? • Ordinal? • Quantitative? 6 TIME Ordinal Quantitative • Discrete • Continuous Aigner et al, 2011 7 TIME Joe Parry, 2007. Adapted from Mackinlay, 1986 8 TIME Periodicity • Natural: days, seasons • Social: working hours, holidays • Biological: circadian, etc. Has many subdivisions (units) • Years, months, days, weeks, H, M, S Has a specific meaning • Not captured by data type • Associations, conventions • Pervasive in the real-world • Time visualizations often considered as a separate type 9 TIME Shneiderman: • 1-dimensional data • 2-dimensional data • 3-dimensional data • temporal data • multi-dimensional data • tree data • network data 10 VISUALIZING TIME as a time point 11 VISUALIZING TIME as a time period 12 VISUALIZING TIME as a duration 13 VISUALIZING TIME PLUS DATA 14 MAPPING TIME TO SPACE 15 MAPPING TIME TO AN AXIS Time Data 16 TIME-SERIES DATA From a Statistics Book: • A set of observations xt, each one being recorded at a specific time t From Wikipedia: • A sequence of data points, measured typically at successive time instants spaced at uniform time intervals 17 LINE CHARTS Aigner et al, 2011 18 LINE CHARTS Marey’s Physiological Recordings Plethysmograph Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) Pneumogram Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) 19 LINE CHARTS Pendulum Seismometer (image source) Andrea Bina, 1751 Possibly also 17th century (source) 20 LINE CHARTS Inclinations of planetary orbits Macrobius, 10th or 11th century cited in Kendall, 1990 21 Marey’s Train Schedule LINE CHARTS 6 PARIS LYON 7 22 Étienne-Jules Marey, 1885, cited in Tufte, 1983 OTHER CHARTS Line Plots Point Plots Silhouette Graphs Bar Charts Aigner et al, 2011 23 OTHER CHARTS Combination - New York Times Weather Chart New York Times, 1980. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

The Forgotten Discovery of Gravity Models and the Inefficiency of Early

The forgotten discovery of gravity models and the inefficiency of early railway networks Andrew Odlyzko School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA [email protected] http://www.dtc.umn.edu/∼odlyzko Revised version, April 19, 2015 Abstract. The routes of early railways around the world were generally inef- ficient because of the incorrect assumption that long distance travel between major cities would dominate. Modern planners rely on methods such as the “gravity models of spatial interaction,” which show quantitatively the impor- tance of accommodating travel demands between smaller cities. Such models were not used in the 19th century. This paper shows that gravity models were discovered in 1846, a dozen years earlier than had been known previously. That discovery was published during the great Railway Mania in Britain. Had the validity and value of gravity models been recognized properly, the investment losses of that gigantic bubble could have been lessened, and more efficient rail systems in Britain and many other countries would have been built. This incident shows society’s early encounter with the “Big Data” of the day and the slow diffusion of economically significant information. The results of this study suggest that it will be increasingly feasible to use modern network science to analyze information dissemination in the 19th century. That might assist in understanding the diffusion of technologies and the origins of bubbles. Keywords: gravity models, railway planning, diffusion of information JEL classification codes: D8, L9, N7 1 Introduction Dramatic innovations in transportation or communication frequently produce predictions that distance is becoming irrelevant. In recent decades, two popular books in this genre introduced the concepts of “death of distance” [7] and “the Earth is flat” [25]. -

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods Spring Semester 2009 Project One Jessica Anderson Utah State University Department of Mathematics and Statistics 3900 Old Main Hill Logan, UT 84322{3900 CHARLES JOSEPH MINARD (1781-1870) And The Best Statistical Graphic Ever Drawn Citations: How others rate Minard's Flow Map of Napolean's Russian Campaign of 1812 . • \the best statistical graphic ever drawn" - (Tufte (1983), p. 40) • Etienne-Jules Marey said \it defies the pen of the historian in its brutal eloquence" -(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Joseph_Minard) • Howard Wainer nominated it as the \World's Champion Graph" - (Wainer (1997) - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Joseph_Minard) Brief background • Born on March 27, 1781. • His father taught him to read and write at age 4. • At age 6 he was taught a course on anatomy by a doctor. • Minard was highly interested in engineering, and at age 16 entered a school of engineering to begin his studies. • The first part of his career mostly consisted of teaching and working as a civil engineer. Gradually he became more research oriented and worked on private research thereafter. • By the end of his life, Minard believed he had been the co-inventor of the flow map technique. He wrote he was pleased \at having given birth in my old age to a useful idea..." - (Robinson (1967), p. 104) What was done before Minard? Examples: • Late 1700's: Mathematical and chemical graphs begin to appear. 1 • William Playfair's 1801:(Chart of the National Debt of England). { This line graph shows the increases and decreases of England's national debt from 1699 to 1800. -

Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861

UC Santa Barbara CSISS Classics Title Charles Joseph Minard, Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861. CSISS Classics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qj8h064 Author Corbett, John Publication Date 2001 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CSISS Classics - Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861 Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861 By John Corbett Background "It may well be the best statistical graphic ever drawn." Charles Joseph Minard's 1861 thematic map of Napoleon's ill-fated march on Moscow was thus described by Edward Tufte in his acclaimed 1983 book, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Of all the attempts to convey the futility of Napoleon's attempt to invade Russia and the utter destruction of his Grande Armee in the last months of 1812, no written work or painting presents such a compelling picture as does Minard's graphic. Charles Joseph Minard's Napoleon map, along with several dozen others that he published during his lifetime, set the standard for excellence in graphically depicting flows of people and goods in space, yet his role in the development of modern thematic mapping techniques is all too often overlooked. Minard was born in Dijon in 1781, and quickly gained a reputation as one of the leading French canal and harbor engineers of his time. In 1810, he was one of the first engineers to empty water trapped by cofferdams using relatively new steam-powered technology. In 1830 Minard began a long association with the prestigious École des Ponts et Chatussées, first as superintendent, and later as a professor and inspector. -

Theodor M. Porter Trust Un Numbers, 1995, Princeton

TRUST IN NUMBERS This page intentionally left blank TRUST IN NUMBERS THE PURSUIT OF OBJECTIVITY IN SCIENCE AND PUBLIC LIFE Theodore M. Porter PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON,NEW JERSEY Copyright 1995 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex All Rights Reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, Theodore, 1953– Trust in numbers : the pursuit of objectivity in science and public life / Theodore M. Porter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-691-03776-0 1. Science—Social aspects. 2. Objectivity. I. Title. Q175.5.P67 1995 306.4′5—dc20 94-21440 This book has been composed in Galliard Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources 13579108642 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xiii Introduction Cultures of Objectivity 3 PART I: POWER IN NUMBERS 9 Chapter One A World of Artifice 11 Chapter Two How Social Numbers Are Made Valid 33 Chapter Three Economic Measurement and the Values of Science 49 Chapter Four The Political Philosophy of Quantification 73 PART II: TECHNOLOGIES OF TRUST 87 Chapter Five Experts against Objectivity: Accountants and Actuaries 89 Chapter Six French State Engineers and the Ambiguities of Technocracy 114 Chapter Seven U.S. Army Engineers and the Rise of Cost-Benefit Analysis 148 PART III: POLITICAL AND SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITIES 191 Chapter Eight Objectivity and the Politics of Disciplines 193 Chapter Nine Is Science Made by Communities? 217 Notes 233 Bibliography 269 Index 303 This page intentionally left blank Preface SCIENCE is commonly regarded these days with a mixture of admiration and fear. -

The Fundamental Principles of Analytical Design

The Fundamental Principles ofAnalytical Design Categories such as time, space, cause, and number represent the most general relations which exist between things; surpassing all our other ideas in extension, they dominate all the details of our intellectual life. If humankind did not agree upon these essential ideas at every moment, if they did not have the same conception of time, space, cause, and number, all contact between their minds would be impossible . Emile Durk.heim, Les formes e/ementaires de Ia vie religieuse (Paris, 1912), 22-23. I do not paint things, I paint only the differences between things. Henri Matisse, Henri Matisse Dessins : themes et variations (Paris, 1943), 37· ExcELLENT graphics exemplify the deep fundamental principles of analytical design in action. If this were not the case, then something might well be wrong with the principles. Charles Joseph Minard's data-map describes the successive losses in men of the French army during the French invasion of Russia in 1812. Vivid historical content and brilliant design combine to make this one of the best statistical graphics ever. Carefully study Minard's graphic, At right, English translation of item 28 in shown in our English translation at right. A title announces the design Charles Joseph Minard, Tableaux Graphiques method (figurative map) and subject (what befell the French army in et Cartes Figuratives de M. Minard, 1845-186g, a portfolio of Minard's statistical maps at the Russia). Minard identifies himself and provides a credential. A paragraph Bibliotheque de !'Ecole Nationale des Pants of text explains the color code, the 3 scales of measurement, and the et Chaussees, Paris, 62 x 30 em, or 25 x 12 in. -

No Humble Pie: the Origins and Usage of a Statistical Chart

Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics Winter 2005, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 353–368 No Humble Pie: The Origins and Usage of a Statistical Chart Ian Spence University of Toronto William Playfair’s pie chart is more than 200 years old and yet its intellectual ori- gins remain obscure. The inspiration likely derived from the logic diagrams of Llull, Bruno, Leibniz, and Euler, which were familiar to William because of the instruction of his mathematician brother John. The pie chart is broadly popular but—despite its common appeal—most experts have not been seduced, and the academy has advised avoidance; nonetheless, the masses have chosen to ignore this advice. This commentary discusses the origins of the pie chart and the appro- priate uses of the form. Keywords: Bruno, circle chart, Euler, Leibniz, Llull, logic diagrams, pie chart, Playfair 1. Introduction The pie chart is more than two centuries old. The diagram first appeared (Playfair, 1801) as an element of two larger graphical displays (see Figure 1 for one instance) in The Statistical Breviary, whose charts portrayed the areas, populations, and rev- enues of European states. William Playfair had previously devised the bar chart and was first to advocate and popularize the use of the line graph to display time series in statistics (Playfair, 1786). The pie chart was his last major graphical invention. Playfair was an accomplished and talented adapter of the ideas of others, and although we may be confident that we know his sources of inspiration in the case of the bar chart and line graph, the intellectual motivations for the pie chart and its parent, the circle chart, remain obscure. -

A Brief History of Data Visualization

A Brief History of Data Visualization Michael Friendly Psychology Department and Statistical Consulting Service York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 in: Handbook of Computational Statistics: Data Visualization. See also BIBTEX entry below. BIBTEX: @InCollection{Friendly:06:hbook, author = {M. Friendly}, title = {A Brief History of Data Visualization}, year = {2006}, publisher = {Springer-Verlag}, address = {Heidelberg}, booktitle = {Handbook of Computational Statistics: Data Visualization}, volume = {III}, editor = {C. Chen and W. H\"ardle and A Unwin}, pages = {???--???}, note = {(In press)}, } © copyright by the author(s) document created on: March 21, 2006 created from file: hbook.tex cover page automatically created with CoverPage.sty (available at your favourite CTAN mirror) A brief history of data visualization Michael Friendly∗ March 21, 2006 Abstract It is common to think of statistical graphics and data visualization as relatively modern developments in statistics. In fact, the graphic representation of quantitative information has deep roots. These roots reach into the histories of the earliest map-making and visual depiction, and later into thematic cartography, statistics and statistical graphics, medicine, and other fields. Along the way, developments in technologies (printing, reproduction) mathematical theory and practice, and empirical observation and recording, enabled the wider use of graphics and new advances in form and content. This chapter provides an overview of the intellectual history of data visualization from medieval to modern times, describing and illustrating some significant advances along the way. It is based on a project, called the Milestones Project, to collect, catalog and document in one place the important developments in a wide range of areas and fields that led to mod- ern data visualization. -

Literacy Revolution: How the New Tools of Communication Change the Stories We Tell

Dominican Scholar Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects Student Scholarship 5-2017 Literacy Revolution: How the New Tools of Communication Change the Stories We Tell Molly Gamble Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2017.hum.04 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Gamble, Molly, "Literacy Revolution: How the New Tools of Communication Change the Stories We Tell" (2017). Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects. 282. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2017.hum.04 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LITERACY REVOLUTION: HOW THE NEW TOOLS OF COMMUNICATION CHANGE THE STORIES WE TELL A culminating thesis submitted to the faculty of Dominican University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Humanities by Molly Gamble San Rafael, California May 2017 © Copyright 2017 – by Molly Gamble All rights reserved ii Advisor’s Page This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor and approved by the Chair of the Master’s program, has been presented to and accepted by the faculty of the Humanities department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Humanities. The content and research methodologies presented in this work present the work of the candidate alone Molly Gamble- Candidate May 9, 2016 Joan Baranow, Ph.D- Graduate Humanities Program Director May 9, 2016 Leslie Ross, Ph.D- Primary Thesis Advisor May 9, 2016 Philip Novak, Ph.D- Secondary Thesis Advisor May 9, 2016 iii ABSTRACT The transmission of culture depends upon every generation reconsidering what it means to be literate. -

Introduction

Introduction Data graphics visually display measured (Fulltities by meam of the combined use of points, Jines, a coordinate system, numbers, symbols, words, shading, and color. The usc ofabstract, non-representational pictures to show numbers is a surprisingly recent invention, perhaps because of the diversity of skills required - the visual-artistic, empirical-statistical, and mathematical. It was not ullti11750-1Hoo that statistical graphics length and area to show quantity, time-series, scatterplots, and multivariate displays-were invented, long after such triumphs of mathematical ingenuity as logarithms, Cartesian coordinates, the calculus, and the basics of probability theory. The remarkable William Playfair (1759-1 H23) developed or improved upon nearly all the fundamental graphical designs, seeking to replace conven tional tables of numbers with the systematic visual representations of his "linear ari thmetic." Modern data graphics can do much more than simply substitute for small statistical tables. At their best, graphics arc instrumcnts for reasoning about quantitative inf(xmation. Often the most effec tive way to describe, explore, and summarize a set of l1umbers even a very large set-is to look at pictures of those numbers. Furthermore, of all mcthods for analyzing and communicating statistical information, well-designcd data graphics arc usually the simplest and at the same time the most powerful. The tlrst part of this book reviews the graphical practice of the two cellturies since Playfair. The reader will, I hope, rejoice in the graphical glories shown in Chapter 1 and then condemn the lapses and lost opportunities exhibited in Chapter 2. Chapter 3, 011 graph ical integrity and sophistication, seeks to account t(x these diftcr ences in quality of graphical design.