Musical.Ethnicity.Stokes.16.August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Course in International Folk Dance, Harry Khamis, 1994

Table of Contents Preface .......................................... i Recommended Reading/Music ........................iii Terminology and Abbreviations .................... iv Basic Ethnic Dance Steps ......................... v Dances Page At Va'ani ........................................ 1 Ba'pardess Leyad Hoshoket ........................ 1 Biserka .......................................... 2 Black Earth Circle ............................... 2 Christchurch Bells ............................... 3 Cocek ............................................ 3 For a Birthday ................................... 3 Hora (Romanian) .................................. 4 Hora ca la Caval ................................. 4 Hora de la Botosani .............................. 4 Hora de la Munte ................................. 5 Hora Dreapta ..................................... 6 Hora Fetalor ..................................... 6 Horehronsky Czardas .............................. 6 Horovod .......................................... 7 Ivanica .......................................... 8 Konyali .......................................... 8 Lesnoto Medley ................................... 8 Mari Mariiko ..................................... 9 Miserlou ......................................... 9 Pata Pata ........................................ 9 Pinosavka ........................................ 10 Setnja ........................................... 10 Sev Acherov Aghcheek ............................. 10 Sitno Zensko Horo ............................... -

Cover No Spine

2006 VOL 44, NO. 4 Special Issue: The Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2006 The Journal of IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People Editors: Valerie Coghlan and Siobhán Parkinson Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Nina Christensen (Denmark), Penni Cotton (UK), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), Elwyn Jenkins (South Africa),Ariko Kawabata (Japan), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Maria Nikolajeva (Sweden), Jean Perrot (France), Kimberley Reynolds (UK), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Victor Watson (UK), Jochen Weber (Germany) Board of Bookbird, Inc.: Joan Glazer (USA), President; Ellis Vance (USA),Treasurer;Alida Cutts (USA), Secretary;Ann Lazim (UK); Elda Nogueira (Brazil) Cover image:The cover illustration is from Frau Meier, Die Amsel by Wolf Erlbruch, published by Peter Hammer Verlag,Wuppertal 1995 (see page 11) Production: Design and layout by Oldtown Design, Dublin ([email protected]) Proofread by Antoinette Walker Printed in Canada by Transcontinental Bookbird:A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People, Nonnenweg 12 Postfach, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland tel. +4161 272 29 17 fax: +4161 272 27 57 email: [email protected] <www.ibby.org>. Copyright © 2006 by Bookbird, Inc., an Indiana not-for-profit corporation. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Items from Focus IBBY may be reprinted freely to disseminate the work of IBBY. -

First Class Mail PAID

FOLK DANCE SCENE First Class Mail 4362 COOLIDGE AVE. U.S. POSTAGE LOS ANGELES, CA 90066 PAID Culver City, CA Permit No. 69 First Class Mail Dated Material ORDER FORM Please enter my subscription to FOLK DANCE SCENE for one year, beginning with the next published issue. Subscription rate: $15.00/year U.S.A., $20.00/year Canada or Mexico, $25.00/year other countries. Published monthly except for June/July and December/January issues. NAME _________________________________________ ADDRESS _________________________________________ PHONE (_____)_____–________ CITY _________________________________________ STATE __________________ E-MAIL _________________________________________ ZIP __________–________ Please mail subscription orders to the Subscription Office: 2010 Parnell Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90025 (Allow 6-8 weeks for subscription to go into effect if order is mailed after the 10th of the month.) Published by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South Volume 40, No. 1 February 2004 Folk Dance Scene Committee Club Directory Coordinators Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Calendar Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Beginner’s Classes (cont.) On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 Club Time Contact Location Contributing Editor Richard Duree [email protected] (714) 641-7450 CONEJO VALLEY FOLK Wed 7:30 (805) 497-1957 THOUSAND OAKS, Hillcrest Center, Contributing Editor Jatila van der Veen [email protected] (805) 964-5591 DANCERS Jill Lungren 403 W Hillcrest Dr Proofreading Editor Laurette Carlson [email protected] (310) 397-2450 ETHNIC EXPRESS INT'L Wed 6:30-7:15 (702) 732-4871 LAS VEGAS, Charleston Heights Art FOLK DANCERS except holidays Richard Killian Center, 800 S. -

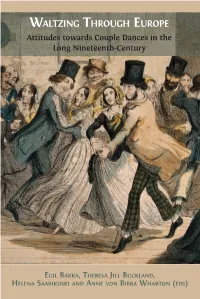

9. Dancing and Politics in Croatia: the Salonsko Kolo As a Patriotic Response to the Waltz1 Ivana Katarinčić and Iva Niemčić

WALTZING THROUGH EUROPE B ALTZING HROUGH UROPE Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the AKKA W T E Long Nineteenth-Century Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the Long Nineteenth-Century EDITED BY EGIL BAKKA, THERESA JILL BUCKLAND, al. et HELENA SAARIKOSKI AND ANNE VON BIBRA WHARTON From ‘folk devils’ to ballroom dancers, this volume explores the changing recep� on of fashionable couple dances in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards. A refreshing interven� on in dance studies, this book brings together elements of historiography, cultural memory, folklore, and dance across compara� vely narrow but W markedly heterogeneous locali� es. Rooted in inves� ga� ons of o� en newly discovered primary sources, the essays aff ord many opportuni� es to compare sociocultural and ALTZING poli� cal reac� ons to the arrival and prac� ce of popular rota� ng couple dances, such as the Waltz and the Polka. Leading contributors provide a transna� onal and aff ec� ve lens onto strikingly diverse topics, ranging from the evolu� on of roman� c couple dances in Croa� a, and Strauss’s visits to Hamburg and Altona in the 1830s, to dance as a tool of T cultural preserva� on and expression in twen� eth-century Finland. HROUGH Waltzing Through Europe creates openings for fresh collabora� ons in dance historiography and cultural history across fi elds and genres. It is essen� al reading for researchers of dance in central and northern Europe, while also appealing to the general reader who wants to learn more about the vibrant histories of these familiar dance forms. E As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the UROPE publisher’s website. -

Published by the Folkdance Federation of California, South Volume 52, No

Published by the Folkdance Federation of California, South Volume 52, No. 4 May 2016 Folk Dance Scene Committee Coordinator Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Calendar Gerri Alexander [email protected] (818) 363-3761 On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 Dancers Speak Sandy Helperin [email protected] (310) 391-7382 Federation Corner Beverly Barr [email protected] (310) 202-6166 Proofreading Editor Jan Rayman [email protected] (818) 790-8523 Carl Pilsecker [email protected] (562) 865-0873 Design and Layout Editors Pat Cross, Don Krotser [email protected] (323) 255-3809 Business Managers Gerda Ben-Zeev [email protected] (310) 399-2321 Nancy Bott Circulation Sandy Helperin [email protected] (310) 391-7382 Subscriptions Gerda Ben-Zeev [email protected] (310) 399 2321 Advertising Steve Himel [email protected] Printing Coordinator Irwin Barr (310) 202-6166 Marketing Bob, Gerri Alexander [email protected] (818) 363-3761 Gerda Ben-Zeev Jill and Jay Michtom 19 Village Park Way Sandy Helperin 10824 Crebs Ave. Santa Monica, CA 90405 4362 Coolidge Ave. Northridge, CA 91326 Los Angeles, CA 90066 Folk Dance Scene Copyright 2016 by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc., of which this is the official publication. All rights reserved. Folk Dance Scene is published ten times per year on a monthly basis except for combined issues in June/July and December/January. First class postage is paid in Los Angeles, CA, ISSN 0430-8751. Folk Dance Scene is published to educate its readers concerning the folk dance, music, costumes, lore and culture of the peoples of the world. -

Nama Drmeš Medley

NAMA DRMEŠ MEDLEY Croatian PRONUNCIATION: NAH-mah DRR-mesh MED-lee TRANSLATION: Medley of three Croatian dances SOURCE: Dick Oakes learned these dances from Dick Crum. BACKGROUND: Drmeš iz Zdenčine, Kriči Kriči Tiček, and Kiša Pada (Posavski Drmeš) are the three "drmeši" (shaking dances) in this medley for which the transitions have been arranged by David Owens, the director of the NAMA Orchestra. Dick Crum, noted folk dance researcher, says that the drmeš, or shaking dance, is the most typical dance form in the northwestern part of Croatia. Drmeši are rarely danced today, except at weddings or other celebrations, and usually only by older dancers, dancing as couples or in small circles of three or four. Otherwise, the drmeš is usually only seen when performed by amateur dance groups who may select a tune and some movements culled from the older dancers for presentation to audiences as living museum pieces. Sometimes, groups from adjacent villages will select different movements and sequences for a particular melody common to both, giving rise to what puzzled American folk dancers sometimes think of as conflicting versions of the same dance. Drmeš iz Zdenčine (DRR-mesh ees SDEHN-chee-neh) comes from the village of Zdenčina, about half-way between Zagreb and Karlovac (near Jastrebarsko). It was collected in 1954 by Dick Crum. Kriči Kriči Tiček (KREE-chee KREE-chee TEE-chek) means "chirp chirp little bird" and originates in the Prigorije district, just north of Zagreb. This dance was also collected by Dick Crum in 1954. Kriči Kriči Tiček is one such dance that has undergone the natural preservative process. -

Christos Papakostas Gaida

LAGUNA FOLKDANCERS FESTIVAL 2013 SYLLABUS Christos Papakostas Gaida .......................................................................3 Gaida Poustseno or Amolyti Gaida................................................4 Hasapia......................................................................5 Karsilamas Aptalikos...........................................................6 Ormanli .....................................................................7 Pat(i)ma.....................................................................8 Pogonisios ...................................................................9 Poustseno...................................................................10 Sirtos & Balos ...............................................................11 Thiakos & Selfo..............................................................12 Željko Jergan Map of Hrvatska (Croatia)......................................................14 Gradiš4e Dances .............................................................15 Igre Bosanske................................................................19 Klin6ek.....................................................................22 Logovac ....................................................................25 Manfrina....................................................................28 Posavski Drmeši..............................................................31 Prosijala....................................................................33 Šoka6ko Kolo................................................................35 -

Derite (Se Čizme Moje)—Not Taught

67 Derite (Se Čizme Moje) —not taught (Burgenland, Austria) During the 16th century Turkish invasion, many Croatians left the regions around the Kupa, Korana and Una rivers, and the region of Primorje, finding safety in a desolate region of Burgenland, Austria, known to the Croatians that live there as Gradišće. They have managed to maintain to this day, their rich traditions, language and culture, including this dance and song from the village Stinatz (Stinjaki), which are done during festive celebrations. The research was done in 1982-84 in Gradišće. Translation: Fall apart, my boots. Pronunciation: deh-REE-teh (seh CHEEZH-meh-MOHY-yeh) Music: 2/4 meter CD: Baština Hrvatskog Sela by Otrov, Band 11. Cassette: Treasury of Croatian Dances by Jerry Grcevich, side A/5; or Croatian Folk Dances by Jerry Grcevich, Vol. II, side A/4. Formation: Cpls in a closed circle, hands in W-pos with middle fingers joined. W on M’s R side. Steps and Buzz step with stamp: Stamp R across L (ct 1); step L fwd on ball of ft (ct 2). When Styling: doing buzz steps, stamp when stepping on R ft. Part I: Heavy drmeš with stamping to accent the first beat and bouncy. Part II: Bouncy and light. Part III: Smooth gliding buzz steps. Meas Music: 2/4 meter Pattern 6 meas INTRODUCTION I. DRMEŠ 1 Facing ctr and dancing in place, stamp R very slightly to R (ct 1); hop on R, 2 times, as ball of L ft touches in front of R (cts 2,&) (SQQ rhythm). 2-6 Repeat meas 1, alternating ftwk and direction. -

BALKANISMS M M Guitar Music from the Balkans 4

N N A A X The area in south-east europe known as the Balkans has long established folk traditions X O O S rich in complex rhythms and evocative melodies. Innovative guitarist Mak Grgi ć has se - S lected the music of five composers to explore the variety and piquant colours embedded in their compositions. Drawn from his evolving suite called Laments, Dances and Lullabies , B B Miroslav Tadić traces Macedonian folk songs, while each of the other composers brings 8.573920 A A very personal qualities. Vivid harmonies, vivacious interludes, syncopated rhythms, and a L L DDD K K lively, jazz-like feel all combine to create a tapestry of moods and textures. A A Playing Time N N 7 I I 76:03 S S BALKANISMS M M Guitar music from the Balkans 4 ! 7 S S 3 : : Allegretto comodo 3:38 Miroslav TADIĆ (b. 1959) 1 1 G G 2 Jovk a* (2017) 2:35 3 Vojislav IVANOVIĆ (b. 1959) u u 3 Chich o* (2016) 5:38 9 i i @ Café Pieces (1993) (excerpts) 18:29 t t 2 a a Improvisation and Dance 6:03 # 0 Dušan BOGDANOVIĆ (b. 1955) r r 7 $ A Funny Valse 5:07 Levantine Suite (1995) 11:27 m m 3 A Lullaby 7:14 Prelude 1:24 u u 4 0 s s 5 Dance 1:42 Lazar OSTOJIĆ (b. 1987) i i % B M w ൿ c c o Cantilena 3:33 6 a Stairway to the Balkan s* w o & d f f k e r Passacaglia 2:58 r 7 l Ꭿ w (2017) 12:52 e i o o n t Postlude 1:36 . -

BORN, Western Music

Western Music and Its Others Western Music and Its Others Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music EDITED BY Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London All musical examples in this book are transcriptions by the authors of the individual chapters, unless otherwise stated in the chapters. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2000 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Western music and its others : difference, representation, and appropriation in music / edited by Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-520-22083-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—isbn 0-520--22084-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Music—20th century—Social aspects. I. Born, Georgina. II. Hesmondhalgh, David. ml3795.w45 2000 781.6—dc21 00-029871 Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 10987654321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). 8 For Clara and Theo (GB) and Rosa and Joe (DH) And in loving memory of George Mully (1925–1999) CONTENTS acknowledgments /ix Introduction: On Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music /1 I. Postcolonial Analysis and Music Studies David Hesmondhalgh and Georgina Born / 3 II. Musical Modernism, Postmodernism, and Others Georgina Born / 12 III. Othering, Hybridity, and Fusion in Transnational Popular Musics David Hesmondhalgh and Georgina Born / 21 IV. Music and the Representation/Articulation of Sociocultural Identities Georgina Born / 31 V. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles From

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles From Community to Humanity: Dance as Intangible Cultural Heritage A dissertation completed in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Filip Petkovski 2021 © Copyright by Filip Petkovski 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION From Community to Humanity: Dance as Intangible Cultural Heritage by Filip Petkovski Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Anurima Banerji, Co-Chair Professor Janet O’Shea, Co-Chair Abstract My dissertation project examines the gradual phases of recontextualizing, folklorizing, heritagizing, and choreographing dance in Macedonia, Serbia, and Croatia, and in the Former Yugoslavia in general. In order to demonstrate how dance becomes intangible cultural heritage, I combine UNESCO archival materials with ethnographic research and interviews with dancers, choreographers, and heritage experts. While I trace how the discourses around folklore and intangible cultural heritage were used in the construction of the Yugoslav, and later in the post- Yugoslav nation states, I also write about the hegemonic relationship between dance and institutions. I emphasize dance as a vehicle for mediating ideas around authenticity, distinctiveness, and national identity, while also acknowledging how the UNESCO process of safeguarding and listing culture allows countries such as Macedonia, Serbia, and Croatia to achieve international recognition. By studying the relationship between dance, archives, and UNESCO conventions, we can understand the intersection between institutions and issues ii around nationalism, but also how discourses of dance shifted dance production and reception in various historical and political contexts during and after the existence of the Yugoslav state. -

Salt Spring Island Folk Dance Festival by Maya Trost and Mirdza Jaunzemis

Salt Spring Island Folk Dance Festival By Maya Trost and Mirdza Jaunzemis On April 27, 2012, three of us, members of OFDA, and Sunday. Chef Kelly Kelsick and his crew of five arrived at the ninth annual Salt Spring Island Folk did all the cooking for the lunches and dinner on Dance Festival in British Columbia. For Mirdza and Saturday. Cusheon Lake resort made a monetary Maya it was the first time at this festival, but Helen donation and offered discounts on cabin rentals. Griffin had attended two years earlier. Having only Rosemarie’s son and a friend took on the task of Ontario Folk Dance Camp and Mainewoods as carting away and washing all the dishes and pots. comparisons, we found the festival quite different. Usually the spouses of those performing organizational tasks get involved in helping out as The festival is held at Fulford Hall, a community well. Local musician, singer and songwriter Harry centre at Fulford Harbour. Festival registrants are Warner was invited to entertain us by singing one of responsible for booking their own accommodation at his songs, “From Galway to Salt Spring.” one of the many B&Bs, cottages or motels, depending on availability and their budget. The dance teachers were Željko Jergan teaching Croatian dances, and Richard Schmidt teaching The founder and “CEO” is Rosemarie Keough Polish dances. Live music was provided during the (who danced at IFDC in Toronto from 1981 to 1984), weekend by the Washington-based Kafana Republik a dynamic, professional woman (photographer and band. publisher), who organizes this event in her “spare time.” The 10th anniversary of the festival will be celebrated As a special surprise the Polish folk group the in 2013, and teachers Yves Moreau, France Bourque- White Eagle Band of Victoria came over by ferry to Moreau and Iliana Bozhanova with accordionist Todor entertain us during lunch on Saturday and stayed long Yankov have been booked for April 26–28.