Mexico Country Handbook This Handbook Provides Basic Reference Information on Mexico, Including Its Geography, History, Governme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPECIFICATION GUIDE 2020 at Ply Gem Residential Solutions, We Make the Products That Make Beautiful Homes

SPECIFICATION GUIDE 2020 At Ply Gem Residential Solutions, we make the products that make beautiful homes. PLY GEM RESIDENTIAL SOLUTIONS' PRODUCTS LEAD THE INDUSTRY #1 Vinyl Siding in North America #1 Aluminum Accessories in the U.S. #1 Vinyl & Aluminum Windows in the U.S. #2 Overall Windows in the U.S. #3 Fence & Railing in North America Table of Contents Cedar Dimensions™ Siding . 4 – 8 Vinyl Siding Collection . 9 – 13 Dimensions® . 9 Progressions® . 10 Transformations® . 12 Colonial Beaded . 13 Board & Batten . 13 Vinyl Soffit . 14 – 20 Hidden Vent . 14 Beaded . 15 Premium . 16 Standard . 18 Economy . 19 Vinyl Siding & Soffit Accessories . 21 – 30 Designer Accents . 31 – 60 Mounting Blocks . 31 Surface Mounts . 36 Vents . 38 2-Piece Gable Vents . 41 Board & Batten Shutters . 45 12" Standard Shutters . 49 15" Standard Shutters . 51 Standard Shutter Accessories . 54 Custom Shutters . 55 Window Mantels . 56 Door Surround Systems . 59 Designer Accents Color Matrix . 61 – 81 Aluminum Products . 82 – 108 Trim Coil . 82 Soffit . 97 Fascia . 103 Accessories . 106 Gutter Protection Systems . 109 – 115 Leaf Relief ® . 109 Leaf Logic® & Accessories . 115 Roofing Accessories . 116 – 124 Steel Siding . 125 – 132 Specifications & Conformance . 133 – 135 3 Cedar Dimensions TM D7" Shingle Siding Product Code: CEDAR7 Description Package Nominal .090" Thick 10 Pcs ./Ctn . Length: Double 7" 1/2 Sqs ./Ctn . 40 Lbs ./Ctn . Color Availability WHITE White (04) LIGHT Beige (NB), Pewter (NP), Sand (M4), Sunrise Yellow (IQ), Wicker (A7) CLASSIC French Silk (210), -

Kokkalo Menu

salads Quinoa* with black-eyed beans (V++) (*superfood) €6,90 Chopped leek, carrot, red sweet pepper, spring onion, orange fillet, and citrus sauce "Gaia" (Earth) (V+) €7,90 Green and red verdure, iceberg, rocket, beetroots, blue cheese, casious, orange fillet and orange dressing "Summer Pandesia" (V+) €9,90 Green and red verdure, iceberg, rocket, peach fillet, gruyere cheese, dry figs, nuts, molasses, and honey balsamic dressing Santorinian Greek salad (V+) €8,90 Cherry tomatoes, feta cheese, barley bread bites, onion, cucumber, caper and extra virgin olive oil Cretan "Dakos" (V+) €7,50 Rusk with chopped tomato, olive pate, caper Cretan "xinomitzythra" soft cheese and extra virgin olive oil starters from the land Smoked eggplant dip (V++) €4,90 Pine nut seeds, pomegranate, and extra virgin olive oil Tzatziki dip (V+) €3,50 Greek yogurt with carrot, cucumber, garlic and extra virgin olive oil Soft feta cheese balls (V+) €5,50 Served on sundried tomato mayonaise Freshly cut country style potato fries (V++) €3,90 Sereved on a traditional bailer Bruschetta of Cypriot pitta bread with mozzarella and tomato (V+)€4,90 Topped with tomato spoon sweet and fresh basil Santorini's tomato fritters (V++) €4,50 Served with tzatziki dip (V+) Fried spring rolls stuffed with Santorinian sausage and cheese €4,70 Served with a dip of our home-made spicy pepper sauce Fried zucchini sticks (V++) €5,90 Served with tzatziki dip (V+) Variety of muschrooms with garlic in butter lemon sauce (V+) €4,90 Feta cheese in pie crust, topped with cherry-honey (V+) €6,90 -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Aegean Secrets Welcome

. Aegean Secrets The recipes you are about to try have been passed on to modern Aegean Island Cuisine by countless generations, with secrets and recipes exchanged from mother to daughter since the Neolithic era. Please take the time to use all of your senses while enjoying the unique, ancient flavors and aromas of the Aegean Islands that we are sharing with you today. Καλή Όρεξη, Chef Argiro Barbarigou. Welcome ~ SALATOURI ~ Fish salad with a lemon and herb sauce Upon returning from a long fishing trip, fishermen would rest in a traditional «Καφενίων» (Traditional Mezze establishment) and would regale their comrades over a plate of «Σαλατούρι». ~ FAVA (VEGAN) ~ Fava bean puree served with caramelized onions, capers, olives and e.v.olive oil One of the oldest dishes served in the Aegean, Fava beans have been uncovered in Santorini excavations dating as far back as 3000 B.C. Greek families consider it a staple food and serve it at least once a week. ~ HTYPITI (LACTO VEGETARIAN) ~ Spicy Feta cheese spread with sun-dried peppers served on pita bread with e.v.o oil. Feta cheese, has been manufactured in Greece since before the ancient Greeks with its creation attributed in the Odyssey to Polyphemus the famous cyclops that Odysseus tricks! This same meal without the peppers can be made with a variety of herbs. Wine Pairing: Kir Yianni Sparkling Rose 2016 Aegean Heritage Flavors ~ NTOMATOSALATA & FOUSKOTI (LACTO VEGETARIAN) ~ Tomato salad with black eyed beans, caper leaves, «Κρίταμο» (samphire), Cycladic fresh cheese, E.V. olive oil and oregano. Served with FOUSKOTI a traditional island bread with mastic, saffron, anise and flax seeds. -

Crown Pacific Fine Foods 2019 Specialty Foods

Crown Pacific Fine Foods 2019 Specialty Foods Specialty Foods | Bulk Foods | Food Service | Health & Beauty | Confections Crown Pacific Fine Foods Order by Phone, Fax or Email 8809 South 190th Street | Kent, WA 98031 P: (425) 251-8750 www.crownpacificfinefoods.com | www.cpff.net F: (425) 251-8802 | Toll-free fax: (888) 898-0525 CROWN PACIFIC FINE FOODS TERMS AND CONDITIONS Please carefully review our Terms and Conditions. By ordering SHIPPING from Crown Pacific Fine Foods (CPFF), you acknowledge For specific information about shipping charges for extreme and/or reviewing our most current Terms and Conditions. warm weather, please contact (425) 251‐8750. CREDIT POLICY DELIVERY Crown Pacific Fine Foods is happy to extend credit to our You must have someone available to receive and inspect customers with a completed, current and approved credit your order. If you do not have someone available to receive your application on file. In some instances if credit has been placed order on your scheduled delivery day, you may be subject to a on hold and/or revoked, you may be required to reapply for redelivery and/or restocking fee. credit. RETURNS & CREDITS ORDER POLICY Please inspect and count your order. No returns of any kind When placing an order, it is important to use our item number. without authorization from your sales representative. This will assure that you receive the items and brands that you want. MANUFACTURER PACK SIZE AND LABELING Crown Pacific Fine Foods makes every effort to validate To place an order please contact our Order Desk: manufacturer pack sizes as well as other items such as Phone: 425‐251‐8750 labeling and UPC’s. -

From Southern Nicaragua (Amphibia, Caudata, Plethodontidae)

319 Senckenbergiana biologica | 88 | 2 | 319–328 | 7 figs., 1 tab. | Frankfurt am Main, 19. XII. 2008 Two new species of salamanders (genus Bolitoglossa) from southern Nicaragua (Amphibia, Caudata, Plethodontidae) JAVIER SUNYER, SEBASTIAN LOTZKAT, ANDREAS HERTZ, DAVID B. WAKE, BILLY M. ALEMÁN, SILVIA J. ROBLETO & GUNTHER KÖHLER Abstract We describe two new species of Bolitoglossa from Nicaragua. Bolitoglossa indio n. sp. (holo- type ♀: SMF 85867) is known from Río Indio, in the lowlands of the Río San Juan area, southeast- ern Nicaragua. Bolitoglossa insularis n. sp. (holotype ♀: SMF 87175) occurs on the premontane slopes of Volcán Maderas on Ometepe Island, southwestern Nicaragua. The new species are of unknown affinities but both differ from their congeners in colouration. K e y w o r d s : Bolitoglossa indio n. sp.; Bolitoglossa insularis n. sp.; Central America; Om- etepe island; Río Indio; Río San Juan; Rivas; taxonomy; Maderas Volcano. Zwei neue Salamanderarten (Gattung Bolitoglossa) aus Süd-Nicaragua (Amphibia, Caudata, Plethodontidae) Zusammenfassung: Wir beschreiben zwei neue Arten der Gattung Bolitoglossa aus Nicaragua. Bolitoglossa indio n. sp. (Holotypus ♀: SMF 85867) wurde am Río Indio, im Río San Juan-Tiefland im Südosten Nicaraguas gefunden. Bolitoglossa insularis n. sp. (Holotypus ♀: SMF 87175) stammt aus dem Prämontanwald an den Hängen des Vulkanes Maderas auf der Insel Ometepe im Südwesten Nicaraguas.eschweizerbartxxx sng-Beide neuen Arten lassen sich von ihren nächsten Verwandten anhand ihrer Färbung unterscheiden. Authors’ addresses: Lic. Javier SUNYER, Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, D-60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; [email protected] — also: Institute for Ecology, Evolution and Diversity, BioCampus Westend, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Siesmayerstrasse 70, D-60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany — also: Gabinete de Ecología y Medio Ambiente, Departamento de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua-León (UNAN-León), León, Nicaragua. -

World of Wheels Country Entry

BELGIUM Flag description: three equal vertical bands of black (hoist side), yellow, and red note: the design was based on the flag of France. Background: Belgium became independent from the Neth- erlands in 1830; it was occupied by Germany during World Wars I and II. It has prospered in the past half century as a modern, technologically advanced European state and mem- ber of NATO and the EU. Tensions between the Dutch- speaking Flemish of the north and the French-speaking Wal- loon of the south have led in recent years to constitutional amendments granting these regions formal recognition and autonomy. Geography Belgium. Location: Western Europe, bordering the North Sea, between France and the Netherlands. Area: total: 30,528 sq. km. Area - comparative: about the size of Maryland. Land boundaries: total: 1,385 km. Border coun- tries: France 620 km, Germany 167 km, Luxembourg 148 km, Netherlands 450 km. Coastline: 66.5 km. Climate: tem- perate; mild winters, cool summers; rainy, humid, cloudy. Terrain: flat coastal plains in northwest, central rolling hills, rugged mountains of Ardennes Forest in southeast. Natural resources: construction materials, silica sand, carbonate. Natural hazards: flooding is a threat along rivers and in areas of reclaimed coastal land, protected from the sea by concrete dikes. Environment - current issues: the environment is exposed to intense pressures from human activities: urbanization, dense transportation network, industry, extensive anim- al breeding and crop cultivation; air and water pollution also have repercussions for neighboring coun- tries; uncertainties regarding federal and regional responsibilities (now resolved) have slowed pro- gress in tackling environmental challenges. -

Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Channel Islands National Park Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006 Tim Hauf, www.timhaufphotography.com Foxes Returned to the Wild Full Circle In OctobeR anD nOvembeR 2004, The and November 2004, an additional 13 island Chumash Cross Channel in Tomol to Santa Cruz Island National Park Service (NPS) released 23 foxes on Santa Rosa and 10 on San Miguel By Roberta R. Cordero endangered island foxes to the wild from were released to the wild. The foxes will be Member and co-founder of the Chumash Maritime Association their captive rearing facilities on Santa Rosa returned to captivity if three of the 10 on The COastal portion OF OuR InDIg- and San Miguel Islands. Channel Islands San Miguel or five of the 13 foxes on Santa enous homeland stretches from Morro National Park Superintendent Russell Gal- Rosa are killed or injured by golden eagles. Bay in the north to Malibu Point in the ipeau said, “Our primary goal is to restore Releases from captivity on Santa Cruz south, and encompasses the northern natural populations of island fox. Releasing Island will not occur this year since these Channel Islands of Tuqan, Wi’ma, Limuw, foxes to the wild will increase their long- foxes are thought to be at greater risk be- and ‘Anyapakh (San Miguel, Santa Rosa, term chances for survival.” cause they are in close proximity to golden Santa Cruz, and Anacapa). This great, For the past five years the NPS has been eagle territories. -

Forest Health Through Silviculture

United States Agriculture Forest Health Forest Service Rocky M~untain Through Forest and Ranae Experiment ~taiion Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 Silviculture General ~echnical Report RM-GTR-267 Proceedings of the 1995 National Silviculture Workshop Mescalero, New Mexico May 8-11,1995 Eskew, Lane G., comp. 1995. Forest health through silviculture. Proceedings of the 1945 National Silvidture Workshop; 1995 May 8-11; Mescalero, New Mexico. Gen. Tech; Rep. RM-GTR-267. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 246 p. Abstract-Includes 32 papers documenting presentations at the 1995 Forest Service National Silviculture Workshop. The workshop's purpose was to review, discuss, and share silvicultural research information and management experience critical to forest health on National Forest System lands and other Federal and private forest lands. Papers focus on the role of natural disturbances, assessment and monitoring, partnerships, and the role of silviculture in forest health. Keywords: forest health, resource management, silviculture, prescribed fire, roof diseases, forest peh, monitoring. Compiler's note: In order to deliver symposium proceedings to users as quickly as possible, many manuscripts did not receive conventional editorial processing. Views expressed in each paper are those of the author and not necessarily those of the sponsoring organizations or the USDA Forest Service. Trade names are used for the information and convenience of the reader and do not imply endorsement or pneferential treatment by the sponsoring organizations or the USDA Forest Service. Cover photo by Walt Byers USDA Forest Service September 1995 General Technical Report RM-GTR-267 Forest Health Through Silviculture Proceedings of the 1995 National Silviculture Workshop Mescalero, New Mexico May 8-11,1995 Compiler Lane G. -

Trees of Somalia

Trees of Somalia A Field Guide for Development Workers Desmond Mahony Oxfam Research Paper 3 Oxfam (UK and Ireland) © Oxfam (UK and Ireland) 1990 First published 1990 Revised 1991 Reprinted 1994 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 0 85598 109 1 Published by Oxfam (UK and Ireland), 274 Banbury Road, Oxford 0X2 7DZ, UK, in conjunction with the Henry Doubleday Research Association, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, UK Typeset by DTP Solutions, Bullingdon Road, Oxford Printed on environment-friendly paper by Oxfam Print Unit This book converted to digital file in 2010 Contents Acknowledgements IV Introduction Chapter 1. Names, Climatic zones and uses 3 Chapter 2. Tree descriptions 11 Chapter 3. References 189 Chapter 4. Appendix 191 Tables Table 1. Botanical tree names 3 Table 2. Somali tree names 4 Table 3. Somali tree names with regional v< 5 Table 4. Climatic zones 7 Table 5. Trees in order of drought tolerance 8 Table 6. Tree uses 9 Figures Figure 1. Climatic zones (based on altitude a Figure 2. Somali road and settlement map Vll IV Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following organisations and individuals: Oxfam UK for funding me to compile these notes; the Henry Doubleday Research Association (UK) for funding the publication costs; the UK ODA forestry personnel for their encouragement and advice; Peter Kuchar and Richard Holt of NRA CRDP of Somalia for encouragement and essential information; Dr Wickens and staff of SEPESAL at Kew Gardens for information, advice and assistance; staff at Kew Herbarium, especially Gwilym Lewis, for practical advice on drawing, and Jan Gillet for his knowledge of Kew*s Botanical Collections and Somalian flora. -

Lider Firmy Rodzinnej

ISSN 2353–6470 MAGAZYN FIRM RODZINNYCH Nr 7 (15), grudzień 2015 LIDER FIRMY RODZINNEJ DARIUSZ JASIŃSKI ALICJA HADRYŚ ‑NOWAK MAGDALENA DAROWSKA Prezes firmy i sędzia siatkówki. Liderki Ocena Projektu Lider? Firmy Rodzinne 2 FIRMAFIRMA RODZINNA RODZINNA TO TO MARKA MARKA2 SPIS TREŚCI FIRMAFIRMAFIRMA RODZINNA RODZINNARODZINNA TO TOTO MARKA MARKAMARKAFIRMA RODZINNA TO MARKA TEMAT NUMERU 4 Arkadiusz Zawada Folwark, delfiny i konie strzygące uszami 6 Wiesława Machalica Zostać przywódcą czy być zarządcą? iłość MMiłośćiłość RELACJE. Magazyn Firm Rodzinnych 8 Aleksandra Jasińska ‑Kloska MMMiłośćiłośćiłość M dwumiesięcznik, nr 7 (15), grudzień 2015 Stając się liderem. Nie tylko dla sukcesorów ISSN 2353–6470 10 Dariusz Jasiński wangarda biznesuWydawca: Prezes firmy i sędzia siatkówki. Lider? wangardawangarda biznesubiznesu Awangarda biznesu AAwangarda biznesu Stowarzyszenie AAAwangarda biznesu 11 Agnieszka Szwejkowska Inicjatywa Firm Rodzinnych ul. Smolna 14 m. 7 Lider i współczesne czasy – co jest możliwe? 00–375 Warszawa 12 Wojciech Popczyk ecepta na zmienną rzeczywistość ReceptaRecepta na zmiennąna zmiennąwww.firmyrodzinne.pl rzeczywistość rzeczywistość Kompetencje przywódcze przedsiębiorcyR rodzinnegoRReceptaeceptaecepta na nana zmienną zmiennązmienną rzeczywistość rzeczywistośćrzeczywistość R Redaktor naczelna: 14 Marietta Lewandowska Maria Adamska Czy liderowanie musi być trudne? Spojrzenie młodego pokolenia 16 Alicja Hadryś ‑Nowak reatywność Kreatywnośćreatywność Kontakt: KKreatywnośćreatywnośćreatywność K K Liderki K [email protected] -

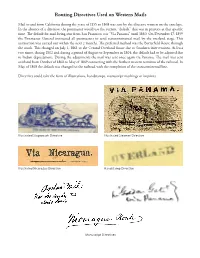

Routing Directives Used on Western Mails

Routing Directives Used on Western Mails Mail to and from California during the years of 1855 to 1868 was sent by the directive written on the envelope. In the absence of a directive, the postmaster would use the current “default” that was in practice at that specific time. The default for mail being sent from San Francisco was “Via Panama” until 1860. On December 17, 1859 the Postmaster General instructed all postmasters to send transcontinental mail by the overland stage. This instruction was carried out within the next 2 months. The preferred method was the Butterfield Route through the south. This changed on July 1, 1861 to the Central Overland Route due to Southern interventions. At least two times, during 1862 and during a period of August to September in 1864, the default had to be adjusted due to Indian depredations. During the adjustments the mail was sent once again via Panama. The mail was sent overland from October of 1868 to May of 1869 connecting with the farthest western terminus of the railroad. In May of 1869 the default was changed to the railroad with the completion of the transcontinental line. Directives could take the form of illustrations, handstamps, manuscript markings or imprints. Illustrated Stagecoach Directive Illustrated Steamer Directive Illustrated Nicaragua Directive Handstamp Directive Manuscript Directives Via Panama - Directives Mail was carried by the US Mail Steamship Co. (between NY and Chagres) and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co (between Panama and San Francisco). Carriage across the isthmus of Panama was by railroad. This was the default method of mail carriage until December 17, 1859.