Innovations Involved in Champagne Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents White Red Other 2020 2019 2018 2017

2020 LIST Table of Contents 2019 Wines by the Glass .........................................................................................................1 Small Format Listings - Red & White ................................................................................2 White Champagne / Sparkling Wine ......................................................................................... 3 Sparkling Wine / Riesling / Rosé / Pinot Gris (Grigio) ....................................................... 4 Chardonnay / Sauvignon Blanc ....................................................................................... 5 Chardonnay ................................................................................................................. 6 2018 Interesting White Varietals / White Blends ...................................................................... 7 Red Pinot Noir .....................................................................................................................8 Pinot Noir / Merlot / Malbec / Zinfandel .........................................................................9 Syrah / Petite Syrah / Shiraz / New World Blends ............................................................ 10 Cabernet Sauvignon / Cabernet Sauvignon Blends ............................................................ 11 Cabernet Sauvignon / Cabernet Sauvignon Blends ............................................................ 12 Cabernet Sauvignon / Cabernet Franc / Italy .................................................................. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Chardonnay Educator Guide

CHARDONNAY EDUCATOR GUIDE AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED PREPARING FOR YOUR CLASS THE MATERIALS VIDEOS As an educator, you have access to a suite of teaching resources and handouts, You will find complementary video including this educator guide: files for each program in the Wine Australia Assets Gallery. EDUCATOR GUIDE We recommend downloading these This guide gives you detailed topic videos to your computer before your information, as well as tips on how to best event. Look for the video icon for facilitate your class and tasting. It’s a guide recommended viewing times. only – you can tailor what you teach to Loop videos suit your audience and time allocation. These videos are designed to be To give you more flexibility, the following played in the background as you optional sections are flagged throughout welcome people into your class, this document: during a break, or during an event. There is no speaking, just background ADVANCED music. Music can be played aloud, NOTES or turned to mute. Loop videos should Optional teaching sections covering be played in ‘loop’ or ‘repeat’ mode, more complex material. which means they play continuously until you press stop. This is typically an easily-adjustable setting in your chosen media player. COMPLEMENTARY READING Feature videos These videos provide topical insights Optional stories that add from Australian winemakers, experts background and colour to the topic. and other. Feature videos should be played while your class is seated, with the sound turned on and SUGGESTED clearly audible. DISCUSSION POINTS To encourage interaction, we’ve included some optional discussion points you may like to raise with your class. -

Climate Change Adaptation in the Champagne Region

CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION IN THE CHAMPAGNE REGION PRESS PACK – JUNE 2019 Contents P. 3 THE CHALLENGE POSED BY CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAMPAGNE P. 4 CHAMPAGNE’S CARBON FOOTPRINT P. 7 A PROGRAMME TO DEVELOP NEW GRAPE VARIETIES P. 10 VINE TRAINING P. 11 OENOLOGICAL PRACTICES P. 13 A REGION COMMITTED TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT P. 14 SUSTAINABLE VITICULTURE CERTIFICATION IN CHAMPAGNE THE CHALLENGE POSED BY CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAMPAGNE GLOBAL WARMING IS A FACT. THE GLOBAL AVERAGE TEMPERATURE HAS INCREASED BY 0.8°C SINCE PRE-INDUSTRIAL TIMES. THE IMPACT CAN ALREADY BE SEEN IN CHAMPAGNE. CLIMATE CHANGE A REALITY IN THE REGION Over the past 30 years, the three key uni- versal bioclimatic indexes used to monitor Water balance local winegrowing conditions have evolved slightly down as follows: Huglin index rose from 1,565 to 1,800 Cool nights index rose from 9.8°C to 10.4°C Compared with the 30-year baseline average (1961-1990), the temperature has risen by 1.1°C ON AVERAGE. Average rainfall is still 700mm/year. Damage caused by spring frosts has slightly increased despite a drop in the number of frosty nights due to earlier bud burst. The consequences are already visible and are indeed positive for the quality of the musts: Over the past 30 years: - 1,3 g H2SO4/l total acidity Earlier harvests starting 18 days earlier + 0,7 % vol natural alcoholic strength by volume These beneficial effects may well continue if global warming is limited to a 2°C rise. However, the Champagne Region is now exploring ideas that would enable the inherent characteristics of its wines to be preserved in less optimistic climate change scenarios. -

Protecting South Australia from the Phylloxera Threat

The Phylloxera Fight Protecting South Australia from the phylloxera threat Wally Boehm Winetitles Adelaide 1996 in association with The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia First published in 1996 by Winetitles PO Box 1140 Marleston SA 5033 A USTR A LI A in association with The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia 25 Grenfell Street, Adelaide South Australia 5000 © Copyright 1996 Wally Boehm and The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Boehm, E.W. (Ernest Walter). The phylloxera fight: protecting South Australia from the phylloxera threat. Includes index. ISBN 1 875130 21 7 1. Phylloxera – South Australia. 2. Grapes – Diseases and pests – South Australia. 3. Grapes – Diseases and pests – Control – South Australia. I. South Australia. Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board. II. Title 634.82752099423 Design and typesetting Michael Deves Printed and bound by Hyde Park Press CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 The Dread of Phylloxera 1 CHAPTER 2 Phylloxera in Australia 13 CHAPTER 3 Phylloxera Legislation 34 CHAPTER 4 Rootstocks and Virus 45 CHAPTER 5 Nurseries and New Varieties 53 CHAPTER 6 Biotypes 58 CHAPTER 7 Vine Introduction Procedure 62 APPENDIX 1 The Phylloxera and Grape Industry Act 1994 71 APPENDIX 2 Vine Variety Introductions to South Australia 75 INDEX 90 Record of Board Membership Chairmen District 2 O.B. SEPPELT 1926–1933 O.B. Seppelt 1926–1933 Keith Leon RAINSFORD 1933–1944 Friedrich William Gursansky 1933–1955 Frederick Walter KAY 1944–1947 O.S. -

Stories from the Vineyard $80

As with Chef Crenn’s menus, which are inspired by her travels, so too is the beverage program where we seek out selections from the world at large. Petit Crenn proudly presents a wine pairing that is an opportunity to sit back and relax while exploring the world via the senses. Take a trip in our hospitable hands. STORIES FROM THE VINEYARD $80 A focused yet whimsical wine pairing that dives into many pockets of the world that concentrates on the roots of Petit Crenn: France and California. A sense of place and ethos. A connection with both the fruit and the farmer. This is an excellent opportunity to enjoy something unexpected, and visit hidden gems of classic wine regions. This evening we welcome you to be a part of Petit Crenn’s wine infinity. Wine Director Mikayla Cohen A service included beverage experience. BY THE GLASS SPARKLING NV Désiré Petit, Brut Rosé, Pinot Noir, Crémant du Jura 18 NV Gaston Chiquet, Brut Rosé, 1er Cru, Champagne 30 NV Lancelot-Royer, Blanc de Blancs, Grand Cru, Champagne 25 WHITE 2018 Hourglass, Sauvignon Blanc, ‘Estate,’ Calistoga 20 2015 Kunin, Chenin Blanc, ‘Jurassic Park,’ Santa Ynez Valley 18 2016 Hirtzberger, Weissburgunder Smaragd, ‘Steinporz,’ Wachau 28 2017 Pierre Yves Colin-Morey, ‘Les Cailloux,’ Rully, Burgundy 35 ROSÉ 2018 Arnot-Roberts, Touriga Nacional/Tinta Cao, North Coast 15 2017 Domaine de Terrebrune, Bandol, Provence 20 RED 2018 Combe, Trousseau, ‘Stolpman,’ Ballard Canyon 18 2017 Occidental, Pinot Noir, ‘Freestone,’ West Sonoma Coast 35 2016 Vieux Télégraphe, ‘Télégramme,’ Châteaneuf-du-Pape 28 A service included beverage experience. -

Reserve Wines by the Glass Served Tableside Via Coravin

Reserve Wines By The Glass Served Tableside via Coravin WHITES & ROSÉS ASSYRTIKO, Domaine Sigalas, Santorini, Greece, 2013 ....................................................... 11 Grown on the volcanic soils of the island of Santorini, assyrtiko is truly a pleasure to drink. Grown in a basket style with the grapes in the center to protect from the vicious winds, the wine is acid driven with loads of minerality and personality; this a wine to try is you love dry riesling or sauvignon blanc. CHARDONNAY, Cakebread, Napa Valley, California, 2012 ........................................................ 20 CHARDONNAY, Domaine Savary, Chablis, Burgundy, France, 2012 ...................................... 13.75 ROSÉ, Bellwether Wine Cellars, “Vin Gris,” Finger Lakes, New York, 2013 ...................... 13 Bellwether Wine Cellars winemaker Kris Matthewson was just called a “rockstar” in the New York Times and this wine, along with his wonderful dry riesling and pinot noir, shows why. A vin gris, or “grey wine”—a white wine made from red grapes—this is more akin to dry rose than white wine. Natural winemaking at its finest, with no unnecessary additives or intervention, Bellwether continues to be a leader of geeky winemaking in the Finger Lakes, and shows what the region can do with passionate people always pushing the boundaries. SAUVIGNON BLANC, Serge Laloue, “Cuvee Silex,” Sancerre, France, 2013 ........................... 13.75 REDS BAROLO, G.D. Vajra, “Albe,” Piedmont, Italy, 2010 ................................................................ 17.85 BORDEAUX, Château Phélan Ségur, Saint-Estèphe, France, 2010 ....................................... 26.75 BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO, Caparzo, Italy, 2009 .................................................................. 18.95 CABERNET FRANC, Olga Raffault, “Les Picasses,” Chinon, France, 2010 .......................... 13 A beautiful cabernet franc from perhaps the greatest region—certainly the most undervalued—for the grape in the world, Chinon. -

Zinfandel Tips

Tips for Making Great Z I N F A N D E L Zinfandel is a lush, fruity grape that is adaptable to many terriors, but is best in warm (but not too hot) climates with cool nights. Picked early, it has more acid and strawberry flavors; picked late and it can have a jammy, blackberry flavor and can sustain alcohol approaching 16 percent. DNA typing has shown that the Italian grape, Primitivo, and Zinfandel are clones of the same grape. Primitivo is a superior grape, from a grower’s standpoint, to Zinfandel. It also is made in a darker, spicier style than most American Zinfandels. The EU recognized Zinfandel and Primitivo as synonymous in 1999. In 2007, the U.S. TTB listed both wines as approved grape varietals – but they are NOT synonymous. Zins must be labeled as Zins, and Primitivos must be labeled as Primitivos 1. Of course, start with good fruit. We believe the Club Project fruit will be top notch Zinfandel from one of the best Zinfandel terriors in the world, the Sierra Foothills. 2. Harvest brix should be between 24 and 25.5 degrees (see note 1). When you get this must home, immediately check the pH and the TA. The pH is likely to be a little high (3.60+) and acid low (perhaps .50 g/l or so). My advice is to carefully add tartaric acid in stages to bring the pH down to about 3.35 to 3.40 3. Consider adding pectic enzyme before fermentation to aid in color extraction (2.5 to 5.0 grams per 100 liters). -

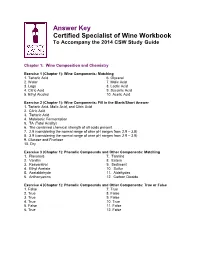

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Olivier Horiot Profile

Olivier Horiot Profile In the southern-most part of the Champagne region, the Côte des Bar in the Aube department, there is the town of Les Riceys, where the slopes are blessed with the portlandian formation of Kimmeridgian chalk, that same great stuff that is the foundation of the finest Chablis and Sancerre. Except here the idea was to plant Pinot Noir on these chalky slopes, do a long maceration, often using whole bunches, and then age it a few years (at least 3) before release -- not exactly your average deck wine. Olivier Horiot took over the estate of his father Serge in 1999; though it bears his name due to inheritance, his wife Marie is essential to day to day operations and runs the cellar. They immediately started using organic and some biodynamic practices, as well as highlighting specific parcels in the effort of being more terroir-focused. In order to make the Rosé des Riceys, the Horiot do a very strict selection of grapes from two separate sites - en Valingrain and en Barmont - vinifying them separately. The wines start with about 10% of the grapes foot-trodden at the bottom of the cuve, then whole bunches are added. Macerations usually last 5-6 days, with pumping over twice a day. After the wine is racked into older barrels, it remains there for a few years before being bottled without fining or filtration. The Horiot also produce 4 Champagnes: a Blanc de Noir from the en Barmont site named Sève, two blends of multiple parcels, 5 Sens and Métisse, as well as a quirky, unexpected Champagne produced with the Arbane grape, aptly named Arbane. -

The Judges' Newsletter

THE JUDGES' NEWSLETTER NATIONAL GUILD OF WINE AND BEER JUDGES Confidential to Members No. 3 1990 Rcycroft, De v o n sends his cvr. views cr. the attributes cf — at.c Gooseberry ir. respcr.se to ar. article which appeared first 1990 issue of this Guild Newsletter - read on. Ed. * > GOOSEBERRY FOOL I was intrigued by the list of aromas (not bouq-uets!) and/or flavours attributed to gooseberry wines - foot of page 18 JNL1/9G AMYL ACETATE and AMYL ACETONE - and PEARDROPS were probably mistaken fcr ETHYL ACETATE as they have some affinity, though they are distinct to anyone who really knows them. ETHYL ACETATE is an essential part of the 'fruity' nose of wine but in some youngish gooseberry wine the ethyl acetate can be individually stronger than normal. The wines are better aged. Ignoring ar overdose, noticeable, sulphite in a finished wine could be the result of high acidity. NAPTHALENE, SCOT £ SMOKE I have never encountered in my 3 5years of making gooseberry wines!. However, during my early years of winemaking I did get a flavour that was not mentioned in the JNL article. This was a flavour, confirmed by other Judges and which I called "Gooseberry Mouse", after my experience of the common 'bacterial mouse' of poor wines NOI, GOOSEBERRY MOUSE is definitely NOT "Bacterial Mouse" - to which I am allergic. Gooseberry Mouse is-softer, not pervading and does r.ot stay or. the palate as an aftertaste though there is, in my opinion, some similarity in the first taste. Evidence against it being "Bacterial Mouse" is that long before I made wine I had noticed this flavour in cooked gooseberry pies etc. -

Wine Labels and Consumer Culture in the United States

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 7.1. | 2018 Visualizing Consumer Culture Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States Eléonore Obis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1029 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference Eléonore Obis, « Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States », InMedia [Online], 7.1. | 2018, Online since 20 December 2018, connection on 08 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1029 This text was automatically generated on 8 September 2020. © InMedia Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States 1 Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States Eléonore Obis Introduction Preliminary remarks 1 The wine market is a rich object of study when dealing with the commodification of visual culture. Today, it has to deal with a number of issues to promote wine, especially market segmentation, health regulations and brand image. First, it is important to find the right market segment as wine can be a luxury, collectible product that people want to invest in.1 At the other end of the spectrum, it can be affordable and designed for everyday consumption (table wine). The current trend is towards democratization and convergence in the New World, as wine and spirits consumption is increasing in countries that traditionally drink beer.2 Second, the market has to reconcile pleasure with health legislations imposed by governments and respect the health regulations of the country. The wine label is the epitome of this tension between what regulations impose and what the winemaker intends to say about the wine in order to sell it.