Two Workers, Worlds Apart, Share Uncertain Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kraft Foods Inc(Kft)

KRAFT FOODS INC (KFT) 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filed on 02/28/2011 Filed Period 12/31/2010 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 (Mark one) FORM 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2010 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-16483 Kraft Foods Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 52-2284372 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) Three Lakes Drive, Northfield, Illinois 60093-2753 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 847-646-2000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A Common Stock, no par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes x No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Note: Checking the box above will not relieve any registrant required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act from their obligations under those Sections. -

Mondelēz Union Network

Mondelēz Union Network What is ? Mondelez is a global snack foods company which came into being on October 2, 2012 when the former Kraft Foods Inc. was split into two, resulting in the creation of two separate companies, both headquartered in the USA. Mondelēz took the “snacks” products (biscuits, confectionery, salty crackers, nuts, gum, Tang), giving it about two-thirds the revenue of the former Kraft. The remaining “grocery” products were stuffed into a North American (only) company now known as Kraft Foods Group. Former Kraft CEO Irene Rosenfeld now heads up Mondelēz. If you worked for the former Kraft or one of its subsidiaries manufacturing or distributing snack products, including former Danone or Cadbury products, you now work for Mondelēz or one of its subsidiaries. In some countries, the name change will not be immediate. Mondelēz Kraft Foods Group Oreo, Chips Ahoy, Fig Kraft macaroni and cheese Newtons, SnackWell’s, Stove Top stuffing Nilla wafers, Mallomars Kool-Aid and Capri Sun Nabisco crackers including drinks Ritz, Triscuit, Teddy Grahams, Deli brands including Oscar Honey Maid, Premium Mayer, Louis Rich, saltines, Planters nuts, Lunchables, Deli Creations, Cheese Nips, Wheat Thins, Claussen pickles Lu biscuits Philadelphia cream cheese Philadelphia cream cheese Kraft, Velveeta and Cracker Toblerone chocolate, Milka Barrel cheese candy bars, Cadbury, Green and Black’s Jell-O Trident/ Dentyne gum Cool Whip/Miracle Whip Halls A-1 steak sauce, Grey Poupon mustard Tang Vegemite Jacobs coffee Maxwell House coffee 888 Brand names in red are ‘power brands’ each generating revenue over USD 1 billion In North America, Maxwell House coffee is ‘grocery’ (Kraft Foods Group), but elsewhere coffee is Mondelēz. -

Product Guide January - June 2020 PRODUCT GUIDE JAN - JUN 2020 Welcome

Disclaimer Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this list, information contained in this catalogue is given in good faith. All items featured within this brochure are subject to availability. Size and product information are quoted as approximate and for guidance only. Pictures are for illustration purposes only. Head Office Depot Wakefield Depot Serving Central & Southern areas Serving Northern areas Steelmans Road Premier Park Jamesbridge Unit 3, Darlaston, Wednesbury Premier Way West Midlands Wakefield WS10 9UZ LS26 8ZA 0121 526 8400 www.afblakemore.com/food-service/welcome Product Guide January - June 2020 PRODUCT GUIDE JAN - JUN 2020 Welcome... Blakemore foodservice is part of the wider Blakemore group with a turnover of over £1billion. The Blakemore group has been in existence for over 100 years and is headed up by Peter Blakemore who is Chairman and also grandson of the original founder. • The whole of the business is based on strong company values • Maximise Staff potential and their contribution to the company’s success • Give great service to all our customers and add value to our trade partners • Make a significant positive contribution to the community • Attain excellence in everything we do • Behave with honesty and integrity in everything we do Here at Blakemore Foodservice, we pride ourselves Brexit is still looming, however rest assured that on providing great value and a wide range of we have a robust plan in place to minimise impact products to meet our customers’ needs, delivering all to supply during this period. We will endeavour to across England, Scotland and Wales. -

This Toolkit of Materials Is Developed and Brought to You by NABISCO As a Professional Resource

This is for layout purposes only please use the web assets provided in the file folder ONCE UPON A WHOLE GRAIN… According to the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, at least half of all grains eaten should be whole grains. This equates to at least 48g of whole grains a day. Yet, few Americans meet this recommendation, citing taste, time, and lack of skills to prepare as key barriers. This toolkit aims to arm you with tools to help individuals reach the whole grain goal by providing fact-based information in a lighthearted way—with fairy tales! We’ll show that there are many delicious and convenient ways to enjoy foods made with whole grains. PROGRAM AT A GLANCE KEY MESSAGES PRODUCT GUIDE DEMO INSPIRATIONS Explains why NABISCO is rewriting classic fairy Provides talking points on the importance of Presents the variety of delicious and Inspires fun, creative demonstrations and tales to bring the whole grains story to life. whole grains, consumer obstacles, and convenient NABISCO products made with learning activities that feature simple recipes solutions. whole grains that can be enjoyed at home or using NABISCO products made with whole Program At A Glance pdf on-the-go, as part of a balanced diet. grains. Key Messages pdf Product Guide pdf Demo Inspirations pdf RECIPES EDITORIAL CALENDAR 7DAY GUIDE SHOPPING LIST Helps shoppers choose foods from the five Provides delicious and easy ways to help Provides monthly themes and tweets you can Shows how NABISCO products can help food groups for a balanced diet, including consumers enjoy whole grains at meal time or use to keep your whole grain messages fresh consumers reach 48 grams or more of whole foods made with whole grains. -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

Grocery Goliaths

HOW FOOD MONOPOLIES IMPACT CONSUMERS About Food & Water Watch Food & Water Watch works to ensure the food, water and fish we consume is safe, accessible and sustainable. So we can all enjoy and trust in what we eat and drink, we help people take charge of where their food comes from, keep clean, affordable, public tap water flowing freely to our homes, protect the environmental quality of oceans, force government to do its job protecting citizens, and educate about the importance of keeping shared resources under public control. Food & Water Watch California Office 1616 P St. NW, Ste. 300 1814 Franklin St., Ste. 1100 Washington, DC 20036 Oakland, CA 94612 tel: (202) 683-2500 tel: (510) 922-0720 fax: (202) 683-2501 fax: (510) 922-0723 [email protected] [email protected] foodandwaterwatch.org Copyright © December 2013 by Food & Water Watch. All rights reserved. This report can be viewed or downloaded at foodandwaterwatch.org. HOW FOOD MONOPOLIES IMPACT CONSUMERS Executive Summary . 2 Introduction . 3 Supersizing the Supermarket . 3 The Rise of Monolithic Food Manufacturers. 4 Intense consolidation throughout the supermarket . 7 Consumer choice limited. 7 Storewide domination by a few firms . 8 Supermarket Strategies to Manipulate Shoppers . 9 Sensory manipulation . .10 Product placement . .10 Slotting fees and category captains . .11 Advertising and promotions . .11 Conclusion and Recommendations. .12 Appendix A: Market Share of 100 Grocery Items . .13 Appendix B: Top Food Conglomerates’ Widespread Presence in the Grocery Store . .27 Methodology . .29 Endnotes. .30 Executive Summary Safeway.4 Walmart alone sold nearly a third (28.8 5 Groceries are big business, with Americans spending percent) of all groceries in 2012. -

2005 Annual Report

Kraft Foods Inc. One sip, one snack, one meal... one delicious moment at a time. 2005 Annual Report Kraft Foods Inc. 2005 Annual Report While Kraft is the world’s second-largest food and beverage company, we know that what matters most are the individual moments each of our consumers shares with our brands. That’s why consumers are the focus of everything we do. Whether they are connecting over coffee with friends, or enjoying a family meal or treat at the end of the day, we win when we make those moments a bit tastier, easier or better-for-them. Hundreds of millions of times a day, around the world, we’re helping people eat and live better. The Brands The World Loves Snacks Crunchy, sweet, savory, satisfying. Whatever the flavor, consumers hunger for great-tasting snacks that are delicious, convenient and increasingly more nutritious. In the snacks sector, Kraft’s key brands include Milka, Planters, Oreo, Ritz, Chips Ahoy!, Trakinas, Wheat Thins and Côte d’Or. Beverages Around the world, Kraft offers an array of beverage choices to quench every thirst – from refreshment to nutrition to relaxation. In the beverages sector, our key brands include Carte Noire, Gevalia, Jacobs, Maxwell House, Capri Sun, Kool-Aid, Tang and Clight. Cheese & Dairy At breakfast, dinner and every eating occasion in between, cheese and dairy products are an important and delicious part of consumers’ diets around the world. In the cheese & dairy sector, Kraft’s key brands include Kraft, Philadelphia, Velveeta, Cracker Barrel, Breakstone’s and Dairylea. Grocery Whether it’s a salad dressing, breakfast cereal, dessert or condiment, Kraft has the grocery brands that feature prominently in consumers’ shopping baskets. -

Nikita to Make Statement Woi Follow the Meeting

X. {■ WEDNESDAY, JUNE IT, 19» Average Dally Net Press Run PAGE TWENTY-POUR .r iHanrt|p0tpr lEmnins Efralb Far toe WssK BaOM : x May ttfd. 1W» 12,925 About Town MsatbMr tos Audit Onr«M st OlreolnUon O u o( t)M Koat Holy Mancha$ter~^A City of Village Chflrm KoMnr Orel* will noM lU umuai dlnnw tonistit at 7:S0 at Okvay’a RetUiirant. M «m b«r» art VOls LXXVIII, NO. 220 (TW ENTY-FOUR PAGES— TWO SECTTIONS) MANCHESTER. CONN„ THURSDAY, JUNE 18. 1W9 Mntiitod to brtof their donations fo r toe Greater Hartford Catholic h llh aehoel buUdlnf fund or to eeatact Mrs. JamN letber. GREEN DOUBLE Governor Long D m Canter Church Mothers Queen, Philip Flying Chib family picnic scheduled for toolsiit has been canceled. Put in Hospital Minrhsstrr Barracks. Veterans CASH SALES! «( Worid War I. 4Ad lU tiSdiea IMTH Atlantic for 45-Day In Louisiana Auxiliary, Wiu admit to- member ship toe lariest class of candl* dates in their history Sunday New Orleans, June 18 (/P) aftamoon at the VFW Hwne. A — A -w ea ry but determined membership drive has been con TAKE ADVANTAGE Trip Across Canada Gov. Earl K. lAing was back ducted duTinc the past month. All sum m er h an d bag s in Louisiana today, confined candidates are asked to be pres OP J. W. HALE'S ent at 2:80. A Fathers Day social JUNE FABRIC SALE St. Johns., Nfid., June 18t The Queen's.plane took off from to a $22.50-a-day hospital .Nikita to Make Statement wOI follow the meeting. -

Peanut/Nut-Free Snack List

Peanut/Nut‐Free Snack List Fruits Chocolate (not Peanut Butter Crème or Oreo Cakesters) All fresh fruits Nilla Wafers Dole and Del Monte fruit bowls Teddy Grahams (chocolate, honey, chocolate Sun Maid Raisins (not chocolate or yogurt chip and cinnamon) covered) Chips A‐Hoy (not Mini’s) Craisins Pepperidge Farm – Milano, Chessmen, Applesauce cups Shortbread and Sugar Cookies, Soft Baked Chocolate Chunk and Oatmeal Vegetables Keebler – Grasshoppers, Butter Cookies All fresh vegetables including: Nabisco – Barnum Animal Crackers, Oatmeal and Iced Oatmeal Cookies, Fig Newtons Carrots with ranch dip Rice Krispy Treats (plain only) Celery sticks with cream cheese or ranch dip Nutri Grain bars (e.g., strawberry, apple, blueberry, cherry) Gummy Snacks NutriGrain Twists bars Betty Crocker and Kellogg’s fruit snacks Special K bars (strawberry, vanilla and chocolate including: only) Fruit Roll‐ups Fruit by the Foot Salty Snacks Fruit Gushers Rold Gold Pretzels Stackerz Ruffles and Lays Potato Chips (not Mike Sells) Sun Chips Cookies Fritos NO GRANOLA BARS! Doritos (not crackers) Oreos: Original, Double Stuf, Mint Crème, Tostitos Chocolate Crème, Golden Oreos, Golden with IMPORTANT: Due to continual changes in manufacturer packaging, please read the ingredient label of all snacks, including those on this list, to ensure that it does not contain any of the following: peanuts/nuts, peanut/nut butter, peanut oil, peanut/nut flour, peanut/nut meal, or any variety of the statements, “Contains peanuts,” “May contain traces of peanuts/nuts,” or “Manufactured -

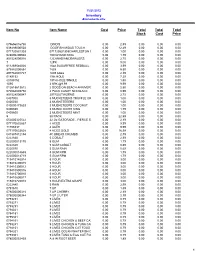

NH Convenient Database

11/21/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 075656016798 DINO'S 0.00 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 638489000503 DOGFISH MIDAS TOUCH 0.00 12.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 071720531303 071720531303CHARLESTON CHEW VANILLA 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 028000206604 100 GRAND KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000016 12CANADIANCRAWLERS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 7 12PK 0.00 9.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 611269546026 16oz SUGARFREE REDBULL 0.00 3.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 879982000854 1839 0.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 897782001727 1839 tubes 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 0189152 19th HOLE 0.00 7.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 s0189152 19TH HOLE SINGLE 0.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 1095 2 6PK @9.99 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 012615613612 2 DOGS ON BEACH ANNIVERSARY CARD 0.00 2.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 072084003758 2 PACK CANDY NECKLACE 0.00 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000047 20TROUTWORMS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0407000 3 MUCKETEERS TRUFFLE CRISP 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0400030 3 MUSKETEEERS 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 040000473633 3 MUSKETEERS COCONUT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0406030 3 MUSKETEERS KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0405600 3 MUSKETEERS MINT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 5 30 PACK 0.00 22.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 052000325522 32 Oz GATORADE - FIERCE STRAWBERRY 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170632867 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 71706337 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170633628 4 ACES GOLD 0.00 16.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 041387412154 4C BREAD CRUMBS 0.00 2.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222830 5 COBALT 0.00 2.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 022000013170 5 GUM 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222820 5 GUM COBALT -

View Annual Report

® ℠ Morningstar Document Research FORM 10-K KRAFT FOODS INC - KFT Filed: February 25, 2010 (period: December 31, 2009) Annual report which provides a comprehensive overview of the company for the past year UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 (Mark one) FORM 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-16483 Kraft Foods Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 52-2284372 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) Three Lakes Drive, Northfield, Illinois 60093 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 847-646-2000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A Common Stock, no par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ⌧ No � Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes � No ⌧ Note: Checking the box above will not relieve any registrant required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act from their obligations under those Sections. -

Safe Snack Guide

Foods Free of Peanuts and Tree Nuts – Many Free of the Top 8 Updated December 5, 2017 PEANUT BUTTER ALTERNATIVES & SPREADS • 88 Acres Pumpkin Seed Butter [OR,GF,NG] • 88 Acres Sunflower Seed Butter [OR,GF,NG] – Dark Chocolate, Vanilla Spice • Sneaky Chef No-Nut Butter [K] – Chocolate, Creamy • PASCHA Make Me Smile Chocolate Spread [K,GF,NG] – No Sugar Added, Original • SunButter Sunflower Butter [K] – Creamy, Natural Creamy, Natural Crunch, Natural No Sugar Added, Organic Unsweetened • P-Nut Free PB&J Sandwich – Grape, Strawberry • Don't Go Nuts Spread [K,OR,GF,NG] – Chocolate, Lightly Sea Salted, Pure Unsalted, Simply Cinnamon, Slightly Sweet • SunButter On the Go Single Cups [K] • SunButter Sunflower Seed Spread [K] • WOWBUTTER [K] – Creamy, Crunchy ▲ SunWise SunButter and Grape Jelly Sandwich COFFEE • Gerbs Ground Coffee [K,GF,NG] – Espresso Joe, French Roast, Italian Dark Roast BREAD, BAGELS AND ROLLS • Mo’Pweeze Bakery Sandwich Bread – Buckwheat, Millet-Rice, Potato • The Greater Knead Bagels [K] – Cinnamon Raisin, Everything, Plain • Lancaster Food Co Certified Organic Sandwich Bread [OR] – 100% Whole Wheat with Honey, Cinnamon Raisin, Rye, Seeded Multigrain, Sprouted Multigrain, White NUTRITION, CEREAL & ENERGY BARS • 88 Acres Craft Seed Bar [GF,NG] – Apple Ginger, Chocolate Sea Salt, Triple Berry • Enjoy Life Baked Chewy Bars [K,GF,NG] – Caramel Apple, Caramel Blondie, Carrot Cake, Cocoa Loco, Lemon Blueberry Poppy Seed, SunSeed Crunch • Enjoy Life ProBurst Bites [K,GF,NG] – Cinnamon Spice, Cranberry Orange, Mango Habanero, SunSeed