Revisions of Minard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unified Theory of Meaning Emergence Mike Taylor RN, MHA

The Unified Theory of Meaning Emergence Mike Taylor RN, MHA, CDE Author Unaffiliated Nursing Theorist [email protected] Member of the Board – Plexus Institute Specialist in Complexity and Health Lead designer – The Commons Project, a web based climate change intervention My nursing theory book, “Nursing, Complexity and the Science of Compassion”, is currently under consideration by Springer Publishing 1 Introduction Nursing science and theory is unique among the scientific disciplines with its emphasis on the human-environment relationship since the time of Florence Nightingale. An excellent review article in the Jan-Mar 2019 issue of Advances in Nursing Science, explores the range of nursing thought and theory from metaparadigms and grand theories to middle range theories and identifies a common theme. A Unitary Transformative Person-Environment-Health process is both the knowledge and the art of nursing. This type of conceptual framework is both compatible with and informed by complexity science and this theory restates the Human-Environment in a complexity science framework. This theory makes a two-fold contribution to the science of nursing and health, the first is in the consolidation and restatement of already successful applications of complexity theory to demonstrate commonalities in adaptive principles in all systems through a unified definition of process. Having a unified theoretical platform allows the application of the common process to extend current understanding and potentially open whole new areas for exploration and intervention. Secondly, the theory makes a significant contribution in tying together the mathematical and conceptual frameworks of complexity when most of the literature on complexity in health separate them (Krakauer, J., 2017). -

A Light in the Darkness: Florence Nightingale's Legacy

A Light in the Darkness: FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE’S LEGACY Florence Nightingale, a pioneer of nursing, was born on May 12, 1820. In celebration of her 200th birthday, the World Health Organization declared 2020 the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife.” It's now clear that nurses and health care providers of all kinds face extraordinary circumstances this year. Nightingale had a lasting influence on patient care that's apparent even today. Nightingale earned the nickname “the Lady with the Lamp” because she checked on patients at night, which was rare at the time and especially rare for head nurses to do. COURTESY OF THE WELLCOME COLLECTION When Florence Nightingale was growing up in England in the early 19th century, nursing was not yet a respected profession. It was a trade that involved little training. Women from upper-class families like hers were not expected to handle strangers’ bodily functions. She defied her family because she saw nursing as a calling. Beginning in 1854, Nightingale led a team of nurses in the Crimean War, stationed in present-day Turkey. She saw that the overcrowded, stuffy hospital with an overwhelmed sewer system was leading to high death rates. She wrote to newspapers back home, inspiring the construction of a new hospital. In celebration of: Brought to you by: Nightingale, who wrote several books on hospital and nursing practice, is often portrayed with a letter or writing materials. COURTESY OF THE WELLCOME COLLECTION A REVOLUTIONARY APPROACH After the war, Nightingale founded the Nightingale created Nightingale Training School at cutting-edge charts, like this one, which displayed the St. -

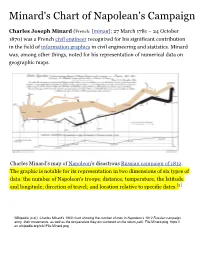

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

Time and Animation

TIME AND ANIMATION Petra Isenberg (&Pierre Dragicevic) TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION 2 TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION Time 3 VISUALIZATION OF TIME 4 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? 5 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? What data type is it? • Nominal? • Ordinal? • Quantitative? 6 TIME Ordinal Quantitative • Discrete • Continuous Aigner et al, 2011 7 TIME Joe Parry, 2007. Adapted from Mackinlay, 1986 8 TIME Periodicity • Natural: days, seasons • Social: working hours, holidays • Biological: circadian, etc. Has many subdivisions (units) • Years, months, days, weeks, H, M, S Has a specific meaning • Not captured by data type • Associations, conventions • Pervasive in the real-world • Time visualizations often considered as a separate type 9 TIME Shneiderman: • 1-dimensional data • 2-dimensional data • 3-dimensional data • temporal data • multi-dimensional data • tree data • network data 10 VISUALIZING TIME as a time point 11 VISUALIZING TIME as a time period 12 VISUALIZING TIME as a duration 13 VISUALIZING TIME PLUS DATA 14 MAPPING TIME TO SPACE 15 MAPPING TIME TO AN AXIS Time Data 16 TIME-SERIES DATA From a Statistics Book: • A set of observations xt, each one being recorded at a specific time t From Wikipedia: • A sequence of data points, measured typically at successive time instants spaced at uniform time intervals 17 LINE CHARTS Aigner et al, 2011 18 LINE CHARTS Marey’s Physiological Recordings Plethysmograph Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) Pneumogram Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) 19 LINE CHARTS Pendulum Seismometer (image source) Andrea Bina, 1751 Possibly also 17th century (source) 20 LINE CHARTS Inclinations of planetary orbits Macrobius, 10th or 11th century cited in Kendall, 1990 21 Marey’s Train Schedule LINE CHARTS 6 PARIS LYON 7 22 Étienne-Jules Marey, 1885, cited in Tufte, 1983 OTHER CHARTS Line Plots Point Plots Silhouette Graphs Bar Charts Aigner et al, 2011 23 OTHER CHARTS Combination - New York Times Weather Chart New York Times, 1980. -

An African 'Florence Nightingale' a Biography

An African 'Florence Nightingale' a biography of: Chief (Dr) Mrs Kofoworola Abeni Pratt OFR, Hon. LLD (Ife), Teacher's Dip., SRN, SCM, Ward Sisters' Cert., Nursing Admin. Cert., FWACN, Hon. FRCN, OSTJ, Florence Nightingale Medal by Dr Justus A. Akinsanya, B.Sc. (Hons) London, Ph.D. (London) Reader in Nursing Studies Dorset Institute of Higher Education, U.K. VANTAGE PUBLISHERS' LTD. IBADAN, NIGERIA Table of Contents © Dr Justus A. Akinsanya 1987 All rights reserved. Acknowledgements lX No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans Preface Xl mitted, in any formor by any means, without prior per mission from the publishers. CHAPTERS I. The Early Years 1 First published 1987 2. Marriage and Family Life 12 3. The Teaching Profession 26 4. The Nursing Profession 39 Published by 5. Life at St Thomas' 55 VANTAGE PUBLISHERS (INT.) LTD., 6. Establishing a Base for a 98A Old Ibadan Airport, Career in Nursing 69 P. 0. Box 7669, 7. The University College Hospital, Secretariat, Ibadan-Nigeria's Premier Hospital 79 Ibadan. 8. Progress in Nursing: Development of Higher Education for Nigerian Nurses 105 9. Towards a Better Future for 123 ISBN 978 2458 18 X (limp edition) Nursing in Nigeria 145 ISBN 978 2458 26 0 (hardback edition) 10. Professional Nursing in Nigeria 11. A Lady in Politics 163 12. KofoworolaAbeni - a Lady of many parts 182 Printed by Adeyemi Press Ltd., Ijebu-Ife, Nigeria. Appendix 212 Index 217 Dedicated to the memory of the late Dr Olu Pratt Acknowledge1nents It is difficult in a few lines to thank all those who have contributed to this biography. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

The Forgotten Discovery of Gravity Models and the Inefficiency of Early

The forgotten discovery of gravity models and the inefficiency of early railway networks Andrew Odlyzko School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA [email protected] http://www.dtc.umn.edu/∼odlyzko Revised version, April 19, 2015 Abstract. The routes of early railways around the world were generally inef- ficient because of the incorrect assumption that long distance travel between major cities would dominate. Modern planners rely on methods such as the “gravity models of spatial interaction,” which show quantitatively the impor- tance of accommodating travel demands between smaller cities. Such models were not used in the 19th century. This paper shows that gravity models were discovered in 1846, a dozen years earlier than had been known previously. That discovery was published during the great Railway Mania in Britain. Had the validity and value of gravity models been recognized properly, the investment losses of that gigantic bubble could have been lessened, and more efficient rail systems in Britain and many other countries would have been built. This incident shows society’s early encounter with the “Big Data” of the day and the slow diffusion of economically significant information. The results of this study suggest that it will be increasingly feasible to use modern network science to analyze information dissemination in the 19th century. That might assist in understanding the diffusion of technologies and the origins of bubbles. Keywords: gravity models, railway planning, diffusion of information JEL classification codes: D8, L9, N7 1 Introduction Dramatic innovations in transportation or communication frequently produce predictions that distance is becoming irrelevant. In recent decades, two popular books in this genre introduced the concepts of “death of distance” [7] and “the Earth is flat” [25]. -

Elizabeth F. Lewis Phd Thesis

PETER GUTHRIE TAIT NEW INSIGHTS INTO ASPECTS OF HIS LIFE AND WORK; AND ASSOCIATED TOPICS IN THE HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS Elizabeth Faith Lewis A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6330 This item is protected by original copyright PETER GUTHRIE TAIT NEW INSIGHTS INTO ASPECTS OF HIS LIFE AND WORK; AND ASSOCIATED TOPICS IN THE HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS ELIZABETH FAITH LEWIS This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Ph.D. at the University of St Andrews. 2014 1. Candidate's declarations: I, Elizabeth Faith Lewis, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 59,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in September 2010; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2014. Signature of candidate ...................................... Date .................... 2. Supervisor's declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard

Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard Michael Friendly Psychology Department and Statistical Consulting Service York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 in: Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. See also BIBTEX entry below. BIBTEX: @Article{ Friendly:02:Minard, author = {Michael Friendly}, title = {Visions and {Re-Visions} of {Charles Joseph Minard}}, year = {2002}, journal = {Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics}, volume = {27}, number = {1}, pages = {31--51}, } © copyright by the author(s) document created on: February 19, 2007 created from file: jebs.tex cover page automatically created with CoverPage.sty (available at your favourite CTAN mirror) JEBS, 2002, 27(1), 31–51 Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard∗ Michael Friendly York University Abstract Charles Joseph Minard is most widely known for a single work, his poignant flow-map depiction of the fate of Napoleon’s Grand Army in the disasterous 1812 Russian campaign. In fact, Minard was a true pioneer in thematic cartography and in statistical graphics; he developed many novel graphics forms to depict data, always with the goal to let the data “speak to the eyes.” This paper reviews Minard’s contributions to statistical graphics, the time course of his work, and some background behind the famous March on Moscow graphic. We also look at some modern re-visions of this graph from an information visualization perspecitive, and examine some lessons this graphic provides as a test case for the power and expressiveness of computer systems or languages for graphic information display and visual- ization. Key words: Statistical graphics; Data visualization, history; Napoleonic wars; Thematic car- tography; Dynamic graphics; Mathematica 1 Introduction RE-VISION n. -

Facts About Florence Nightingale

FACTS ABOUT FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE • Born in Florence, Italy, on May 12th, 1820 (named for the city) to an affluent British family • Nightingale was active in philanthropy as a child, and believed nursing to be her “divine purpose” (Biography.com, Background and early life section). NURSING EDUCATION AND BEGINNING CAREER • Enrolled at the nursing program at the Institution of Protestant Deaconesses in Kaiserswerth, Germany in 1850-1851. • Found employment at the Harley Street hospital as a nurse, and was soon promoted to superintendent all in 1853 (Biography.com, Background and early life section). • Her parents viewed her career choice as unwise, given her social position and the expectation that she might “marry a man of means to ensure her class standing.” DID YOU KNOW? Nightingale was a prodigious and versatile writer. She was also a pioneer in data visualization with the use of infographics, effectively using graphical presentations of statistical data. (Bostridge, Mark, 17 February 2011) Painting of Nightingale by Photograph of Nightingale Augustus Egg, c. 1840s by Kilburn, c. 1854 CRIMEAN WAR • In October 1853, the Crimean War broke out between the Turks and Russia, which eventually involved England and France in the spring of 1854. As the English and French sent their troops to Turkey as allies, there was a need for a mobile nursing unit to accompany them and handle the outbreaks of cholera, dysentery, and other serious disorders – as well as treat those who had succumbed to battle injuries. • Florence Nightingale was asked to lead a volunteer group of nurses to Scutari, which was the Greek name for a district in Istanbul. -

Florence Nightingale's Legacy: Caring, Compassion, Health, and Healing

Florence Nightingale’s Legacy: Caring, Compassion, Health, and Healing Across Cultures for the 21st Century — Local to Global Barbara Dossey, PhD, RN, AHN-BC, FAAN, HWNC-BC Director, International Nurse Coach Association (INCA) International Co-Director, Nightingale Initiative for Global Health (NIGH) September 29, 2017 14th Annual Caring Across Cultures Conference Kramer School of Nursing Oklahoma City University, Oklahoma Objectives 1. Explore Florence Nightingale’s legacy (1820-1910) of caring, compassion, healing, and advocacy across cultures for 21st– century nursing and healthcare—local to global. 2. Discuss the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and relevance for nurses, Interprofessional colleagues, and concerned citizens. 3. Explore ANA’s Healthy Nurse Healthy NationTM Grand Challenge and the five domains. 4. Examine the Theory of Integral Nursing and the integral, holistic and integrative paradigms and application for a healthy world. 5. Examine the Integrative Health and Wellness Assessment (IHWA). 6. Explore your ‘Reason for Being’. Source: http://www.nighvision.net/why-nigh-why-now.html Objective 1: Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) Legacy Frances Nightingale with daughters Florence (in lap, age 4) and Parthe (age 6) © 1824) Photo Source: National Trust London William Edward Nightingale © 1870 Source: Courtauld Institute Gallery, London Florence, age 19, seated Parthe, age 21, standing © 1839 Source: National Portrait Gallery London Florence, age 15, right & Aunt Mai Smith, leaning with her two daughters.© 1835 Photo Source; Hampshire County Record Office, Winchester, UK Lea Hurst, Derbyshire, England Nightingale summer home Photo Source: Barbara Dossey Embley Park, Romsey, Hampshire, England Nightingale main residence Photo Source: Barbara Dossey At 17, Nightingale heard a ‘call from God’ to ‘become a nurse’ while sitting under the Cedars of Lebanon at Embley Park Photo Source: Barbara Dossey Richard Monckton Milnes, age 33 © 1842 Photo Source: National Portrait Gallery London She was much more than the Nightingale we thought we knew. -

Public Recognition and Media Coverage of Mathematical Achievements

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 9 | Issue 2 July 2019 Public Recognition and Media Coverage of Mathematical Achievements Juan Matías Sepulcre University of Alicante Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Sepulcre, J. "Public Recognition and Media Coverage of Mathematical Achievements," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 9 Issue 2 (July 2019), pages 93-129. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.201902.08 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol9/iss2/8 ©2019 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Public Recognition and Media Coverage of Mathematical Achievements Juan Matías Sepulcre Department of Mathematics, University of Alicante, Alicante, SPAIN [email protected] Synopsis This report aims to convince readers that there are clear indications that society is increasingly taking a greater interest in science and particularly in mathemat- ics, and thus society in general has come to recognise, through different awards, privileges, and distinctions, the work of many mathematicians.