Conserving Atlantic Bluefin Tuna with Spawning Sanctuaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FISH LIST WISH LIST: a Case for Updating the Canadian Government’S Guidance for Common Names on Seafood

FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood Authors: Christina Callegari, Scott Wallace, Sarah Foster and Liane Arness ISBN: 978-1-988424-60-6 © SeaChoice November 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY . 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 Findings . 5 Recommendations . 6 INTRODUCTION . 7 APPROACH . 8 Identification of Canadian-caught species . 9 Data processing . 9 REPORT STRUCTURE . 10 SECTION A: COMMON AND OVERLAPPING NAMES . 10 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 10 Results . 11 Snapper/rockfish/Pacific snapper/rosefish/redfish . 12 Sole/flounder . 14 Shrimp/prawn . 15 Shark/dogfish . 15 Why it matters . 15 Recommendations . 16 SECTION B: CANADIAN-CAUGHT SPECIES OF HIGHEST CONCERN . 17 Introduction . 17 Methodology . 18 Results . 20 Commonly mislabelled species . 20 Species with sustainability concerns . 21 Species linked to human health concerns . 23 Species listed under the U .S . Seafood Import Monitoring Program . 25 Combined impact assessment . 26 Why it matters . 28 Recommendations . 28 SECTION C: MISSING SPECIES, MISSING ENGLISH AND FRENCH COMMON NAMES AND GENUS-LEVEL ENTRIES . 31 Introduction . 31 Missing species and outdated scientific names . 31 Scientific names without English or French CFIA common names . 32 Genus-level entries . 33 Why it matters . 34 Recommendations . 34 CONCLUSION . 35 REFERENCES . 36 APPENDIX . 39 Appendix A . 39 Appendix B . 39 FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood 2 GLOSSARY The terms below are defined to aid in comprehension of this report. Common name — Although species are given a standard Scientific name — The taxonomic (Latin) name for a species. common name that is readily used by the scientific In nomenclature, every scientific name consists of two parts, community, industry has adopted other widely used names the genus and the specific epithet, which is used to identify for species sold in the marketplace. -

Do Some Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Skip Spawning?

SCRS/2006/088 Col. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 60(4): 1141-1153 (2007) DO SOME ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA SKIP SPAWNING? David H. Secor1 SUMMARY During the spawning season for Atlantic bluefin tuna, some adults occur outside known spawning centers, suggesting either unknown spawning regions, or fundamental errors in our current understanding of bluefin tuna reproductive schedules. Based upon recent scientific perspectives, skipped spawning (delayed maturation and non-annual spawning) is possibly prevalent in moderately long-lived marine species like bluefin tuna. In principle, skipped spawning represents a trade-off between current and future reproduction. By foregoing reproduction, an individual can incur survival and growth benefits that accrue in deferred reproduction. Across a range of species, skipped reproduction was positively correlated with longevity, but for non-sturgeon species, adults spawned at intervals at least once every two years. A range of types of skipped spawning (constant, younger, older, event skipping; and delays in first maturation) was modeled for the western Atlantic bluefin tuna population to test for their effects on the egg-production-per-recruit biological reference point (stipulated at 20% and 40%). With the exception of extreme delays in maturation, skipped spawning had relatively small effect in depressing fishing mortality (F) threshold values. This was particularly true in comparison to scenarios of a juvenile fishery (ages 4-7), which substantially depressed threshold F values. Indeed, recent F estimates for 1990-2002 western Atlantic bluefin tuna stock assessments were in excess of threshold F values when juvenile size classes were exploited. If western bluefin tuna are currently maturing at an older age than is currently assessed (i.e., 10 v. -

Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus Albacares) and Albacore (Thunnus Alalunga) (Perciformes: Scombrinae) in the Atlantic, Indian and Eastern Pacific Oceans

SCRS/2009/024 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 65(2): 717-724 (2010) LENGTH-WEIGHT RELATIONSHIPS FOR BIGEYE TUNA (THUNNUS OBESUS), YELLOWFIN TUNA (THUNNUS ALBACARES) AND ALBACORE (THUNNUS ALALUNGA) (PERCIFORMES: SCOMBRINAE) IN THE ATLANTIC, INDIAN AND EASTERN PACIFIC OCEANS Guoping Zhu, Liuxiong Xu*,Yingqi Zhou, Liming Song and Xiaojie Dai SUMMARY The length-weight relationships (LWRs) for bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and albacore (Thunnus alalunga) collected in the Atlantic, Indian and Eastern Pacific Oceans are presented. Significant differences can be found from the fork length distributions and the LWRs of the above 3 tuna species and the relations of dressed weight and round weight of bigeye and yellowfin tunas collected from the Atlantic, Indian and Eastern Pacific Oceans. The growth type of bigeye and yellowfin tuna in the Eastern Pacific Ocean showed positive allometries, whereas bigeye and yellowfin tuna from the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and albacore from the Atlantic, Indian and Eastern Pacific Oceans indicated negative allometries. RÉSUMÉ Le présent document décrit les relations longueur-poids (LWR) du thon obèse (Thunnus obesus), de l’albacore (Thunnus albacares) et du germon (Thunnus alalunga) prélevés dans les océans Atlantique, Indien et Pacifique de l’Est. Des différences considérables peuvent être trouvées dans les distributions longueur-fourche et les relations longueur-poids des trois espèces thonières susmentionnées et dans les relations du poids manipulé et du poids vif du thon obèse et de l’albacore collectés dans les océans Atlantique, Indien et Pacifique Est. Le type de croissance du thon obèse et de l’albacore dans l’océan Pacifique Est a révélé des allométries positives, tandis que le thon obèse et l’albacore des océans Atlantique et Indien et le germon des océans Atlantique, Indien et Pacifique Est ont fait apparaître des allométries négatives. -

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus Thynnus) Population Dynamics

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8522–8527 nations of the International Commission for the Conservation Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) currently manage ABFT fisheries thynnus) Population Dynamics assuming two units (a western stock spawning in the Gulf of Mexico, and an eastern stock which spawns in the Delineated by Organochlorine Mediterranean Sea) ostensibly separated by the 45° W meridian with little intermixing between stocks. However, Tracers tagging studies indicate that bluefin tuna undergo extensive and complex migrations, including trans-Atlantic migrations, ,† and that stock mixing could be as high as 30% (2-4). Extensive REBECCA M. DICKHUT,* - ASHOK D. DESHPANDE,‡ mixing of eastern and western stocks (35 57% bluefin tuna ALESSANDRA CINCINELLI,§ of eastern origin) within the U.S. Mid Atlantic Bight was also 18 MICHELE A. COCHRAN,† reported recently based on otolith δ O values (5). The SIMONETTA CORSOLINI,| uncertainty of stock structures due to mixing makes it difficult RICHARD W. BRILL,† DAVID H. SECOR,⊥ for fisheries managers to assess the effectiveness of rebuilding AND JOHN E. GRAVES† efforts for the dwindling western Atlantic spawning stock of Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, bluefin tuna. Understanding ABFT spatial distributions and Virginia 23062, National Marine Fisheries Service, dynamics are vital for robust population assessments and Highlands, New Jersey 07732, Department of Chemistry, the design of effective management strategies, and there is University of Florence, 50019 -

NOAA's Description of the U.S Commercial Fisheries Including The

6.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE PELAGIC LONGLINE FISHERY FOR ATLANTIC HMS The HMS FMP provides a thorough description of the U.S. fisheries for Atlantic HMS, including sectors of the pelagic longline fishery. Below is specific information regarding the catch of pelagic longline fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico and off the Southeast coast of the United States. For more detailed information on the fishery, please refer to the HMS FMP. 6.1 Pelagic Longline Gear The U.S. pelagic longline fishery for Atlantic HMS primarily targets swordfish, yellowfin tuna, or bigeye tuna in various areas and seasons. Secondary target species include dolphin, albacore tuna, pelagic sharks including mako, thresher, and porbeagle sharks, as well as several species of large coastal sharks. Although this gear can be modified (i.e., depth of set, hook type, etc.) to target either swordfish, tunas, or sharks, like other hook and line fisheries, it is a multispecies fishery. These fisheries are opportunistic, switching gear style and making subtle changes to the fishing configuration to target the best available economic opportunity of each individual trip. Longline gear sometimes attracts and hooks non-target finfish with no commercial value, as well as species that cannot be retained by commercial fishermen, such as billfish. Pelagic longline gear is composed of several parts. See Figure 6.1. Figure 6.1. Typical U.S. pelagic longline gear. Source: Arocha, 1997. When targeting swordfish, the lines generally are deployed at sunset and hauled in at sunrise to take advantage of the nocturnal near-surface feeding habits of swordfish. In general, longlines targeting tunas are set in the morning, deeper in the water column, and hauled in the evening. -

A Preliminary Study on the Stomach Content of Southern Bluefin Tuna Thunnus Maccoyii Caught by Taiwanese Longliner in the Central Indian Ocean

CCSBT-ESC/0509/35 A preliminary study on the stomach content of southern bluefin tuna Thunnus maccoyii caught by Taiwanese longliner in the central Indian Ocean Kwang-Ming Liu1, Wei-Ke Chen2, Shoou-Jeng Joung2, and Sui-Kai Chang3 1. Institute of Marine Resource Management, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, Taiwan. 2. Department of Environmental Biology and Fisheries Science, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, Taiwan. 3. Fisheries Agency, Council of Agriculture, Taipei, Taiwan. Abstract The stomach contents of 63 southern bluefin tuna captured by Taiwanese longliners in central Indian Ocean in August 2004 were examined. The size of tunas ranged from 84-187 cm FL (12-115 kg GG). The length and weight frequency distributions indicated that most specimens were in the range of 100-130 cm FL with a body weight between 10 and 30 kg for both sexes. The sexes- combined relationship between dressed weight and fork length can be described by W = 6.975× 10-6× FL3.1765 (n=56, r2=0.967, p < 0.05). The subjective index of fullness of specimens was estimated as: 1 = empty (38.6%), 2 = <half full (47.37%), 3 = half full (3.51%), 4 = >half full (5.26%), and 5 = full (5.26%). For the stomachs with prey items, almost all the preys are pisces and the proportion of each prey groups are fishes (95.6%), cephalopods (2.05%), and crustaceans (0.02%). In total, 6 prey taxa were identified – 4 species of fish, 1 unidentified pisces, 1 unidentified crustacean, and 1 unidentified squid. The 4 fish species fall in the family of Carangidae, Clupeidae, Emmelichthyidae, and Hemiramphidae. -

Saltwater Recreational Fish Size and Bag Limits

FL: fork length. CFL: curved fork length LJFL: lower jar fork length. Measured from tip of lower jaw to tail fork. 1 Aggregate limit for Lane and Vermilion snappers, Gray trigger- fish, Almaco jack, and Tilefishes is 20/day. 2 Offshore landing permit: Tuna, Billfish, Swordfish, Amberjacks, Grouper, Hinds and Snapper (non-grey). 3 Must report Yellowfin Tuna landings. 4 Aggregate limit for all groupers (except Nassau, Goliath Warsaw, and Speckled hind) is 4/day. Check for seasons. All saltwater fish except tuna, garfish, and swordfish in possession must have the head and tailfin intact when set or put on shore from a vessel. The skin must be left on these fish. Federal regu- lations require that tails are to be on tunas. For all saltwater fish, the bag limit is also the possession limit, except for redfish and speckled trout. A two-day limit of these two species is allowed in possession on land but not on the water. Fisheries regulations are subject to change often. At the time of this printing, these regulations were correct. For more information, call your local Sea Grant marine extension agent in the Louisiana Cooperative Extension Service or LDWF enforcement agent. www.seagrantfish.lsu.edu Recreational Fish Recreational SALTWATER 2013 Louisiana Size & BagSize Limits SALTWATER RECREATIONAL FISH SIZE AND BAG LIMITS Species Minimum size Bag limit Black Drum 16 in.; only 1 over 27 in. 5/day Redfish 16 in.; only 1 over 27 in. 5/day Cobia 33 in.FL 2/day King Mackerel 24 in.FL 2/day Spanish Mackerel 12 in.FL 15/day Speckled Trout/Spotted Sea Trout 12 in. -

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

QUALITY STATUS REPORT 2010 Case Reports for the OSPAR List of threatened and/or declining species and habitats – Update Nomination and biomass of older fish since 1993. The reported catch for the East Atlantic and Atlantic bluefin tuna Mediterranean stocks in 2000 was 33,754 MT, Thunnus thynnus about 60% of the peak catch in 1996 although this is probably an under-estimate because of increasing uncertainty about catch statistics (ICCAT, 2002). The best current determination of the state of the stock is that the Spawning Stock Biomass is 86% of the 1970 level. This is similar to the results obtained in 1998 in terms of trends, but more optimistic in terms of current depletion. Nevertheless, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) Geographical extent considers that current catch levels are not OSPAR Regions: V sustainable in the long-term (ICCAT, 2002). Biogeographic zones:1,2,4-8 Region & Biogeographic zones specified for Sensitivity decline and/or threat: as above The Atlantic bluefin tuna has a slow growth rate, long life span (up to 20 years) and late The Atlantic bluefin tuna is an oceanic species age of maturity for a fish (4-5 years for the that comes close to shore on a seasonal basis. eastern stock) resulting in a large number of Current management regimes work on the juvenile classes. These characteristics make it basis of their being two stocks, an Eastern more vulnerable to fishing pressure than Atlantic and a Western Atlantic stock, although rapidly growing tropical tuna species (ICCAT, some intermingling is thought to occur along 2002). -

PROXIMATE and GENETIC ANALYSIS of BLACKFIN TUNA (T. Atlanticus)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. PROXIMATE AND GENETIC ANALYSIS OF BLACKFIN TUNA (T. atlanticus). Yuridia M. Núñez-Mata1, Jesse R. Ríos Rodríguez 1, Adriana L. Perales-Torres 1, Xochitl F. De la Rosa-Reyna2, Jesús A. Vázquez-Rodríguez 3, Nadia A. Fernández-Santos2, Humberto Martínez Montoya 1 * 1 Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria Reynosa Aztlán – Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 2 Centro de Biotecnología Genómica – Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 3 Centro de Investigación en Salud Pública y Nutrición – Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, Nuevo León. *Correspondence: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-3228-0054 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. ABSTRACT The tuna meat is a nutritious food that possesses high content of protein, its low content of saturated fatty acids makes it a high demand food in the world. The Thunnus genus is composed of eight species, albacore (T. alalunga), bigeye (T. obesus), long tail tuna (T. tonggol), yellowfin tuna (T. albacares), pacific bluefin tuna (T. orientalis), bluefin tuna (T. maccoyii), Atlantic bluefin tuna ( T. thynnus) and blackfin tuna (T. atlanticus). The blackfin tuna (BFT) (Thunnus atlanticus) represent the smallest species within the Thunnus genus. -

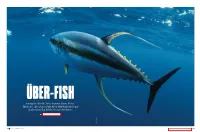

Among the World's Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also

ÜBER-FISH Among the World’s Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also Some of the Most Highly Evolved and Sophisticated of All the Ocean’s Predators BY DOUG OLANDER DANIEL GOEZ DANIEL 74 DECEMBER 2017 SPORTFISHINGMAG.COM 75 The Family Tree minimizes drag with a very low reduce the turbulence in the Tunas are part of the family drag coefficient,” optimizing effi- water ahead of the tail. Scombridae, which also includes cient swimming both at cruise Unlike most fishes with broad, mackerels, large and small. But and burst. While most fishes bend flexible tails that bend to scoop there are tunas, and then there their bodies side to side when water to move a fish forward, are, well, “true tunas.” moving forward, tunas’ bodies tunas derive tremendous That is, two groups don’t bend. They’re essentially thrust with thin, hard, lunate WHILE MOST FISHES BEND ( sometimes known as “tribes”) rigid, solid torpedoes. ( crescent-moon-shaped) tails dominate the tuna clan. One is And these torpedoes are that beat constantly, capable of THEIR BODIES SIDE TO SIDE Thunnini, which is the group perfectly streamlined, their 10 to 12 or more beats per second. considered true tunas, charac- larger fins fitting perfectly into That relentless thrust accounts WHEN MOVING FORWARD, terized by two separate dorsal grooves so no part of these fins for the unstoppable runs that fins and a relatively thick body. a number of highly specialized protrudes above the body surface. tuna make repeatedly when TUNAS’ BODIES DON’T BEND. The 15 species of Thunnini are features facilitate these They lack the convex eyes of hooked. -

Movements and Diving Behavior of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Thunnus Thynnus in Relation to Water Column Structure in the Northwestern Atlantic

Vol. 400: 245–265, 2010 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published February 11 doi: 10.3354/meps08394 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Movements and diving behavior of Atlantic bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus in relation to water column structure in the northwestern Atlantic Gareth L. Lawson1, 2,*, Michael R. Castleton1, Barbara A. Block1 1Tuna Research and Conservation Center, Stanford University, Hopkins Marine Station, 120 Oceanview Boulevard, Pacific Grove, California 93950, USA 2Present address: Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA ABSTRACT: We analyzed the movements and diving behavior in relation to water column structure of 35 electronically tagged Atlantic bluefin tuna (176 to 240 cm in length at tagging) during their spring–fall period of occupancy of the Gulf of Maine, Canadian Shelf, and neighboring off-shelf waters from 1999 to 2005. Tagged fish arriving in this study region in March–April initially occupied weakly stratified off-shelf waters along the northern Gulf Stream. As waters over the continental shelf warmed in June, the fish shifted onto the shelf. Sea surface temperatures occupied were relatively constant in both off- and on-shelf waters (April–September monthly medians varying from 16.1 to 19.0°C). Dives made in the stratified waters of the shelf during summer and fall were significantly more frequent (up to 180 dives d–1) and fast (descent rates up to 4.1 m s–1) than in weakly stratified off-shelf waters occupied during spring, defining dives as excursions below tag-derived estimates of the surface isothermal layer depth (ILD). The duration and depth of dives also decreased significantly in associa- tion with changing water column structure, from medians in off-shelf waters during April of 0.45 h and 77.0 m, respectively, to 0.16 h and 24.9 m in August. -

Skipjack Tuna, Yellowfin Tuna, Swordfish Western and Central

Skipjack tuna, Yellowfin tuna, Swordfish Katsuwonus pelamis, Thunnus albacares, Xiphias gladius ©Monterey Bay Aquarium Western and Central Pacific Troll/Pole, Handlines July 11, 2017 (updated January 8, 2018) Seafood Watch Consulting Researcher Disclaimer Seafood Watch® strives to have all Seafood Reports reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science and aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch® program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch® is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. Seafood Watch Standard used in this assessment: Standard for Fisheries vF2 Table of Contents About. Seafood. .Watch . 3. Guiding. .Principles . 4. Summary. 5. Final. Seafood. .Recommendations . 6. Introduction. 8. Assessment. 12. Criterion. 1:. .Impacts . on. the. species. .under . .assessment . .12 . Criterion. 2:. .Impacts . on. other. .species . .18 . Criterion. 3:. .Management . Effectiveness. .23 . Criterion. 4:. .Impacts . on. the. habitat. and. .ecosystem . .29 . Acknowledgements. 32. References. 33. Appendix. A:. Updated. January. 8,. .2017 . 36. 2 About Seafood Watch Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch® program evaluates the ecological sustainability of wild-caught and farmed seafood commonly found in the United States marketplace. Seafood Watch® defines sustainable seafood as originating from sources, whether wild-caught or farmed, which can maintain or increase production in the long-term without jeopardizing the structure or function of affected ecosystems. Seafood Watch® makes its science-based recommendations available to the public in the form of regional pocket guides that can be downloaded from www.seafoodwatch.org. The program’s goals are to raise awareness of important ocean conservation issues and empower seafood consumers and businesses to make choices for healthy oceans.