Freud on Time and Timelessness: the Ancient Greek Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 Zeus + Plouto 18. Zeus + Electra Teucros Tantalos Oinomaos

Pe ops + Nippodameir da!shte6 Asa.acos Ganymedes Anchhes + Aphrodite8i']? Cl a Cytios !:r€9!: Elethyia Ares 0,2 Hephaitlos m laoetos +Asiar A".' Zeus + l'1a a Eecrn 3 other daughters 308 ovrD OYID 309 50 I musr endlcssly feel rhe los ofan absenr husband. Or of Euryrmchus and -Arrinous' ever srabbins hands? The towes ofTroy havc been razed; for me alone, tliey still remair, O. all lhe re$ whom you in your absence are alLowing to grow fet rhoush a vlcrorious scrder plows dle l.nd willt a caprured ox. on fie trcdures won at rhe cos ofyour blood? Where Troy once stood rherei; onLy a fietd of grah. The canh flourishes, Your final huniliation? Add to your lose the beggr Irus and fenilized by Phrygim blood. arvaiting the harvesring sickle. Melanthius, who drives you. flock ro feed rhe suiros'bellies. Cu*ed plowshr* str;ke the half-buried bones ofnen, \tre fe only three in number, allunsuircd fo. war-a powerles wife, and rhe ruins orfallen houses lie hidden arrong rhe weeds. your old fatheq Laenes, and Telemachus, just a boy, md him r-c,. w .pr :iC Though victorious, you arc still sone, and I have no way of krowhg I rJrnor lo.r ,e,er .ly ro " hryou. rlo- - h. r o why the delay. or where your unfeeling hearr is hidirg. ro.ait ro fyto, "grir r rhe, olJt h,orh,.. Every srilor who turns a foreign ship to these shores leaves I pray rhn the gods preserye rhe ba ral order ofrhe Fares, rhar only aftet answering numetous questions aboutyou, he willclose borh my eyes and yous on our fina.lda1s. -

201 8 201 Youth Creative Daycamps & Workshops Daycamps Youth Creative

SUMMER201 8 WRITE | SUMMERWRITE 2018 CLASSESWORKSHOPS | & TO REGISTER,TO 473-2590 X107 CALL | WAB.ORG 1 SPRING & SUMMER YOUTH CREATIVE DAYCAMPS & WORKSHOPS Things to Know Group Size and Instructor Ratio: Workshops are limited to a total addition, daily playground break-time or other outdoor activities are scheduled for enrollment of 12 students with the exception of a few specific classes. Most workshops each group. Some classes also take place at our rural facility, Gell: A Finger Lakes are led by one adult teaching artist and one high school or college apprentice. Creative Retreat, located on 24 acres in scenic South Bristol. What to Bring: Unless otherwise noted in the description, all you need is Map & Directions: a pen and paper, water bottle, and lunch if you’re staying all day. Please leave cell Writers & Books is located at phones and other electronic devices at home or turned off completely and tucked in a 740 University Avenue between backpack or bag. Merriman Street and Atlantic Avenue in the Neighborhood of Food: Snacks are provided for breaks, though please bring a water bottle. Full day the Arts. participants bring their own lunches. Please make note of any allergies or dietary restrictions on the registration form and we will do our best to accommodate. Where to Park: There is parking in our lot, which can be entered from University Avenue Choose Full Days or Half Days: Workshops offered are either half Emily DeLucia photo by days or full days. A morning workshop may be combined with an afternoon workshop or Atlantic Avenue. Parking is for a full day of programming. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the Birth of Dionysus

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the birth of Dionysus Caesar van Everdingen. Rape of Europa. 1650 Zeus = Io Memphis = Epaphus Poseidon = Libya Lysianassa Belus Agenor = Telephassa In the Danaid, we followed the descendants of Belus. The Thebaid follows the descendants of Agenor Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Agenor migrated to the Levant and founded Sidon • But see Josephus, Jewish Antiquities i.130 - 139 • “… for Syria borders on Egypt, and the Phoenicians, to whom Sidon belongs, dwell in Syria.” (Hdt. ii.116.6) The Levant Levant • Jericho (9000 BC) • Damascus (8000) • Biblos (7000) • Sidon (4000) Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Jericho Levant • Canaanites: • Aramaeans • Language, not race. • Moved to the Levant ca. 1400-1200 BC • Phoenician = • purple dye people Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Zeus appeared to Europa as a bull and carried her to Crete. • Agenor sent his sons in search of Europa • Don’t come home without her! • The Rape of Europa • Maren de Vos • 1590 Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (Spain) Image courtesy of wikimedia • Rape of Europa • Caesar van Everdingen • 1650 • Image courtesy of wikimedia • Europe Group • Albert Memorial • London, 1872. • A memorial for Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Crete Europa = Zeus Minos Sarpedon Rhadamanthus • Asterius, king of Crete, married Europa • Minos became king of Crete • Sarpedon king of Lycia • Rhadamanthus king of Boeotia The Brothers of Europa • Phoenix • Remained in Phoenicia • Cylix • Founded -

Gender, Sexuality and the Theory of Seduction

J O H N F L E T C H E R .................................................................................................................................................. Gender, Sexuality and the Theory of Seduction o readdress the conjunction of psychoanalysis and gender one must first pose the question as to whether psychoanalysis is, or has, or can be expected to Tprovide, a theory of gender as such. For it was in something like that hope that certain forms of feminism and radical social theory turned to psycho- analysis in the 1970s. Is gender, however, a properly psychoanalytic or metapsychological category? Or, rather, does not psychoanalysis borrow the categories of masculine and feminine from the life-world of social practice and its ideologies, even at times from the theories of sociology, just as it purloins certain theoretical concepts and categories of biology and physi- ology with their accounts of the body and its functions of self-preservation? However, psychoanalysis borrows and purloins understandings of both gender and the body in order to give an account of something else: something that indeed bears on how we live subjectively our gendered and embodied lives, although this cannot make of psychoanalysis a substitute for an explanation of the social production of gender categories and gendered positions within the various fields of social practice, anymore than psycho- analysis can be a substitute for a science of the body and its developmental and self-preservative functioning. This something else is the unconscious and sexuality, the object of psychoanalysis. I want provisionally to hold apart, to separate at least analytically gender, sexuality and sexual difference, in order to interrupt the too easy assimilation ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and Was Thought of As the Personification of Cyclic Law, the Causal Power of Expansion, and the Angel of Miracles

Ζεύς The Angel of Cycles and Solutions will help us get back on track. In the old schools this angel was known as Jupiter (Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and was thought of as the personification of cyclic law, the Causal Power of expansion, and the angel of miracles. Price, John Randolph (2010-11-24). Angels Within Us: A Spiritual Guide to the Twenty-Two Angels That Govern Our Everyday Lives (p. 151). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Zeus 1 Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice [1] The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680 Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak Consort Hera and various others Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter Children Aeacus, Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Dardanus, Dionysus, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces [2] Roman equivalent Jupiter Zeus (Ancient Greek: Ζεύς, Zeús; Modern Greek: Δίας, Días; English pronunciation /ˈzjuːs/[3] or /ˈzuːs/) is the "Father of Gods and men" (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε, patḕr andrōn te theōn te)[4] who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.[5] He is known for his erotic escapades. -

Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus' Europia

Gaia Revue interdisciplinaire sur la Grèce archaïque 22-23 | 2020 Varia The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia La généalogie de Dionysos: Bacchylide 19 et l’Europia d’Eumélos Marios Skempis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/gaia/512 ISSN: 2275-4776 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version ISBN: 978-2-37747-199-7 ISSN: 1287-3349 Electronic reference Marios Skempis, « The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia », Gaia [Online], 22-23 | 2020, Online since 30 June 2020, connection on 17 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/gaia/512 This text was automatically generated on 17 July 2020. Gaia. Revue interdisciplinaire sur la Grèce archaïque The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia 1 The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia La généalogie de Dionysos: Bacchylide 19 et l’Europia d’Eumélos Marios Skempis 1 Bacchylides’ relation to the Epic Cycle is an issue under-appreciated in the study of classical scholarship, the more so since modern Standardwerke such as Martin West’s The Epic Cycle and Marco Fantuzzi and Christos Tsagalis’ The Greek Epic Cycle and Its Reception: A Companion are unwilling to engage in discussions about the Cycle’s impact on this poet.1 A look at the surviving Dithyrambs in particular shows that Bacchylides appropriates the Epic Cycle more thoroughly than one expects: Bacchylides 15 reworks the Cypria’s Request for Helen’s Return (arg. 10 W); Bacchylides 16 alludes to Creophylus’ Sack of Oechalia; Bacchylides 17 and 18 are instantiations of mythical episodes plausibly excerpted from an archaic Theseid; Bacchylides 19 opens and ends its mythical section with a circular mannerism that echoes the Thebaid’s incipit (fr. -

Oedipal Guilt, Punishment and Criminal Behaviour

! OEDIPAL GUILT, PUNISHMENT AND CRIMINAL BEHAVIOUR ! By Brendan Dolan ! ! The Thesis is submitted to the Higher Education and Training Awards Council (HETAC) for the award of Higher Diploma in Counselling and Psychotherapy form Dublin Business School, School Of Arts. ! May 2014 ! Supervisor - Cathal O’Keeffe ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "1 Contents ! ! Abstract Page 3 Introduction Page 4 Chapter 1. Freud - Criminals from a sense of Guilt Page 6 Chapter 2. Lacan - The No/Name of the Father Page 8 Chapter 3. Punishment, Guilt and the Severe Superego Page 11 Chapter 4. Discussion Page 15 Conclusion Page 17 Bibliography Page 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "2 ! Abstract The successful negotiation of the Oedipus complex is vital for our psychical development as it provides us with the means to form relationships and integrate into society. Resolution of the Oedi- pus complex requires the intervention of the father (Freud) or a symbolic representation of the func- tion of the father (Lacan). Unresolved Oedipal issues lead to unconscious guilt which over time can become unbearable causing the individual to seek to externalise the guilt through the commission of crime in order to receive the punishment their guilt demands. Freud calls these individuals Crimi- nals from a sense of guilt. This paper looks at the theory of Freud and Lacan around criminal be- haviour and the Oedipus complex. It also shows that the desire of the individual for punishment to expiate unconscious guilt, the desire of society to punish in order to expiate inherited unconscious guilt and the presence of a severe Superego all collude to entice the individual to commit crime.The application of psychoanalytical theory to the legal and penal system shows that rather than acting as a deterrent they may in fact incite the commission of crime. -

Johnny Foreigner

REVIEWS Johnny foreigner Simon Glendinning, ed., The Edinburgh Encyclopedia of Continental Philosophy, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1999. xiv + 685 pp., £80.00 hb., 0 7486 0783 8. If the Encyclopédie project of Diderot et al. is quotes Ryle (of whom one might have expected better) remembered today, it is not because it is much con- addressing an audience in France at a supposedly sulted, but for the tremendous Enlightenment optimism bridge-building conference in 1958, explaining how that made its conception (if not its completion) pos- analytic philosophers have avoided the puff and pre- sible. In historical terms, it is the idea of the Ency- tension of the continent. In contrast to the likes of clopédie that is most important, not what is contained Husserl, says Ryle, within the volumes themselves. The idea of the or British thinkers have showed no inclination to even an Encyclopedia is, however, beginning to look assimilate philosophical to scientific enquiry.… increasingly like a Borgesian fantasy. Most contem- I guess that our thinkers have been immunized porary encyclopedias are decidedly (purposefully) against the idea of philosophy as the Mistress of limited in scope; to be successful they must function, Science by the fact that their daily lives in Cam- bridge and Oxford Colleges have kept them in con- immediately and with some enduring relevance, as tact with real scientists. Claims to Führership vanish sources of reference and information to be used in when postprandial joking begins. Husserl wrote as if piecemeal fashion. To this extent, The Edinburgh he had never met a scientist – or a joke. -

View / Open Hayes Oregon 0171A 12498.Pdf

TO WRITE THE BODY: LOST TIME AND THE WORK OF MELANCHOLY by SHANNON HAYES A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Philosophy and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2019 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Shannon Hayes Title: To Write the Body: Lost Time and the Work of Melancholy This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Philosophy by: Alejandro Vallega Chairperson Rocío Zambrana Core Member Ted Toadvine Core Member Jeffrey Librett Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2019. ii © 2019 Shannon Hayes This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Shannon Hayes Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy June 2019 Title: To Write the Body: Lost Time and the Work of Melancholy In this dissertation I develop a philosophical account of melancholy as a productive, creative, and politically significant affect. Despite the longstanding association of melancholy with the creativity and productivity of poets, artists, and philosophers, melancholy is judged to be a nonpolitical mood associated with stagnancy, paralysis, and a willful alienation. If Marxist critical theory still holds true today and it remains the case we are already dismembered and distanced in our worldly relations, then melancholy is a mood that unmasks our present situation. In the fatigue and weariness of the melancholic body, there is an insight into the decay and fragmentation that characterizes social existence. -

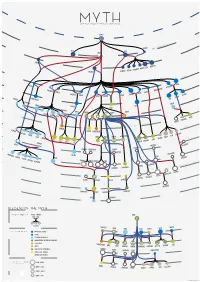

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

Totem, Taboo and the Concept of Law: Myth in Hart and Freud Jeanne L

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 1 | Issue 1 2009 Totem, Taboo and the Concept of Law: Myth in Hart and Freud Jeanne L. Schroeder Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Jeanne L. Schroeder, Totem, Taboo and the Concept of Law: Myth in Hart and Freud, 1 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 139 (2009). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Totem, Taboo and the Concept of Law: Myth in Hart and Freud Jeanne L. Schroeder* A startling aspect of H.L.A. Hart’s The Concept of Law1 is just how profoundly it rests on imaginary anthropology. Hart suggests that the development of “secondary” rules of change, recognition, and adjudication to supplement “primary,” or substantive, rules of law is the process by which primitive societies evolve into modern ones. In fact, like the writers of Genesis, Hart actually modulates between two unconnected creation stories. According to one, the rule of law is created after the death of a conqueror, Rex I, to insure the succession of his idiot son, Rex II. In a second story, primitive society loses its direct relationship with primary laws and develops the secondary rules.