Transplanted Or Uprooted?: Integration Efforts of Bosnian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sportjahresbericht 2011

SPORTJAHRESBERICHT 2011 SPORTJAHRESBERICHT 2011 INHALT Badminton 3 Basketball 8 Fechten 11 Handball 12 Inline Hockey 18 Integration und Behindertensport 18 Judo 20 Kanu 21 Kegeln 23 Kunstturnen 24 Leichtathletik 26 Orientierungslauf 28 Rhythmische Gymnsatik 32 SPOKI 34 Tanzen 36 Tennis 38 Tischtennis 51 Trampolinspringen 53 Volleyball 56 2 SPORTJAHRESBERICHT 2011 BADMINTON WBH Wien 3. Weißenbäck / Vattanirappel im HD 2. Vattanirappel V. / Mathis im MXD Österreichische Meisterschaften der Junioren (U22) 2011 3. Vattanirappel V. im HE Österreichische Meisterschaften der Jugend (U17/ U19) 2011 1. Vattanirappel V. im HE (U19) 2. Vattanirappel V. / Trojan D. im HD (U19) 1. Vattanirappel V. / Mathis A im MXD (U19) Österreichische Meisterschaften der Schüler (U13 / U15) 2011 2. Opelc P. / Birker P im HD (U13) 2. Fink F. / Seiwald L. im HD (U15) ASKÖ Bundesmeisterschaften 2010/2011 1. Philipp Opelc/Gabriel Semerl (U13-Burschendoppel) 1. Armin Griebler/Christoph Syrch (U15-Burschendoppel) 1. Tina Riedl/Anna Demmelmayer (Damendoppel – Allgemeine Klasse) 2.Philipp Opelc/Conny Ertl (U13-Mixeddoppel) 2. Vilson Vattanirappel/Julia Frantes (Mixed Doppel – Allgemeine Klasse) 3.Philipp Opelc (U13-Burscheneinzel) 3. Felix Fink (U15-Burscheneinzel) 3. Armin Griebler (U15-Burscheneinzel) 3.Felix Fink/Hubert Nahrebecki (U15-Burschendoppel) 3.Hubert Nahrebecki/Manuela Kral (U15-Mixeddoppel) 3.Lukas Weißenbäck (Herreneinzel – Allgemeine Klasse) 3. Vilson Vattanirappel/Lukas Weißenbäck (Herrendoppel – Allgemeine Klasse) 1. A-RLT 2010/2011 3. Lukas Weißenbäck / Vilson Vattanirappel im HD 2. Vilson Vattanirappel / Mathis Alexandra im MXD 2. A-RLT 2010/2011 3. Georg Cejnek / Jun Mai im HD 2. Vilson Vattanirappel / Mathis Alexandra im MXD 3. A-RLT 2010/2011 1. Vattanirappel V. / Weißenbäck L. -

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ivana Bago 2018 Abstract The dissertation examines the work contemporary artists, curators, and scholars who have, in the last two decades, addressed urgent political and economic questions by revisiting the legacies of the Yugoslav twentieth century: multinationalism, socialist self-management, non- alignment, and -

When Cultures Collide: LEADING ACROSS CULTURES

When Cultures Collide: LEADING ACROSS CULTURES Richard D. Lewis Nicholas Brealey International 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page i # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page ii page # blind folio 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page iii ✦ When Cultures Collide ✦ LEADING ACROSS CULTURES # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page iv page # blind folio 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page v ✦ When Cultures Collide ✦ LEADING ACROSS CULTURES A Major New Edition of the Global Guide Richard D. Lewis # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page vi First published in hardback by Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 1996. This revised edition first published in 2006. 100 City Hall Plaza, Suite 501 3-5 Spafield Street, Clerkenwell Boston, MA 02108, USA London, EC1R 4QB, UK Information: 617-523-3801 Tel: +44-(0)-207-239-0360 Fax: 617-523-3708 Fax: +44-(0)-207-239-0370 www.nicholasbrealey.com www.nbrealey-books.com © 2006, 1999, 1996 by Richard D. Lewis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Printed in Finland by WS Bookwell. 10 09 08 07 06 12345 ISBN-13: 978-1-904838-02-9 ISBN-10: 1-904838-02-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, Richard D. -

VOLUNTARY NATIONAL REVIEW North Macedonia July 2020

VOLUNTARY NATIONAL REVIEW North Macedonia July 2020 North Macedonia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Coordination of the process of the National Voluntary Review and contribution to the Review was provided by Ana Jovanovska - Head of unit for Sustainable Development Unit from the Cabinet of Deputy President of the Government in Charge for Economic Affairs and Coordination of Economic Departments. Coordination of data collection and contribution to the Statistical Annex was provided by Snezana Sipovikj - Head of Unit for structural business statistics, business demography and FATS statistics, from the State Statistical Office. Acknowledgments for the contribution to the review: Office of the Prime minister Refet Hajdari The National Academy of Dushko Uzunoski Elena Ivanovska Science and arts Lura Pollozhani Ministry of Economy Chamber of commerce of Ivanna Hadjievska Macedonia Dane Taleski Marina Arsova Ilija Zupanovski Biljana Stojanovska Union of Chambers of Jasmina Majstorovska Commerce Cabinet of the Deputy Bekim Hadziu President in charge for Sofket Hazari MASIT economic affairs Blerim Zlarku Eva Bakalova Ministry of Health The process was supported by: Elena Trpeska Sandra Andovska Biljana Celevska Ksenija Nikolova Elena Kosevska Daniel Josifovski Mihajlo Kostovski Dane Josifovski Ministy of Education Viktor Andonov Filip Iliev Nadica Kostoska Bojan Atanasovski Ministry of Transport and General Secretariat of the Connections Government – Unit for Jasminka Kirkova collaboration with the Civil Society Organizations Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry -

LCC-Wien Silvesterlauf 2012 Ergebnisliste Silvesterlauf - 5.325M - Nach Zeit Sortiert 2012-12-31 Seite 1

LCC-Wien Silvesterlauf 2012 Ergebnisliste Silvesterlauf - 5.325m - nach Zeit sortiert 2012-12-31 Seite 1 Rang Stnr Name Jg. Nat. Verein/Ort Altersklasse KRg. Brutto/Rg. Netto 1 2 Pratscher Dieter 80 AUT RCLA Bad Tatzmannsdorf M-30 1 0:16:22/1. 0:16:22 2 3361 Listabarth Stephan 93 AUT DSG Volksbank Wien M-U20 1 0:16:39/2. 0:16:39 3 3908 Heigl Thomas 80 AUT LCCWien M-30 2 0:16:49/3. 0:16:49 4 1793 Asamer Raphael 92 AUT ULC Riverside Mödling M-20 1 0:16:55/4. 0:16:55 5 708 Thanner Wilfried, Dr. 81 AUT Wien M-30 3 0:17:08/5. 0:17:08 6 2395 Gremmel Helmut 90 AUT HSV Pinkafeld M-20 2 0:17:10/6. 0:17:10 7 2249 Stieglechner Andreas 84 AUT LC Waldviertel M-20 3 0:17:19/7. 0:17:18 8 1987 Singer Michael 95 AUT LaufSportPraxis M-U20 2 0:17:26/8. 0:17:26 9 3542 Krenn Alexander 75 AUT Castrol Edge Powerteam M-30 4 0:17:29/9. 0:17:28 10 265 Baumgarth Achim 77 GER Phönix Lübeck M-30 5 0:17:34/10. 0:17:33 11 2650 Klemen Bernhard 84 AUT USC Theresianum M-20 4 0:17:43/11. 0:17:41 12 3180 Helleport Harald 71 AUT run42195.at M-40 1 0:18:03/12. 0:18:01 13 2300 Scharmer Josef 62 AUT Lg Telfs M-50 1 0:18:10/13. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 35663 Mr

November 1, 1973 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 35663 Mr. EDWARDS of California., Mr. FREN require arbitration of certain amateur PETTIS, Mr. DUNCAN, Mr. BROTZMAN, ZEL, Mr. HORTON, Mr. KEATING, Mr. athletic disputes, and for other purposes; to and Mr, ARcHER) : KEMP, Mr. KETCHUM, Mr. LEGGETT, the Committee on the Judiciary. H.R. 11251. A bill to amend the Tariff Mr. MITCHELL of Maryland, Mr. By Mr. MOAKLEY (for himself, Mr. Schedules of the United States to provide for MOAKLEY, Mr. MOLLOHAN, Mr. NIX, ROSENTHAL, and Mr. CHARLES H. the duty-free entry of methanol imported Mr. O'HARA, Mr. RANGEL, Mr. RoE, WILSoN of California) : for use as fuel; to the Committee on Ways Mrs. SCHROEDER, Mr. THOMPSON of H.R. 11243. A bill to amend title 3 of the and Means. New Jersey, Mr. UDALL, Mr. WIDNALL, United States Code to provide for the order By Mr. WALDIE: Mr. YATES, and Mr. YATRON): of succession in the case of a. vacancy both H.R. 11252. A bill to amend title 5, United H.R. 11233. A bill to provide for the con in the Office of President and Office of the States Code, to provide for the reclassifica servation of energy through observance of Vice President, to provide for a special elec tion of certain security police positions of daylight saving time on a. year-round basis; tion procedure in the case of such vacancy, the Department of the Navy a.t China Lake, to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign and for other purposes; to the Committee Calif., and for other purposes; to the Com Commerce. -

The Beer Guide to Prague Over 60 of the Best Beer Experiences in and Around Prague

The Beer Guide to Prague Over 60 of the Best Beer Experiences in and around Prague BeerinPrague.com Contents Prague – The Best Beer City in Europe . 4 Classic Czech Pub Etiquette . 6 Glossary of Beer Styles and Terms . 8 The Beer Guide to Prague Breweries & Brewpubs Klášterní pivovar Strahov . 11 U Medvídků Restaurant and Brewery . 12 U Dobřenských Brewery . 13 U Fleků Brewery and Restaurant . 13 U tří růží Brewery and Restaurant . 15 U Supa Brewery and Restaurant . 16 Novoměstský pivovar . 16 Národní Brewery . 17 Nota Bene and Beerpoint . 19 Pivovarský dům . 20 Vinohradský pivovar . 20 Loď Pivovar . 21 Sousedský pivovar Bašta and U Bansethů Restaurant . 22 Sv . Vojtěch Břevnov Monastic Brewery . 23 U Bulovky Brewery . 24 Únětice Brewery and Restaurant . 24 Beer Bars & Multi-Tap Pubs Pípa – Beer Story Dlouhá . 26 U Kunštátů – Craft Beer Club . .. 26 Craft House . 27 Gulden Draak Bierhuis . 28 20 PIP Craft Beer Pub . 29 BeerGeek Bar . 30 Dno pytle . 30 Prague Beer Museum . 31 Bad Flash Bar . 32 InCider Bar . 32 Pivovarský klub . 33 Good Food, Good Beer Kolkovna Olympia Restaurant . 34 Lokál Dlouhááá . 35 T-Anker Restaurant . 36 The James Joyce Irish Pub . 37 Maso a kobliha . .. 38 Kulový Blesk Restaurant . 39 Bruxx Belgian Restaurant . 40 DISH . 41 Los v Oslu . 41 The Tavern . 42 U Bulínů Restaurant . 43 Vinohradský Parlament Restaurant . 43 U Kurelů Restaurant . 44 Zlý Časy Beerhall and Beer-Shop . 44 Podolka Restaurant . 45 Beer & Atmosphere (Classic Prague Pubs & Beer Gardens) U Černého Vola . .. 46 U Hrocha Beerhall . 46 U Zlatého tygra Beerhall . 47 U Pinkasů Restaurant . .. 48 Park Café Restaurant . -

Preventing and Combating Human Trafficking in North Macedonia

Preventing and Combating Human Trafficking in North Macedonia What is the goal? ► To support the implementation of the recommendations resulting from the monitoring of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by North Macedonia, in particular with a view to improving the identification, protection of and assistance to victims of human trafficking in line with the European standards. Who benefits from the project? ► End beneficiaries: victims and persons at risk of trafficking in human beings ► Key beneficiary institutions, including National Commission for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Illegal Migration, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy and State Labour Inspectorate, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health as well as civil society organisations and selected private sector actors. How will the project work? ► Legislative, policy and research support ► Multi-disciplinary trainings ► Seminars ► Awareness raising events What do we expect to achieve? ► Improved detection and identification of, and assistance to victims of human trafficking for the purpose of labour exploitation ► Labour inspectors and other key anti-trafficking stakeholders are involved in the identification of victims of trafficking and their referral to assistance and protection ► Enhanced detection and identification of, and assistance to child victims of human trafficking ► Improved access to compensation for victims of human trafficking ► Greater awareness of all actors, and of general public, about specific vulnerabilities to trafficking situations and the rights of trafficked persons How much will it cost? ► The total budget of the Action is 715.000 Euros ► The budget allocated to the overall Horizontal Facility programme amounts to ca. -

What's the Score? a Survey of Cultural Diversity and Racism in Australian

What’s the score? A survey of cultural diversity and racism in Australian sport © Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 2006. ISBN 0 642 27001 5 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Requests and enquiries concerning the reproduction of materials should be directed to the: Public Affairs Unit Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission GPO Box 5218 Sydney NSW 2001 [email protected] www.humanrights.gov.au Report to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. The report was written and produced by Paul Oliver (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission). Cover photograph: Aboriginal Football, © Sean Garnsworthy/ALLSPORT. Aboriginal boys play a game of Australian Rules football along the beach in Weipa, North Queensland, June 2000. Contents Foreword 5 Introduction 7 Project Overview and Methodology 1 Executive Summary 19 National Sporting Organisations Australian rules football: Australian Football League 2 Athletics: Athletics Australia 41 Basketball: Basketball Australia 49 Boxing: Boxing Australia Inc. 61 Cricket: Cricket Australia 69 Cycling: Cycling Australia 8 Football (Soccer): Football Federation Australia 91 Hockey: Hockey Australia 107 Netball: Netball Australia 117 Rugby league: National Rugby League and Australian Rugby League 127 Rugby union: Australian Rugby Union 145 Softball: Softball Australia 159 Surf lifesaving: Surf Life Saving Australia -

Unofficial Storytelling As Middle Ground Between Transitional Truth-Telling and Forgetting: a New Approach to Dealing with the Past in Postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina

DOI: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.638 IJCV: Vol. 13/2019 Unofficial Storytelling as Middle Ground Between Transitional Truth-Telling and Forgetting: A New Approach to Dealing With the Past in Postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina Hana Oberpfalzerová Institute of Political Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague [email protected] Johannes Ullrich Department of Psychology, University of Zurich [email protected] Hynek Jeřábek Institute of Sociological Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague Vol. 13/2019 The IJCV provides a forum for scientific exchange and public dissemination of up-to-date scien- tific knowledge on conflict and violence. The IJCV is independent, peer reviewed, open access, and included in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) as well as other rele- vant databases (e.g., SCOPUS, EBSCO, ProQuest, DNB). The topics on which we concentrate—conflict and violence—have always been central to various disciplines. Consequently, the journal encompasses contributions from a wide range of disciplines, including criminology, economics, education, ethnology, his- tory, political science, psychology, social anthropology, sociology, the study of reli- gions, and urban studies. All articles are gathered in yearly volumes, identified by a DOI with article-wise pagi- nation. For more information please visit www.ijcv.org Suggested Citation: APA: Oberpfalzerová, H., Ullrich, J., Jeřábek, H. (2019). Unofficial Storytelling as Middle Ground Between Transi-tional Truth-Telling and Forgetting: A New Approach to Deal- ing With the Past in Postwar Bosnia and Herze-govina, 2019. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 13, 1-19. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.638 Harvard: Oberpfalzerová, Hana, Ullrich, Johannes, Jeřábek, Hynek. -

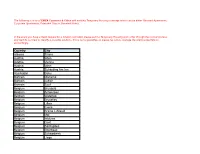

EMEA Countries & Cities with Existing Temporary Housing Coverage Which Can Be Either Serviced Apartments, Corporate Apartments, Extended Stay Or Standard Hotels

The following is a list of EMEA Countries & Cities with existing Temporary Housing coverage which can be either Serviced Apartments, Corporate Apartments, Extended Stay or Standard Hotels. In the event you have a client request for a location not listed, please send a Temporary Housing work order through the normal process and we'll do our best to identify a possible solution - this is not a guarantee so please be sure to manage the clients expectations acccordingly. Country City Albania Tirana Austria Wien Austria Vienna Austria Wein Austria Schärding Am Inn Azerbaijan Baku Bahrain Manama Bahrain Juffair Bahrain Seef Belgium Brussels Belgium Antwerpen Belgium Waterloo Belgium Bruxelles Belgium Lillois Belgium Evere Belgium Braine L'Alleud Belgium Mol Belgium Woluwe Belgium Gent Belgium Saint-gilles Belgium Etterbeek Belgium Schaarbeek Belgium Liege Belgium Ghent Belgium Geel Belgium Turnhout Belgium Tassenderlo Belgium Mons Belgium Epinal Belgium Leuven Belgium Belgique Belgium Ixelles Bulgaria Sofia Croatia Zagreb Cyprus Nicosia Czech Republic Prague Czech Republic Pekarska Czech Republic Brno Czech Republic Praha Denmark Copenhagen Denmark Kobenhavn Denmark Aarhus Denmark Charlottenlund Denmark Mejlgade Denmark Middelfart Denmark Hellerup Egypt Cairo Estonia Tallinn Estonia Tallin Finland Helsinki Finland Espoo Finland Tampere Finland Turku France Paris France Courbevoie France Grenoble France Neuilly-sur-seine France Lyon France Issy-les-Moulineaux France Courbefvoie France Toulouse France Lille France Nice France La Defense France -

IRGC Stages Massive Military Exercise

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 12 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13723 Wednesday JULY 29, 2020 Mordad 8, 1399 Dhul Hijjah 8, 1441 11 individuals convicted Six U.S. mayors urge Hadi Saei chosen as Venice Film Festival for disrupting Iran’s Congress to block Trump head of Iran’s Athletes’ picks three movies currency market 3 federal deployment 10 Commission 11 from Iran 12 Iran’s foreign debt falls 4.1%: CBI TEHRAN – The latest report published External debt is the portion of a coun- IRGC stages massive by the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) puts the try’s debt that is borrowed from foreign country’s foreign debt at $8.655 billion at lenders including commercial banks, the end of the first quarter of the current governments or international financial Iranian calendar year (June 20), down institutions. These loans, including inter- 4.16 percent from $9.031 billion at the est, must usually be paid in the currency See page 3 end of the previous year, IRNA reported. in which the loan was made. From the total foreign debt, $7.163 Foreign debt as a percentage of Gross billion was mid-term and long-term debts Domestic Product (GDP) is the ratio be- military exercise while $1.492 billion was short-term debts, tween the debt a country owes to non-res- the report confirmed ident creditors and its nominal GDP. Post-coronavirus world order ‘not entirely Western’, Zarif predicts TEHRAN – Iranian Foreign Minister sation with English-speaking audience Mohammad Javad Zarif has predicted from Tehran on Monday, Zarif said the that the post-coronavirus world order past 30 years have constituted one of the would not be totally Western anymore, most turbulent junctures in the world’s saying that Western countries have failed history, which has been marked with var- to develop a proper understanding of the ious wars as well as cataclysmic changes realities on the ground.