The Vedas – June 30 What Are They? What Do They Contain?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Akasha (Space) and Shabda (Sound): Vedic and Acoustical Perspectives

1 Akasha (Space) and Shabda (Sound): Vedic and Acoustical perspectives M.G. Prasad Department of Mechanical Engineering Stevens Institute of Technology Hoboken, New Jersey [email protected] Abstract A sequential ordering of five elements on their decreasing subtlety, namely space, air fire, water and earth is stated by Narayanopanishat in Atharva Veda. This statement is examined from an acoustical point of view. The space as an element (bhuta) is qualified by sound as its descriptor (tanmatra). The relation between space and sound and their subtle nature in reference to senses of perception will be presented. The placement of space as the first element and sound as its only property will be discussed in a scientific perspective. Introduction The five elements and their properties are referred to in various places in the Vedic literature. An element is the substance (dravya) which has an associated property (of qualities) termed as guna. The substance-property (or dravya- guna) relationship is very important in dealing with human perception and its nature through the five senses. Several Upanishads and the darshana shastras have dealt with the topic of substance-property (see list of references at the end). The sequential ordering of the five elements is a fundamental issue when dealing with the role of five elements and their properties in the cosmological evolution of the universe. At the same time the order of the properties of elements is also fundamental issue when dealing with the perception of elements is also a through five senses. This paper focuses attention on the element-property (or dravya-guna) relation in reference to space as the element and sound as its property. -

Kirtan Leelaarth Amrutdhaara

KIRTAN LEELAARTH AMRUTDHAARA INSPIRERS Param Pujya Dharma Dhurandhar 1008 Acharya Shree Koshalendraprasadji Maharaj Ahmedabad Diocese Aksharnivasi Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Hariswaroopdasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Dharmanandandasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) PUBLISHER Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple (Kenton-Harrow) (Affiliated to Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj – Kutch) PUBLISHED 4th May 2008 (Chaitra Vad 14, Samvat 2064) Produced by: Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton Harrow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. © Copyright 2008 Artwork designed by: SKSS Temple I.T. Centre © Copyright 2008 Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton, Harrow Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple Westfield Lane, Kenton, Harrow Middlesex, HA3 9EA, UK Tel: 020 8909 9899 Fax: 020 8909 9897 www.sksst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 271034 i ii Forword Jay Shree Swaminarayan, The Swaminarayan Sampraday (faith) is supported by its four pillars; Mandir (Temple), Shastra (Holy Books), Acharya (Guru) and Santos (Holy Saints & Devotees). The growth, strength and inter- supportiveness of these four pillars are key to spreading of the Swaminarayan Faith. Lord Shree Swaminarayan has acknowledged these pillars and laid down the key responsibilities for each of the pillars. He instructed his Nand-Santos to write Shastras which helped the devotees to perform devotion (Bhakti), acquire true knowledge (Gnan), practice righteous living (Dharma) and develop non- attachment to every thing material except Supreme God, Lord Shree Swaminarayan (Vairagya). There are nine types of bhakti, of which, Lord Shree Swaminarayan has singled out Kirtan Bhakti as one of the most important and fundamental in our devotion to God. -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

9789004400139 Webready Con

Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 19 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Selected Studies By Henk Bodewitz Edited by Dory Heilijgers Jan Houben Karel van Kooij LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bodewitz, H. W., author. | Heilijgers-Seelen, Dorothea Maria, 1949- editor. Title: Vedic cosmology and ethics : selected studies / by Henk Bodewitz ; edited by Dory Heilijgers, Jan Houben, Karel van Kooij. Description: Boston : Brill, 2019. | Series: Gonda indological studies, ISSN 1382-3442 ; 19 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019013194 (print) | LCCN 2019021868 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004400139 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004398641 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Hindu cosmology. | Hinduism–Doctrines. | Hindu ethics. Classification: LCC B132.C67 (ebook) | LCC B132.C67 B63 2019 (print) | DDC 294.5/2–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013194 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 1382-3442 ISBN 978-90-04-39864-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-40013-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Henk Bodewitz. -

The Four Vedas

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com The Four Vedas Rigveda contains mainly mantras in praise of various vedic deities and prayers to them. It is divided in two ways. 8 ashtakas comprising of 64 adhyayas ORversesverses 10 mandalas comprising of 85 anuvakas in total there are 1028 suktams made up of 10552 mantras. A suktam is a collection of mantras on a particular subject. Originally there were 21 branches of this veda, but now only to i.e.:- Bhashkala and Sakala are in existing. The sub texts of this veda are Brahmanas ( procedural instructions) - Kaushitaki, Sangrayana and Aithareya Aranyakas - Kaushitaki and Aithareya Upanishads - Kaushitaki and Aithareya Gruhya sutra - Asvalayana Yajurveda There are two schools of yajurveda. The shukla yajurveda and the krishna yajurveda. The main difference is that in shukla yajurveda we find mantras alone whereas krishna yajurveda is a mix of mantras and the relevant brahmana bhaga also. Yajurveda consists mainly of procedural mantras used in yajnas and it is in prose. The shukla yajurveda has got two main branches as of today. 1. Vajasaneyi madhyandiniya mainly found in north india 2. Kanva mostly found in Tamil Nadu. Vajasaneyi samhita consists of 303 anuvakas made up of 1975 kandikas classifiec into 40 chapters. Kanva samhita againa has got 40 chapters divided into 328 anuvakas comprising of 2086 kandikas. 1 The krishna yajurveda is made up of 7 kandas divided into 44 prasnas. There are 651 anuvakas made up of 2198 panchashatis (group of fifty words). -

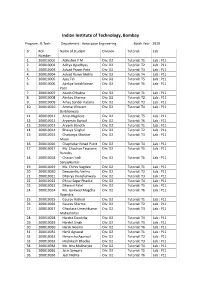

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Vaishvanara Vidya.Pdf

VVAAIISSHHVVAANNAARRAA VVIIDDYYAA by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Publishers’ Note 3 I. The Panchagni Vidya 4 The Course Of The Soul After Death 5 II. Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 26 The Heaven As The Head Of The Universal Self 28 The Sun As The Eye Of The Universal Self 29 Air As The Breath Of The Universal Self 30 Space As The Body Of The Universal Self 30 Water As The Lower Belly Of The Universal Self 31 The Earth As The Feet Of The Universal Self 31 III. The Self As The Universal Whole 32 Prana 35 Vyana 35 Apana 36 Samana 36 Udana 36 The Need For Knowledge Is Stressed 37 IV. Conclusion 39 Vaishvanara Vidya Vidya by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Vaishvanara Vidya is the famous doctrine of the Cosmic Meditation described in the Fifth Chapter of the Chhandogya Upanishad. It is proceeded by an enunciation of another process of meditation known as the Panchagni Vidya. Though the two sections form independent themes and one can be studied and practised without reference to the other, it is in fact held by exponents of the Upanishads that the Vaishvanara Vidya is the panacea prescribed for the ills of life consequent upon the transmigratory process to which individuals are subject, a theme which is the central point that issues from a consideration of the Panchagni Vidya. This work consists of the lectures delivered by the author on this subject, and herein are reproduced these expositions dilating upon the two doctrines mentioned. -

Balabodha Sangraham

बालबोध सङ्ग्रहः - १ BALABODHA SANGRAHA - 1 A Non-detailed Text book for Vedic Students Compiled with blessings and under instructions and guidance of Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 69th Peethadhipathi and Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Sankara Vijayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 70th Peethadhipathi of Moolamnaya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Offered with devotion and humility by Sri Atma Bodha Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Kumbakonam Swamiji) Disciple of Pujyasri Kuvalayananda Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Tambudu Swamiji) Translation from Tamil by P.R.Kannan, Navi Mumbai Page 1 of 86 Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham ॥ श्रीमहागणपतये नमः ॥ ॥ श्री गु셁भ्यो नमः ॥ INTRODUCTION जगत्कामकलाकारं नािभस्थानं भुवः परम् । पदपस्य कामाक्षयाः महापीठमुपास्महे ॥ सदाििवसमारमभां िंकराचाययमध्यमाम् । ऄस्मदाचाययपययनतां वनदे गु셁परमपराम् ॥ We worship the Mahapitha of Devi Kamakshi‟s lotus feet, the originator of „Kamakala‟ in the world, the supreme navel-spot of the earth. We worship the Guru tradition, starting from Sadasiva, having Sankaracharya in the middle and coming down upto our present Acharya. This book is being published for use of students who join Veda Pathasala for the first year of Vedic studies and specially for those students who are between 7 and 12 years of age. This book is similar to the Non-detailed text books taught in school curriculum. We wish that Veda teachers should teach this book to their Veda students on Anadhyayana days (days on which Vedic teaching is prohibited) or according to their convenience and motivate the students. -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

The Spread of Sanskrit* (Published In: from Turfan to Ajanta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serveur académique lausannois Spread of Sanskrit 1 Johannes Bronkhorst Section de langues et civilisations orientales Université de Lausanne Anthropole CH-1009 Lausanne The spread of Sanskrit* (published in: From Turfan to Ajanta. Festschrift for Dieter Schlingloff on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday. Ed. Eli Franco and Monika Zin. Lumbini International Research Institute. 2010. Vol. 1. Pp. 117-139.) A recent publication — Nicholas Ostler’s Empires of the Word (2005) — presents itself in its subtitle as A Language History of the World. Understandably, it deals extensively with what it calls “world languages”, languages which play or have played important roles in world history. An introductory chapter addresses, already in its title, the question “what it takes to be a world language”. The title also provides a provisional answer, viz. “you never can tell”, but the discussion goes beyond mere despair. It opposes the “pernicious belief” which finds expression in a quote from J. R. Firth, a leading British linguist of the mid-twentieth century (p. 20): “World powers make world languages [...] Men who have strong feelings directed towards the world and its affairs have done most. What the humble prophets of linguistic unity would have done without Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit and English, it it difficult to imagine. Statesmen, soldiers, sailors, and missionaries, men of action, men of strong feelings have made world languages. They are built on blood, money, sinews, and suffering in the pursuit of power.” Ostler is of the opinion that this belief does not stand up to criticism: “As soon as the careers of languages are seriously studied — even the ‘Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit and English’ that Firth explicitly mentions as examples — it becomes clear that this self-indulgently tough-minded view is no guide at all to what really makes a language capable of spreading.” He continues on the following page (p. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

Downloaded License

philological encounters 6 (2021) 15–42 brill.com/phen Vision, Worship, and the Transmutation of the Vedas into Sacred Scripture. The Publication of Bhagavān Vedaḥ in 1970 Borayin Larios | orcid: 0000-0001-7237-9089 Institut für Südasien-, Tibet- und Buddhismuskunde, Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract This article discusses the first Indian compilation of the four Vedic Saṃhitās into a printed book in the year 1971 entitled “Bhagavān Vedaḥ.” This endeavor was the life’s mission of an udāsīn ascetic called Guru Gaṅgeśvarānand Mahārāj (1881–1992) who in the year 1968 founded the “Gaṅgeśvar Caturved Sansthān” in Bombay and appointed one of his main disciples, Svāmī Ānand Bhāskarānand, to oversee the publication of the book. His main motivation was to have a physical representation of the Vedas for Hindus to be able to have the darśana (auspicious sight) of the Vedas and wor- ship them in book form. This contribution explores the institutions and individuals involved in the editorial work and its dissemination, and zooms into the processes that allowed for the transition from orality to print culture, and ultimately what it means when the Vedas are materialized into “the book of the Hindus.” Keywords Vedas – bibliolatry – materiality – modern Hinduism – darśana – holy book … “Hey Amritasya Putra—O sons of the Immortal. Bhagwan Ved has come to give you peace. Bhagwan Ved brings together all Indians and spreads the message of Brotherhood. Gayatri Maata is there in every state of India. This day is indeed very auspicious for India but © Borayin Larios, 2021 | doi:10.1163/24519197-bja10016 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license.