Innovation in the Vine Sector: the Champagne Region Invents the Grape Varieties of Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Breeding Efforts in Salt‐And Drought-Tolerant Rootstocks –

12/12/2017 Current Breeding Efforts in Salt‐and Drought-Tolerant Rootstocks – Andy Walker ([email protected]) California Grape Rootstock Improvement Commission / California Grape Rootstock Research Foundation CDFA NT, FT, GV Improvement Advisory Board California Table Grape Commission American Vineyard Foundation E&J Gallo Winery Louise Rossi Endowed Chair in Viticulture Rootstock Breeding Objectives • Develop better forms of drought and salinity tolerance • Combine these tolerances with broad nematode resistance and high levels of phylloxera resistance • Develop better fanleaf degeneration tolerant rootstocks • Develop rootstocks with “Red Leaf” virus tolerance 1 12/12/2017 V. riparia Missouri River V. rupestris Jack Fork River, MO 2 12/12/2017 V. berlandieri Fredericksburg, TX Which rootstock to choose? • riparia based – shallow roots, water sensitive, low vigor, early maturity: – 5C, 101-14, 16161C (3309C) • rupestris based – broadly distributed roots, relatively drought tolerant, moderate to high vigor, midseason maturity: – St. George, 1103P, AXR#1 (3309C) 3 12/12/2017 Which rootstock to choose? • berlandieri based – deeper roots, drought tolerant, higher vigor, delayed maturity: – 110R, 140Ru (420A, 5BB) • champinii based – deeper roots, drought tolerant, salt tolerance, but variable in hybrids – Dog Ridge, Ramsey (Salt Creek) – Freedom, Harmony, GRNs • Site trumps all… soil depth, rainfall, soil texture, water table V. monticola V. candicans 4 12/12/2017 CP‐SSR LN33 1613-59 V. riparia x V. rupestris Couderc 1613 14 markers 22 haplotypes Harmony Freedom V. berlandieri x V. riparia Couderc 1616 Ramsey Vitis rupestris cv Witchita refuge V. berlandieri x V. rupestris 157-11 (Couderc) 3306 (Couderc) V. berlandieri x V. vinifera 3309 (Couderc) Vitis riparia cv. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Growing Grapes in Missouri

MS-29 June 2003 GrowingGrowing GrapesGrapes inin MissouriMissouri State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University-Mountain Grove Growing Grapes in Missouri Editors: Patrick Byers, et al. State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University Department of Fruit Science 9740 Red Spring Road Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711-2999 http://mtngrv.missouristate.edu/ The Authors John D. Avery Patrick L. Byers Susanne F. Howard Martin L. Kaps Laszlo G. Kovacs James F. Moore, Jr. Marilyn B. Odneal Wenping Qiu José L. Saenz Suzanne R. Teghtmeyer Howard G. Townsend Daniel E. Waldstein Manuscript Preparation and Layout Pamela A. Mayer The authors thank Sonny McMurtrey and Katie Gill, Missouri grape growers, for their critical reading of the manuscript. Cover photograph cv. Norton by Patrick Byers. The viticulture advisory program at the Missouri State University, Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center offers a wide range of services to Missouri grape growers. For further informa- tion or to arrange a consultation, contact the Viticulture Advisor at the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center, 9740 Red Spring Road, Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711- 2999; telephone 417.547.7508; or email the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center at [email protected]. Information is also available at the website http://www.mvec-usa.org Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Considerations in Planning a Vineyard ........................................................ -

Evaluating Resistance to Grape Phylloxera in Vitis Species with an in Vitro Dual Culture Assay WLADYSLAWA GRZEGORCZYK ~ and M

Evaluating Resistance to Grape Phylloxera in Vitis Species with an in vitro Dual Culture Assay WLADYSLAWA GRZEGORCZYK ~ and M. ANDREW WALKER 2. Forty-one accessions of 12 Vitis L. and Muscadinia Small species were evaluated for resistance to grape phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae Fitch) using an in vitro dual culture system. The performance of the species tested in this study was consistent with previously published studies with whole plants and helps confirm the utility of in vitro dual culture for the study of grape/phylloxera interactions. This in vitro system provides rapid results (8 wk) and the ability to observe the phylloxera/grape interaction without interference from other factors. This system also provides an evaluation that overemphasizes susceptibility, thus providing more confidence in the resistance responses of a given species or accession. Among the unusual responses were the susceptibility of V. riparia Michx. DVIT 1411; susceptibility within V. berlandieri Planch.; relatively wide ranging responses in V. rupestris Scheele; and the lack of feeding on the roots of V. califomica Benth., in contrast to the severe foliar feeding damage that occurred on this species. Vitis califomica #11 and V. girdiana Munson DVIT 1379 were unusual because phylloxera on them had the shortest generation times. Such accessions might be used to examine how grape hosts influence phylloxera behavior. Very strong resistance was found within V. aestivalisMichx. DVIT 7109 and 7110; I/. berlandieric9031; V. cinereaEngelm; I/. riparia (excluding DVIT 1411 ); V. rupestris DVIT 1418 and 1419; and M. rotundifolia Small. These species and accessions seem to possess enough resistance to enable their use in breeding with minimal concern about phylloxera susceptibility. -

Climate Change Adaptation in the Champagne Region

CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION IN THE CHAMPAGNE REGION PRESS PACK – JUNE 2019 Contents P. 3 THE CHALLENGE POSED BY CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAMPAGNE P. 4 CHAMPAGNE’S CARBON FOOTPRINT P. 7 A PROGRAMME TO DEVELOP NEW GRAPE VARIETIES P. 10 VINE TRAINING P. 11 OENOLOGICAL PRACTICES P. 13 A REGION COMMITTED TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT P. 14 SUSTAINABLE VITICULTURE CERTIFICATION IN CHAMPAGNE THE CHALLENGE POSED BY CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAMPAGNE GLOBAL WARMING IS A FACT. THE GLOBAL AVERAGE TEMPERATURE HAS INCREASED BY 0.8°C SINCE PRE-INDUSTRIAL TIMES. THE IMPACT CAN ALREADY BE SEEN IN CHAMPAGNE. CLIMATE CHANGE A REALITY IN THE REGION Over the past 30 years, the three key uni- versal bioclimatic indexes used to monitor Water balance local winegrowing conditions have evolved slightly down as follows: Huglin index rose from 1,565 to 1,800 Cool nights index rose from 9.8°C to 10.4°C Compared with the 30-year baseline average (1961-1990), the temperature has risen by 1.1°C ON AVERAGE. Average rainfall is still 700mm/year. Damage caused by spring frosts has slightly increased despite a drop in the number of frosty nights due to earlier bud burst. The consequences are already visible and are indeed positive for the quality of the musts: Over the past 30 years: - 1,3 g H2SO4/l total acidity Earlier harvests starting 18 days earlier + 0,7 % vol natural alcoholic strength by volume These beneficial effects may well continue if global warming is limited to a 2°C rise. However, the Champagne Region is now exploring ideas that would enable the inherent characteristics of its wines to be preserved in less optimistic climate change scenarios. -

Protecting South Australia from the Phylloxera Threat

The Phylloxera Fight Protecting South Australia from the phylloxera threat Wally Boehm Winetitles Adelaide 1996 in association with The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia First published in 1996 by Winetitles PO Box 1140 Marleston SA 5033 A USTR A LI A in association with The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia 25 Grenfell Street, Adelaide South Australia 5000 © Copyright 1996 Wally Boehm and The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Boehm, E.W. (Ernest Walter). The phylloxera fight: protecting South Australia from the phylloxera threat. Includes index. ISBN 1 875130 21 7 1. Phylloxera – South Australia. 2. Grapes – Diseases and pests – South Australia. 3. Grapes – Diseases and pests – Control – South Australia. I. South Australia. Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board. II. Title 634.82752099423 Design and typesetting Michael Deves Printed and bound by Hyde Park Press CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 The Dread of Phylloxera 1 CHAPTER 2 Phylloxera in Australia 13 CHAPTER 3 Phylloxera Legislation 34 CHAPTER 4 Rootstocks and Virus 45 CHAPTER 5 Nurseries and New Varieties 53 CHAPTER 6 Biotypes 58 CHAPTER 7 Vine Introduction Procedure 62 APPENDIX 1 The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Act 1994 71 APPENDIX 2 Vine Variety Introductions to South Australia 75 INDEX 90 Record of Board Membership Chairmen District 2 O.B. SEPPELT 1926–1933 O.B. Seppelt 1926–1933 Keith Leon RAINSFORD 1933–1944 Friedrich William Gursansky 1933–1955 Frederick Walter KAY 1944–1947 O.S. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Vitaceae Based on Plastid Sequence Data

PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF VITACEAE BASED ON PLASTID SEQUENCE DATA by PAUL NAUDE Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER SCIENTAE in BOTANY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: DR. M. VAN DER BANK December 2005 I declare that this dissertation has been composed by myself and the work contained within, unless otherwise stated, is my own Paul Naude (December 2005) TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Abstract iii Index of Figures iv Index of Tables vii Author Abbreviations viii Acknowledgements ix CHAPTER 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Vitaceae 1 1.2 Genera of Vitaceae 6 1.2.1 Vitis 6 1.2.2 Cayratia 7 1.2.3 Cissus 8 1.2.4 Cyphostemma 9 1.2.5 Clematocissus 9 1.2.6 Ampelopsis 10 1.2.7 Ampelocissus 11 1.2.8 Parthenocissus 11 1.2.9 Rhoicissus 12 1.2.10 Tetrastigma 13 1.3 The genus Leea 13 1.4 Previous taxonomic studies on Vitaceae 14 1.5 Main objectives 18 CHAPTER 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS 21 2.1 DNA extraction and purification 21 2.2 Primer trail 21 2.3 PCR amplification 21 2.4 Cycle sequencing 22 2.5 Sequence alignment 22 2.6 Sequencing analysis 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 3 RESULTS 32 3.1 Results from primer trail 32 3.2 Statistical results 32 3.3 Plastid region results 34 3.3.1 rpL 16 34 3.3.2 accD-psa1 34 3.3.3 rbcL 34 3.3.4 trnL-F 34 3.3.5 Combined data 34 CHAPTER 4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 42 4.1 Molecular evolution 42 4.2 Morphological characters 42 4.3 Previous taxonomic studies 45 4.4 Conclusions 46 CHAPTER 5 REFERENCES 48 APPENDIX STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF DATA 59 ii ABSTRACT Five plastid regions as source for phylogenetic information were used to investigate the relationships among ten genera of Vitaceae. -

Wine Grape Terminology- the Lingo of Viticulture

Wine Grape Terminology- The Lingo of Viticulture Dr. Duke Elsner Small Fruit Educator Michigan State University Extension Traverse City, Michigan 2014 Wine Grape Vineyard Establishment Conference Viticulture Terminology Where to start? How far to go? – Until my time runs out! What are grapes? “…thornless, dark-stemmed, green- flowered, mostly shreddy-barked, high-climbing vines that climb by means of tendrils.” Cultivated species of grapes Vitis labrusca – Native to North America – Procumbent shoot growth habit – Concord, Niagara, dozens more Vitis vinifera – Eastern Europe, middle east – Upright shoot growth habit – Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Gewurztraminer, etc. Other important species of grapes Vitis aestivalis Summer grape Vitis riparia Riverbank grape Vitis rupestris Sand grape Vitis rotundifolia Muscadine grape Vitis cinerea Winter grape Variety A varient form of a wild plant that has been recognized as a true taxon ranking below sub- species. Cultivar A variety of a plant species originating and continuing in cultivation and given a name in modern language. Hybrid Cultivar A new cultivar resulting from the intentional crossing of selected cultivars, varieties or species. Hybrid Cultivar A new cultivar resulting from the intentional crossing of selected cultivars, varieties or species. Clone (clonal selection) A strain of grape cultivar that has been derived by asexual reproduction and presumably has a desirable characteristic that sets it apart from the “parent” variety. Pinot Noir = cultivar Pinot Noir Pommard = clone Grafted vine A vine produced by a “surgical” procedure that connects one or more desired fruiting cultivars onto a variety with desired root characteristics. Scion Above-graft part of a grafted vine, including leaf and fruit-bearing parts. -

Grape Varieties for Indiana

Commercial • HO-221-W Grape Varieties for Indiana COMMERCIAL HORTICULTURE • DEPARTMENT OF HORTICULTURE PURDUE UNIVERSITY COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE • WEST LAFAYETTE, IN Bruce Bordelon Selection of the proper variety is a major factor for fungal diseases than that of Concord (Table 1). Catawba successful grape production in Indiana. Properly match- also experiences foliar injury where ozone pollution ing the variety to the climate of the vineyard site is occurs. This grape is used primarily in white or pink necessary for consistent production of high quality dessert wines, but it is also used for juice production and grapes. Grape varieties fall into one of three groups: fresh market sales. This grape was widely grown in the American, French-American hybrids, and European. Cincinnati area during the mid-1800’s. Within each group are types suited for juice and wine or for fresh consumption. American and French-American Niagara is a floral, strongly labrusca flavored white grape hybrid varieties are suitable for production in Indiana. used for juice, wine, and fresh consumption. It ranks The European, or vinifera varieties, generally lack the below Concord in cold hardiness and ripens somewhat necessary cold hardiness to be successfully grown in earlier. On favorable sites, yields can equal or surpass Indiana except on the very best sites. those of Concord. Acidity is lower than for most other American varieties. The first section of this publication discusses American, French-American hybrids, and European varieties of wine Other American Varieties grapes. The second section discusses seeded and seedless table grape varieties. Included are tables on the best adapted varieties for Indiana and their relative Delaware is an early-ripening red variety with small berries, small clusters, and a mild American flavor. -

Differences in Grape Phylloxera-Related Grapevine Root

PLANT PATHOLOGY HORTSCIENCE 34(6):1108–1111. 1999. ing vineyards may result in reduced phyllox- era numbers and phylloxera-related damage. The purpose of this work was to determine Differences in Grape Phylloxera- whether differences in phylloxera populations or phylloxera-related damage could be attrib- related Grapevine Root Damage in uted to organic or conventional management Organically and Conventionally regimes. Materials and Methods Managed Vineyards in California Two types of long-term vineyard manage- ment regimes were compared, organic and D.W. Lotter, J. Granett, and A.D. Omer conventional. Organically managed vineyards Department of Entomology, University of California, One Shields Avenue, (OMV) chosen for study were certified by the Davis, CA 95616-8584 California Certified Organic Farmers program (Santa Cruz) and were characterized by the Additional index words. Vitis vinifera, Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, organic farming, sustain- use of cover crops and composts and no syn- able agriculture, soil suppressiveness, Trichoderma thetic fertilizers or pesticides. Vineyards that had been organically certified for at least 5 Abstract. Secondary infection of roots by fungal pathogens is a primary cause of vine years and were infested with phylloxera were damage in phylloxera-infested grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.). In summer and fall surveys selected for this study. The time threshold of 5 in 1997 and 1998, grapevine root samples were taken from organically (OMVs) and years of organic management was chosen based conventionally managed vineyards (CMVs), all of which were phylloxera-infested. In both on experiences of organic farmers, consult- years, root samples from OMVs showed significantly less root necrosis caused by fungal ants, and researchers indicating that the full pathogens than did samples from CMVs, averaging 9% in OMVs vs. -

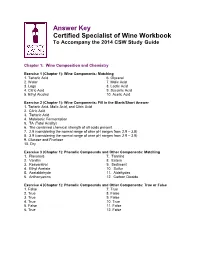

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Olivier Horiot Profile

Olivier Horiot Profile In the southern-most part of the Champagne region, the Côte des Bar in the Aube department, there is the town of Les Riceys, where the slopes are blessed with the portlandian formation of Kimmeridgian chalk, that same great stuff that is the foundation of the finest Chablis and Sancerre. Except here the idea was to plant Pinot Noir on these chalky slopes, do a long maceration, often using whole bunches, and then age it a few years (at least 3) before release -- not exactly your average deck wine. Olivier Horiot took over the estate of his father Serge in 1999; though it bears his name due to inheritance, his wife Marie is essential to day to day operations and runs the cellar. They immediately started using organic and some biodynamic practices, as well as highlighting specific parcels in the effort of being more terroir-focused. In order to make the Rosé des Riceys, the Horiot do a very strict selection of grapes from two separate sites - en Valingrain and en Barmont - vinifying them separately. The wines start with about 10% of the grapes foot-trodden at the bottom of the cuve, then whole bunches are added. Macerations usually last 5-6 days, with pumping over twice a day. After the wine is racked into older barrels, it remains there for a few years before being bottled without fining or filtration. The Horiot also produce 4 Champagnes: a Blanc de Noir from the en Barmont site named Sève, two blends of multiple parcels, 5 Sens and Métisse, as well as a quirky, unexpected Champagne produced with the Arbane grape, aptly named Arbane.