Paper Information: Title: Aspects of Romanization in the Wroxeter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research News Issue 15

NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH HERITAGE RESEARCH DEPARTMENT Inside this issue... RESEARCH Introduction ...............................2 NEW DISCOVERIES AND INTERPRETATIONS NEWS Photo finish for England’s highest racecourse ...................3 Aldborough in focus: air photographic analysis and © English Heritage mapping of the Roman town of Isurium Brigantium ...........6 Recent work at Marden Henge, Wiltshire .................... 10 Manningham: an historic area assessment of a Bradford suburb .................... 14 DEVELOPING METHODOLOGIES English Heritage Coastal Estate Risk Assessment ....... 18 UNDERSTANDING PLACES Understanding place ............ 20 Celebrating People & Place: guidance on commemorative plaques .................................... 22 NOTES & NEWS ................. 23 RESEARCH DEPARTMENT REPORTS LIST ....................... 27 3D lidar model showing possible racecourse on Alston Common, Cumbria – see story page 3 NEW PUBLICATIONS ......... 28 NUMBER 15 AUTUMN 2010 ISSN 1750-2446 This issue of Research News is published soon after the Government’s Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) announcement, which for English Heritage means a cut of 32% to our grant in aid over the next four years from 1st April 2011. On a more positive note the Government sees a continuing role for English Heritage and values the independent expert advice it provides. Research Department staff make an important contribution to the organisation’s expertise. Applied research will continue to be an important part of the role of English Heritage and from April 2011 it will be integrated with our designation, planning and advice functions as part of the National Heritage Protection Plan (NHPP). The Plan, published on our website on the 7th December 2010, will focus our research effort and other activities on those heritage assets that are both significant and under threat. In response to the CSR and the NHPP Research News will, from 2011, be published twice rather than three times a year, and focus on reporting on the range of research activities contributing to the Plan. -

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

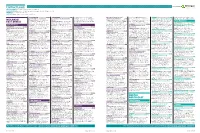

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in Planning up to Detailed Plans Submitted

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in planning up to detailed plans submitted. PLANS APPROVED Projects where the detailed plans have been approved but are still at pre-tender stage. TENDERS Projects that are at the tender stage CONTRACTS Approved projects at main contract awarded stage. NORTHAMPTON £3.7M CHESTERFIELD £1M Detail Plans Granted for 2 luxury houses The Coppice Primary School, 50 County Council Agent: A A Design Ltd, GRIMSBY £1M Studios, Trafalgar Street, Newcastle-Upon- Land Off, Alibone Close Moulton Recreation Ground, North Side New Client: Michael Howard Homes Developer: Shawhurst Lane Hollywood £1.7m Aizlewood Road, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, Grimsby Leisure Centre, Cromwell Road Tyne, Tyne & Wear, NE1 2LA Tel: 0191 2611258 MIDLANDS/ Planning authority: Daventry Job: Outline Tupton Bullworthy Shallish LLP, 3 Quayside Place, Planning authority: Bromsgrove Job: Detail S8 0YX Contractor: William Davis Ltd, Forest Planning authority: North East Lincolnshire Plans Granted for 16 elderly person Planning authority: North East Derbyshire Quayside, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 1FA Tel: Plans Granted for school (extension) Client: Field, Forest Road, Loughborough, Job: Detailed Plans Submitted for leisure Plans Approved EAST ANGLIA bungalows Client: Gayton Retirement Fund Job: Detail Plans Granted for 4 changing 01394 384 736 The Coppice Primary School Agent: PR Leicestershire, LE11 3NS Tel: 01509 231181 centre Client: North East Lincolnshire BILLINGHAM £0.57M & Beechwood Trusteeship & Administration rooms pavilion -

HISTORY of WORFIELD – the EARLIEST SETTLEMENT. Worfield's History Does Not Begin, As Far As We Can Tell, in Worfield Village I

HISTORY OF WORFIELD – THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT. Worfield's history does not begin, as far as we can tell, in Worfield village itself. The earliest evidence for settlement in the Parish is at Chesterton. Today Chesterton is a hamlet but to the South of the village is an iron age hill fort of just over 20 acres. There are two ways of accessing the site, either from Chesterton or from Littlegain. From Chesterton walk towards the B4176 until you reach the last house on your left and just beyond that is a public footpath leading to The Walls. From Littlegain leave your car on the grass verge at the top of the lane and walk down the lane, crossing the Stratford Brook. Look carefully and you will find the path leading to the Walls. There are pros and cons of both approaches. The Littlegain approach can be very muddy and there is a very steep ascent to The Walls but to approach from this direction gives you a good impression of the valley and the steps you take from the valley are thought to date from the iron age period. If you do visit please note that metal detecting and digging are, of course, forbidden. Approaching from either direction you will be using one of the original entrances. As you follow the footpath round you will see earthworks – what an achievement to dig these with the most primitive of tools. Erosion and ploughing have levelled the embankment and ditch on the north side but on the east side the ramparts are very impressive. -

![Lullingstone Roman Villa. a Teacher's Handbook.[Revised]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0520/lullingstone-roman-villa-a-teachers-handbook-revised-380520.webp)

Lullingstone Roman Villa. a Teacher's Handbook.[Revised]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 970 SO 031 609 AUTHOR Watson, lain TITLE Lullingstone Roman Villa. A Teacher's Handbook. [Revised]. ISBN ISBN-1-85074-684-2 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 44p. AVAILABLE FROM English Heritage, Education Service, 23 Savile Row, London W1X lAB, England; Tel: 020 7973 3000; Fax: 020 7973 3443; E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: (www.english-heritage.org.uk/). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archaeology; Foreign Countries; Heritage Education; *Historic Sites; Historical Interpretation; Learning Activities; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *England (Kent); English History; Mosaics; *Roman Architecture; Roman Civilization; Roman Empire; Site Visits; Timelines ABSTRACT Lullingstone, in Kent, England, is a Roman villa which was in use for almost the whole period of the Roman occupation of Britain during the fourth century A.D. Throughout this teacher's handbook, emphasis is placed on the archaeological evidence for conclusions about the use of the site, and there are suggested activities to help students understand the techniques and methods of archaeology. The handbook shows how the site relates to its environment in a geographical context and suggests how its mosaics and wall paintings can be used as stimuli for creative work, either written or artistic. It states that the evidence for building techniques can also be examined in the light of the technology curriculum, using the Roman builder activity sheet. The handbook consists of the following sections: -

WELLINGTON and the WREKIN, Wellington to the Wrekin, One of the Midlands Most Famous Natural SHROPSHIRE Landmarks

An 8 mile circular walk connecting the historic east Shropshire market town of WELLINGTON AND THE WREKIN, Wellington to The Wrekin, one of the Midlands most famous natural SHROPSHIRE landmarks. The journey begins in the centre of medieval Wellington and explores The Ercall (the most northerly of the five hills of the Wrekin range) before following the main track to the summit of its iconic 1334-foot sibling. The trail Strenuous Terrain leaves Wellington following the orange-coloured Buzzard signs indicating the new main route of the long-distance Shropshire Way footpath, which continue all the way to summit of The Wrekin. Returning, the route detours through the town’s Bowring Park and historic Market Square before arriving back at the railway station. 8 miles ADVICE: The heathland atop The Wrekin is a precious landscape that can be easily damaged. Please do not Circular trample on the heather and bilberry and keep dogs on their leads during spring and early summer, when many ground-nesting birds are present. Similarly, the hillfort is 4 hours a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) and visitors are encouraged not to walk on its ramparts. FACILITIES: The walk starts at Wellington rail station, 050419 where tourist information and maps of footpaths in the wider area are available. A cafe is situated on Platform Two and public toilets can be accessed with a key during booking office opening hours. Pay toilets are also located at the adjacent bus station, while free facilities can be found at Wellington Civic Centre in Larkin Way. The route also passes the Red Lion pub on Holyhead Road, while Wellington town centre is home to many catering establishments. -

The Fenemere, Berrington Meadows, Cross Houses, Shrewsbury, SY5 6JJ Asking Price £410,000

The Fenemere, Berrington Meadows, Cross Houses, Shrewsbury, SY5 6JJ Asking Price £410,000 The Fenemere : This luxurious four-bedroom home epitomises the Fletcher Homes’ difference, scoring top marks for kerb appeal and interior layout. The large hallway feeds into a sizeable study and sitting room, which features an inglenook fireplace with wood burning stove included as standard in the Fenemere design. At the rear of the house sits a beautifully designed open plan kitchen, dining and breakfast area, complimented with double French doors opening out to the spacious patio and garden. The Fenemere house is the only house with a combined open plan breakfast area combined with the kitchen, making it our most stylish house. The stairs open up to another lengthy hallway leading to three double bedrooms, two with an en-suite, an added single bedroom, and a family bathroom. All Fenemere plots are built with a double garage and a driveway. For specific plots please see site layout plan. Sq. Ft. 1457. Utility 8' 0'' x 5' 10'' (2.45m x 1.78m) Berrington Meadows, Cross Houses, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 6JJ Study 10' 0'' x 8' 0'' (3.04m x 2.45m) Three and four bedroomed homes. Cloaks Located on the outskirts of Shrewsbury. 5' 6'' x 3' 7'' (1.68m x 1.09m) Underfloor heating to the ground floor First Floor Ultra Fast Fibre broadband, with BT Optical Network Termination Unit (ONT). Master Bedroom Help to buy available. 11' 7'' x 11' 0'' (3.52m x 3.35m) NHBC Building Warranty for 10 years. Ensuite 8' 1'' x 5' 11'' (2.47m x 1.80m) Welcome to Berrington Meadows Bedroom Two We are pleased to introduce Berrington Meadows, 12' 10'' x 10' 10'' (3.91m x 3.30m) comprising of three and four bedroomed homes, located on the outskirts of Shrewsbury. -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Housing and Strategic Planning Portfolio Holder Report

Committee and Date Item Council 19th December 2019 Public HOUSING AND STRATEGIC PLANNING PORTFOLIO HOLDER REPORT MemberCllr Robert Macey e-mail: [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The following report provides Council with an update and briefing on the Housing and Strategic Planning Portfolio over the past twelve months. 1.2 The Portfolio broadly covers the service areas and departments of ‘Housing Services’ and ‘Strategic Planning’; as well as the Council owned companies of ‘Cornovii Developments Limited’ and ‘Shropshire Towns & Rural Housing Limited’ (STaR Housing). 1.3 As this report will demonstrate, it has been a year of significant progress and challenge. One good example to highlight the pace of change and progress made, is that it is only a little over a year ago that a report outlining the unmet housing need in the county was presented. Since then we have established our own local housing company ‘Cornovii Developments Limited’, approved funding for it’s first two developments and are now considering funding for a future development pipeline to further address unmet housing need. 2. RECOMMENDATION 2.1 That Council: Approves the Housing and Strategic Planning Portfolio Holder Report. Page 1 of 12 REPORT 3. HOUSING SERVICES 3.1 Housing Services is a group of interrelated services which includes the Housing Options Service, Private Sector Housing, Shropshire HomePoint and Housing Support. 3.2 Housing Options & Homelessness Service 3.2.1 During 2018/19 there were 1,490 homelessness presentations in Shropshire, of which 1,023 households were assessed as being owed a duty. Further to this there were an additional 1000+ presentations for advice and assistance. -

The Wreki N Hiπfo Rt

and died. and made merry, quarrelled quarrelled merry, made generations have lived, lived, have generations people’s lives; somewhere somewhere lives; people’s has been the centre of of centre the been has of years ago. This place place This ago. years of who lived here thousands thousands here lived who in the footsteps of people people of footsteps the in summit, we are following following are we summit, week. When we walk to its its to walk we When week. clear day. clear these are the events of last last of events the are these in 17 counties on a a on counties 17 in 600 million years ago, ago, years million 600 summit, said to take take to said summit, For the Wrekin, a hill some some hill a Wrekin, the For panorama from the the from panorama in the county with a magnificent magnificent a with county the in introduction of coke. of introduction The Wrekin is the eighth highest summit summit highest eighth the is Wrekin The consider yourself a true Salopian. Salopian. true a yourself consider emerging foundries of Ironbridge, before the the before Ironbridge, of foundries emerging passed through the cleft between the rocks can you you can rocks the between cleft the through passed tending their smoking fuel, highly valued in the the in valued highly fuel, smoking their tending on a stone or scuttling off into the heather. the into off scuttling or stone a on localness; tradition has it that only when you have have you when only that it has tradition localness; charcoal burners moved between several kilns, kilns, several between moved burners charcoal summer you might catch a lizard sunning itself itself sunning lizard a catch might you summer near the summit.