UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Course in International Folk Dance, Harry Khamis, 1994

Table of Contents Preface .......................................... i Recommended Reading/Music ........................iii Terminology and Abbreviations .................... iv Basic Ethnic Dance Steps ......................... v Dances Page At Va'ani ........................................ 1 Ba'pardess Leyad Hoshoket ........................ 1 Biserka .......................................... 2 Black Earth Circle ............................... 2 Christchurch Bells ............................... 3 Cocek ............................................ 3 For a Birthday ................................... 3 Hora (Romanian) .................................. 4 Hora ca la Caval ................................. 4 Hora de la Botosani .............................. 4 Hora de la Munte ................................. 5 Hora Dreapta ..................................... 6 Hora Fetalor ..................................... 6 Horehronsky Czardas .............................. 6 Horovod .......................................... 7 Ivanica .......................................... 8 Konyali .......................................... 8 Lesnoto Medley ................................... 8 Mari Mariiko ..................................... 9 Miserlou ......................................... 9 Pata Pata ........................................ 9 Pinosavka ........................................ 10 Setnja ........................................... 10 Sev Acherov Aghcheek ............................. 10 Sitno Zensko Horo ............................... -

Stability and Change in Rhythmic Patterning Across a Composer's

Stability and Change in Rhythmic Patterning Across a Composer’s Lifetime: A Study of Four Famous Composers Using the nPVI Equation Joseph R. Daniele & Aniruddh D. Patel Figures 2, 3, and 4 of are displayed within this paper in grayscale. See print color plate for color versions of these figures. For direct embedding of the color figures, refer to the PDF online at http://mp.ucpress.edu/ 256 Joseph R. Daniele & Aniruddh D. Patel STABILITY AND CHANGE IN RHYTHMIC PATTERNING ACROSS A COMPOSER’S LIFETIME:ASTUDY OF FOUR FAMOUS COMPOSERS USING THE NPVI EQUATION JOSEPH R. DANIELE of German and Austrian instrumental classical music University of California, Berkeley between *1600 and 1950. Analyzing 3,195 themes from 21 composers, we found that the average degree ANIRUDDH D. PATEL of durational contrast between notes in musical themes Tufts University (as measured by the normalized pairwise variability index, or nPVI) increased steadily over historical time, HISTORICAL TRENDS IN THE RHYTHM OF WESTERN a trend not seen in Italian classical music during this European instrumental classical music between *1650 same time period. This finding proved relevant to ideas and 1950 have recently been studied using the nPVI in historical musicology regarding the changing influ- equation. This equation measures the average degree ence of Italian music on Austro-German classical music of durational contrast between adjacent events in (see Daniele & Patel, 2013, for details). Our findings a sequence (such as notes in a musical theme). These were based on assigning each composer a single nPVI historical studies (e.g., Daniele & Patel, 2013, Hansen value, representing the mean nPVI of his themes from A et al., in press) have relied on assigning each composer’s Dictionary of Musical Themes (Barlow & Morgenstern, music a mean nPVI value in order to search for broad 1983). -

MP3502 04 Temperley 193..199

Rhythmic Variability in European Vocal Music 193 RHYTHMIC VARIABILITY IN EUROPEAN VOCAL MUSIC DAVID TEMPERLEY to have higher variability in syllable length than French Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester (Grabe & Low, 2002). Several subsequent studies have further explored cross-cultural correlations between RHYTHMIC VARIABILITY IN THE VOCAL MUSIC OF music and language using nPVI. Huron and Ollen four European nations was examined, using the nPVI (2003) repeated Patel and Daniele’s procedure with measure (normalized pairwise variability index). It was a larger sample of instrumental melodies, and again predicted that English and German songs would show found English melodies to have higher nPVI than higher nPVI than French and Italian ones, mirroring French; they also found that German instrumental mel- the differences between these nations in speech rhythm, odies had relatively low nPVI, which is notable since the and in accord with previous studies of instrumental speech nPVI of German is relatively high. Daniele and music. Surprisingly, there was no evidence of this pat- Patel (2013) suggest that this may be due to the influ- tern, and some evidence of the opposite pattern: nPVI ence of Italian music on German composers (Italian is higher in French and Italian vocal music than in speech, like French, has fairly low nPVI); they show that English and German vocal music. This casts doubt on the nPVI of German instrumental music increases in the theory that the differences in instrumental rhythm the 19th century, as Italian influence wanes. This line between these nations are due to differences in speech of reasoning is pursued by Hansen, Sadakata, and Pearce rhythm. -

Cover No Spine

2006 VOL 44, NO. 4 Special Issue: The Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2006 The Journal of IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People Editors: Valerie Coghlan and Siobhán Parkinson Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Nina Christensen (Denmark), Penni Cotton (UK), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), Elwyn Jenkins (South Africa),Ariko Kawabata (Japan), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Maria Nikolajeva (Sweden), Jean Perrot (France), Kimberley Reynolds (UK), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Victor Watson (UK), Jochen Weber (Germany) Board of Bookbird, Inc.: Joan Glazer (USA), President; Ellis Vance (USA),Treasurer;Alida Cutts (USA), Secretary;Ann Lazim (UK); Elda Nogueira (Brazil) Cover image:The cover illustration is from Frau Meier, Die Amsel by Wolf Erlbruch, published by Peter Hammer Verlag,Wuppertal 1995 (see page 11) Production: Design and layout by Oldtown Design, Dublin ([email protected]) Proofread by Antoinette Walker Printed in Canada by Transcontinental Bookbird:A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People, Nonnenweg 12 Postfach, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland tel. +4161 272 29 17 fax: +4161 272 27 57 email: [email protected] <www.ibby.org>. Copyright © 2006 by Bookbird, Inc., an Indiana not-for-profit corporation. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Items from Focus IBBY may be reprinted freely to disseminate the work of IBBY. -

First Class Mail PAID

FOLK DANCE SCENE First Class Mail 4362 COOLIDGE AVE. U.S. POSTAGE LOS ANGELES, CA 90066 PAID Culver City, CA Permit No. 69 First Class Mail Dated Material ORDER FORM Please enter my subscription to FOLK DANCE SCENE for one year, beginning with the next published issue. Subscription rate: $15.00/year U.S.A., $20.00/year Canada or Mexico, $25.00/year other countries. Published monthly except for June/July and December/January issues. NAME _________________________________________ ADDRESS _________________________________________ PHONE (_____)_____–________ CITY _________________________________________ STATE __________________ E-MAIL _________________________________________ ZIP __________–________ Please mail subscription orders to the Subscription Office: 2010 Parnell Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90025 (Allow 6-8 weeks for subscription to go into effect if order is mailed after the 10th of the month.) Published by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South Volume 40, No. 1 February 2004 Folk Dance Scene Committee Club Directory Coordinators Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Calendar Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Beginner’s Classes (cont.) On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 Club Time Contact Location Contributing Editor Richard Duree [email protected] (714) 641-7450 CONEJO VALLEY FOLK Wed 7:30 (805) 497-1957 THOUSAND OAKS, Hillcrest Center, Contributing Editor Jatila van der Veen [email protected] (805) 964-5591 DANCERS Jill Lungren 403 W Hillcrest Dr Proofreading Editor Laurette Carlson [email protected] (310) 397-2450 ETHNIC EXPRESS INT'L Wed 6:30-7:15 (702) 732-4871 LAS VEGAS, Charleston Heights Art FOLK DANCERS except holidays Richard Killian Center, 800 S. -

Download the Transcript

CF VDC interview Melissa Obenauf/Živili 1 VDC Interview Transcript Živili/Melissa Pintar Obenauf 2.21.18 Total Time: 1:59:24 OhioDance Verne-Riffe Building 77 S. High St. Studio 3 Columbus, OH, 43215 Key: CF: Candace Feck MO: Melissa Obenauf JC: Jessica Cavender JD: Jane D’Angelo CF: We begin our long-awaited conversation! MO: Yes! CF: Let’s begin by talking about what inspired the founding of Živili, what led up to it, and how it began. MO: It’s an oft-told story, so I have no problem telling it again. When I graduated from college, and I graduated from OSU, where I had what was called “the elective sequence in dance” — so, basically I had two majors. When I graduated, my father, who is of Croatian descent — my grandparents are both from Croatia — said “Let’s go to Croatia! And let’s see where Ma and Pa are from.” And I said, “Sure — let’s do it!” So, I had grown up in a household where my mom was a professional violinist, so I was real involved with music, and had taken ballet from a very young age at Miami Conservatory1 —Miami is where I grew up. I was wanting to know more about my heritage, and had recently attended a dance company performance of a Yugoslavian dance company that had come to Miami, Florida. I was entranced with that and thought “Oooh! This is something I would like to know more about.” I had taken Folk Dance classes while I was in college with Maggie Patton,2 and loved folk dance. -

Fred L. Holmes a £

1948-CENTENNIAL EDITION-1948 M1 'A V, FRED L. HOLMES A £ OLD WORLD WISCONSIN AROUND EUROPE IN THE BADGER STATE Other Books by FRED L. HOLMES “Abraham Lincoln Traveled This Way” “George Washington Traveled This Way” “Alluring Wisconsin” “Badgei Saints and Sinners” “The Voice of Trappist Silence” •• OLD WORLD WISCONSIN Around Europe Jn the Badger State BY FRED L. HOLMES ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS, AND SKETCHES BY MAX FERNEKES “We are what we are because we stand on the shoulders of those who have preceded us. May we so live that those who follow us may stand on our shoulders.” —Anon. COPYRICHT, 1944 FRED L. HOLMES All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form whatever. First printing, May, 1944 Second printing, September, 1944 TO LOUIS W. BRIDGMAN A CLASSMATE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN ALWAYS MY FRIEND WHOSE MANY SERVICES HAVE BEEN MOST HELPFUL 6 0 ea>. "7? »«•*• "ASIANS r_/?REN xmicm CM (l I swedes finns / . •toil ■*|HIK«TDH IMAMS /4»amti*wa« Russians 0 ICELANDERS A. V • 'MMIIC MiaoiT M«M vj T. SWEDES (ltC**U *Kll y • cuifo* f imiuu #«lM«i. OTjfx^xxt BELGIANS Russians FRENCH if* ••out "t • »IU»*9 ^ . udi*>H OANES ' 1 «IIUI«IUI BOHEMIANS 1 HOLLANDERS j HOLLANDERS GERMANS MAOIIOM • CORNISH « -T MOnt( OANES ) YANKEELAND V _ SERBIANS / MAP Of WISCONSIN SHOWING RACIAL GROUPS AND PRINCIPAL LOCALITIES WHERE THEIR SETTLEMENTS ARE LOCATED PREFACE Through many questionings and wanderings in my native state, I have formed an appreciation, beyond ordi¬ nary measure, of the people who are Wisconsin. -

Dancers Under Duress: the Forgotten Resistance of Fireflies Laure Guilbert

Dancers Under Duress: The Forgotten Resistance of Fireflies Laure Guilbert “The dance of the fireflies, this moment of grace that resists the world of terror, is the most ephemeral, the most fragile thing that exists”. Georges Didi-Huberman, Survivance des lucioles (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2009). The “Unknown Dancer” She was sent to Drancy, deported from there to Auschwitz, and In the past years, I have undertaken many archival trips in Europe was gassed upon her arrival. and to Australia, searching for traces of the life of the German- speaking dancers and choreographers who fled the Third Reich Apart from these tragic cases, which have been detailed by other and occupied Europe. During that time, it became clear to me that researchers, I made a discovery that left me speechless while read- much work also needs to be undertaken so that we might gain a ing The Informed Heart: Autonomy in a Mass Age by the psychologist deeper understanding of the tragedy: those dancers, choreogra- Bruno Bettelheim from Vienna. In his book, Bettelheim analyzes the phers and dance producers who were trapped in ghettos and de- resources he managed to mobilize for surviving his own internment ported to extermination camps. In this paper I outline several fields from 1938-1939 in the Dachau concentration camp near Munich, of reflection that have enabled me to begin tracing the plight of and Buchenwald, near Weimar. Bettelheim at one point describes those artists caught up in Nazi totalitarianism. an event that takes place in Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. He sets the scene at the entrance to a gas chamber, and de- Certainly not all escaped the eye of the storm, not the least be- scribes a naked woman ordered to dance by an SS officer who had ing René Blum, director of the renowned Ballets Russes de Monte learned she was a dancer. -

9. Dancing and Politics in Croatia: the Salonsko Kolo As a Patriotic Response to the Waltz1 Ivana Katarinčić and Iva Niemčić

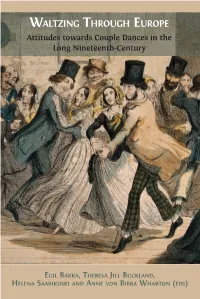

WALTZING THROUGH EUROPE B ALTZING HROUGH UROPE Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the AKKA W T E Long Nineteenth-Century Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the Long Nineteenth-Century EDITED BY EGIL BAKKA, THERESA JILL BUCKLAND, al. et HELENA SAARIKOSKI AND ANNE VON BIBRA WHARTON From ‘folk devils’ to ballroom dancers, this volume explores the changing recep� on of fashionable couple dances in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards. A refreshing interven� on in dance studies, this book brings together elements of historiography, cultural memory, folklore, and dance across compara� vely narrow but W markedly heterogeneous locali� es. Rooted in inves� ga� ons of o� en newly discovered primary sources, the essays aff ord many opportuni� es to compare sociocultural and ALTZING poli� cal reac� ons to the arrival and prac� ce of popular rota� ng couple dances, such as the Waltz and the Polka. Leading contributors provide a transna� onal and aff ec� ve lens onto strikingly diverse topics, ranging from the evolu� on of roman� c couple dances in Croa� a, and Strauss’s visits to Hamburg and Altona in the 1830s, to dance as a tool of T cultural preserva� on and expression in twen� eth-century Finland. HROUGH Waltzing Through Europe creates openings for fresh collabora� ons in dance historiography and cultural history across fi elds and genres. It is essen� al reading for researchers of dance in central and northern Europe, while also appealing to the general reader who wants to learn more about the vibrant histories of these familiar dance forms. E As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the UROPE publisher’s website. -

Published by the Folkdance Federation of California, South Volume 52, No

Published by the Folkdance Federation of California, South Volume 52, No. 4 May 2016 Folk Dance Scene Committee Coordinator Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Calendar Gerri Alexander [email protected] (818) 363-3761 On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 Dancers Speak Sandy Helperin [email protected] (310) 391-7382 Federation Corner Beverly Barr [email protected] (310) 202-6166 Proofreading Editor Jan Rayman [email protected] (818) 790-8523 Carl Pilsecker [email protected] (562) 865-0873 Design and Layout Editors Pat Cross, Don Krotser [email protected] (323) 255-3809 Business Managers Gerda Ben-Zeev [email protected] (310) 399-2321 Nancy Bott Circulation Sandy Helperin [email protected] (310) 391-7382 Subscriptions Gerda Ben-Zeev [email protected] (310) 399 2321 Advertising Steve Himel [email protected] Printing Coordinator Irwin Barr (310) 202-6166 Marketing Bob, Gerri Alexander [email protected] (818) 363-3761 Gerda Ben-Zeev Jill and Jay Michtom 19 Village Park Way Sandy Helperin 10824 Crebs Ave. Santa Monica, CA 90405 4362 Coolidge Ave. Northridge, CA 91326 Los Angeles, CA 90066 Folk Dance Scene Copyright 2016 by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc., of which this is the official publication. All rights reserved. Folk Dance Scene is published ten times per year on a monthly basis except for combined issues in June/July and December/January. First class postage is paid in Los Angeles, CA, ISSN 0430-8751. Folk Dance Scene is published to educate its readers concerning the folk dance, music, costumes, lore and culture of the peoples of the world. -

Nama Drmeš Medley

NAMA DRMEŠ MEDLEY Croatian PRONUNCIATION: NAH-mah DRR-mesh MED-lee TRANSLATION: Medley of three Croatian dances SOURCE: Dick Oakes learned these dances from Dick Crum. BACKGROUND: Drmeš iz Zdenčine, Kriči Kriči Tiček, and Kiša Pada (Posavski Drmeš) are the three "drmeši" (shaking dances) in this medley for which the transitions have been arranged by David Owens, the director of the NAMA Orchestra. Dick Crum, noted folk dance researcher, says that the drmeš, or shaking dance, is the most typical dance form in the northwestern part of Croatia. Drmeši are rarely danced today, except at weddings or other celebrations, and usually only by older dancers, dancing as couples or in small circles of three or four. Otherwise, the drmeš is usually only seen when performed by amateur dance groups who may select a tune and some movements culled from the older dancers for presentation to audiences as living museum pieces. Sometimes, groups from adjacent villages will select different movements and sequences for a particular melody common to both, giving rise to what puzzled American folk dancers sometimes think of as conflicting versions of the same dance. Drmeš iz Zdenčine (DRR-mesh ees SDEHN-chee-neh) comes from the village of Zdenčina, about half-way between Zagreb and Karlovac (near Jastrebarsko). It was collected in 1954 by Dick Crum. Kriči Kriči Tiček (KREE-chee KREE-chee TEE-chek) means "chirp chirp little bird" and originates in the Prigorije district, just north of Zagreb. This dance was also collected by Dick Crum in 1954. Kriči Kriči Tiček is one such dance that has undergone the natural preservative process. -

Christos Papakostas Gaida

LAGUNA FOLKDANCERS FESTIVAL 2013 SYLLABUS Christos Papakostas Gaida .......................................................................3 Gaida Poustseno or Amolyti Gaida................................................4 Hasapia......................................................................5 Karsilamas Aptalikos...........................................................6 Ormanli .....................................................................7 Pat(i)ma.....................................................................8 Pogonisios ...................................................................9 Poustseno...................................................................10 Sirtos & Balos ...............................................................11 Thiakos & Selfo..............................................................12 Željko Jergan Map of Hrvatska (Croatia)......................................................14 Gradiš4e Dances .............................................................15 Igre Bosanske................................................................19 Klin6ek.....................................................................22 Logovac ....................................................................25 Manfrina....................................................................28 Posavski Drmeši..............................................................31 Prosijala....................................................................33 Šoka6ko Kolo................................................................35