Access to Healthcare, Mortality and Violence in Democratic Republic of the Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Resource .Pdf

Mapping interests in conflict areas: Katanga Steven Spittaels Nick Meynen Summary “Mapping interests in conflict areas: Katanga” reports on the presence of (ex-) combatants in the Congolese province of Katanga. It focuses on two broad categories: the ‘Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo’ (FARDC) and the Mayi-Mayi militias. There is no significant presence of other armed groups in the region. After the surrender of the warlord Gédéon in May 2006, the large majority of the remaining Mayi-Mayi groups have demobilised and disarmed. They have chosen to reintegrate into civilian life but this has proven to be a difficult process. The FARDC are still represented all over the province although their numbers have been significantly reduced. It is an amalgam of the former government army (‘Forces Armées Congolaises’, FAC) and the different rebel armies that fought during the Congo wars. The positions of the (ex-) combatants in the region are shown on a first set of maps that accompanies the report. Their possible interests are indicated on a second one. The maps and the report focus on four regions where security problems are persisting into 2007. In the Northern part of Katanga the situation is particularly interesting in the territory of Nyunzu. Two Mayi-Mayi groups, who have not been disarmed yet, operate in the area. However, the biggest threat to the civilian population in the region are the FARDC, who took a specific interest in the Lunga gold mine at least until March 2007. In the Copperbelt there has never been a Mayi-Mayi presence, not even throughout the Congo wars. -

Deforestation and Forest Degradation Activities in the DRC

E4838 V5 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO MINISTRY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT, NATURE CONSERVATION AND TOURISM Public Disclosure Authorized STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE REDD+ PROCESS Public Disclosure Authorized BASELINE REPORT STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE REDD+ Public Disclosure Authorized PROCESS Public Disclosure Authorized October 2014 STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE REDD+ PROCESS in the DRC INDEX OF REPORTS Environmental Analysis Document Assessment of Risks and Challenges REDD+ National Strategy of the DRC Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Report (SESA) Framework Document Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) O.P. 4.01, 4.04, 4.37 Policies and Sector Planning Documents Pest and Pesticide Cultural Heritage Indigenous Peoples Process Framework Management Management Planning Framework (FF) Resettlement Framework Framework (IPPF) O.P.4.12 Policy Framework (PPMF) (CHMF) O.P.4.10 (RPF) O.P.4.09 O.P 4.11 O.P. 4.12 Consultation Reports Survey Report Provincial Consultation Report National Consultation of June 2013 Report Reference and Analysis Documents REDD+ National Strategy Framework of the DRC Terms of Reference of the SESA October 2014 Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment SESA Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Note ........................................................................................................................................ 9 1. Preface ............................................................................................................................................ -

Mai-Ndombe Province: a REDD+ Laboratory in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

RIGHTS AND RESOURCES INITIATIVE | MARCH 2018 Rights and Resources Initiative 2715 M Street NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20007 P : +1 202.470.3900 | F : +1 202.944.3315 www.rightsandresources.org About the Rights and Resources Initiative RRI is a global coalition consisting of 15 Partners, 7 Affiliated Networks, 14 International Fellows, and more than 150 collaborating international, regional, and community organizations dedicated to advancing the forestland and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. RRI leverages the capacity and expertise of coalition members to promote secure local land and resource rights and catalyze progressive policy and market reforms. RRI is coordinated by the Rights and Resources Group, a non-profit organization based in Washington, DC. For more information, please visit www.rightsandresources.org. Partners Affiliated Networks Sponsors The views presented here are not necessarily shared by the agencies that have generously supported this work, or all of the Partners and Affiliated Networks of the RRI Coalition. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0. – 2 – Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................... -

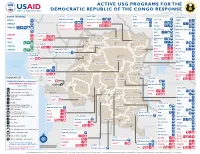

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

DR Congo 2015 Update

Analysis of the interactive map of artisanal mining areas in eastern DR Congo 2015 update International Peace Information Service (IPIS) 1 Editorial Analysis of the interactive map of artisanal mining areas in eastern DR Congo: 2015 update Antwerp, October 2016 Front Cover image: Cassiterite mine Malemba-Nkulu, Katanga (IPIS 2015) Authors: Yannick Weyns, Lotte Hoex & Ken Matthysen International Peace Information Service (IPIS) is an independent research institute, providing governmental and non-governmental actors with information and analysis to build sustainable peace and development in Sub-Saharan Africa. The research is centred around four programmes: Natural Resources, Business & Human Rights, Arms Trade & Security, and Conflict Mapping. Map and database: Filip Hilgert, Alexandre Jaillon, Manuel Claeys Bouuaert & Stef Verheijen The 2015 mapping of artisanal mining sites in eastern DRC was funded by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) and PROMINES. The execution of the mapping project was a collaboration between IPIS and the Congolese Mining Register (Cadastre Minier, CAMI). The analysis of the map was funded by the Belgian Development Cooperation (DGD). The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of IPIS and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of IOM, PROMINES, CAMI or the Belgian government. 2 Table of contents Editorial ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................. -

콩고민주공화국 광업 및 광물부존 현황 Mining and Mineral Resources of DR-Congo

기술정보 콩고민주공화국 광업 및 광물부존 현황 Mining and Mineral Resources of DR-Congo 양석준, 고상모, 박성원 한국지질자원연구원 광물자원연구본부 콩고 민주공화국은 코발트, 구리, 다이아몬 2011년 국내 총생산에서 11.5 %에 해당했으며, 드, 탄탈륨 및 주석의 생산에서 전세계적으로 제조 부분은 5.2 %였다. 콩고민주공화국에서 중요한 역할을 담당하고 있다(그림 1). 2012년 는 180에서 200만 명이 사광상에서 광물을 채 콩고민주공화국의 코발트 생산량은 전세계 생 취하고 있으며, 이들 중 800,000에서 100만 명 산량의 55 %, 산업용 다이아몬드는 21 %, 탄탈 은 다이아몬드 채광, 약 130,000명의 광부는 오 륨은 12 %, 보석-등급 다이아몬드는 5 %, 구리 리엔탈(Orientale) 주와 이투리 주(Ituri Interim 는 3 %; 주석은 2 %에 달했다. 콩고민주공화국 Administration)지역의 금광에서 일하고 있다. 의 코발트 매장량은 전세계 코발트 매장량의 마니에마(Maniema), 북키부(Nord-Kivu) 및 남 45 %에 해당한다. 채광 및 광물처리 부문은 키부(Sud-Kivu) 주에서 니오븀, 탄탈륨, 주석 그림 1. 콩고민주공화국 자원분포도. 광물과 산업 35 기술정보 및 텅스텐 채광에 고용된 광부들의 수는 그 생 Reform and Consumer Protection Act)을 통과시 산량 감소로 인해 2011년과 2012년 사이에 크 켰는데, 여기엔 콩고민주공화국 동부의 군사 게 감소했다. 작전에 대한 자금 조달을 위해 광물을 사용하는 이 기술정보지에 소개될 내용에 대한 자원 것과 관련한 규정들이 포함되어 있다. 미 연방 정보 자료원은 USGS에서 2014년도에 발간한 증권 거래 위원회(U.S. Securities and Exchange 콩고민주공화국 지역의 2012년 광물 연감이다. Commission, SEC)는 2012년 8월 도트 프랭크 법안(Dodd-Frank Act)에 따라 최종적인 형태의 정부 정책 및 프로그램 법률을 발표했다. 제안된 규정에 따라, SEC에 등록된 주석 2002년에 콩고민주공화국 의회는 1981년 7 (cassiterite), 컬럼바이트 탄탈석(columbite- 월 11일자 Law No. 81–013를 대체하는 2002년 tantalite), 금(gold), 또는 철망간중석(wolframite) 7월 11일자 Law No. -

The Mai Ndombe Redd+ Project Second Monitoring & Implementation Report (M2)

MONITORING REPORT: CCB Version 2, VCS Version 3 THE MAI NDOMBE REDD+ PROJECT SECOND MONITORING & IMPLEMENTATION REPORT (M2) Document Prepared by Wildlife Works Carbon Project Title The Mai Ndombe REDD+ Project Project ID 934 Version 4.3 Report ID 1 Date of Issue 22-October-2017 Project Location Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mai Ndombe Province Wildlife Works Carbon Project Proponent(s) Jeremy T. Freund [email protected]; 415-331-8081 Jeremy T. Freund, Simon Bird and Mike Korchinsky Prepared By Wildlife Works Carbon CCB v2.0, VCS v3.4 1 MONITORING REPORT: CCB Version 2, VCS Version 3 EPIC Sustainability Services K. Suryanarayana Murthy Validation/Verification Body [email protected] +91 9845759000 GHG Accounting/Crediting 14 March 2011 – 13 March 2041 Period 30-year crediting period Monitoring Period of this 01 November 2012 – 31 December 2016 Report Validation: 06 December 2011 History of CCB Status Verification (m1): 06 December 2011 Climate and Biodiversity Gold Level Criteria The Project will conserve flora and fauna within the Project Area. Protecting these 2 former logging concessions will maintain critical forested area and the ecosystem services that it provides, as well as rehabilitate habitat for endangered charismatic animals such as the Bonobo and Forest Elephant. By protecting the native forest, the Project will also increase the resilience of the ecosystem to the effects of climate change. Section GL1.4 of the CCB PDD exemplifies many additional Project Activities that will help both local communities and biodiversity to minimize and adapt to expected climate change impacts. Improved seed distribution and training on improved Gold Level Criteria agricultural methods will lead to increased yields and adaptation to changes in rainfall, the timing of growing seasons, and changing temperatures. -

Returns Outnumber New Displacements in the East

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO: Returns outnumber new displacements in the east A profile of the internal displacement situation 26 April, 2007 This Internal Displacement Profile is automatically generated from the online IDP database of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). It includes an overview of the internal displacement situation in the country prepared by the IDMC, followed by a compilation of excerpts from relevant reports by a variety of different sources. All headlines as well as the bullet point summaries at the beginning of each chapter were added by the IDMC to facilitate navigation through the Profile. Where dates in brackets are added to headlines, they indicate the publication date of the most recent source used in the respective chapter. The views expressed in the reports compiled in this Profile are not necessarily shared by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The Profile is also available online at www.internal-displacement.org. About the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, established in 1998 by the Norwegian Refugee Council, is the leading international body monitoring conflict-induced internal displacement worldwide. Through its work, the Centre contributes to improving national and international capacities to protect and assist the millions of people around the globe who have been displaced within their own country as a result of conflicts or human rights violations. At the request of the United Nations, the Geneva-based Centre runs an online database providing comprehensive information and analysis on internal displacement in some 50 countries. Based on its monitoring and data collection activities, the Centre advocates for durable solutions to the plight of the internally displaced in line with international standards. -

UNICEF Democratic Republic of the Congo – FLASH REPORT #2

UNICEF Democratic Republic of the Congo – FLASH REPORT #2 1 March 2013 Note: In addition to a complete monthly situation report, UNICEF DRC will now provide Flash Reports every mid-month to highlight critical humanitarian situations. POLITICAL, SECURITY & HUMANITARIAN DEVELOPMENTS NORTH KIVU On 24 February African leaders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia signed a U.N.-mediated deal allowing for the deployment of a new intervention brigade to take on rebel groups in the eastern DRC. The upcoming deployment of the brigade of several thousand soldiers has raised concerns among humanitarians regarding protection of civilians as well as humanitarian space and access. Armed clashes were reported on 24 February between M23 factions loyal to Jean-Marie Runiga, leader of the movement’s political wing, and Sultani Makenga, their military commander, in Rutshuru. Ten people were killed and more wounded, according to media reports. Official communication from the M23 military command on 27 February indicate that Runiga has been removed from his role within the movement, and there are media reports of gunfire between pro-Runiga and pro-Makenga factions around Kibumba, just north of Goma, on 28 February. This split in the M23 raises fears of increased violence and the viability of the peace process envisaged by the Addis accords. According to education authorities, some 1,000 households displaced from Rutshuru during the fighting have settled in schools around Kanyaruchinya, some 10 kilometres from Goma. Combat broke out 27 February between FARDC forces and the APCLS armed group in the area of Kitchanga (Masisi territory), resulting in 19 civilian casualties according to UNDSS. -

![Congo (Kinshasa) [Advance Release]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5950/congo-kinshasa-advance-release-1505950.webp)

Congo (Kinshasa) [Advance Release]

2012 Minerals Yearbook CONGO (KINSHASA) [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior June 2014 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF CONGO (KINSHASA) By Thomas R. Yager The Democratic Republic of the Congo [Congo (Kinshasa)] and increased the number of known artisanal diamond mining played a globally significant role in the world’s production sites to 667 from 254. The program was also designed to track of cobalt, copper, diamond, tantalum, and tin. In 2012, the diamond production from mining to exportation (Diamond country’s share of the world’s cobalt production amounted to Development Initiative, 2012). 55%; industrial diamond, 21%; tantalum, 12%; gem-quality In July 2010, the U.S. Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall diamond, 5%; copper, 3%; and tin, 2%. Congo (Kinshasa) Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), accounted for about 45% of the world’s cobalt reserves. In which contains provisions concerning the use of minerals terms of export value, crude petroleum also played a significant to finance military operations in eastern Congo (Kinshasa). role in the domestic economy. The country was not a globally The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued significant consumer of minerals or mineral fuels (Carlin, 2013; regulations in final form in accordance with the Dodd-Frank Act Edelstein, 2013; Olson, 2013a, b; Papp, 2013; Shedd, 2013). in August 2012 (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2012, p. 56274–56275). Minerals in the National Economy Under the proposed regulations, all companies registered with the SEC that sold products containing cassiterite, columbite- The mining and mineral processing sector accounted for an tantalite, gold, or wolframite were required to disclose whether estimated 11.5% of the gross domestic product in 2011 (the these minerals originated from Congo (Kinshasa) or adjoining latest year for which data were available), and the manufacturing countries. -

Mapping Conflict Motives

Mapping Conflict Motives: Katanga Update: May- September 2008 Steven Spittaels & Filip Hilgert 1 Editorial Research and editing: Steven Spittaels & Filip Hilgert Layout: Anne Hullebroeck Antwerp 5 January 2009 Caption photo Front Page: Artisanal cassiterite mine near Mitwaba, 2008 (Photo: Partner IPIS) Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following partner organisations for their contributions to the research: • Asadho/katanga • Padholik • Promotion des populations Indigènes (PPI) • And one other organisation 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 The Mayi-Mayi and the ‘DDR’ process 5 The North 6 Presence of armed groups 6 Motives of armed groups 6 Presence of FARDC 7 Motives of FARDC 7 The Copperbelt 8 Presence of FARDC 8 Motives of FARDC 8 The Centre 10 Presence of armed groups 10 Motives of armed groups 10 Presence of FARDC 10 Motives of FARDC 11 The East 12 Presence of armed groups 12 Presence of FARDC 12 Motives of FARDC 12 Conclusion and recommendations 13 New maps 14 Annexe: List of abbreviations 14 3 Introduction With the renewed intensification of hostilities in North Kivu, and to a lesser extent in Ituri, security problems in Katanga have stopped figuring in the news. To a certain extent this is of course justified. The humanitarian situation in the Kivus is dramatic and requires all the attention it can get. Human rights violations in Katanga have decreased1. However, with MONUC gradually retreating from the province2 the international presence diminishes and with it the number of eyes and ears of observers in the field. Nonetheless, for the future several security hazards remain. For one, the impact of the economic crisis on Katanga is enormous. -

PBG Quarterly Report 'Programme De Bonne

/’ PBG Quarterly Report ‘Programme de Bonne Gouvernance’ Contract No. DFD-I-00-08-00071-00 Task Order No. DFD-I-01-0800071-00 USAID Project Office: USAID/EA/RAAO Quarterly Report 13 October 1, 2012 – December 31, 2012 January 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. PBG – FY 2013 Quarterly Report 13 - Page 1 of 25 Task Order Quarterly Report Programme de Bonne Gouvernance First Quarterly Report FY 2013 October 1, 2012 – December 31, 2012 Quarterly 13 for Task Order # DFD-I-01-0800071-00 October 1, 2007 – September 30, 2008 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. PBG – FY 2013 Quarterly Report 13 - Page 2 of 25 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I INTRODUCTION 04 SECTION II POLITICAL BACKGROUND 05 SECTION III SUMMARY OF PERFORMANCE ADVANCES 08 SECTION IV OUTSTANDING ISSUES, CHALLENGES & OPPORTUNITIES 23 SECTION V PLANNED ACTIVITIES FOR NEXT QUARTER 24 LIST OF APPENDICES ANNEX 1 Year 1 Activities Update – Chart format as defined in FY 2013 Workplan ANNEX 2 PMP Results Update ANNEX 3 Calendar of Activities – Quarter 1 of FY 2013 ANNEX 4 PBG Success Stories ANNEX 5 Workshop Scanned Participation lists PBG – FY 2013 Quarterly Report 13 - Page 3 of 25 I – INTRODUCTION In October 2009, the life of the ‘Programme de Bonne Gouvernance’ (PBG) began. This thirteenth quarterly report, covering activities from October 1, 2012 to December 31, 2012, focuses on the first quarter of implementation for Year 4 (FY 2013) workplan activities of this $36,251,768 five-year (three years with two option years) program whose purpose is to improve management capacity and accountability of select legislatures and local governments.