KERNOW and the KINGDOM of KERNOW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

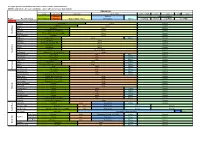

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Age for Daniela Urem's Ancestors Back to Charts

Geni - Ancestors 2/21/17, 2:34 Daniela Urem ▾ Search People 0 Geni Basic Home Tree Family ▾ Research ▾ PRO Upgrade Age for Daniela Urem's Ancestors Back to charts Select a Chart to View Age Click a region on the chart to view Chart: the profiles in that section. Life Expectancy This chart is based on 2681 Group: profiles with lifespan entered for Ancestors your Ancestors. Your tree has 2318 profiles with Slice: missing lifespan data. Make this All chart data chart better by adding missing data. View Profiles Edit Profiles 581-600 of 2681 people «Previous 1 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 135 Next» Photo Name Relationship Managed By Immediate Family Gender Birth Date Daughter of Edward I "The Elder", King of the Anglo-Saxons and Ælfflæd Eadgyth MP Wife of Otto I, Holy (908 - 946) Roman emperor "Princess Edith of Mother of Liudolf, Duke of England", Swabia; Liutgarde and "Edgitha", Richlint von Sachsen, "Editha", "Edith", Herzogin von Schwaben your 32nd great Sister of Aelfgifu between 908 "Ēadgȳð", Erin Spiceland Female grandmother AElfgar's wife of England; and 1/910 "Eadgyth", Eadwin; Æthelflæda, nun "Ēadgith", "Ædgyth", at Romsey; Ælfweard, "Ēadgy", king of the English and 5 "Eadgdith", "Edit others av England" Half sister of Æthelstan 'the Glorious', 1st King of the English; Ælfred; N.N.; Eadburgha, Nun at Nunnaminster and 3 others Daughter of Aëpa II, Khan of the Kumans and N.N. Wife of Yuri I Vladimirovich Dolgorukiy N.N. Aepovna, (the Long Arm) Kuman Princess Mother of Andrei I MP (c.1092 - your 28th great Bogolyubsky; Rostislav Bjørn P. -

The Distribution of Ammonium in Granites from South-West England

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 145, 1988, pp. 37-41, 1 fig., 5 tables. Printed in Northern Ireland The distribution of ammonium in granites from South-West England A. HALL Department of Geology, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX, UK Abstract: The ammonium contents of granites, pegmatites and hydrothermally altered rocks from SW England have been measured. Ammonium levels in the granites are generally high compared with those from other regions, averaging 36ppm,and they differ markedlybetween intrusions. The pegmatites show higherammonium contents than any other igneous rocks which have yet been investigated. Ammonium contents are strongly enriched in the hydrothermally altered rocks, includ- ing greisens and kaolinized granites. There is agood correlation between the average ammonium content of the intrusions in SW England and their initial "Sr/*'Sr ratios and peraluminosity. This relationship supports the hypothesis that the ammonium in the granites is derived from a sedimentary source, either in the magmatic source region or via contamination of the magma. Introduction Results Ammonium is present as a trace constituent of granitic The granites rocks, in which it occurs in feldspars and micas substituting isomorphously for potassium (Honma & Itihara 1981). The The new analyses of Cornubian granites are given in Table amount of ammonium in granites varies from zero to over 1. They show a range of 3-179 parts per million NH:, with 100 parts per million, and it has been suggested that high the highest values being found in relatively small intrusions. concentrations may indicate the incorporation of organic- Taking the averagefor each of the major intrusions,and rich sedimentary material into the magma, either from the weighting them according to their relative areas (see Table presence of such material in rhe magmatic source region or 4), the average ammonium contentof the Cornubian granites via the assimilation of organic-rich country rocks (Urano as a whole is 36 ppm. -

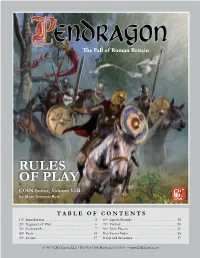

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

The Early Medieval Period, Its Main Conclusion Is They Were Compiled at Malmesbury

Early Medieval 10 Early Medieval Edited by Chris Webster from contributions by Mick Aston, Bruce Eagles, David Evans, Keith Gardner, Moira and Brian Gittos, Teresa Hall, Bill Horner, Susan Pearce, Sam Turner, Howard Williams and Barbara Yorke 10.1 Introduction raphy, as two entities: one “British” (covering most 10.1.1 Early Medieval Studies of the region in the 5th century, and only Cornwall by the end of the period), and one “Anglo-Saxon” The South West of England, and in particular the three (focusing on the Old Sarum/Salisbury area from the western counties of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, later 5th century and covering much of the region has a long history of study of the Early Medieval by the 7th and 8th centuries). This is important, not period. This has concentrated on the perceived “gap” only because it has influenced past research questions, between the end of the Roman period and the influ- but also because this ethnic division does describe (if ence of Anglo-Saxon culture; a gap of several hundred not explain) a genuine distinction in the archaeological years in the west of the region. There has been less evidence in the earlier part of the period. Conse- emphasis on the eastern parts of the region, perhaps quently, research questions have to deal less with as they are seen as peripheral to Anglo-Saxon studies a period, than with a highly complex sequence of focused on the east of England. The region identi- different types of Early Medieval archaeology, shifting fied as the kingdom of Dumnonia has received detailed both chronologically and geographically in which issues treatment in most recent work on the subject, for of continuity and change from the Roman period, and example Pearce (1978; 2004), KR Dark (1994) and the evolution of medieval society and landscape, frame Somerset has been covered by Costen (1992) with an internally dynamic period. -

Art. IIL—The PEOPLES of ANCIENT SCOTLAND

(60) Art. IIL—the PEOPLES OF ANCIENT SCOTLAND. Being the Fourth Rhind Lecture. this lecture it is proposed to make an attempt to under- IN stand the position of the chief peoples beyond the Forth at the dawn of the history of this country, and to follow that down sketchil}' to the organization of the kingdom of Alban. This last part of the task is not undertaken for its own sake, or for the sake of writing on the history of Scotland, which has been so ably handled by Dr. Skene and other historians, of whom you are justly proud, but for the sake of obtaining a comprehensive view of the facts which that history offers as the means of elucidating tlie previous state of things. The initial difficulty is to discover just a few fixed points for our triangulation so to say. This is especially hard to do on the ground of history, so I would try first the geography of the here obtain as our data the situation country ; and we of the river Clyde and the Firth of Forth, then that of the Grampian ]\Iountains and the Mounth or the high lands, extending across the country from Ben Nevis towards Aberdeen. Coming now more to historical data, one may mention, as a fairly well- defined fact, the position of the Koman vallum between the Firth of Forth and the Clyde, coinciding probably with the line of forts erected there in the 81 it by Agricola year ; and is probably the construction of this vallum that is to be understood by the statements relative to Severus building a wall across the island. -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

WELLINGTON and the WREKIN, Wellington to the Wrekin, One of the Midlands Most Famous Natural SHROPSHIRE Landmarks

An 8 mile circular walk connecting the historic east Shropshire market town of WELLINGTON AND THE WREKIN, Wellington to The Wrekin, one of the Midlands most famous natural SHROPSHIRE landmarks. The journey begins in the centre of medieval Wellington and explores The Ercall (the most northerly of the five hills of the Wrekin range) before following the main track to the summit of its iconic 1334-foot sibling. The trail Strenuous Terrain leaves Wellington following the orange-coloured Buzzard signs indicating the new main route of the long-distance Shropshire Way footpath, which continue all the way to summit of The Wrekin. Returning, the route detours through the town’s Bowring Park and historic Market Square before arriving back at the railway station. 8 miles ADVICE: The heathland atop The Wrekin is a precious landscape that can be easily damaged. Please do not Circular trample on the heather and bilberry and keep dogs on their leads during spring and early summer, when many ground-nesting birds are present. Similarly, the hillfort is 4 hours a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) and visitors are encouraged not to walk on its ramparts. FACILITIES: The walk starts at Wellington rail station, 050419 where tourist information and maps of footpaths in the wider area are available. A cafe is situated on Platform Two and public toilets can be accessed with a key during booking office opening hours. Pay toilets are also located at the adjacent bus station, while free facilities can be found at Wellington Civic Centre in Larkin Way. The route also passes the Red Lion pub on Holyhead Road, while Wellington town centre is home to many catering establishments. -

Ancient Dumnonia

ancient Dumnonia. BT THE REV. W. GRESWELL. he question of the geographical limits of Ancient T Dumnonia lies at the bottom of many problems of Somerset archaeology, not the least being the question of the western boundaries of the County itself. Dcmnonia, Dumnonia and Dz^mnonia are variations of the original name, about which we learn much from Professor Rhys.^ Camden, in his Britannia (vol. i), adopts the form Danmonia apparently to suit a derivation of his own from “ Duns,” a hill, “ moina ” or “mwyn,” a mine, w’hich is surely fanciful, and, therefore, to be rejected. This much seems certain that Dumnonia is the original form of Duffneint, the modern Devonia. This is, of course, an extremely respectable pedigree for the Western County, which seems to be unique in perpetuating in its name, and, to a certain extent, in its history, an ancient Celtic king- dom. Such old kingdoms as “ Demetia,” in South Wales, and “Venedocia” (albeit recognisable in Gwynneth), high up the Severn Valley, about which we read in our earliest records, have gone, but “Dumnonia” lives on in beautiful Devon. It also lives on in West Somerset in history, if not in name, if we mistake not. Historically speaking, we may ask where was Dumnonia ? and who were the Dumnonii ? Professor Rhys reminds us (1). Celtic Britain, by G. Rhys, pp. 290-291. — 176 Papers, §*c. that there were two peoples so called, the one in the South West of the Island and the other in the North, ^ resembling one another in one very important particular, vizo, in living in districts adjoining the seas, and, therefore, in being maritime. -

The Wreki N Hiπfo Rt

and died. and made merry, quarrelled quarrelled merry, made generations have lived, lived, have generations people’s lives; somewhere somewhere lives; people’s has been the centre of of centre the been has of years ago. This place place This ago. years of who lived here thousands thousands here lived who in the footsteps of people people of footsteps the in summit, we are following following are we summit, week. When we walk to its its to walk we When week. clear day. clear these are the events of last last of events the are these in 17 counties on a a on counties 17 in 600 million years ago, ago, years million 600 summit, said to take take to said summit, For the Wrekin, a hill some some hill a Wrekin, the For panorama from the the from panorama in the county with a magnificent magnificent a with county the in introduction of coke. of introduction The Wrekin is the eighth highest summit summit highest eighth the is Wrekin The consider yourself a true Salopian. Salopian. true a yourself consider emerging foundries of Ironbridge, before the the before Ironbridge, of foundries emerging passed through the cleft between the rocks can you you can rocks the between cleft the through passed tending their smoking fuel, highly valued in the the in valued highly fuel, smoking their tending on a stone or scuttling off into the heather. the into off scuttling or stone a on localness; tradition has it that only when you have have you when only that it has tradition localness; charcoal burners moved between several kilns, kilns, several between moved burners charcoal summer you might catch a lizard sunning itself itself sunning lizard a catch might you summer near the summit. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society.