Migration in Austria Günter Bischof, Dirk Rupnow (Eds.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Elections in Austria -‐ Social Democrats Remain Stable, Gains for P

Parliamentary elections in Austria - Social Democrats remain stable, gains for right-wing parties By Maria Maltschnig, director of the Karl-Renner-Institute1 October 2017 The SPÖ has retained its 52 mandates, but has had to hand over first place to the conservative ÖVP, which gained 7.5 percentage points. The SPÖ gained more than 100,000 votes in total. The SPÖ was able to win votes mostly from non-voters and former green voters, but mostly lost votes to the right-wing populist FPÖ. Overall, we see a shift of about 4% points from the left-wing parties to the right. The liberal NEOS, which cannot be attributed to either of the two camps, remained stable, while the Greens suffered heavy losses and remained below the 4% hurdle to enter the National Parliament. Even if this is hardly a landslide victory for the right-wing parties, there is still a clear shift to the right. In addition to the percentage movement in favour of the right-wing parties, a clear rhetorical and substantive reorientation of the ÖVP from being a classical conservative party to being a party with right-wing populist tendencies can also be observed. The programmes of the ÖVP and FPÖ extensively overlap. There are three major reasons for this result: 1) Since the summer of 2015, when hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants travelled through Austria - many of whom have stayed - the issues of asylum, migration and integration have dominated the debate and are strongly associated with issues of internal security and crime. Many Austrians perceived the events of 2015 and thereafter as a severe loss of control by the state and politicians. -

Schulen in Vorarlberg 9

Schulen in Vorarlberg 9. 1 10. 11. 12. 13. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Polytechnische Bludenz, Bartholomäberg-Gantschier, Thüringen, Bregenz, Hittisau, Sozialberufe Bildungsanstalt für Elementarpädagogik (BAfEP) Schulen Bezau, Kleinwalsertal, Dornbirn, Feldkirch, Rankweil, Lauterach Feldkirch Voraussetzung: Kolleg für Elementarpädagogik BB BB BB AHS – Oberstufen Gymnasium Feldkirch Matura, BRP, SBP Bludenz, Bregenz (4x), Dornbirn (2x), Feldkirch, Lustenau Langformen Voraussetzung : Kolleg Dual für Elementarpädagogik Matura, BRP, SBP, BB BB BB BB Berufserfahrung Realgymnasium Feldkirch Bludenz, Bregenz, Dornbirn (2x), Feldkirch (2x) Fachschule für Pflege und Gesundheit Feldkirch AHS – Oberstufen ORG Schwerpunkt: Instrumentalunterricht Oberstufen- Dornbirn, Egg, Feldkirch, Götzis, Lauterach Technische Fachschule Maschinenbau - Fertigungstechnik + realgymnasium Schulen Werkzeug- und Vorrichtungsbau (ORG) ORG Schwerpunkt: Bildn. Gestalten + Werkerziehung HTL Maschinenbau Dornbirn, Egg, Feldkirch, Götzis, Lauterach HTL Bregenz HTL Automatisierungstechnik Smart Factory ORG Schwerpunkt: Naturwissenschaft Egg, Feldkirch, Götzis, Lauterach HTL Kunststofftechnik Product + Process Engineering ORG Bewegung & Gesundheit Bludenz HTL Elektrotechnik Smart Power + Motion ORG Wirtschaft & Digitales Voraus s etzung: Matura, B R P, SBP od. einschl. Fachschule od. Bludenz Kolleg/Aufbaulehrgang Maschinenbau Lehre u. Vorbereitungslg. oder Sportgymnasium, Dornbirn Technische Fachschule für Chemie Schulen Musikgymnasium, Feldkirch HTL Dornbirn Fachschule für Informationstechnik -

Danube River Cruise Flyer-KCTS9-MAURO V2.Indd

AlkiAlki ToursTours DanubeDanube RiverRiver CruiseCruise Join and Mauro & SAVE $800 Connie Golmarvi from Assaggio per couple Ristorante on an Exclusive Cruise aboard the Amadeus Queen October 15-26, 2018 3 Nights Prague & 7 Nights River Cruise from Passau to Budapest • Vienna • Linz • Melk • and More! PRAGUE CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA GERMANY Cruise Route Emmersdorf Passau Bratislava Motorcoach Route Linz Vienna Budapest Extension MUNICH Melk AUSTRIA HUNGARY 206.935.6848 • www.alkitours.com 6417-A Fauntleroy Way SW • Seattle, WA 98136 TOUR DATES: October *15-26, 2018 12 Days LAND ONLY PRICE: As low as $4249 per person/do if you book early! Sail right into the pages of a storybook along the legendary Danube, *Tour dates include a travel day to Prague. Call for special, through pages gilded with history, and past the turrets and towers of castles optional Oct 15th airfare pricing. steeped in legend. You’ll meander along the fabled “Blue Danube” to grand cities like Vienna and Budapest where kings and queens once waltzed, and to gingerbread towns that evoke tales of Hansel and Gretel and the Brothers Grimm. If you listen closely, you might hear the haunting melody of the Lorelei siren herself as you cruise past her infamous river cliff post! PEAK SEASON, Five-Star Escorted During this 12-day journey, encounter the grand cities and quaint villages along European Cruise & Tour the celebrated Danube River. Explore both sides of Hungary’s capital–traditional Vacation Includes: “Buda” and the more cosmopolitan “Pest”–and from Fishermen’s Bastion, see how the river divides this fascinating city. Experience Vienna’s imperial architec- • Welcome dinner ture and gracious culture, and tour riverside towns in Austria’s Wachau Valley. -

20131111 Medienunternehmen

Österreichs größte Medienunternehmen der Standard hat die aktuellsten Umsätze, Mitarbeiterzahlen und Ergebnis- Auf die Quelle weisen die Dreiecke hin. Die Rubrik Medien nennt wesentliche, se der Sender, Verlage und Agenturen zusammengetragen. Die meisten Daten aber nicht alle Titel, Verlage, Sender, Plattformen mit Reichweiten und Marktan- nannten die Player selbst – für das Jahr 2012. Wo sie schwiegen, liefern das Fir- teilen. Neue Daten, Änderungen und allfällige Korrekturen finden Sie dann in menbuch (meist nicht so aktuelle) Werte oder Schätzungen Größenordnungen. aktualisierten Übersichten auf derStandard.at/Etat Gebühren: 595,5 Mio. Euro KENNZAHLEN u Umsatz 2011/12: 452,8 Millionen Euro (2010/11: 466,3 Mio.) (584,2 Mio.) Mediaprint u Konzernergebnis (EGT) 2011/2012: 4,6 Millionen Euro (2010/11: 20,1 Mio.) u Mitarbeiter: 1161 (2010/11: 1166) Umsatz: Werbung: 262 Mio. Euro EIGENTÜMER Kronen Zeitung (50 %), Kurier (50 %) (264,0 Mio.) Kommanditanteile/Gewinnaufteilung: Krone 70 %, Kurier 30 % ORF Krone gehört: Hans Dichand 2010 (50 %, Erbe laut Firmenbuch noch nicht geregelt), WAZ (50 %) TV/Radio: 452,8 † Kurier gehört: Raiffeisen (rund 50,56 %), WAZ (49,44 %) 210,7 Mio. Euro (216,7 Mio.) Millionen Euro Online: MEDIEN Tageszeitungen: zKronen Zeitung dominiert mit 37,4 % Reichweite (38,2) den Zeitungsmarkt Umsatz: 9,7 Mio. Euro (9,0 Mio.) zKurier: 8,5 % (8,1), Mediaprint ist gemeinsamer Verlag | Magazine: Zeitungsbeilagen wie zkrone.tv zkurier.tv zfreizeit z Kurier hält 25,3 % an Verlagsgruppe News (unten) | Radio: zKronehit (einziges -

On Burgenland Croatian Isoglosses Peter

Dutch Contributions to the Fourteenth International Congress of Slavists, Ohrid: Linguistics (SSGL 34), Amsterdam – New York, Rodopi, 293-331. ON BURGENLAND CROATIAN ISOGLOSSES PETER HOUTZAGERS 1. Introduction Among the Croatian dialects spoken in the Austrian province of Burgenland and the adjoining areas1 all three main dialect groups of central South Slavic2 are represented. However, the dialects have a considerable number of characteris- tics in common.3 The usual explanation for this is (1) the fact that they have been neighbours from the 16th century, when the Ot- toman invasions caused mass migrations from Croatia, Slavonia and Bos- nia; (2) the assumption that at least most of them were already neighbours before that. Ad (1) Map 14 shows the present-day and past situation in the Burgenland. The different varieties of Burgenland Croatian (henceforth “BC groups”) that are spoken nowadays and from which linguistic material is available each have their own icon. 5 1 For the sake of brevity the term “Burgenland” in this paper will include the adjoining areas inside and outside Austria where speakers of Croatian dialects can or could be found: the prov- ince of Niederösterreich, the region around Bratislava in Slovakia, a small area in the south of Moravia (Czech Republic), the Hungarian side of the Austrian-Hungarian border and an area somewhat deeper into Hungary east of Sopron and between Bratislava and Gyǡr. As can be seen from Map 1, many locations are very far from the Burgenland in the administrative sense. 2 With this term I refer to the dialect continuum formerly known as “Serbo-Croatian”. -

Racism and Cultural Diversity in the Mass Media

RACISM AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN THE MASS MEDIA An overview of research and examples of good practice in the EU Member States, 1995-2000 on behalf of the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia, Vienna (EUMC) by European Research Centre on Migration and Ethnic Relations (ERCOMER) Edited by Jessika ter Wal Vienna, February 2002 DISCLAIMER ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ This Report has been carried out by the European Research Centre on Migration and Ethnic Relations (ERCOMER) on behalf of the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC). The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the position of the EUMC. Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged and the attached text accompanies any reproduction: "This study has been carried out on behalf of the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC). The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the position of the EUMC." 2 PREFACE The research interest in analysing the way mass media report on ethnic issues has increased in the Member States over the last decades. And for this reason the EUMC decided to bring together the major research reports and their findings over the last five years in this report "RACISM AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN THE MASS MEDIA - an overview of research and examples of good practice in the EU Member States, 1995- 2000". The project has been carried out by Dr Jessika ter Wal, at Ercomer, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to her for her excellent work. The report underlines the importance of media research in the area of racism and diversity. -

Prairie Sentinelvolume 8

Illinois National Guard Prairie SentinelVolume 8 On the Road Again: 233rd Military Police Company Conducts Road to War Training Homeward Bound: 2nd Battalion, 13oth Infantry Regiment Returns home Best of the BEST: Bilateral Embedded Staff Team A-25 caps off BEST co-deployment missions Nov-Dec 2020 Illinois National Guard 6 8 9 10 12 15 16 18 21 22 24 For more, click a photo or the title of the story. Highlighting Diversity: ILNG Diversity Council host Native American speaker 4 The Illinois National Guard Diversity Council hosts CMSgt, Teresa Ray. By Sgt. LeAnne Withrow, 139th MPAD ILARNG Top Recruiter and first sergeant from same company 5 Company D, Illinois Army National Guard Recruiting and Retention Battalion based in Aurora, Illinois, is the home of the top recruiter and recruiting first sergeant. By Sgt. 1st Class Kassidy Snyder, Illinois Army National Guard Recruiting and Retention Battalion Homeward Bound: 2/130’s Companies B and C return home 6 Soldiers from 2nd Battalion, 130th Infantry Regiment’s B and C companies return home after deploying to Bahrain and Jordan Oct. 31. By Barb Wilson, Illinois National Guard Public Affairs Joint Force Medical Detachment commander promoted to colonel 8 Jayson Coble, of Lincoln, Illinois, was promoted to the rank of colonel Nov. 7 at the Illinois State Military Museum. By Barb Wilson, Illinois National Guard Public Affairs High Capacity: 126th Maintenance Group Earns fourth consecutive mission capability title 9 A photo spread highlighting the 126th MXG’s quintuple success. By Tech. Sgt. Cesaron White and Senior Airman Elise Stout, 126th Air Refueling Wing Public Affairs Back to back, Shoulder to Shoulder: 108th earns back to back sustainment awards 10 Two exceptional Illinois Army National Guard teams won the prestigious U.S. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

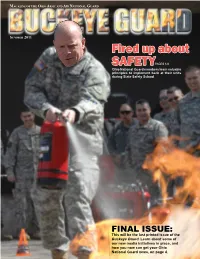

Summer 2011 Fired up About

MAGAZINE OF THE OHIO ARMY AND AIR NATIONAL GUARD SUMMER 2011 Fired up about SAFETYPAGES 8-9 Ohio National Guard members learn valuable principles to implement back at their units during State Safety School FINAL ISSUE: This will be the last printed issue of the Buckeye Guard. Learn about some of our new media initiatives in place, and how you now can get your Ohio National Guard news, on page 4. GUARD SNAPSHOTS BUCKEYE GUARD roll call Volume 34, No. 2 Summer 2011 The Buckeye Guard is an authorized publication for members Sgt. Corey Giere of the Department of Defense. Contents of the Buckeye Guard (right) of Headquarters are not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, the Departments of the Army and Air Force, or and Headquarters the Adjutant General of Ohio. The Buckeye Guard is published Company, Special quarterly under the supervision of the Public Affairs Office, Ohio Adjutant General’s Department, 2825 W. Dublin Granville Troops Battalion, Road, Columbus, Ohio 43235-2789. The editorial content of this 37th Infantry Brigade publication is the responsibility of the Adjutant General of Ohio’s Director of Communications. Direct communication is authorized Combat Team, to the editor, phone: (614) 336-7003; fax: (614) 336-7410; or provides suppressive send e-mail to [email protected]. The Buckeye Guard is distributed free to members of the Ohio Army and Air fire with blank rounds National Guard and to other interested persons at their request. as the rest of his fire Guard members and their Families are encouraged to submit any articles meant to inform, educate or entertain Buckeye Guard team runs for cover readers, including stories about interesting Guard personalities and unique unit training. -

Centrope Location Marketing Brochure

Invest in opportunities. Invest in centrope. Central European Region Located at the heart of the European Union, centrope is a booming intersection of four countries, crossing the borders of Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. The unique mixture of sustained economic growth and high quality of life in this area offers tremendous opportunities for investors looking for solid business. A stable, predictable political and economic situation. Attractive corporate tax rates. A highly qualified workforce at reasonable labour costs. World-class infrastruc- ture. A rich cultural life based on shared history. Beautiful landscapes including several national parks. And much more. The centrope region meets all expectations. meet opportunities. meet centrope. Vibrant Region Roughly six and a half million people live in the Central European Region centrope. The position of this region at the intersection of four countries and four languages is reflected in the great variety of its constituent sub-regions and cities. The two capitals Bratislava and Vienna, whose agglomerations – the “twin cities” – are situated at only 60 kilometres from each other, Brno and Győr as additional cities of supra-regional importance as well as numerous other towns are the driving forces of an economically and culturally expanding European region. In combination with attractive landscapes and outdoor leisure opportunities, centrope is one of Europe’s most vibrant areas to live and work in. Population (in thousands) Area (in sq km) Absolute % of centrope Absolute % of centrope South Moravia 1,151.7 17.4 7,196 16.2 Győr-Moson-Sopron 448.4 6.8 4,208 9.5 Vas 259.4 3.9 3,336 7.5 Burgenland 284.0 4.3 3,965 8.9 Lower Austria 1,608.0 24.3 19,178 43.1 Vienna 1,698.8 25.5 414 0.9 Bratislava Region 622.7 9.3 2,053 4.6 Trnava Region 561.5 8.5 4,147 9.3 centrope 6,634.5 44,500 EU-27 501,104.2 4,403,357 Source: Eurostat, population data of 2010. -

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES Volume 18

The Schüssel Era in Austria Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES Volume 18 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2010 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America. Published and distributed in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe by University of New Orleans Press: Innsbruck University Press: ISBN 978-1-60801-009-7 ISBN 978-3-902719-29-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009936824 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Assistant Editor Ellen Palli Jennifer Shimek Michael Maier Universität Innsbruck Loyola University, New Orleans UNO/Vienna Executive Editors Franz Mathis, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Sándor Kurtán Universität Graz Corvinus University Budapest Peter Berger Günther Pallaver Wirtschaftsuniversität -

Wolfgang Schüssel – Bundeskanzler Regierungsstil Und Führungsverhalten“

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit: „Wolfgang Schüssel – Bundeskanzler Regierungsstil und Führungsverhalten“ Wahrnehmungen, Sichtweisen und Attributionen des inneren Führungszirkels der Österreichischen Volkspartei Verfasser: Mag. Martin Prikoszovich angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 300 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Johann Wimmer Persönliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit, dass ich die vorliegende schriftliche Arbeit selbstständig verfertigt habe und dass die verwendete Literatur bzw. die verwendeten Quellen von mir korrekt und in nachprüfbarer Weise zitiert worden sind. Mir ist bewusst, dass ich bei einem Verstoß gegen diese Regeln mit Konsequenzen zu rechnen habe. Mag. Martin Prikoszovich Wien, am __________ ______________________________ Datum Unterschrift 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Danksagung 5 2 Einleitung 6 2.1 Gegenstand der Arbeit 6 2.2. Wissenschaftliches Erkenntnisinteresse und zentrale Forschungsfrage 7 3 Politische Führung im geschichtlichen Kontext 8 3.1 Antike (Platon, Aristoteles, Demosthenes) 9 3.2 Niccolò Machiavelli 10 4 Strukturmerkmale des Regierens 10 4.1 Verhandlungs- und Wettbewerbsdemokratie 12 4.2 Konsensdemokratie/Konkordanzdemokratie/Proporzdemokratie 15 4.3 Konfliktdemokratie/Konkurrenzdemokratie 16 4.4 Kanzlerdemokratie 18 4.4.1 Bundeskanzler Deutschland vs. Bundeskanzler Österreich 18 4.4.1.1 Der österreichische Bundeskanzler 18 4.4.1.2. Der Bundeskanzler in Deutschland 19 4.5 Parteiendemokratie 21 4.6 Koalitionsdemokratie 23 4.7 Mediendemokratie 23 5 Politische Führung und Regierungsstil 26 5.1 Zusammenfassung und Ausblick 35 6 Die Österreichische Volkspartei 35 6.1 Die Struktur der ÖVP 36 6.1.1. Der Wirtschaftsbund 37 6.1.2.