Psalm 10:1-11 Your Will Be Done in Most Hebrew Texts Psalms 9 and 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

![Psalms from Book III [Psalm 73, 75-77, 80, 84, 87 & 89]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8815/psalms-from-book-iii-psalm-73-75-77-80-84-87-89-648815.webp)

Psalms from Book III [Psalm 73, 75-77, 80, 84, 87 & 89]

READ The BIBLE Together Selected Psalms from Book III [Psalm 73, 75-77, 80, 84, 87 & 89] 15th February – 18th April 2015 SHALOM CHURCH, SINGAPORE (Upholding the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith) 1 Week 1 [15th – 21st February 2015] We read some selected psalms from Book I (Psalm 1-41) for our RTBT in May-June 2012 and some selected psalms from Book II (Psalm 42-72) for our RTBT in Mar-May 2013. For this current RTBT series, we shall be studying some selected psalms from Book III (Psalm 73-89). As we do so, let us first re-read the Introduction to the Book of Psalms: The Hebrew title of the Book of Psalms is ‘praise’. In other words, the Book of Psalms is the book of praise. Now, that’s an unusual title. Why do I say that? Survey the 150 individual psalms and you will see that there are more sad psalms than happy psalms, more psalms of laments than psalms of praise! That being so, why is the Book of Psalms called the book of praise? Survey the 150 individual psalms again and you will see this pattern emerging -- you will meet many sad psalms in the beginning, but as you move nearer to the end, the sad psalms decrease while the happy psalms increase! [Psalm 3 is a psalm of lament, so is Psalm 4, Psalm 6, Psalm 7, Psalm 10, Psalm 12, Psalm 13, to mention just the first few. Psalm 146 is a psalm of praise, and so also is Psalm 147, Psalm 148, Psalm 149 and Psalm 150!] The Book of Psalms moves from lamentations to praise, from the chords of sufferings to the choruses of praises. -

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms for the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms For the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel Today we start a new series in the Psalms. The Psalms provide a wonderful resource of Praying the Psalms inspiration and instruction for prayer and worship of God. Ezra collected the Psalms which were written over a millennium by a number of authors including David, Asaph, Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan and Moses. The Psalms are organized into 5 collections (1-41, 42-72, 73-89, 90-106, and 107-150). As we read the book of Psalms we see a variety of psalms including praise, lament, messianic, pilgrim, alphabetical, wisdom, and imprecatory prayers. The Psalms help us see the importance of God’s Word (Torah) and the hopeful expectation of God’s people for Messiah (Jesus). • Why is the “law of the Lord” such an important concept in Psalm 1 for bearing fruit as a follower of Jesus? • In John 15, Jesus says that apart from Him you can do nothing. Compare the message of Psalm 1 to Jesus’ words in John 15. Where are they similar? • Psalm 2 tells of kings who think they have influence and yet God laughs at them (v. 3). Why is it important that we seek our refuge in Jesus (2:12)? • Our heart for Bethel Church in this season is that we would saturate ourselves with God’s Word, specifically the book of Psalms. We’ve created a reading plan that allows you to read a Psalm a day or several Psalms per day as well as a Proverb. -

Especially Within the Colon Or Verse. in Addition, Phonetic Parallelism Seems to Play a Role Between Adjacent Verses, Specifi Cally Between Hk(Ydwhb and Hkdyb in Vv

PLEA FOR DELIVERANCE (11Q5 XVIII, ?–XIX, 18) 167 especially within the colon or verse. In addition, phonetic parallelism seems to play a role between adjacent verses, specifi cally between hk(ydwhb and hkdyb in vv. 4–5 and between hkm# and ytkmsn in vv. 13–14. Plea, like Apostrophe to Zion, makes relatively frequent use of biblical lan- guage and imagery. Th e second verse’s assertions that “worms” and “maggots” do not praise God resonate with many other biblical passages that speak in similar terms about “the dead” and “those who descend to the pit.” Th e verse (together with v. 3) alludes (through the vocabulary and syntax) more specifi cally, how- ever, to Isa 38:18–19. While in this biblical passage the living are contrasted with the dead in order to encourage God’s salvation, in the Plea the signifi cance of the contrast is subtler, something that can be inferred through a secondary allusion made in the same verse. Plea 2 also seems to allude to Job 25:6, where the word pair hmr and h(lwt occurs in parallelism, a rare occurrence in the Bible (see Isa 14:11). Th e Job passage is unlike that from Isaiah 38 in that the reference is not to the dead but rather to the abject state of humanity. Th e double allusion in Plea 2–3 (to Job 25 and Isa 38) complements the idea expressed in the following verses that humanity, when it lacks God’s mercy, is dejected and like the dead, unable to praise him. -

10 Hebrew Words for Praise 1. Yadah – to Revere, Give Thanks, Praise

10 Hebrew Words for Praise 1. Yadah – To revere, give thanks, praise Literally, this word means to extend or throw the hand. And it’s used elsewhere in the OT to refer to one casting stones or pulling back the bow. In an attempt to revere, in an attempt to give thanks, the human response to God is to extend your hands, to reach out in response to God. • Psalm 145:10 - “All your works shall give thanks to you, O Lord, and all Your saints shall bless You!” All creation reaches out in thanks and praise back toward the creator. • Psalm 139:14 - “I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” I praise you, I extend my hands to you for I am fearfully and wonderfully made by you. • Psalm 97:12 – “Rejoice in the Lord O you righteous, and give thanks to His holy name!” Yada means to give thanks, to revere, to praise by a physical throwing of the hands. 2. Barach – To bless, to praise as a blessing Literally, this word means to bow or to kneel. It’s what a person does when they come into the presence of a King. It’s an expression of humility. • Psalm 145:1 – “I will extol you, my God my King, and bless Your name forever and ever.” Verse 2- same thing- “Every day I will bless you (barach) and praise Your name forever.” • Psalm 95:6 - “Oh come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the Lord our Maker!” In this verse the psalmist uses 3 different words- “Come let us worship (literally shachah- bow down prostrate) and bow down (kara – crouch low), let us kneel (barach)- 3 different words that all mean some form of bowing down, crouching down, kneeling before… blessing in honor before. -

Predator, Prey and Protector

Predator, Prey, and Protector: Helping Victims Think and Act from Psalm 10 by David Powlison elen had been betrayed by her hus- insubstantial and insecure. All along, gen- band. He had played the part of the uine faith in God as refuge had intertwined Hdutiful, churchgoing husband, with Helen’s tendencies towards keeping father, and provider for many years. Their up appearances: “Put up with it, keep quiet, two children were in college. But unbe- pretend it’s not really happening, and every- knownst to Helen, he had maintained mis- thing’s OK.” Now she couldn’t keep silent. tresses in three cities. Helen had trusted him Now she couldn’t stand it any longer. Now with all the family finances, including a half- she couldn’t pretend. She was in trouble. million dollars she had inherited. He What should she say? How should she siphoned off all her money into his name. think? What should she do? Where does He spent much of it and ran up debts God fit amidst such devastation? Psalm 10 besides, financing a lifestyle of gambling, was uttered and written for those who have immorality, and partying. She’d been igno- rant of the adulteries and fraud, but she was not unaware of other evils. For many years their sexual relationship had been a private Psalm 10 is a message of honest agony to Helen. He routinely forced her to anguish and genuine refuge. commit acts she found repellent. In public his demeanor was usually pleasant; he was seemingly good-natured, quick-witted, worldly-wise, successful, confident, respon- been victimized by others. -

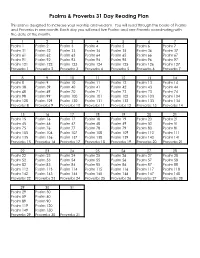

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

A Comprehensive Reading of Psalm 137

Simango, “Psalm 137,” OTE 31/1 (2018): 217-242 217 A Comprehensive Reading of Psalm 137 DANIEL SIMANGO (NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY) ABSTRACT The purpose of this article is to carry out a thorough exegetical study of Ps 137 in order to grasp its content, context and theological implications. The basic hypothesis of this study is that Ps 137 can be best understood when the text is thoroughly analysed. Therefore, in this article, Ps 137 will be read in its total context (i.e. historical setting, life-setting and canonical setting) and its literary genre. The article concludes by discussing the imprecatory implications and message of Ps 137 to the followers of YHWH. KEYWORDS: Psalm 137; Exegetical Study; Imprecatory Psalms; Imprecation. A INTRODUCTION Psalm 137 is one of the best known imprecatory psalms that focus on the traumatic experience of exile in Babylon. The psalm reveals the sufferings and sentiments of the people who probably experienced at first hand the grievous days of the conquest and destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE and who shared the burden of the Babylonian captivity after their return to their homeland. At the sight of the ruined city and the temple, the psalmist vents with passionate intensity his deep love for Zion as he recalls the distress of alienation from their sanctuary. Therefore, this psalm touches the raw nerve of Israel’s faith. The poem commences with the melancholy recollection of the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem which caused the Israelite captives to mourn and stop playing their musical instruments. The Babylonian masters asked the captives to join them in the mockery of YHWH. -

Metrical Psalter Book 1 V 1-0-3

The Psalms in metre Book 1 Psalms 1-41 Book 1 ; Page 1 © Dru Brooke-Taylor 2015, the author’s moral rights have been asserted. For further information both on copyright and how to use this material see https://psalmsandpsimilar.wordpress.com v 1.0.3 : 15 vi 2015 Book 1 ; Page 2 Table of Contents Psalm 1 (SHa) CM 5 Psalm 2 (SHa)CM 6 Psalm 3 (SHa) CM 8 Psalm 4 (SHa)CM 10 Psalm 5 (TBa) CM 11 Psalm 6 (TBa) CM 13 Psalm 7 (SHa) CM 14 Psalm 8 (SHa) CM 16 Psalm 8-B (DBT) 13,13,13,13,13,13 18 Psalm 9 (SHa) CM 20 Psalm 10 (SHa) CM 22 Psalm 11 (DBT) CM 24 Psalm 12 - (SHa) CM 25 Psalm 13 (SHa) CM 26 Psalm 14 - (SHa) CM 27 Psalm 14-B - Another version (TB unaltered) LM 28 Psalm 15 - (SHa) CM 30 Psalm 16 - (SHa) CM 31 Psalm 17 - (SHa) CM 33 Part 2 34 Psalm 18 - (SHa) CM 35 Psalm 19 (SHa) CM 40 Psalm 20 (SHa) CM 42 Psalm 21 (SHa) DCM 43 Psalm 22 (SHa) CM 45 Part 2 46 Part 3 46 Psalm 23 (R) CM 48 Psalm 23 - B (SHa) CM 48 Psalm 23 - C A version by Sir H. W. Baker 8787 49 Psalm 23 - D - a version by Addison 88 88 88 50 Psalm 24 (TBa) DCM 52 Psalm 24 - B Dr Watts version to Kingsbridge in LM 54 Part 2 55 Psalm 25 (SHa) DSM 56 Part 2 57 Psalm 26 (SHa) CM 59 Psalm 27 (SHa) CM 60 Psalm 28 (SHa) CM 62 Psalm 29 (SHa) CM 63 Psalm 30 (DBT) DCM 65 Psalm 31 (SHa) CM 67 Psalm 32 (SHa) CM 70 Psalm 33 (TB) CM 72 Part 2 73 Psalm 34 (TB) CM 74 Part 2 75 Psalm 35 (TBa) CM 76 Book 1 ; Page 3 Part 2 77 Part 3 77 Psalm 36 (SHa) CM 79 Psalm 37 (TBa) 888 888 81 Part 2 82 Part 3 83 Part 3 84 Psalm 38 (SHa) CM 86 Part 2 87 Psalm 39 (SHa) CM 88 Psalm 40 (SHa) CM 90 Psalm 40 - B (TBa) LM 92 Psalm 41 (SHa) DCM 94 Book 1 ; Page 4 Psalm 1 (SHa) CM Playford has a good tune in three line harmony, which floats between Emi and G Maj, which is below as ‘Old First’ with the addition of an alto line and some ornamentation. -

Declare How Much God Has Done for You

Notes: Sermon Text Suggested Daily Scripture Reading June 24 - June 30 Subject Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday OT II Kings 4:18-5:27 II Kings 6:1-7:20 II Kings 8:1-9:13 II Kings 9:14-10:31 NT Acts 15:1-35 Acts 15:36-16:15 Acts 16:16-40 Acts 17:1-34 PSA Psalm 141:1-10 Psalm 142:1-7 Psalm 143:1-12 Psalm 144:1-15 PROV Proverbs 17:23 Proverbs 17:24-25 Proverbs 17:26 Proverbs 17:27-28 Thursday Friday Saturday II Kings 10:32-12:21 II Kings 13:1-14:29 II Kings 15:1-16:20 Acts 18:1-22 Acts 18:23-19:12 Acts 19:13-41 Psalm 145:1-21 Psalm 146:1-10 Psalm 147:1-20 Proverbs 18:1 Proverbs 18:2-3 Proverbs 18:4-5 July 1 - 7 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Declare how much OT II Kings 17:1-18:12 II Kings 18:13-19:37 II Kings 20:1-22:2 II Kings 22:3-23:30 NT Acts 20:1-38 Acts 21:1-7 Acts 21:18-36 Acts 21:37-22:16 PSA Psalm 148:1-14 Psalm 149:1-9 Psalm 150:1-6 Psalm 1:1-6 God has done for you . PROV Proverbs 18:6-7 Proverbs 18:8 Proverbs 18:9-10 Proverbs 18:11-12 Thursday Friday Saturday II Kings 23:31-25:30 1 Chronicles 1:1-2:17 1 Chronicles 2:18-4:4 Luke 8:39 Acts 22:17-23:10 Acts 23:11-35 Acts 24:1-27 Psalm 2:1-12 Psalm 3:1-8 Psalm 4:1-8 Proverbs 18:13 Proverbs 18:14-15 Proverbs 18:16-18 Spiritual “To Do List” July 8 - 15 (things God has shown me today) Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday OT 1 Chronicles 4:5-5:17 1 Chronicles 5:18-6:81 1 Chronicles 7:1-8:40 1 Chronicles 9:1-10:14 NT Acts 25:1-27 Acts 26:1-32 Acts 27:1-20 Acts 27:21-44 PSA Psalm 5:1-12 Psalm 6:1-10 Psalm 7:1-17 Psalm 8:1-9 PROV Proverbs 18:19 Proverbs 18:20-21 Proverbs 18:22 Proverbs 18:23-24 Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 1 Chronicles 11:1-12:18 1 Chronicles 12:19-14:17 1 Chronicles 15:1-16:36 1 Chronicles 16:37-18:17 Acts 28:1-31 Romans 1:1-17 Romans 1:18-32 Romans 2:1-24 Psalm 9:1-12 Psalm 9:13-20 Psalm 10:1-15 Psalm 10:16-18 Proverbs 19:1-3 Proverbs 19:4-5 Proverbs 19:6-7 Proverbs 19:8-9 PHOTO: KIM RISON 5-15-2018 Used by permission Notes: Pilgrim Holiness Church, Rt. -

The University of Chicago Literary Genres in Poetic

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LITERARY GENRES IN POETIC TEXTS FROM THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY WILLIAM DOUGLAS PICKUT CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 © Copyright 2017 William Douglas Pickut All rights reserved For Mom and for Matt –A small cloud of witnesses. For Grace and Jake and Mary – Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths… “Many persons have believed that this book's miraculous stupidities were studied and disingenuous; but no one can read the volume carefully through and keep that opinion. It was written in serious good faith and deep earnestness, by an honest and upright idiot who believed he knew something of the language, and could impart his knowledge to others.” Mark Twain Introduction to the US edition of English as She is Spoke by Jose da Fonseca and Pedro Carolinho 1855 Table of Contents Tables…………………………………………………………………………………….vii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………xii Foreword………………………………………………………………………………....xiii 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 2. Method……………………………………………………………………………17 2.1 The Clause as the basic unit of discourse…………………………………….17 2.2 Problems with the line………………………………………………………..18 2.3 Advantages of the clause……………………………………………………...20 2.4 Layered structure of the clause (LSC)………………………………………..23 2.5 What the LSC does……………………………………………………………32 2.6 Semantic content………………………………………………………………34 2.7 Application of Functional Grammar and semantic analysis…………………..36 2.7.1 Terseness (and un-terseness)………………………………………….36 2.7.2 Parallelism (Repetition)……………………………………………….40 2.8 Examples………………………………………………………………………46 2.8.1 Terse with no repetition……………………………………………….46 2.8.2 Terse with repetition…………………………………………………..47 2.8.3 Terse by ellipsis……………………………………………………….49 2.8.4 Un-terse………………………………………………………………..50 3. -

Selah Moments Sacred Pauses Your Soul For

Selah Moments sacred pauses your soul for A JOYFUL LIFE STUDY AIMEE WALKER by All Text in this study guide is the property of AimEe Walker and THE JOYFUL LIFE COMPANY. You are welcome to share excerpts from the text, provided that full and clear credit is given to AimEe and THE JOYFUL LIFE COMPANY. © copyright 2019, the joyful life company edited by tiffany edmonds cover image BY Carolyn watson COLORING PAGE ART BY TASHA WIGINTON All scripture references throughout are English Standard Version (ESV) unless noted. www.joyfullifemagazine.com Selah Moments sacred pauses your soul for table of contents INTRODUCTION DAY 1 | An Evaluating Pause 8 DAY 2 | A Spacious Pause 13 DAY 3 | A Searching Pause 19 DAY 4 | A Solemn Pause 25 DAY 5 | A Victorious Pause 33 WEEKEND REFLECTION A Thankful Pause 38 DAY 6 | A Consecrating Pause 45 DAY 7 | A Blessed Pause 51 DAY 8 | A Meaningful Pause 57 DAY 9 | A Loving Pause 63 DAY 10 | A Still Pause 68 WEEKEND REFLECTION An Honoring Pause 74 table of contents You, Yahweh, have become my ; You take me and shield surround me with Yourself... Ps. 3:3 ESV Introduction Selah. It’s a beautiful, if not somewhat mysterious, word. A word that beckons and invites us to slow down; to linger and pause in God’s presence; to pay attention not only to our own stories, but to Him. Throughout this study, you are invited to record the names and attributes of God spoken of in each Psalm in a list you’ll find at the back of this devotional.